Xi's military purge: war preparation or proof that China can't fight?

The largest removal of Chinese generals since Mao reveals a military hollowed by corruption while racing toward a 2027 Taiwan deadline. Xi Jinping is simultaneously cleaning house and discovering the house was far dirtier than he knew.

🎧 Listen to this article

The Generals Who Vanished

Between July and December 2023, at least fifteen high-ranking Chinese military officers and defense industry executives disappeared from public view. No trials. No announcements. Just absence. By mid-2025, the count exceeded one hundred generals—the largest purge of military leaders since Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution. The question consuming Western intelligence agencies is deceptively simple: does this represent preparation for war, or proof that war has become impossible?

The answer, uncomfortable as it may be, is both.

Xi Jinping is simultaneously cleaning house for a potential Taiwan operation and discovering that the house was far dirtier than he knew. The purge reveals a military hollowed by corruption while attempting to remedy that hollowing before a self-imposed 2027 deadline. This is not a contradiction. It is the defining tension of Chinese military power in the 2020s.

What the Purge Actually Shows

The conventional reading splits neatly into two camps. Hawks argue Xi is removing obstacles to invasion, installing loyalists who will execute orders without hesitation. Doves counter that you don’t decapitate your rocket force leadership eighteen months before an amphibious assault. Both interpretations contain truth. Neither captures the full picture.

Start with the targets. The Rocket Force—China’s nuclear and conventional missile command—lost its commander Li Yuchao, his successor Zhou Yaning, and Chief of Staff Li Chuanguang in rapid succession. The Equipment Development Department, responsible for procurement and weapons systems, was gutted. Two consecutive defense ministers, Wei Fenghe and Li Shangfu, were expelled from the Communist Party entirely. These are not peripheral figures. They controlled the weapons Xi would need for any Taiwan operation.

The charges, where specified, center on corruption. But corruption in Chinese officialese covers multitudes: actual graft, political disloyalty, factional allegiance, or simply being associated with someone who fell. What matters is the pattern. The purge concentrated in precisely the institutions most critical to military modernization—and most opaque to outside oversight.

U.S. intelligence reports paint an alarming picture of what investigators found. According to Reuters, missiles contained water instead of fuel. Silo lids didn’t fit. Procurement contracts enriched officials while delivering substandard equipment. The rot wasn’t cosmetic. It was structural.

This explains the purge’s ferocity. Xi didn’t merely suspect disloyalty; he discovered that the military he had spent a decade building existed partly on paper. The gap between reported capabilities and actual readiness may have shocked even him.

The 2027 Problem

The timeline matters enormously. U.S. intelligence assessments consistently cite 2027 as the year Xi ordered the PLA to be capable of taking Taiwan by force. This date carries symbolic weight—the centennial of the People’s Liberation Army’s founding. It also reflects hard military logic: demographic decline, economic headwinds, and Taiwan’s accelerating defense investments all suggest China’s relative advantage may peak rather than grow.

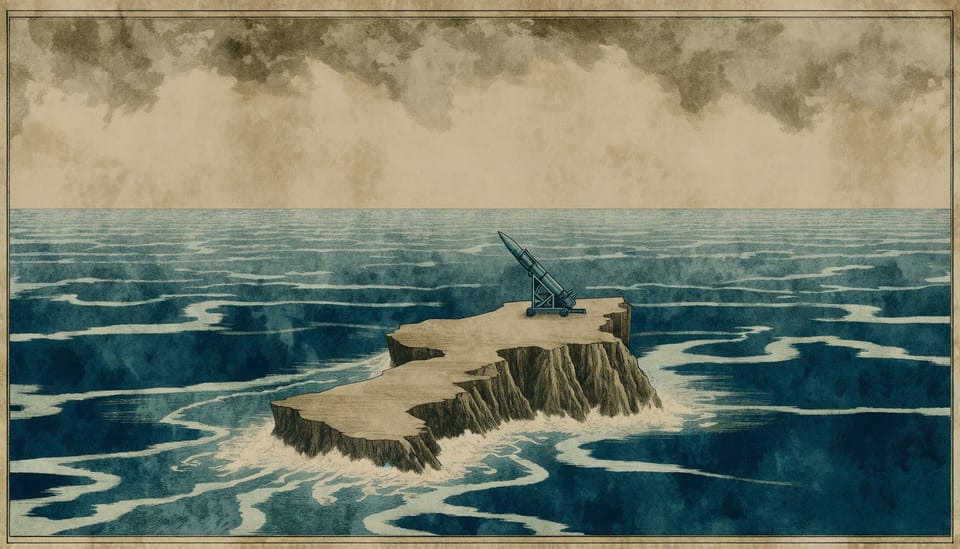

The Pentagon’s 2025 report states bluntly that China expects to fight and win a Taiwan war by 2027. Multiple military options remain in development: amphibious invasion, firepower strikes, maritime blockade, and hybrid coercion campaigns. The buildup continues regardless of the purge.

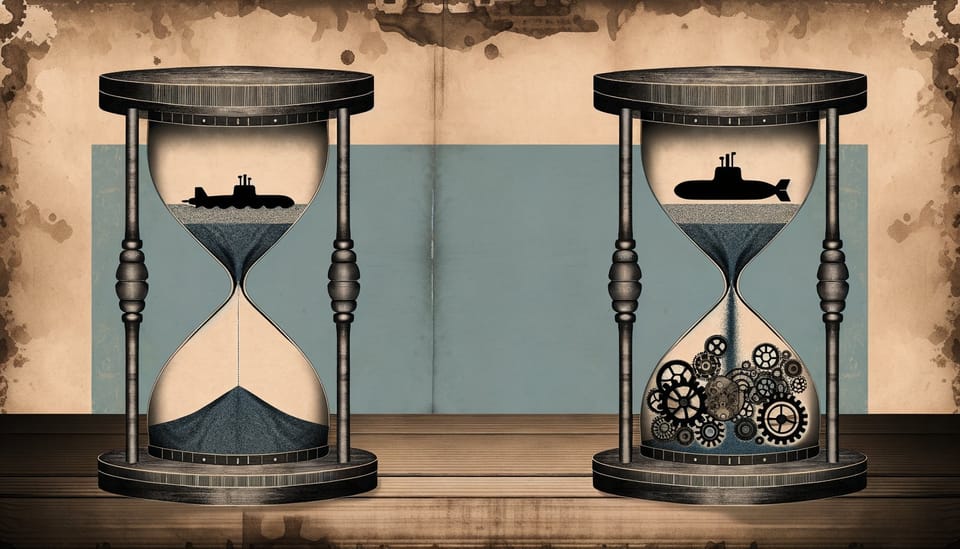

But here lies the paradox. The purge simultaneously advances and undermines the 2027 goal. Removing corrupt officers theoretically improves readiness. Removing experienced commanders definitely damages institutional knowledge. Training suffers when generals fear making decisions. Initiative dies when loyalty becomes the paramount virtue.

Consider the Rocket Force specifically. This organization manages China’s nuclear deterrent and the conventional missiles that would suppress Taiwan’s defenses and deter American intervention. Its leadership has been eviscerated. The Pentagon notes that corruption investigations “may have disrupted the PLA’s progress toward its 2027 goals.” May have is diplomatic understatement.

The Loyalty Trap

Xi Jinping’s biography explains much. During the Cultural Revolution, his father was purged, his family destroyed, his sister died by suicide, and his mother publicly denounced him. He learned early that political fortunes reverse without warning. Even loyalty offers no protection.

This formative trauma produces a specific decision pattern: centralize all major decisions personally, eliminate threats preemptively, tolerate high risk for core objectives. The purge reflects all three tendencies. Xi trusts no one completely. He removes potential rivals before they become actual threats. He accepts short-term military disruption for long-term control.

The Central Military Commission now contains only Xi and one other member, Vice Chairman Zhang Shengmin. Zhang’s background is in political work and anti-corruption enforcement, not combat command. His survival depends on total deference to Xi’s judgment. This is not a structure designed for independent military advice.

The new Defense Minister, Dong Jun, was appointed in December 2023 after his predecessor’s arrest. His career has been in naval operations, not the army-dominated Taiwan planning apparatus. He witnessed two consecutive defense ministers fall to corruption charges. The lesson is unmistakable: avoid exposure, defer constantly, never contradict the chairman.

This creates what organizational theorists call an information pathology. Bad news stops flowing upward. Commanders report what leaders want to hear. The gap between perception and reality widens precisely when accurate assessment matters most.

Corruption as Capability Constraint

Western analysts often treat corruption as a moral failing. In military terms, it functions as a physics problem. Corrupt procurement doesn’t just steal money; it degrades equipment. Corrupt training doesn’t just waste time; it produces soldiers who cannot fight. Corrupt logistics doesn’t just enrich officials; it means ammunition that doesn’t arrive.

The specific allegations against Rocket Force leadership illuminate this dynamic. If missiles genuinely contained water instead of fuel—and multiple intelligence sources confirm variants of this claim—then China’s conventional deterrent against American intervention may be significantly weaker than satellite counts suggest. The number of launchers matters less than the number of functional weapons.

This has profound implications for Taiwan scenarios. Chinese military doctrine emphasizes the “anti-access/area denial” concept: making American intervention so costly that Washington hesitates. That concept depends on missiles that work. If corruption compromised even a fraction of the arsenal, the entire strategic calculation shifts.

The purge acknowledges this problem. But acknowledgment and solution differ. Replacing corrupt generals doesn’t automatically produce functional missiles. Rebuilding institutional trust takes years. Training new leadership requires precisely the experienced officers being removed.

What Taiwan Sees

Taipei watches the purge with complicated emotions. On one hand, evidence of PLA dysfunction provides reassurance. On the other, a leader who discovers his military isn’t ready might delay—or might accelerate before the window closes entirely.

Taiwan’s own preparations have intensified. Reserve mobilization reforms, increased defense spending, and closer coordination with American trainers all signal awareness that time may be short. The annual Han Kuang exercises have grown more realistic. Indigenous defense industries are expanding.

But Taiwan faces its own readiness problems: aging equipment, recruitment challenges, and a political system that struggles to sustain defense consensus. The cross-strait military balance continues shifting toward Beijing despite the purge. Taiwan cannot assume Chinese dysfunction will persist indefinitely.

The purge may actually increase near-term risk in one specific way. If Xi believes his military window is closing—due to corruption exposure, demographic decline, or American buildup—he might calculate that imperfect readiness now beats perfect readiness never. Desperate leaders make dangerous choices.

The International Dimension

American policy assumes deterrence works: that sufficient military presence and alliance coordination will convince Beijing that Taiwan’s conquest costs exceed its value. The purge complicates this assumption in both directions.

If corruption has genuinely degraded PLA capabilities, deterrence may be easier than feared. China might lack the actual ability to execute a successful invasion regardless of political will. This would be good news—if true and if Beijing recognizes it.

But if Xi believes the purge has fixed the problems—or will fix them by 2027—deterrence requires demonstrating that American and allied capabilities have grown proportionally. The Pentagon’s assessment that the U.S. is “increasingly vulnerable” to Chinese military buildup suggests this demonstration is not yet convincing.

Japan’s defense transformation adds another variable. Tokyo’s historic shift toward offensive capabilities and increased defense spending reflects genuine alarm about regional security. This buildup could either deter Chinese adventurism or convince Beijing that delay only worsens its position.

The U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission concluded in 2025 that “we have entered a crucial phase in Beijing’s longstanding efforts to impose sovereignty over Taiwan.” Crucial phase is bureaucratic language for danger zone.

The Readiness Paradox

Military readiness is not a single variable. It encompasses equipment functionality, personnel training, leadership quality, logistics capacity, and institutional cohesion. The purge affects each differently.

Equipment functionality may improve if corrupt procurement is genuinely reformed. But reform takes time, and weapons systems have long development cycles. Missiles designed under corrupt contracts don’t become reliable because the contracting officer was arrested.

Personnel training suffers when officers fear making mistakes. The PLA’s historical weakness has been initiative at lower levels—the ability of junior officers and NCOs to adapt when plans fail. Purges that emphasize loyalty over competence worsen this problem.

Leadership quality presents the sharpest trade-off. Xi is removing experienced commanders and replacing them with loyalists. Loyalty and competence are not mutually exclusive, but they are not identical either. The officers who survive purges are those skilled at political navigation. Political navigation and battlefield command require different talents.

Logistics capacity depends on honest reporting and functional supply chains. Corruption corrodes both. The purge may eventually improve logistics by removing those who falsified reports and skimmed supplies. In the short term, it creates uncertainty about what actually exists in warehouses and depots.

Institutional cohesion—the intangible that makes military organizations function under stress—takes the hardest hit. Trust between officers evaporates when anyone might be the next to disappear. Information stops flowing. Coordination suffers. The very qualities that enable complex operations like amphibious invasion degrade.

What Happens Next

Three scenarios deserve consideration. None is certain. All are possible.

Scenario one: Delayed action. Xi concludes that the purge revealed problems too severe for the 2027 timeline. He extends the deadline, prioritizes rebuilding, and accepts that Taiwan must wait. This is the optimistic case for stability. It requires Xi to acknowledge limits—something his personality and political position make difficult.

Scenario two: Accelerated action. Xi concludes that problems will only worsen with time. American alliances strengthen. Taiwan’s defenses improve. Demographic decline accelerates. He orders action before the window closes entirely, accepting imperfect readiness as better than no opportunity. This is the pessimistic case. It becomes more likely if Xi believes the purge has addressed core problems.

Scenario three: Permanent preparation. The purge becomes a continuous process rather than a discrete event. Xi keeps the military in permanent readiness posture without actual invasion, using the threat to extract concessions and maintain domestic mobilization. This is the muddling-through case. It postpones crisis without resolving it.

The evidence supports none of these definitively. Xi’s intentions remain opaque even to close observers. The purge could be preparation, remediation, or both simultaneously. What we know is that China’s military is undergoing the most significant leadership disruption in decades while maintaining the posture and rhetoric of imminent action.

The Uncomfortable Truth

Western analysts want clarity: either China is preparing to invade Taiwan, or it isn’t. The purge should reveal which. It doesn’t.

What it reveals instead is a military system that was simultaneously more corrupt and more ambitious than previously understood. Xi is attempting to fix the corruption without abandoning the ambition. Whether he can do both remains uncertain. Whether he believes he can do both matters more.

The purge demonstrates that China’s military modernization was partly illusory—a Potemkin buildup where reported capabilities exceeded actual ones. This should provide some reassurance. It also demonstrates that Xi considers Taiwan important enough to risk massive institutional disruption. This should provide alarm.

The safest assumption is the most uncomfortable: China’s military is weaker than it appeared but still dangerous; the purge delays action but doesn’t prevent it; Xi’s timeline has slipped but not his intentions. Taiwan remains in danger. The danger has merely become harder to predict.

Those who want the purge to signal either imminent war or permanent peace will be disappointed. It signals neither. It signals a leader who discovered his tools were flawed and is attempting to repair them before use. The repair may succeed. The use may follow. The uncertainty is the point.

FAQ: Key Questions Answered

Q: Does the purge mean China can’t invade Taiwan by 2027? A: Not necessarily. The purge has disrupted military leadership and revealed capability gaps, but China continues building forces and refining invasion plans. The 2027 deadline may slip, but the underlying intention appears unchanged.

Q: Why did Xi purge the Rocket Force specifically? A: The Rocket Force controls both nuclear deterrence and the conventional missiles critical to any Taiwan operation. Corruption there directly threatened Xi’s most important military capabilities. Intelligence reports of defective missiles and equipment suggest the problems were severe.

Q: Could the purge actually improve China’s military readiness? A: In the long term, possibly. Removing corrupt officers and reforming procurement could eventually produce more capable forces. In the short term, the disruption to leadership, training, and institutional trust likely reduces readiness.

Q: What should Taiwan do in response? A: Taiwan should continue accelerating defense investments while recognizing that Chinese dysfunction may be temporary. The purge provides a window, not permanent safety. Strengthening reserves, stockpiling supplies, and deepening alliance coordination remain essential regardless of PLA internal politics.

The Generals Who Remain

The officers who survived Xi’s purge share one characteristic: they understood what was being asked of them. Loyalty above all. Deference without question. The skills that ensure survival in a purge differ from those that win wars. Xi may have built the military he wanted. Whether it is the military he needs remains to be tested.

That test may come sooner than anyone prefers. Or it may be postponed indefinitely while both sides prepare for a conflict neither can afford. The purge has not clarified China’s intentions. It has clarified the stakes. Whatever Xi decides, he will decide with generals who know their careers—and possibly their lives—depend on telling him what he wants to hear.

That is not a recipe for sound military judgment. It may be the most important consequence of all.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- Pentagon Annual Report on Chinese Military and Security Developments - Primary source for U.S. assessments of PLA capabilities and 2027 timeline

- Reuters coverage of Pentagon corruption findings - Details on equipment defects and procurement failures

- U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Taiwan chapter - Congressional assessment of cross-strait dynamics

- Jamestown Foundation purge documentation - Comprehensive tracking of purged officers and positions

- ISDP analysis of corruption’s military impact - European perspective on systemic corruption effects

- Jamestown Foundation analysis of 2027 goals - Context on PLA centennial timeline significance

- NDU Press “Crossing the Strait” study - Military analysis of invasion scenarios