Why NATO cannot stop Russian attacks on undersea cables it sees coming

The alliance's surveillance network tracks every suspicious vessel in the Baltic. Its legal framework, ownership structures, and decision-making architecture ensure that watching is all it can do. Russia has learned to exploit the gap.

🎧 Listen to this article

The Seabed’s Quiet War

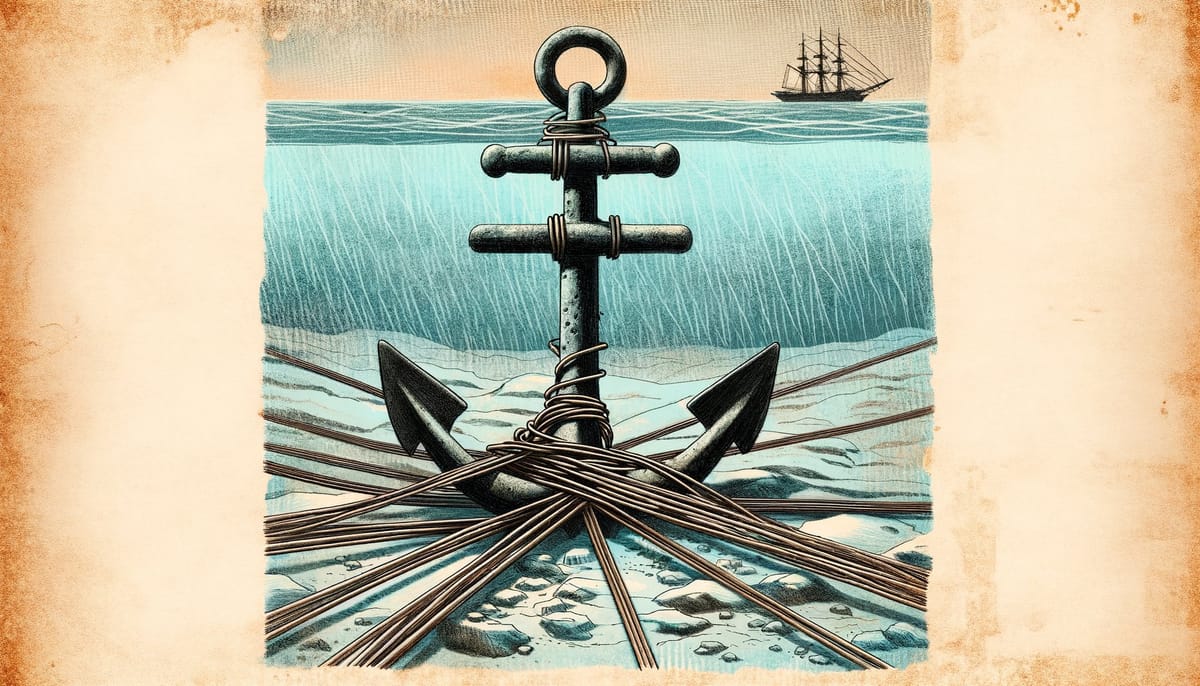

In November 2024, a Chinese-flagged bulk carrier named Yi Peng 3 dragged its anchor across the Baltic seabed for more than a hundred miles, severing two undersea cables connecting Sweden, Lithuania, Finland, and Germany. Danish and Swedish naval vessels shadowed the ship for weeks. NATO knew what had happened. Everyone knew. The cables stayed cut.

This was not an intelligence failure. NATO’s surveillance architecture had tracked the vessel throughout its destructive transit. The alliance’s problem was not detection but response—a paralysis rooted not in capability but in the architecture of international law, the economics of private infrastructure, and the structural mismatch between how democracies make decisions and how authoritarian states exploit that process.

The question is not why NATO cannot see these attacks coming. The question is why seeing them changes nothing.

The Surveillance That Cannot Act

NATO maintains one of the most sophisticated maritime surveillance networks on Earth. The alliance’s Maritime Domain Awareness infrastructure aggregates Automatic Identification System data, satellite imagery, acoustic sensors, and intelligence from thirty member states into a unified operational picture. When suspicious vessels approach critical infrastructure, NATO knows.

The Yi Peng 3 incident demonstrated this capability with uncomfortable clarity. European navies tracked the vessel as it transited the Baltic, observed it lower its anchor in waters far too deep for legitimate anchoring, and monitored its path as it systematically crossed cable routes. The Danish and Swedish navies maintained visual contact for weeks after the incident. Attribution was never in doubt.

Yet the ship eventually sailed away. No boarding occurred. No arrests were made. The cables were repaired at commercial expense. Russia’s shadow fleet learned that surveillance without consequence is merely expensive observation.

This gap between detection and response reflects a structural problem that technology cannot solve. The legal framework governing undersea infrastructure dates to 1884, when the Convention for the Protection of Submarine Telegraph Cables established flag-state jurisdiction over vessels damaging cables. UNCLOS Article 113 preserved this framework: only the state whose flag a vessel flies can prosecute cable damage in international waters. When that flag belongs to a state with no interest in prosecution, the legal mechanism fails by design.

The forensic burden compounds this structural weakness. Approximately 150 cable faults occur annually from anchors and fishing gear—a statistical baseline that transforms deliberate sabotage into plausible accident. When a vessel drags an anchor across a cable, the physical damage is indistinguishable from negligent seamanship. The Atlantic Council has noted that international law provides no mechanism for coastal states to enforce cable protection beyond territorial waters, creating what analysts call a “permission zone” for infrastructure attacks.

The Consensus Trap

NATO’s decision-making architecture was designed to prevent any single member from dragging the alliance into unwanted conflict. This feature has become a vulnerability.

Article 5’s collective defense guarantee requires unanimous agreement that an “armed attack” has occurred. The drafters deliberately set this threshold high—they wanted to ensure that treaty obligations would not automatically trigger war. As defense analysts have observed, the framework was “deliberately structured to avoid forcing allies into war.”

Russia exploits this structure with surgical precision. Cable cuts, pipeline damage, and infrastructure harassment are calibrated to inflict economic harm while remaining below the threshold that would compel collective response. Each incident individually fails to meet the “armed attack” standard. The cumulative effect—degraded connectivity, increased insurance costs, diverted naval resources—accrues without triggering the defensive mechanisms designed to prevent exactly this outcome.

The alliance’s thirty-member structure creates additional friction. Each member brings different threat perceptions, risk tolerances, and domestic political constraints. Southern European members prioritize Mediterranean migration; Baltic states see Russian infrastructure attacks as existential; Western European economies weigh the costs of escalation against the benefits of stable energy prices. Achieving consensus on graduated responses requires months of negotiation. Russia operates on different timescales.

This temporal mismatch runs deeper than bureaucratic inefficiency. Democratic governments reset strategy every four years when elections change leadership. Budget cycles constrain investment horizons. Parliamentary oversight requires transparency that reveals defensive postures. Russia’s strategic culture, by contrast, operates on generational timescales. The Main Directorate of Deep-Sea Research (GUGI)—Russia’s specialized undersea warfare unit—maintains institutional continuity across decades. Its operational planning assumes patience that democratic systems cannot match.

The Ownership Void

Undersea cables are critical national infrastructure owned by private corporations. This contradiction shapes everything.

Fifty-nine percent of the world’s submarine cables are privately owned, primarily by telecommunications consortia and technology giants. These companies optimize for commercial returns, not national security. Their redundancy calculations use N+1 models—adequate for routine failures but insufficient for coordinated attacks. NATO’s security requirements would demand 2N redundancy, doubling capital expenditure for protection against threats that may never materialize.

The economic incentives actively discourage protection. Cable operators compete on cost. Investment in hardened routes, deeper burial, or redundant paths reduces margins without generating revenue. Security improvements benefit all users but cost individual operators—a classic free-rider problem that market mechanisms cannot solve.

Insurance markets compound this dysfunction. Lloyd’s mandatory exclusions for state-backed cyber attacks, implemented in 2025, created coverage voids precisely as Baltic sabotage accelerated. War risk exclusions incentivize asset owners to resist governmental attribution of incidents as hostile acts. If damage remains classified as “mysterious” or “accidental,” standard policies apply. If governments declare sabotage, coverage evaporates. Private operators have financial reasons to prefer ambiguity.

The repair fleet illustrates the structural mismatch between commercial and security imperatives. Approximately sixty specialized cable repair ships exist worldwide—vessels costing hundreds of millions of dollars, maintained on standby for emergencies that may never occur. Commercial operators bear these costs because contracts require 24-hour dispatch capability. But the fleet is aging, and shipbuilding investment has pivoted toward environmentally compliant vessels. The infrastructure that enables repair is itself becoming obsolete.

The Attribution Paradox

International law requires proof that NATO cannot obtain without violating international law.

The International Court of Justice’s “effective control” standard—established in the Nicaragua case—requires demonstrating that a state directed or controlled the specific conduct in question. Intelligence agencies can achieve high confidence through signals and human intelligence that Russian vessels conducted sabotage. Converting that confidence into legally admissible evidence requires physical access to vessels, crews, and communications that flag-state jurisdiction protects.

UNCLOS Article 92 grants exclusive jurisdiction to flag states over vessels in international waters. NATO forces cannot board a Russian-flagged vessel without Russian consent. They cannot board a Chinese-flagged vessel without Chinese consent. Shadow fleet operators register vessels under flags of convenience—Cameroon, Gabon, Palau—states with neither capacity nor interest in enforcement. The legal framework assumes good-faith cooperation that adversarial operations are designed to deny.

This creates an evidentiary loop that cannot close. NATO needs physical evidence to justify boarding. It can only obtain physical evidence through boarding. The infrastructure saboteur operates in a legal void where the act of investigation would itself violate the law being enforced.

The CSIS has documented how this attribution gap enables “implausible deniability”—a strategy where Russia’s involvement is obvious to all observers but legally unprovable. The transparency of the lie prevents definitive response while forcing NATO to expend resources evaluating claims everyone knows are false. Ambiguity is not the goal. Paralysis is.

The Deterrence Deficit

Military forces optimized for high-intensity conflict cannot deter low-intensity harassment.

NATO’s deterrence architecture assumes identifiable adversaries, clear thresholds, and proportional response options. Nuclear weapons deter nuclear attack. Conventional forces deter conventional invasion. The alliance’s strength lies in escalation dominance—the credible threat that aggression will be met with overwhelming force.

Infrastructure sabotage exploits the gap between these capabilities and the actual threat. The measures that would prevent gray-zone attacks—boarding vessels in international waters, mining infrastructure approaches, deploying autonomous defensive systems—are structurally identical to acts of war. Analysts note that democratic states face legal and ethical constraints on developing offensive capabilities that authoritarian adversaries do not share. The asymmetry is not temporary. It is architectural.

Russia has discovered that nuclear-era restraint norms create a price ceiling on infrastructure attacks. Sabotage can be calibrated to stay below thresholds that would trigger Article 5 or escalation, effectively weaponizing NATO’s own prudence. The alliance’s strength in preventing catastrophic conflict becomes weakness in preventing chronic degradation.

The Baltic Sentry patrols—NATO’s visible response to cable incidents—illustrate this dynamic. Naval vessels patrol cable routes, demonstrating presence and solidarity. The patrols are necessary for alliance cohesion. They are insufficient for deterrence. A frigate cannot prevent an anchor drop. Surveillance confirms what happened; it does not prevent what happens next.

The Resilience Question

How vulnerable is NATO actually? The answer is less alarming than headlines suggest—and more concerning than resilience metrics imply.

Submarine cables carry 99% of intercontinental internet traffic. This statistic, frequently cited, obscures significant redundancy. When Baltic cables were severed in 2024, traffic rerouted within hours. Financial systems continued operating. Military communications shifted to satellite backup. The immediate disruption was manageable.

But resilience under peacetime conditions differs from resilience under coordinated attack. Current redundancy assumes sequential failures—one cable breaks, traffic shifts to another. Hybrid warfare targets the coordination layer between redundant elements. Simultaneous cuts across multiple routes would overwhelm rerouting capacity. The EU’s recent action plan acknowledges that “the pattern observed in recent months particularly in the Baltic Sea suggests that this critical infrastructure is increasingly the target of deliberate hostile acts.”

The economic costs compound over time. Each incident increases insurance premiums. Each repair diverts specialized vessels from other routes. Each investigation consumes intelligence resources. The strategy is not catastrophic disruption but chronic degradation—a tax on Western connectivity that accumulates without triggering defensive mechanisms.

Energy infrastructure presents different vulnerabilities. The Nord Stream explosions in 2022 demonstrated that pipelines cannot be rerouted. Unlike data, gas requires physical delivery. The Balticconnector pipeline damage in 2023 affected Finnish energy security for months. Redundancy in energy infrastructure requires years of construction, not software updates.

What Would Actually Work

Effective protection requires changes that NATO members have not demonstrated willingness to make.

First, legal frameworks must shift from flag-state to coastal-state jurisdiction for infrastructure protection zones. This would require amending UNCLOS or establishing regional agreements that override its provisions. Neither is impossible—the EU’s cable security action plan moves in this direction—but both require sustained diplomatic effort against states benefiting from current ambiguity.

Second, ownership structures must align commercial incentives with security requirements. Options include direct government ownership of critical routes, mandatory security standards for private operators, or public-private partnerships that socialize protection costs. Each approach faces political resistance. Nationalization contradicts market principles. Regulation increases costs. Partnerships require budget allocations that compete with other priorities.

Third, response options must expand beyond surveillance and symbolic patrols. This means accepting legal and diplomatic friction from more assertive maritime postures—inspecting suspicious vessels, establishing exclusion zones around critical infrastructure, developing capabilities for seabed defense that currently do not exist. The trade-off is explicit: effective protection requires actions that risk escalation.

The most likely trajectory is none of these. NATO will continue improving surveillance, coordinating responses, and issuing statements. Cables will continue being cut. The alliance will absorb the costs because the costs, while significant, remain below the threshold that would compel structural change. Russia will continue exploiting the gap between what NATO can see and what NATO can do.

This is not failure in the conventional sense. It is equilibrium—an outcome where all parties act rationally within their constraints and the result satisfies no one. NATO cannot stop attacks it can see coming because stopping them would require becoming something other than what it is: a defensive alliance of democracies operating under legal constraints that its adversaries do not share.

The seabed war will continue. The question is whether cumulative damage eventually shifts the calculus—or whether the alliance discovers that chronic degradation, like chronic illness, becomes something you learn to live with rather than cure.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Why doesn’t NATO just board suspicious vessels near undersea cables? A: International law grants exclusive jurisdiction to flag states over vessels in international waters. NATO forces cannot legally board a foreign-flagged vessel without that state’s consent, and shadow fleet operators deliberately register under flags of states that will not cooperate with Western enforcement.

Q: How much damage have Russian attacks actually caused to undersea infrastructure? A: Since 2022, at least eleven confirmed or suspected incidents have affected Baltic Sea cables and pipelines, including the Nord Stream explosions and multiple cable cuts affecting Nordic and Baltic states. While individual incidents caused temporary disruption, traffic rerouting limited immediate impact. The cumulative economic cost—including repairs, increased insurance, and diverted military resources—runs into hundreds of millions of euros.

Q: Could NATO declare cable attacks an “armed attack” under Article 5? A: Theoretically yes, but practically unlikely. Article 5 requires unanimous agreement among thirty members that an armed attack has occurred. Individual cable cuts, even when clearly deliberate, fall below the threshold that would compel such consensus. Russia calibrates its operations precisely to avoid triggering collective defense mechanisms.

Q: What would effective undersea infrastructure protection actually require? A: Three structural changes: shifting legal jurisdiction from flag states to coastal states for infrastructure protection zones; aligning private ownership incentives with public security requirements through regulation or nationalization; and developing response capabilities beyond surveillance, including exclusion zones and seabed defense systems. Each requires political will that NATO members have not yet demonstrated.

The Equilibrium Below

The Baltic Sea’s cables will be repaired. They will be cut again. NATO will watch, document, and condemn. Russia will deny, delay, and continue. The pattern has become predictable because it reflects structural forces that neither side can easily change.

For NATO, the constraint is constitutional. Democracies cannot wage persistent low-intensity conflict without legal authorization, public support, and alliance consensus. These requirements take time that adversaries exploit. The alliance’s legitimacy depends on constraints that limit its effectiveness.

For Russia, the constraint is capability. Shadow fleet operations impose costs but cannot achieve strategic objectives beyond harassment. Cutting cables does not win wars. It merely demonstrates that winning peace is harder than it looks.

The seabed has become a laboratory for a new kind of conflict—one where the strongest alliance in history discovers that strength is contextual, and the rules it built to prevent catastrophe also prevent response to something less than catastrophe but more than peace.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- NATO Official Texts on Hybrid Threats - NATO’s formal definition and strategic framework for hybrid warfare

- NOAA International Framework on Submarine Cables - Legal foundations of undersea infrastructure protection under UNCLOS

- Atlantic Council Analysis on Cable Protection Gaps - Assessment of international law inadequacies

- CSIS Strategic Technologies Blog on Subsea Threats - Analysis of NATO’s surveillance-response gap

- EU Action Plan on Cable Security - European Union’s 2025 policy response to Baltic incidents

- Defense News on Legal Challenges - Reporting on NATO’s legal constraints

- DWF Group on Global Cable Risks - Insurance and liability analysis

- Forbes on Law and Undersea Cables - Assessment of legal protection failures