Xi's military purge: Weakened invasion force or tighter grip on the trigger?

China has removed at least sixty senior military officers since 2023 in its biggest purge since Mao. The campaign has gutted the Rocket Force and frozen defense procurement—yet PLA exercises around Taiwan grow more sophisticated. The purge reveals Xi's priorities: he fears disloyalty more than...

🎧 Listen to this article

The Scalpel and the Sword

When China’s Central Military Commission expelled He Weidong in October 2024, it reduced the body that commands the world’s largest military to an effective membership of two: Xi Jinping and his anti-corruption enforcer, Zhang Shengmin. The math invites alarm. A seven-member war council shrunk to a dyad looks less like streamlining than amputation. Yet the question consuming intelligence analysts from Langley to Taipei—does this purge weaken China’s invasion capacity or strengthen Xi’s grip on the trigger?—may be asking the wrong thing. The purge does both, simultaneously, and the tension between those outcomes is the real story.

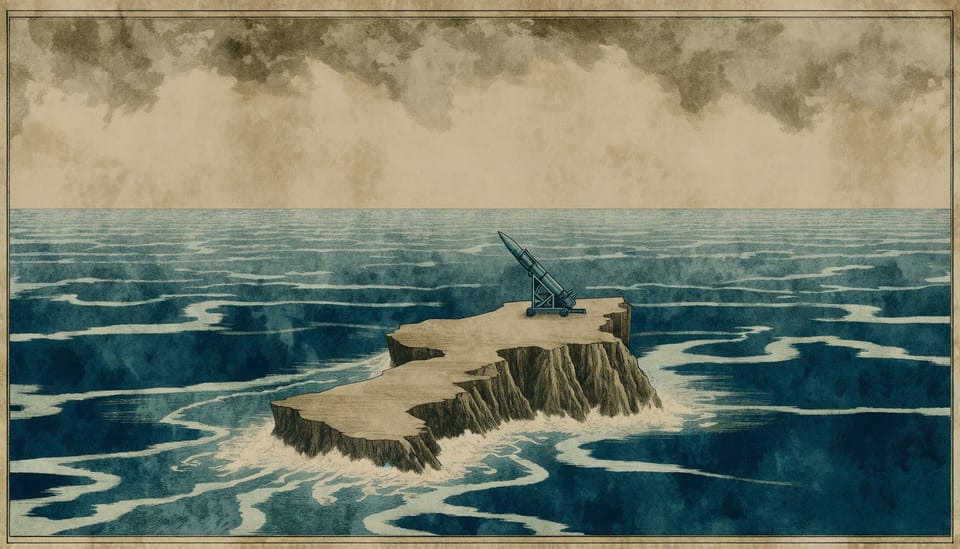

Since 2023, at least sixty senior military officers and defense-industry executives have been removed from their posts, according to the Pentagon’s annual China Military Power Report. Bloomberg called it “China’s biggest purge of military leaders since Mao.” The Rocket Force—China’s nuclear and conventional missile command—has been gutted. Its former commander, Li Yuchao, vanished from public view. Procurement pipelines have seized. Revenues at China’s leading military firms fell 10% in 2024 as anti-corruption investigations froze contracts. And yet the People’s Liberation Army continues to conduct increasingly sophisticated exercises around Taiwan, testing what the Pentagon describes as “essential components of Taiwan invasion options.”

The paradox is not a contradiction. It is a feature.

What the Purge Actually Is

The official narrative frames these removals as anti-corruption enforcement—rooting out officers who sold promotions, skimmed procurement contracts, or otherwise violated “discipline and law.” This explanation is both true and insufficient. Corruption in the PLA is endemic and documented. The Rocket Force scandal reportedly involved defective fuel and falsified maintenance records—problems with potentially catastrophic implications for missile reliability. But anti-corruption campaigns in China are never merely about corruption. They are instruments of political consolidation.

Xi Jinping learned this in his bones. His father, Xi Zhongxun, was purged during the Cultural Revolution. The family home was ransacked. His sister died in the chaos. The lesson Xi absorbed was not that purges are wrong but that survival requires being the one who purges rather than the one purged. His 2012 ascent to power launched an anti-corruption drive that has now ensnared over a million officials across the party-state apparatus. The military’s turn came later, but the logic is identical: loyalty is demonstrated through vulnerability to investigation, and the only safe position is proximity to the leader.

The current wave differs in targeting operational commands rather than administrative posts. Previous purges focused on the General Political Department and logistics networks—important but not combat-critical. The Rocket Force is different. It controls China’s nuclear deterrent and the conventional missiles that would prosecute any Taiwan operation. Removing its leadership signals either profound dysfunction or profound distrust. Probably both.

The pattern suggests Xi is treating a physics problem as a moral failing. Defective missile fuel is an engineering and quality-control issue requiring technical remediation. Instead, it has been addressed through human sacrifice—the ritual expulsion of commanders who may or may not have known about the problems but who certainly failed to prevent them. This approach satisfies the political requirement for accountability while doing nothing to fix the underlying technical failures. The scapegoat mechanism, as René Girard might recognize, restores social cohesion by concentrating blame on individuals. It does not restore missile reliability.

The Command Architecture Under Stress

Xi’s consolidation has transformed the Central Military Commission from a collective leadership body into something resembling an imperial inner court. The CMC theoretically exercises “ultimate command authority over the armed forces,” but that authority now flows through an unprecedentedly narrow channel. Zhang Shengmin, the surviving vice chairman, is not a warfighter. His career has been in political work and anti-corruption enforcement. His father served alongside Xi’s father in the revolutionary generation, creating a bond of hereditary loyalty that Xi apparently values above operational experience.

This matters because command and control in a Taiwan scenario would require rapid, decentralized decision-making under conditions of uncertainty and electronic warfare. The PLA has invested heavily in joint operations doctrine, creating theater commands designed to integrate air, naval, ground, and missile forces. But doctrine on paper and execution under fire are different things. The purge has disrupted the human networks that make joint operations possible.

Consider the incentive structure facing a PLA officer today. Initiative carries risk. Reporting problems up the chain invites scrutiny of why you knew about problems and failed to solve them. The safest career strategy is to avoid decisions that could later be characterized as mistakes—which means avoiding decisions altogether. Organizational silence becomes rational. The fear of negative feedback suppresses the flow of critical information about equipment quality, training deficiencies, and operational readiness. What reaches the top is filtered through layers of self-protective ambiguity.

This dynamic compounds the challenge of invasion planning. Amphibious operations are among the most complex military undertakings. They require precise coordination across services, accurate intelligence about beach conditions and defender dispositions, and the ability to adapt when initial plans contact reality. The Normandy invasion succeeded partly because Eisenhower empowered subordinate commanders to make tactical decisions. A PLA where officers fear initiative more than the enemy faces a structural disadvantage that no amount of hardware can overcome.

The Capability Question

Yet hardware matters too, and here the picture is more ambiguous. Taiwan’s 2025 National Defense Report notes that “China’s persistent military activities near Taiwan, combined with new capabilities such as large amphibious assault ships and mobile piers, have enhanced China’s capacity to blockade or launch an invasion of Taiwan with little advance warning.” The Type 075 amphibious assault ships continue to enter service. The civilian maritime militia—fishing vessels that can be mobilized for logistics and reconnaissance—practices invasion scenarios regularly. Satellite imagery shows continued construction of military infrastructure opposite Taiwan.

The 2027 timeline looms over all assessments. U.S. intelligence has reported that Xi instructed the PLA to be ready by 2027 to conduct a successful invasion—a capability deadline, not an invasion date, but one that focuses minds in Taipei and Washington. Whether the purge delays this timeline is the question that matters most for near-term planning.

The evidence points in contradictory directions. On one hand, the Rocket Force’s dysfunction is real. If conventional missiles cannot be trusted to perform as designed, the opening salvos of any Taiwan operation become uncertain. The defense industry’s revenue decline suggests procurement delays that ripple through production schedules. Officers removed from command take institutional knowledge with them; their replacements require time to establish relationships and understand their units’ actual (as opposed to reported) capabilities.

On the other hand, the PLA’s exercises have grown more sophisticated, not less. The Pentagon’s 2024 report documents strikes on sea and land targets, blockade rehearsals, and joint operations that demonstrate genuine capability development. The purge may have disrupted specific units while leaving broader modernization on track. Or the exercises may be Potemkin performances—impressive on satellite imagery but hollow in execution. Outside observers cannot know which interpretation is correct, and that uncertainty is itself strategically significant.

The Loyalty-Competence Trade-off

Every authoritarian leader faces a fundamental tension: the officers most capable of winning wars are also most capable of mounting coups. Xi has chosen to prioritize loyalty over competence more explicitly than his predecessors. The question is whether he has miscalculated the trade-off.

The historical record offers cautionary tales. Stalin’s purge of the Red Army officer corps in 1937-38 removed experienced commanders and contributed to the catastrophic early defeats of 1941. Yet the Soviet Union ultimately won. Saddam Hussein’s coup-proofing of the Iraqi military through parallel command structures and tribal loyalty networks produced an army that collapsed twice against American forces. The difference may be that Stalin had strategic depth and Western allies; Saddam had neither.

China’s situation resembles neither case precisely. The PLA has not experienced the wholesale decapitation Stalin inflicted. And China’s strategic depth against Taiwan is measured in hours of flight time, not thousands of kilometers. The relevant comparison may be whether the purge has degraded capability below the threshold required for successful invasion—a threshold that depends on Taiwan’s defense preparations, American intervention decisions, and operational factors that cannot be known in advance.

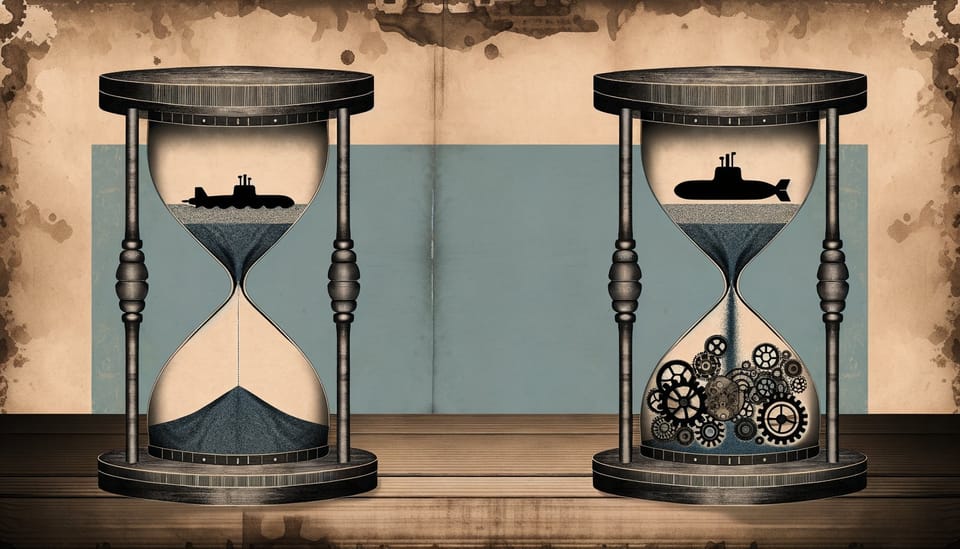

What can be assessed is revealed preference. Xi’s actions suggest he believes the loyalty problem is more urgent than the competence problem. He is willing to accept near-term operational disruption to ensure that the officers who remain would execute his orders without hesitation. This implies either confidence that the disruption is manageable or acceptance that invasion is not imminent. The latter interpretation aligns with the 2027 timeline as a capability milestone rather than an action date.

The Feedback Loop Problem

The purge creates information pathologies that may be invisible to Xi himself. When officers fear that reporting problems will be interpreted as disloyalty, they stop reporting problems. When defense contractors fear that admitting quality issues will trigger investigations, they falsify records. The result is a system that generates increasingly optimistic assessments of its own capabilities while actual capabilities stagnate or decline.

This dynamic has a name in organizational theory: the success theater. Everyone performs competence for their superiors, who perform competence for their superiors, until the performance reaches the top and is mistaken for reality. The danger is not that Xi will order an invasion knowing the PLA is unready. The danger is that he will order an invasion believing the PLA is ready because everyone has told him so.

The problem is structural, not personal. Even if Xi wanted accurate information, the incentive system he has created works against it. The officers who survive purges are those skilled at avoiding blame, not those skilled at winning battles. Promotion selects for political survival rather than operational excellence. Over time, this produces a leadership cadre whose primary competency is navigating the internal political environment rather than the external military one.

Taiwan’s decision to extend conscription from four months to one year may reflect this assessment. If Taipei perceives declining PLA coherence, extending military service makes sense as a hedge against windows of vulnerability. The signal is ambiguous—it could indicate confidence or fear—but it suggests Taiwan’s planners see something in the purge worth responding to.

What the West Gets Wrong

Western analysts tend to interpret the purge through one of two lenses: weakness or strength. The weakness narrative emphasizes disruption, dysfunction, and degraded capability. The strength narrative emphasizes consolidation, control, and enhanced decision-making speed. Both capture part of the picture. Neither captures the whole.

The more accurate frame is that Xi is optimizing for a different objective function than Western analysts assume. He is not maximizing invasion capability in the abstract. He is maximizing invasion capability conditional on absolute political control. These are not the same thing. The difference explains why actions that look irrational from a pure military-effectiveness standpoint make sense from Xi’s perspective.

This reframing has implications for deterrence. If Xi’s primary concern is internal control, then external signals about military consequences may be less effective than assumed. He may be willing to accept higher military risk to avoid political risk. Conversely, signals that threaten his political control—support for internal dissent, information operations targeting elite cohesion—may be more effective than traditional military deterrence.

The intelligence challenge is severe. Assessments of PLA degradation create a paradox: the more Western analysts publicly discuss Chinese weakness, the more pressure Xi faces to demonstrate strength through exercises or gray-zone escalation. The observer effect applies to strategic analysis. Publishing conclusions about capability gaps may close those gaps by forcing compensatory action.

The Path from Here

Three scenarios deserve consideration. In the first, the purge is a temporary disruption that gives way to renewed capability once loyal officers consolidate control. The 2027 timeline slips modestly but remains achievable. Xi emerges with a military that is both capable and controllable—the best of both worlds.

In the second scenario, the purge triggers a cascade failure. Quality problems in the Rocket Force prove symptomatic of deeper dysfunction across the defense industrial base. Officers optimized for political survival prove unable to execute complex joint operations. The capability gap widens, and Xi faces a choice between accepting indefinite delay or launching an operation with forces he knows are inadequate.

In the third scenario, the purge produces a military that is capable enough for coercion but not invasion. Blockades, missile strikes, and gray-zone operations remain viable. Full amphibious assault does not. Xi adjusts his strategy accordingly, pursuing Taiwan’s subordination through pressure rather than conquest. This outcome satisfies neither hawks who want reunification nor doves who want stability, but it may be the most likely.

The honest assessment is uncertainty. The purge has disrupted PLA command structures in ways that degrade near-term invasion readiness. It has also consolidated Xi’s authority in ways that could accelerate decision-making if he chooses to act. Whether the net effect favors Taiwan’s security depends on factors that cannot be observed from outside: the actual state of missile reliability, the true morale of PLA officers, and Xi’s private assessment of acceptable risk.

What can be said with confidence is that the purge reveals Xi’s priorities. He fears disloyalty more than he fears operational disruption. He trusts political control more than military expertise. He is willing to sacrifice capability for certainty. These revealed preferences tell us something important about how he would approach a decision to use force—and about the limits of external deterrence in shaping that decision.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Has China’s military purge delayed the 2027 Taiwan invasion timeline? A: The purge has disrupted Rocket Force command structures and defense procurement, creating near-term capability gaps. However, 2027 was always a readiness milestone rather than an invasion date. The purge likely introduces months of delay in specific capabilities while leaving broader modernization largely on track.

Q: Why did Xi Jinping purge the Rocket Force specifically? A: The Rocket Force controls both nuclear and conventional missiles critical to any Taiwan operation. Reports of defective fuel and falsified maintenance records suggested quality-control failures with potentially catastrophic implications. Xi’s response treated these technical problems as loyalty failures, removing commanders to restore political control rather than addressing underlying engineering issues.

Q: Does the purge make China more or less likely to invade Taiwan? A: Both interpretations have merit. The purge degrades operational capability in the near term, reducing invasion feasibility. But it also consolidates Xi’s personal authority over military decisions, potentially enabling faster action if he chooses. The net effect depends on whether Xi prioritizes capability or control—and his actions suggest he prioritizes control.

Q: How does the PLA purge compare to Stalin’s Red Army purges? A: Stalin’s 1937-38 purges removed far more officers proportionally and contributed to catastrophic defeats in 1941. Xi’s purge is more targeted, focusing on specific commands rather than wholesale decapitation. However, both purges share the dynamic of prioritizing political loyalty over military competence, with uncertain long-term consequences for operational effectiveness.

The Sword Remains Sheathed

The Central Military Commission now fits around a small table. Xi Jinping sits at its head, flanked by an anti-corruption enforcer whose career has been spent investigating soldiers rather than leading them. Somewhere in this arrangement lies China’s capacity to make war on Taiwan—or the incapacity that deters it. The purge has not answered the question of whether China can successfully invade. It has revealed that Xi considers the question secondary to another one: whether the military that invades will be his.

That revelation should trouble everyone. A leader who fears his own generals may hesitate to use them. Or he may use them precisely because he finally trusts them—not to win, but to obey. The sword remains sheathed. The hand on its hilt has never gripped tighter.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- Pentagon China Military Power Report 2024 - Comprehensive U.S. government assessment of PLA capabilities and purge impacts

- Taiwan National Defense Report 2025 - Taipei’s official assessment of Chinese military threats and capabilities

- Wall Street Journal investigation on Xi’s military overhaul - Detailed reporting on the scope and scale of leadership removals

- Columbia University analysis of Chinese command and control - Expert assessment of PLA decision-making structures in Taiwan scenarios

- U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Taiwan chapter - Congressional analysis of invasion timelines and capability assessments

- Air University analysis of PLA command and control - Military academic perspective on operational implications