Xi Jinping's military purge: What the fall of China's top generals reveals

The elimination of nearly the entire senior command structure—including Xi's closest military ally—signals neither war preparation nor regime collapse. It signals both, simultaneously, in ways that make prediction impossible.

🎧 Listen to this article

The Purge That Proves Nothing

Zhang Youxia survived the Cultural Revolution, fought in the Sino-Vietnamese War, and rose to become the second most powerful military figure in China. By January 2026, he was under investigation for “seriously betraying the trust and expectations” of the Communist Party. His fall—alongside Liu Zhenli, the chief of the Joint Staff Department—has eliminated nearly the entire senior command structure Xi Jinping assembled just three years earlier.

Of the seven Central Military Commission members formed in 2022, only Xi himself and Zhang Shengmin remain. Western analysts call this “the total annihilation of the high command.” The question dominating intelligence assessments from Washington to Taipei is deceptively simple: Is Xi purging his generals because he’s preparing for war, or because his regime is fracturing?

The answer is neither. And both.

The Corruption Alibi

The official narrative is tidy. Zhang Youxia and his colleagues “fostered political and corruption problems that undermined the party’s absolute leadership over the military,” according to PLA Daily. The language echoes every anti-corruption campaign since Xi took power in 2012. Corruption is real. The Rocket Force procurement scandals revealed genuine rot—officers taking bribes for missile contracts, defense firms delivering substandard equipment, modernization budgets disappearing into private accounts.

But corruption has always been endemic in the PLA. What changed is Xi’s definition of the crime.

The 2026 revisions to military disciplinary regulations distinguish between peacetime, wartime, and “major non-war military operations”—a category that didn’t exist before. Officers can now be punished for failures of political discipline that would have been unremarkable a decade ago. The standard isn’t whether you stole. It’s whether you demonstrated sufficient loyalty.

Zhang Youxia’s case illuminates the distinction. He was Xi’s closest military ally, trusted enough to appoint his own security chief, retained beyond normal retirement age, treated “almost as an elder brother” by the paramount leader. His battlefield experience in 1979 gave him legitimacy no other serving general possessed. He was also willing to resist Xi’s directives when institutional interests were at stake—a pattern that analysts at Jamestown Foundation identified as increasingly intolerable to a leader who demands total compliance.

The corruption charges are the mechanism. The purpose is something else entirely.

The Loyalty Paradox

Xi Jinping learned his politics during the Cultural Revolution. His father, Xi Zhongxun, was a revolutionary hero who became a purge victim—imprisoned, denounced, his family scattered. The young Xi was branded a “capitalist roader” at nine years old, attacked by Red Guards, reported to authorities by his own mother when he tried to defend her. He spent seven years in rural exile, sleeping in caves, rated “6 out of 10” by fellow laborers.

This biography produces a specific kind of leader. Xi understands that revolutionary credentials offer no protection. He knows that institutional position can evaporate overnight. He believes—with the certainty of someone who nearly died for his father’s sins—that personal loyalty is the only reliable foundation for power.

The problem is that loyalty cannot be measured. It can only be tested.

Purges collapse what physicists might call a superposition of loyalty states. Before the investigation, an officer exists in an indeterminate condition—potentially loyal, potentially treacherous. The purge forces a binary outcome. Survive, and your loyalty is confirmed. Fall, and your betrayal was always latent.

This creates a monitoring problem that would be familiar to any student of authoritarian systems. The more Xi purges, the more he signals uncertainty about who remains loyal. The more he signals uncertainty, the more officers must engage in performative displays of commitment. The demand for active loyalty creates a double bind: silence becomes suspicious, but speaking risks violating vague definitions of political correctness. The system generates the instability it claims to cure.

Zhang Shengmin, the CMC member who oversees military anti-corruption, has survived by understanding this logic. His career pattern shows systematic escalation rather than compromise—he investigates former mentors and colleagues, demonstrates loyalty through visible action rather than rhetoric. He is the instrument of purges, which makes him temporarily indispensable. But “temporarily” is the operative word.

The Readiness Question

The Pentagon’s 2024 China Military Power Report estimates that China spends 40-90% more than its announced defense budget—somewhere between $330 billion and $450 billion annually. That money has produced a navy larger than America’s, a nuclear arsenal expanding faster than any since the Cold War, and a Rocket Force designed to hold U.S. carriers at risk across the Western Pacific.

The purges have disrupted this machinery. Leadership churn in the Eastern Theater Command—the formation responsible for any Taiwan operation—has replaced commanders faster than they can build relationships with subordinates. The Rocket Force, which suffered its own purge wave in 2023-2024, lost institutional memory precisely when it was integrating new missile systems. Officers promoted to fill vacancies lack the tacit knowledge that comes from years of joint exercises and war games.

In the short term, this degrades readiness. Plans developed under one commander must be relearned by his successor. Trust networks that enable rapid decision-making dissolve when participants disappear. The PLA’s shift toward “informatized warfare”—data-driven, AI-enabled, requiring high-speed information flow across joint domains—is fundamentally incompatible with an environment where any communication might be evidence of disloyalty.

But short-term degradation may be the point.

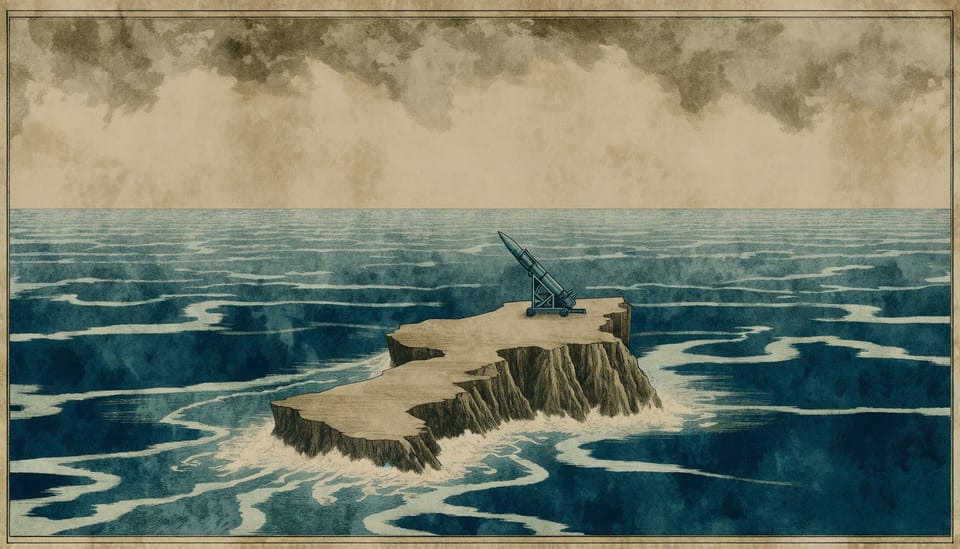

Xi’s 2027 deadline for Taiwan readiness has always been more political than operational. It marks the centenary of the PLA’s founding, a symbolic milestone in the Party’s narrative of national rejuvenation. Missing the deadline carries ideological cost. Attempting a Taiwan operation with commanders Xi doesn’t trust carries existential risk.

The purges buy time by creating a plausible excuse. Western analysts interpret the chaos as evidence that China cannot invade Taiwan soon. This interpretation may be correct. It may also be strategic cover—a way to extend training cycles and consolidate control without appearing to retreat from force thresholds.

The uncertainty is the message.

The Command Psyche

Chinese military doctrine emphasizes what internal documents call “mental fortification”—the psychological preparation of officers for high-stakes conflict. The ideal commander combines technical competence with ideological purity, operational flexibility with absolute obedience to Party directives. These requirements contradict each other.

Mission command, the Western doctrine that enables junior officers to exercise initiative within commander’s intent, requires high trust and tolerance for error. The PLA has studied mission command extensively. It has not adopted it. The risk-averse culture that purges reinforce makes autonomous decision-making professionally suicidal. Better to wait for orders than to act and be wrong.

This creates a force optimized for peacetime display rather than wartime adaptation. Large-scale exercises demonstrate coordination. They do not test what happens when communications fail, when plans collapse, when junior officers must improvise. The officers who might develop such skills are precisely those most likely to be purged for showing insufficient deference.

The parallel to Soviet military dysfunction before 1941 is inexact but instructive. Stalin’s purges eliminated the Red Army’s most capable commanders, replacing them with political loyalists who froze when German forces attacked. The PLA today is not the Red Army of 1941—it is better equipped, better trained, and has not faced a comparable threat. But the institutional logic is similar. Systems that punish initiative produce officers who avoid it.

The Taiwan Calculus

Taiwan’s security establishment watches the purges with careful attention and uncertain conclusions. Analysts note that leadership instability reduces the near-term risk of military action—you don’t launch complex amphibious operations with commanders you’ve just appointed. The medium-term implications are less reassuring.

If Xi completes the purge cycle and consolidates control over a younger, more personally loyal officer corps, he will have removed the institutional friction that might counsel caution. The generals who remember the 1979 war with Vietnam—a costly, inconclusive campaign that revealed PLA weaknesses—are gone. Their replacements have no comparable experience of military failure.

The 2027 deadline is less than two years away. The purges have consumed much of the preparation time. Either Xi accepts that the deadline was always aspirational, or he concludes that a loyal but untested force is preferable to a capable but unreliable one.

Neither conclusion is reassuring for Taipei.

The Intelligence Gap

American analysts face an epistemic problem. The purges remove the officers whose behavior patterns they have studied for years. Replacement commanders are unknown quantities—their risk tolerance, their relationship with Xi, their likely responses under pressure. The institutional knowledge that enables prediction has been systematically destroyed.

Politico reported that some Pentagon officials see opportunity in this chaos. A PLA in turmoil is a PLA less capable of coordinated action. Deterrence becomes easier when the adversary’s command structure is unreliable.

This optimism may be misplaced. Deterrence requires that the adversary believe they will lose. It also requires that the adversary’s decision-making be rational and predictable. Purges introduce noise into both calculations. A leader who has eliminated everyone willing to tell him uncomfortable truths may believe he will win when he cannot. A command structure optimized for loyalty over competence may execute orders that competent officers would refuse.

The most dangerous adversary is not the strongest. It is the one whose behavior you cannot model.

The Thermodynamic Trap

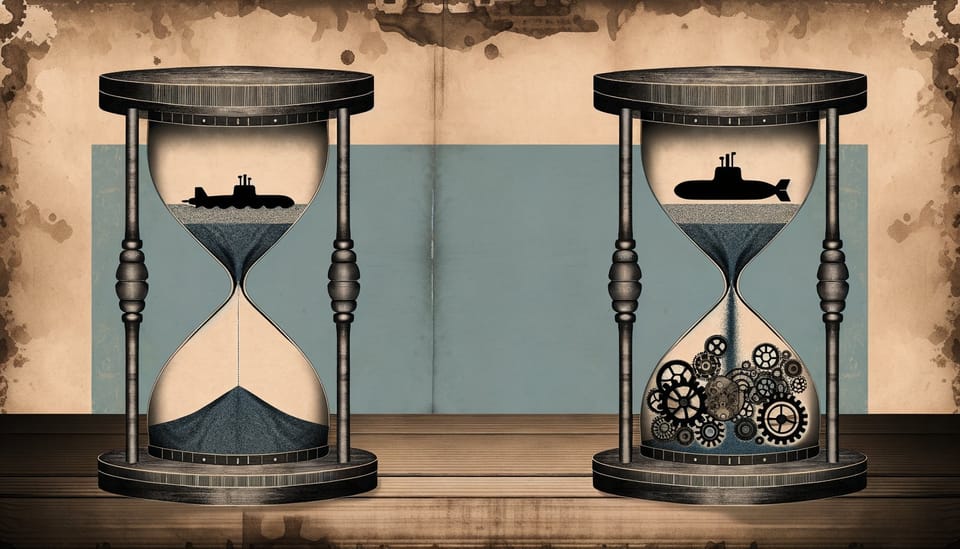

Authoritarian systems face an irreducible tension between control and capability. Tight control prevents defection but inhibits adaptation. Loose control enables innovation but invites challenge. Xi has chosen control.

The purges function as a metabolic process—clearing accumulated dysfunction, eliminating nodes of potential resistance, resetting the system to a known state. But metabolism has costs. Energy spent on internal monitoring cannot be spent on external competition. Officers focused on political survival cannot focus on operational excellence. The system becomes increasingly efficient at maintaining itself and increasingly incapable of achieving its stated purposes.

This dynamic does not resolve. It compounds. Each purge cycle removes the officers who might have balanced loyalty with competence. Their replacements understand that competence without loyalty is fatal. The selection pressure produces a force that is ideologically pure and operationally hollow.

Xi may recognize this trap. He may believe he can escape it through technology—AI-enabled command systems that reduce dependence on human judgment, autonomous weapons that don’t require trusted operators, information networks that monitor without requiring informants. The PLA’s modernization priorities suggest this bet.

Whether it will work is unknowable. No military has tested AI-enabled command in high-intensity conflict. The assumption that technology can substitute for institutional trust is untested. It may be correct. It may be the kind of assumption that looks obvious until the shooting starts.

What Breaks First

The purges will continue. Xi has demonstrated that no officer is safe, regardless of personal relationship or institutional position. The message is clear: loyalty is provisional, always subject to reassessment, never finally earned.

This produces three possible trajectories.

First, Xi achieves his goal. The officer corps internalizes total obedience. The PLA becomes an instrument of Party will, capable of executing whatever operations Xi orders. Taiwan falls. The United States is deterred. The Chinese century begins.

Second, the purges hollow out the force. Capable officers leave or are removed. Those who remain optimize for political survival. When tested—in Taiwan, in the South China Sea, in some crisis no one anticipates—the PLA fails. The failure discredits Xi and potentially the Party itself.

Third, the system reaches equilibrium. Xi purges enough to maintain control but not so many that capability collapses. The PLA becomes adequate but not excellent—capable of coercing smaller neighbors, incapable of defeating American intervention. The Taiwan question remains unresolved. The standoff continues.

The evidence supports the third trajectory. Xi is not irrational. He understands that military failure would be catastrophic. The purges target specific individuals, not entire institutions. The modernization programs continue. The exercises proceed.

But equilibrium is not stability. A system maintained through continuous purging is a system always one miscalculation from collapse. The officers who remain know they could be next. The officers who replace them know they were not first choices. The entire structure rests on a single assumption: that Xi’s judgment is correct.

History suggests caution about that assumption.

FAQ: Key Questions Answered

Q: Has Xi Jinping purged more military leaders than previous Chinese leaders? A: Yes. At least 17 PLA generals have been removed since 2012, including eight former CMC members—a rate unprecedented in post-Mao China. The 2023-2026 wave has been particularly intense, eliminating nearly the entire senior command structure formed in 2022.

Q: Does the military purge mean China won’t invade Taiwan soon? A: The purges reduce near-term invasion risk by disrupting command continuity and planning. However, they may increase medium-term risk by removing officers who might counsel caution and replacing them with untested loyalists.

Q: Why was Zhang Youxia purged despite being Xi’s close ally? A: Zhang’s willingness to resist Xi’s directives on institutional matters—combined with his independent power base from battlefield experience—made him a potential threat regardless of personal loyalty. In Xi’s system, the capacity to resist is itself disqualifying.

Q: How do the purges affect China’s military modernization goals? A: The Pentagon assesses that purges create leadership disruption but do not derail modernization toward 2027 goals. However, the loss of institutional memory and the promotion of untested officers may degrade the force’s ability to execute complex operations.

The Schrödinger’s General

The purges reveal nothing definitive about Xi’s intentions because they serve multiple purposes simultaneously. They eliminate corruption. They enforce loyalty. They buy time. They signal strength. They expose weakness. The observer cannot determine which interpretation is correct because all are correct.

Zhang Youxia is under investigation. He has not been convicted. He exists in the superposition that Xi’s system creates—guilty enough to investigate, not yet guilty enough to sentence. The uncertainty is the punishment. The uncertainty is the message. The uncertainty is the point.

Western analysts will continue debating whether the purges signal war preparation or regime fragility. They will produce classified assessments and academic papers and think-tank reports. They will be wrong, not because their analysis is flawed, but because the question assumes a distinction that Xi’s system has collapsed.

The PLA is being prepared for war. The regime is fragile. These are not alternatives. They are the same condition, viewed from different angles. A system that must purge its highest commanders to ensure obedience is a system that doubts its own foundations. A leader who eliminates everyone capable of independent judgment is a leader who believes independent judgment threatens him.

Xi Jinping has built a military that will follow orders. Whether it can win a war is a question that remains—like Zhang Youxia’s fate—in superposition.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- Pentagon China Military Power Report 2024 - Primary source for PLA modernization assessments and budget estimates

- Jamestown Foundation analysis - Expert assessment of purge patterns and promotion dynamics

- The Guardian coverage - Breaking news on Zhang Youxia investigation and PLA Daily statements

- Vox analysis - Assessment of purge implications for Taiwan scenarios

- Politico National Security Daily - Pentagon perspective on intelligence implications

- NDU Press study - Academic analysis of PLA reform trajectory

- Cambridge study on faction decline - Scholarly research on purge effects on decision-making