Xi's military purge: Why removing generals makes China both weaker and more dangerous

The decimation of China's Central Military Commission has destroyed institutional knowledge and created a culture of fear. But a wounded military is not necessarily a less threatening one—especially for Taiwan.

🎧 Listen to this article

The Last Man Standing

In January 2026, General Zhang Youxia became the latest senior figure to fall in Xi Jinping’s accelerating purge of China’s military elite. Zhang was not some peripheral figure. He was second only to Xi in the military hierarchy, a childhood friend whose father fought alongside Xi’s father in the revolution. If Zhang can be investigated for “grave violations of discipline and the law,” no one is safe.

The Central Military Commission, China’s highest military command body, now has only one of its original six members intact besides Xi himself. The purge has consumed at least 17 generals since 2023, including eight former top commission members. This is not routine housecleaning. This is the systematic decapitation of an entire military leadership class.

The question haunting defense planners from Washington to Taipei is whether this upheaval strengthens or weakens China’s capacity to act on Taiwan. The answer is both—and the timing matters enormously.

The Paradox of Purification

Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign operates on a theory that sounds compelling: remove the corrupt, install the loyal, and military effectiveness will follow like water flowing downhill. The official PLA Daily editorial announcing Zhang’s investigation accused him of having “seriously trampled on and undermined the system of ultimate responsibility resting with the CMC chairman.” Translation: disloyalty to Xi is now indistinguishable from corruption.

This conflation reveals something important. The purges are not primarily about corruption at all. They are about control.

Consider the pattern. The Rocket Force—China’s strategic missile command and the service most critical to any Taiwan operation—has been particularly devastated. Former commanders, procurement officials, and senior officers have been swept away in waves. The same pattern repeats across the navy, air force, and ground forces. What unites these purged officers is not necessarily that they stole more than others. It is that they possessed independent power bases, institutional knowledge, and the capacity for autonomous action.

The logic mirrors what scholars call “coup-proofing”—the practice by which authoritarian leaders deliberately weaken their own militaries to prevent being overthrown. Saddam Hussein did it. Stalin did it. The practice has a consistent outcome: short-term political survival purchased at the cost of long-term military effectiveness.

But Xi’s situation contains a twist. He genuinely believes the purges will improve military capability, not just secure his power. The corruption was real. Procurement fraud diverted billions. Readiness reports were falsified. Officers bought promotions. In this telling, the purges surface hidden problems and create space for genuine reform.

Both interpretations can be true simultaneously. That is what makes the situation so dangerous.

What Gets Lost When Generals Disappear

Military organizations run on tacit knowledge—the accumulated wisdom that exists in experienced heads rather than written manuals. How to coordinate a complex amphibious operation. Which subordinates can be trusted with initiative. Where the real bottlenecks hide in logistics chains. This knowledge cannot be downloaded from a database or taught in a classroom. It develops over decades of exercises, failures, and institutional memory.

The purges are destroying this knowledge base at precisely the moment China needs it most.

The Pentagon’s 2024 report notes that corruption investigations “may be raising questions among leadership about force readiness.” This is diplomatic understatement. When the PLA’s entire senior leadership watches colleagues disappear for unspecified “discipline violations,” the rational response is paralysis. No officer wants to make a decision that might later be characterized as corrupt or disloyal. The safest course is to do nothing bold, approve nothing risky, and wait for explicit orders from above.

This creates a devastating feedback loop. Xi centralizes authority because he distrusts subordinates. Subordinates become passive because independent action invites investigation. Passivity forces Xi to micromanage more. The system becomes increasingly brittle.

For a Taiwan operation—which would require the most complex joint military action in modern Chinese history—this brittleness could prove fatal. Amphibious assaults demand rapid adaptation to changing circumstances. Commanders must exercise initiative when communications fail or plans go wrong. A military culture that punishes initiative cannot execute such operations effectively.

The U.S. Department of Defense assessment acknowledges this tension, noting the purges may set the stage for longer-term improvements while creating immediate readiness concerns. The question is whether “longer-term” arrives before 2027—the date by which Xi has reportedly directed the PLA to be prepared to invade Taiwan.

The 2027 Problem

U.S. intelligence assessments consistently point to 2027 as Xi’s target date for Taiwan readiness. The Pentagon’s 2024 report confirms the PLA continues making “steady progress toward its 2027 goals, whereby the PLA must be able to achieve ‘strategic decisive victory’ over Taiwan.”

But what does “readiness” mean for a military undergoing leadership decapitation?

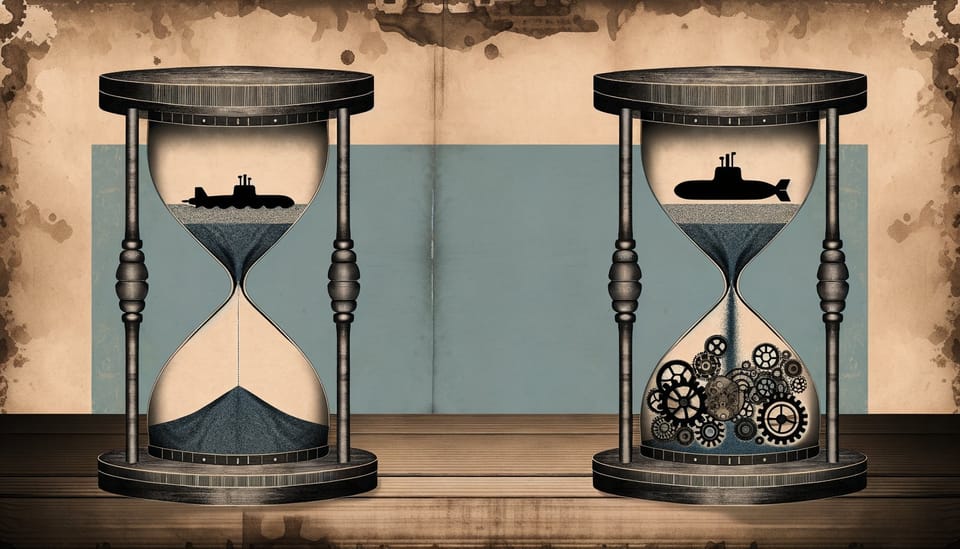

The purges create a metabolic mismatch. Political cycles move fast—investigations can remove a general in weeks. Weapons development moves slowly—a new missile system takes a decade. Leadership development moves slowest of all—producing a competent theater commander requires 25-30 years of progressive experience.

Xi cannot purge his way to competent leadership by 2027. The officers who will command any Taiwan operation are already in uniform. Either they have the experience and judgment to succeed, or they don’t. Removing their superiors doesn’t make them better commanders. It removes their mentors and institutional support.

The Rocket Force illustrates this vividly. The PLARF’s integration into Eastern Theater Command operations requires seamless coordination between missile, naval, and air forces. Such coordination depends on relationships, trust, and shared operational concepts developed over years of joint exercises. When senior leaders disappear, these networks fracture. Rebuilding them takes time China may not have.

Taiwan’s 2025 National Defense Report acknowledges PLA modernization while emphasizing the need for “multi-domain denial, resilient defense” capabilities. Taipei understands that a brittle adversary is not necessarily a less dangerous one. A military that cannot adapt may simply escalate faster when initial plans fail.

The Stalin Parallel and Its Limits

Historical analogies illuminate but also mislead. The comparison to Stalin’s purge of the Red Army in 1937-38 is irresistible—and instructive about both parallels and differences.

Stalin eliminated approximately 35,000 officers, including three of five marshals and 13 of 15 army commanders. When Germany invaded in 1941, the Red Army’s initial performance was catastrophic. Inexperienced commanders made devastating mistakes. The Soviet Union survived only through massive territorial depth, brutal sacrifice, and eventual recovery of professional competence.

China lacks the Soviet Union’s strategic depth. Taiwan is 100 miles away. There is no space to trade for time, no vast hinterland to absorb initial failures. If the first wave of a Taiwan operation fails, there may not be a second chance.

But the parallel has limits. Stalin’s purges targeted ideological enemies and imagined conspiracies. Xi’s purges target corruption and disloyalty—categories that, however politically convenient, correspond to real problems. The PLA did have a corruption crisis. Procurement fraud was systematic. The question is whether the cure proves worse than the disease.

The more apt comparison may be to Iran after the 1979 revolution, when the new regime purged the Shah’s officer corps for political unreliability. The Iranian military performed poorly in the early years of the Iran-Iraq war, suffering defeats that a professional force would have avoided. Recovery took nearly a decade and required the regime to quietly rehabilitate purged expertise.

Xi does not have a decade.

The Loyalty-Competence Trade-off

Every authoritarian leader faces the same dilemma: competent generals can win wars but might also stage coups. Loyal generals won’t overthrow you but might lose battles. The optimal solution is competent loyalty, but this combination is rare and hard to verify.

Purges create adverse selection. Officers who survive demonstrate one skill above all: the ability to avoid investigation. This skill correlates weakly with battlefield competence. The generals who rise in a purge environment are those who took no risks, made no enemies, and left no paper trails. These are not the qualities that win wars.

The investigation of Zhang Youxia sends a particularly chilling signal. Zhang had impeccable loyalty credentials—a princeling whose family ties to Xi dated to the revolutionary generation. If even he could fall, the message to every officer is clear: no level of loyalty guarantees safety. The only security is Xi’s continued personal favor, which can be withdrawn at any moment for any reason.

This environment selects for sycophancy over competence. Officers tell Xi what he wants to hear rather than what he needs to know. Readiness reports become exercises in political theater rather than honest assessments. The disconnect between reported capability and actual capability widens.

When war comes, this gap becomes lethal.

What Taiwan Sees

From Taipei, the purges present a puzzle. A weakened PLA is obviously preferable to a strong one. But weakness can manifest in dangerous ways.

A military that lacks confidence in its conventional capabilities might rely more heavily on coercion short of war—gray zone operations, economic pressure, cyber attacks. These activities require less joint coordination and carry lower risks of catastrophic failure. The purges might paradoxically increase such pressure even as they reduce the threat of outright invasion.

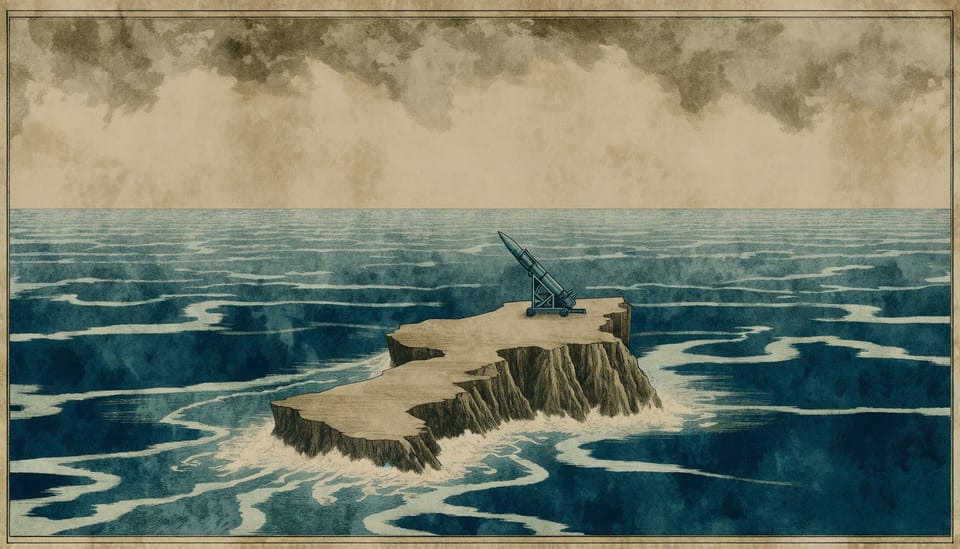

Alternatively, a regime that doubts its military’s ability to execute a complex operation might opt for a simpler, more brutal approach. Massive missile strikes to destroy Taiwan’s defenses before any amphibious operation. Blockade rather than invasion. Escalation to overwhelm rather than maneuver to outthink.

Taiwan’s defense planners must prepare for both a competent adversary and an incompetent one. The latter may actually be more dangerous in some scenarios.

The View from Washington

American strategists face their own dilemma. The purges create opportunities for intelligence collection—disgruntled officers, disrupted communications, organizational chaos. But they also create uncertainty. Who actually commands the PLA now? What are the real lines of authority? How will a purge-traumatized military behave in a crisis?

Deterrence requires that potential adversaries believe aggression will fail. If China’s military is genuinely weakened, this should strengthen deterrence. But deterrence also requires that adversaries make rational calculations. A military culture dominated by fear and sycophancy may not calculate rationally.

The Pentagon’s assessment hedges appropriately, noting both near-term disruption and potential longer-term improvements. This ambiguity reflects genuine uncertainty, not bureaucratic caution. No one outside Xi’s inner circle—and possibly no one inside it—knows how the purges will ultimately affect military capability.

The Path Forward

Three trajectories are possible from here.

Consolidation: Xi completes the purges, installs reliably loyal and reasonably competent successors, and the PLA emerges leaner and more effective. This is Xi’s theory of the case. It requires that loyalty and competence are more compatible than historical evidence suggests, and that institutional knowledge can be rebuilt faster than it was destroyed.

Paralysis: The purges continue indefinitely, creating permanent uncertainty that freezes initiative at all levels. The PLA becomes capable of executing only operations that Xi personally directs in detail. Complex joint operations like a Taiwan invasion become effectively impossible. This outcome favors Taiwan and the United States but may be unstable—Xi might eventually recognize the problem and reverse course.

Miscalculation: A purge-weakened military attempts an operation it cannot execute, either because Xi overestimates its capabilities or because subordinates tell him what he wants to hear. Initial failure leads to escalation as China refuses to accept defeat. This is the nightmare scenario—a war that begins badly and spirals out of control.

The most likely outcome combines elements of all three. Short-term paralysis gives way to partial consolidation, with capability recovering unevenly across different domains. The Rocket Force, despite its purges, may recover faster than the Navy because missile operations are simpler than amphibious assaults. The risk of miscalculation remains elevated throughout the transition.

The Verdict

Do the purges strengthen or destabilize China’s military command? The honest answer is: yes.

They strengthen Xi’s personal control over the military apparatus. They remove officers whose primary loyalty was to their own careers, networks, or institutional prerogatives rather than to Xi personally. They create space for a new generation of leaders whose advancement depends entirely on Xi’s favor.

They destabilize the military’s ability to execute complex operations. They destroy institutional knowledge that cannot be quickly replaced. They create a culture of fear that suppresses honest reporting and independent initiative. They select for sycophancy over competence.

Which effect dominates depends on timing. In the short term—the next two to three years—destabilization dominates. The PLA is less capable today than it was before the purges began. The 2027 deadline looks increasingly unrealistic for any operation more complex than a blockade or missile campaign.

In the longer term, if Xi lives and the purges eventually end, consolidation might prevail. A new generation of Xi loyalists could develop genuine competence over time. The institutional knowledge lost today could be rebuilt over decades.

But Xi is 72 years old. The longer term may not arrive.

Taiwan’s defenders should not take comfort from China’s internal turmoil. A wounded tiger is still dangerous—perhaps more dangerous than a healthy one. The purges make a successful invasion less likely but make the consequences of an attempted invasion more unpredictable.

The safest assumption is the most uncomfortable one: China’s military is simultaneously weakening and becoming more dangerous. Preparing for both requires capabilities that Taiwan and its partners have not yet fully developed. The purges buy time. What matters is how that time is used.

FAQ: Key Questions Answered

Q: Has Xi Jinping purged more generals than any previous Chinese leader? A: The current purge is unprecedented in the post-Mao era. At least 17 generals have been removed since 2023, including eight former Central Military Commission members. The scale approaches—though does not yet match—Mao’s purges during the Cultural Revolution, but those targeted political enemies rather than the professional military.

Q: Why is the Rocket Force particularly affected by the purges? A: The Rocket Force controls China’s strategic missiles and would play a central role in any Taiwan operation. Its procurement budgets are enormous, creating opportunities for corruption. Multiple commanders, deputy commanders, and procurement officials have been removed, disrupting the service’s leadership continuity at a critical moment.

Q: Could the purges delay a Chinese invasion of Taiwan? A: Almost certainly yes, at least in the near term. The 2027 readiness deadline that Xi reportedly set now appears increasingly unrealistic for complex joint operations. However, simpler operations—missile strikes, blockades, gray zone pressure—may remain viable. The purges change what kind of action China can take, not necessarily whether it will act.

Q: What happens to purged Chinese generals? A: Outcomes vary. Some face criminal prosecution and imprisonment for corruption. Others are quietly retired or reassigned to obscure positions. A few have reportedly died under unclear circumstances. The opacity of the process is itself a tool of control—no one knows exactly what fate awaits those who fall from favor.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- Pentagon Annual Report on China 2025 - Authoritative U.S. government assessment of PLA capabilities and leadership changes

- Reuters coverage of CMC purges - Breaking news on senior military official removals

- Caspian Post analysis of PLA purges - Detailed examination of purge patterns and implications

- Andrew Erickson’s compilation of DoD China reports - Historical context for current assessments

- USAWC Press on China’s strategic culture - Academic analysis of Chinese military decision-making

- Taipei Times on 2027 significance - Expert perspectives on China’s military timeline

- Jamestown Foundation on late Stalinism parallels - Historical comparison of authoritarian purge patterns