Why Taiwan's missile defense will fail in the first hours of a Chinese attack

Taiwan has spent billions on Patriot batteries and indigenous interceptors. But the brutal arithmetic of saturation warfare means its layered defenses will likely collapse within hours of a serious Chinese strike—not from technological failure, but from the physics of fighting an adversary with...

🎧 Listen to this article

Six Minutes to Midnight

Taiwan’s PAVE PAWS radar station on Mount Leshan provides approximately six minutes’ warning of incoming Chinese ballistic missiles. In that narrow window, operators must detect, classify, and track hundreds of inbound threats while simultaneously cueing interceptors, confirming engagement authority, and coordinating across a layered defense architecture that has never been tested against a peer adversary. The People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force knows this timeline intimately. They have built their entire Taiwan strike doctrine around compressing it to nothing.

The island’s missile defense system represents one of the most expensive military investments in Asia—billions of dollars poured into Patriot batteries, indigenous Sky Bow interceptors, and command networks designed to knit everything together. Yet the uncomfortable truth that Taipei’s defense planners privately acknowledge is that this architecture will likely fail catastrophically in the opening hours of any serious Chinese attack. Not because the technology doesn’t work. Not because Taiwan’s military lacks competence. But because the fundamental mathematics of saturation warfare render layered defense a losing proposition when the attacker possesses the world’s largest land-based missile arsenal and the willingness to use it all at once.

Understanding why requires moving beyond the comforting narratives of deterrence and examining the brutal physics of what happens when 900 short-range ballistic missiles, 1,300 medium-range missiles, and an unknown quantity of cruise missiles converge on an island roughly the size of Maryland.

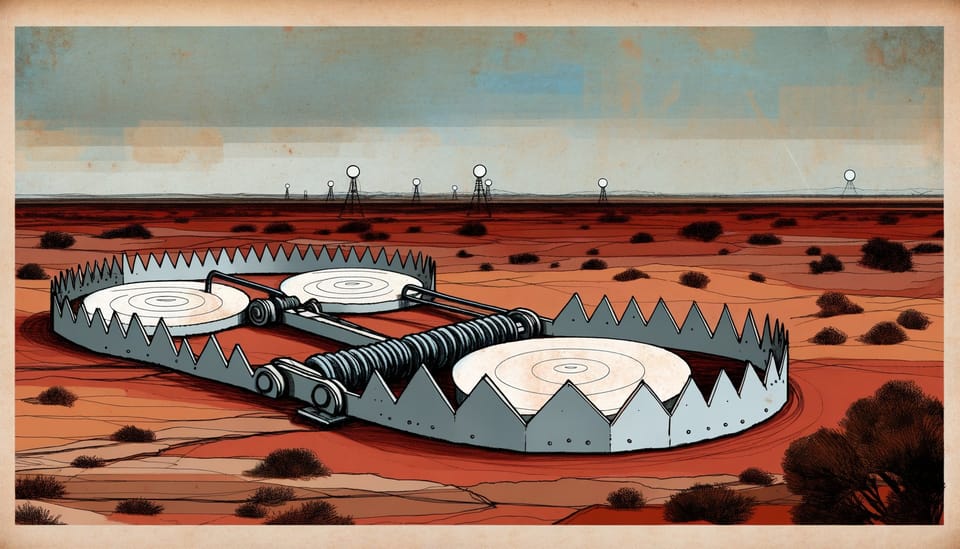

The Geometry of Exhaustion

Taiwan’s air defense architecture looks impressive on paper. Seven Patriot batteries provide point defense around critical targets. Twelve Sky Bow III batteries offer medium-range coverage. The indigenous T-Dome program promises to integrate these systems with NASAMS and an IBCS-like command network. Total investment since 2020 exceeds $16 billion, with the Sea-Air Combat Power Improvement Plan allocating another $8 billion for mass production of nine missile types through 2026.

The problem is not capability. It is capacity.

A single Patriot battery carries between 16 and 24 ready missiles depending on configuration. Assume Taiwan’s seven batteries average 20 missiles each. That yields 140 interceptors available for immediate engagement. Sky Bow III batteries carry roughly 6-8 missiles per launcher with 4-6 launchers per battery—call it 350 additional interceptors across all twelve batteries. Taiwan’s total ready magazine for ballistic missile defense sits somewhere around 500 interceptors, possibly less given maintenance rotations and training allocations.

China’s Rocket Force can launch 900 short-range ballistic missiles in a single salvo. Not over days. Not in waves. In the first hour.

Each incoming ballistic missile requires multiple interceptors to achieve acceptable kill probability. The Patriot system’s single-shot kill probability against maneuvering reentry vehicles hovers around 50-70% under optimal conditions—conditions that include clear tracking data, functioning radar, intact command links, and operators who aren’t simultaneously managing dozens of simultaneous engagements while their facilities shake from nearby impacts. Against a single missile, defenders typically fire two interceptors to push cumulative kill probability above 90%. Against hypersonic glide vehicles like the DF-17, which the Pentagon’s 2024 China Military Power Report identifies as part of China’s “world’s leading hypersonic missile arsenal,” even two-shot doctrine may prove insufficient.

Run the numbers. Five hundred interceptors. Two shots per target. Taiwan can theoretically engage 250 incoming missiles—assuming perfect coordination, zero system failures, and no degradation from electronic warfare. China can launch four times that number before breakfast.

The Reload That Never Comes

Magazine depth compounds the problem. Patriot launchers require 20-30 minutes to reload under peacetime conditions with trained crews and functioning logistics. During active combat, with airfields cratered, supply depots burning, and communications degraded, that timeline stretches toward infinity. Sky Bow systems face similar constraints. Taiwan’s entire defensive concept assumes the ability to absorb an initial attack, reload, and continue fighting.

The PLA’s doctrine assumes something different: that there won’t be a second engagement.

Chinese military planners have studied American air defense operations for decades. They understand that Western systems are designed for sustained campaigns—the assumption being that initial salvos will be absorbed, lessons learned, and subsequent attacks met with improved coordination. The Rocket Force has optimized for a different model: overwhelming concentration in the first strike, targeting not just military assets but the reload capacity itself. Ammunition depots. Launcher maintenance facilities. The roads connecting them.

Taiwan’s Central Mountain Range, which dominates the island’s geography, creates additional complications. Radar systems positioned on the western plains can see incoming threats from the mainland but struggle with low-altitude cruise missiles hugging the terrain. Systems positioned higher face line-of-sight limitations in the valleys. The mountains themselves create massive radar shadows on the eastern slopes, allowing PLA cruise missiles to approach from unexpected azimuths after circling the island’s periphery.

The defenders face a geometric puzzle with no clean solution. Cover the obvious approach corridors and leave gaps elsewhere. Spread coverage thin and accept reduced engagement capacity everywhere. Either choice creates exploitable seams.

When the Network Becomes the Target

Taiwan’s response to the saturation problem has been integration. The T-Dome program and associated command networks aim to create a unified air picture, allowing any sensor to cue any shooter and enabling dynamic reallocation of interceptors as threats develop. In theory, this transforms isolated batteries into a coherent defensive system greater than the sum of its parts.

In practice, it creates a single point of failure.

Modern integrated air defense networks depend on data links, processing nodes, and communication infrastructure that are themselves targetable. The PLA has invested heavily in electronic warfare capabilities specifically designed to degrade these connections. GPS jamming denies precision timing. Broadband noise jamming blinds radars. Targeted cyber attacks can corrupt the data flowing between sensors and shooters, creating what engineers call “false data injection”—a technique where adversaries manipulate sensor inputs to make the system see threats that don’t exist or miss threats that do.

Consider what happens when Taiwan’s integrated network receives conflicting data from multiple sensors about a single incoming missile’s trajectory. The system must reconcile these inputs in milliseconds. If one sensor has been compromised—or simply degraded by jamming—the resulting track may be subtly wrong. The interceptor launches on a false solution. The real missile continues unimpeded.

The more systems Taiwan integrates, the greater the attack surface for this kind of corruption. Research on cascading failures in complex networks suggests that highly connected systems can experience catastrophic collapse from relatively small perturbations. A successful cyber attack on a single node can propagate failures throughout the network faster than human operators can diagnose and isolate the problem.

Taiwan’s defenders face a cruel irony: the very integration that enables effective defense against conventional attacks creates vulnerabilities that a sophisticated adversary can exploit.

The Human Factor

Automated systems can process threats faster than human operators, but Taiwan’s rules of engagement require human authorization for interceptor launches. This creates a decision bottleneck precisely when speed matters most.

Six minutes of warning. Hundreds of incoming missiles. Each engagement decision requires confirmation that the target is hostile, that the proposed intercept solution is valid, that firing won’t create worse problems—like fratricide against friendly aircraft or wasted interceptors against decoys. Operators must make these calls while alarms blare, displays saturate with contacts, and the knowledge that their families live under the incoming warheads weighs on every decision.

Stress degrades cognitive performance. Cortisol floods the system, narrowing attention and impairing the kind of flexible thinking that complex tactical situations demand. Training helps, but no simulation fully replicates the psychological weight of actual combat. Taiwan’s air defense operators have never faced anything like what the PLA can deliver. Neither has anyone else.

The alternative—removing humans from the loop and allowing automated engagement—creates different problems. Automation bias leads operators to trust system recommendations even when those recommendations are wrong. Fully autonomous systems can be spoofed by sophisticated electronic warfare. And the political implications of delegating life-and-death decisions to algorithms remain unresolved in Taiwan’s defense establishment, where Confucian traditions of hierarchical authority still shape institutional culture.

Wellington Koo, Taiwan’s defense minister, has pushed for faster decision cycles and reduced ceremony in military operations. But changing institutional culture takes years. The PLA’s missiles arrive in minutes.

The Cost of Symbolism

Taiwan’s defended asset list reveals another vulnerability: the tension between what must be protected and what can be protected.

Political logic demands defense of symbolic targets—the Presidential Office, the Ministry of National Defense, the legislature. These buildings represent sovereignty. Their destruction would be a propaganda victory for Beijing regardless of military significance. Taiwan’s defense planners cannot ignore them.

Military logic demands defense of operational assets—air bases, naval facilities, command bunkers, ammunition depots. These enable continued resistance. Their loss degrades fighting capacity directly.

The problem is that Taiwan cannot defend both adequately. Every interceptor allocated to protecting a symbolic target is one less available for military assets. Every radar tracking potential threats to government buildings is one less tracking threats to operational infrastructure.

The PLA understands this dilemma. Chinese targeting doctrine explicitly accounts for the defender’s need to protect politically significant sites that may have limited military value. By threatening symbolic targets, the Rocket Force forces Taiwan to dilute its defensive coverage, creating gaps that can be exploited against military objectives.

This dynamic inverts the usual cost-exchange calculations. Taiwan spends $10 million intercepting a $1 million missile aimed at a building that has no military function—and in doing so, leaves a $500 million air base undefended. The economics favor the attacker at every level.

What Breaks First

The most likely failure sequence begins not with interceptor exhaustion but with sensor degradation. Taiwan’s early warning radars are large, stationary, and well-mapped by Chinese intelligence. They will be among the first targets of any serious attack—not necessarily destroyed, but degraded through electronic warfare and precision strikes on supporting infrastructure.

Blind radars cannot cue interceptors. Interceptors without cueing cannot engage. The layered defense architecture collapses from the top down.

What follows depends on how much of Taiwan’s command network survives the initial cyber and electronic warfare campaign. If the T-Dome integration holds, remaining batteries can still coordinate. If it fragments, each battery fights alone—effective against local threats but unable to mass fires against concentrated attacks.

The RAND Corporation’s analysis of Taiwan’s capacity to resist a major Chinese attack concluded that “even if Taiwan’s political leadership and social cohesion are strong and its military is expected to be effective against China’s military, U.S. military intervention would be required for Taiwan to withstand a major attack.” This assessment assumes Taiwan’s defenses function as designed. If they fail in the first hours, the timeline for effective resistance compresses dramatically.

What Could Change

Taiwan’s defensive problem has no clean solution, but it has mitigation strategies that Taipei has been slow to implement.

Dispersion is the most obvious. Mobile launchers are harder to target than fixed sites. Distributed sensors create redundancy that single-point failures cannot collapse. Taiwan has moved in this direction—the Sky Bow IV program emphasizes mobility—but institutional inertia and budget constraints have slowed implementation.

Hardening offers another path. Underground facilities can survive strikes that would destroy surface installations. Taiwan has extensive tunnel networks, but converting them to operational military use requires investment that competes with other priorities.

Deception complicates the attacker’s targeting problem. Decoy launchers, fake radar emissions, and deliberate ambiguity about actual capabilities force the PLA to expend ordnance against uncertain targets. Taiwan has historically been reluctant to embrace deception at scale, viewing it as inconsistent with democratic transparency. This may be a luxury it cannot afford.

The most effective mitigation, however, lies outside Taiwan’s control: American intervention. U.S. naval and air assets operating from Guam, Japan, and carrier groups could provide the defensive depth that Taiwan lacks. But American forces face their own saturation challenges from China’s anti-access/area-denial systems, and political will for intervention remains uncertain.

The Uncomfortable Truth

Taiwan has spent billions building a missile defense system that serves primarily as a political symbol rather than a military solution. This is not waste—symbols matter in deterrence, and the existence of any defense complicates Chinese planning. But it is also not the impenetrable shield that public discourse sometimes suggests.

The honest assessment is that Taiwan’s missile defenses will exact a cost from any Chinese attack while failing to prevent catastrophic damage. They will shoot down some missiles, protect some targets, and buy some time. They will not stop a determined assault by an adversary willing to accept losses and expend ordnance at scale.

This reality shapes Taiwan’s broader defense strategy, which increasingly emphasizes asymmetric capabilities—anti-ship missiles, mines, and systems designed to make invasion costly rather than impossible. The “porcupine” doctrine accepts that Taiwan cannot win a symmetric fight against the PLA. It aims instead to ensure that victory costs China more than it gains.

Missile defense fits awkwardly into this framework. It is expensive, symmetric, and ultimately inadequate against the threat it faces. But abandoning it entirely would send signals that Taipei cannot afford to send. Taiwan remains trapped between military logic and political necessity, spending billions on systems that everyone privately acknowledges will fail while publicly insisting they will succeed.

The six-minute warning from Mount Leshan will come someday. When it does, Taiwan’s defenders will do their best with what they have. It will not be enough.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: How many missiles can Taiwan’s defense system actually intercept? A: Taiwan’s combined Patriot and Sky Bow systems can engage roughly 250-300 incoming missiles before exhausting ready magazines, assuming optimal conditions and two interceptors per target. China can launch over 900 short-range ballistic missiles in a single salvo, plus cruise missiles and hypersonic weapons.

Q: Why doesn’t Taiwan just buy more interceptors? A: Interceptor costs create an unfavorable exchange ratio—Taiwan spends approximately $3-10 million per interceptor to defeat missiles costing China $500,000-2 million each. More fundamentally, launcher capacity and reload times limit how many interceptors can be employed regardless of stockpile size.

Q: Could U.S. intervention solve Taiwan’s missile defense problem? A: American forces could provide significant additional defensive capacity, but they face their own challenges from China’s anti-access systems. The RAND Corporation assesses that U.S. military intervention would be required for Taiwan to withstand a major attack, but American forces would need days to weeks to fully deploy—time Taiwan’s defenses must buy.

Q: What is Taiwan doing to address these vulnerabilities? A: Taiwan is pursuing mobile launchers (Sky Bow IV), distributed sensors, underground hardening, and integration with U.S. systems. However, institutional constraints and budget competition have slowed implementation. The “porcupine” strategy increasingly emphasizes asymmetric capabilities over traditional air defense.

The Waiting Game

Taiwan’s missile defense architecture embodies a contradiction that its planners understand but cannot publicly acknowledge. The billions spent on Patriots and Sky Bows purchase not invulnerability but time—hours, perhaps days, during which the international community must decide whether to intervene. The systems exist less to defeat Chinese missiles than to demonstrate that Taiwan has done everything possible to defend itself, establishing the moral and political foundation for allied support.

This is not a criticism. In the brutal calculus of deterrence, perception matters as much as capability. A Taiwan that invested nothing in missile defense would invite aggression by signaling resignation. A Taiwan that claims its defenses are impenetrable invites disaster by encouraging complacency.

The honest position lies between: Taiwan’s defenses will impose costs, buy time, and fail. What happens after that failure depends on decisions made in Washington, Tokyo, and Beijing—decisions that Taiwan’s billions in spending can influence but not determine.

Mount Leshan’s radars continue their patient scan of the Taiwan Strait. Somewhere across the water, the Rocket Force waits. The six-minute clock has not yet started. But everyone knows it will.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- RAND Corporation: Can Taiwan Resist a Large-Scale Military Attack by China? - Framework for assessing Taiwan’s 90-day resistance capacity

- U.S. Department of Defense China Military Power Report 2024 - Assessment of PLA Rocket Force capabilities and hypersonic arsenal

- Taiwan Defense Report 2025: Area Denial Progress - Details on Sea-Air Combat Power Improvement Plan

- Army University Press: PLA Rocket Force Analysis - Comprehensive assessment of Chinese missile inventory

- False Data Injection Attacks in Control Systems - Technical analysis of cyber vulnerabilities in integrated systems

- Barr Group: Patriot Missile Failure Case Study - Historical analysis of software-induced defense failures

- AAAS: Ground-Based Missile Defense System Flaws - Expert assessment of missile defense limitations