Why Gulf allies would abandon the US before American strike capability fails

If Washington loses access to Gulf bases for Iran operations, the question is not whether military capability or regional alliances break first—it is why the alliances are already fracturing while the Pentagon adapts.

🎧 Listen to this article

The Geometry of Abandonment

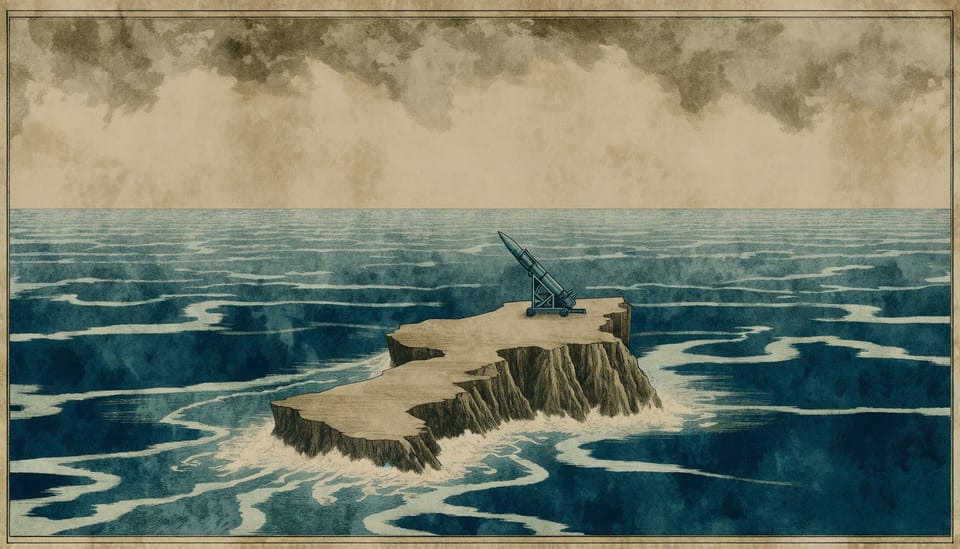

In the summer of 2025, American war planners confronted a scenario they had long dismissed as theoretical: every Gulf state declining to host or support strikes against Iran. The question was not whether Washington could still hit Iranian targets—it could, from submarines and distant bomber bases—but whether the architecture of American influence in the Middle East would survive the attempt.

The conventional framing presents this as a choice between two failure modes: military capability degrading first, or regional alliances fracturing. This framing is wrong. The two are not sequential options but coupled systems. Stress one and you stress the other. The real question is which coupling proves tighter—and what that reveals about the nature of American power in the Gulf.

The answer, uncomfortable as it may be for Pentagon planners and State Department diplomats alike, is that alliances break first. Not because Gulf rulers are disloyal or American military technology inadequate, but because the fundamental bargain underlying the relationship has shifted. Gulf states no longer need American protection the way they once did. And they increasingly fear that American protection comes bundled with American wars.

The Bargain Erodes

For three decades, the Gulf security architecture rested on a simple exchange: American military presence deterred Iranian aggression, and Gulf states provided basing, overflight, and political cover. The arrangement worked because both sides needed it. Gulf monarchies lacked the military capacity to defend themselves. Washington needed forward positions to project power.

That calculus has changed. Not completely—but enough to matter.

Consider the numbers. The UAE now fields an air force with over 130 combat aircraft, including F-16E/F Block 60 variants more advanced than many in American allied inventories. Saudi Arabia has spent $100 billion on defense since 2015, building indigenous capabilities while purchasing everything from THAAD batteries to advanced surveillance systems. Qatar hosts Al Udeid Air Base—the largest American installation in the Middle East, with approximately 10,000 troops—but has simultaneously invested billions in air defense systems that would function without American operators.

These investments reflect a strategic hedge. Gulf rulers want American protection but fear American entanglement. The distinction matters enormously.

When the US and Saudi Arabia signed the Strategic Defense Agreement in November 2025, the $142 billion package was celebrated as the largest defense deal in American history. Look closer and the structure reveals anxiety as much as alliance. The agreement emphasizes Saudi defense-industry localization—a 50% domestic production target by 2030—and burden-sharing arrangements that shift costs to Riyadh. This is not the language of dependence. It is the language of a relationship being renegotiated.

The Abraham Accords accelerated this dynamic. Israel, the UAE, and Bahrain now share intelligence, conduct joint training, and coordinate on maritime defense. The architecture functions—deliberately—without requiring American mediation for every interaction. Gulf states have options they lacked a decade ago.

The Iranian Calculus

Iran’s missile arsenal transforms the political economy of Gulf basing in ways American planners have been slow to internalize.

The Fattah-2 hypersonic missile, unveiled with characteristic theatrical flourish, represents not just a technical capability but a political signal. Iranian missiles can reach any American base in the Gulf within minutes. Al Udeid, Al Dhafra, Naval Support Activity Bahrain—all sit within range. The USS Abraham Lincoln, positioned in the Arabian Sea, operates under constant surveillance by Iranian drones and faces a threat envelope that includes anti-ship ballistic missiles.

This changes the calculation for Gulf rulers. Hosting American strikes against Iran no longer means accepting some abstract risk of retaliation. It means accepting near-certain missile attacks on one’s own territory. For monarchies whose legitimacy rests partly on protecting their populations from external threats, this is an intolerable proposition.

The insurance markets have priced this reality. War risk premiums for Gulf shipping have doubled since tensions escalated, with the Joint War Committee designating expanded exclusion zones around the Strait of Hormuz. Commercial insurers now treat the entire Persian Gulf as elevated risk. When Lloyd’s of London prices your territory as a war zone, political leaders notice.

Iranian strategists understand the coercive potential of this dynamic. Tehran’s retaliatory doctrine explicitly targets Gulf infrastructure—desalination plants, power stations, oil facilities—that sustains civilian life. A single successful strike on a major desalination facility could create humanitarian catastrophe in states where 90% of freshwater comes from the sea. Gulf rulers face not just military risk but existential vulnerability.

What “Breaking” Actually Means

Military capability does not break the way alliances do. It degrades, adapts, and finds workarounds.

Without Gulf basing, American strike options against Iran narrow but do not vanish. B-2 Spirit bombers can fly from Whiteman Air Force Base in Missouri, refueling over the Atlantic and Indian Ocean, to deliver precision munitions on Iranian nuclear facilities. B-52 Stratofortress aircraft can launch cruise missiles from standoff distances, operating from Diego Garcia in the British Indian Ocean Territory. Ohio-class submarines carry Tomahawk missiles capable of striking any target in Iran from international waters.

The operational constraints are significant but not insurmountable. Diego Garcia sits over 3,000 miles from Iran—a distance that imposes fuel costs, limits sortie rates, and extends mission timelines. A strike package that might generate 200 sorties daily from Al Udeid might manage 40 from Diego Garcia. The thermodynamics of power projection favor proximity.

But here is what matters: these limitations are known quantities. American planners have war-gamed Gulf-denied scenarios for years. The military can execute strikes without regional basing. It will be slower, more expensive, less flexible—but possible.

Alliances, by contrast, break in ways that cannot be easily repaired.

When Qatar or the UAE declines to host American strike operations, they are not simply imposing temporary operational constraints. They are making a political statement about the nature of the relationship. They are signaling to Iran, to China, to their own populations that American interests and Gulf interests have diverged. Once made, such signals cannot be easily retracted.

The structural dynamics here deserve attention. Gulf monarchies operate on dynastic timescales—decades, generations. American administrations operate on four-year cycles. Iranian strategic culture, shaped by millennia of Persian imperial memory and Twelver Shi’a eschatology, operates on horizons that make both look short-term. These temporal misalignments create systematic friction.

A Gulf ruler who permits American strikes against Iran today must live with Iranian hostility for the rest of his reign—and potentially his successor’s. An American president who orders those strikes may be out of office before the consequences fully materialize. The asymmetry of exposure makes Gulf cooperation increasingly costly.

The Quiet Defection

The most likely scenario is not dramatic rupture but quiet defection.

Gulf states will not formally abrogate defense agreements or expel American forces. They will impose conditions. Require advance notice. Demand veto rights over specific operations. Insist on plausible deniability. The infrastructure will remain; the permission will narrow.

This pattern has precedent. During the 2003 Iraq invasion, Saudi Arabia officially prohibited American combat aircraft from launching strikes from its territory—while quietly permitting support operations and overflight. Turkey denied transit rights for the 4th Infantry Division while allowing other forms of cooperation. The gap between formal alliance and operational access can be enormous.

For Iran strikes specifically, Gulf states face a brutal calculation. Permit American operations and accept certain retaliation. Refuse and preserve the relationship with Tehran while straining ties with Washington. The middle path—nominal cooperation with maximum restrictions—offers the least bad option.

American planners will adapt. They always do. But adaptation carries costs.

The shift to long-range standoff weapons, while operationally necessary, reads differently in regional honor-shame frameworks. Striking from submarines and distant bombers signals not strength but distance—an unwillingness to accept risk that Gulf partners interpret as unreliability. The very capabilities that preserve American strike options undermine American credibility.

The Economic Undertow

Beneath the military geometry lies an economic reality that shapes everything.

Gulf states trade extensively with Iran despite American sanctions. UAE-Iran commerce flows through Dubai’s ports and free trade zones, much of it technically legal, some of it operating in gray areas that American regulators prefer not to examine too closely. Qatari natural gas competes with Iranian exports in Asian markets. Saudi Arabia and Iran share the world’s largest conventional oil field, divided by their maritime boundary.

These economic ties create constituencies for restraint. Gulf merchant families—the trading dynasties whose wealth predates oil—maintain relationships with Iranian counterparts stretching back generations. American sanctions have strained these connections but not severed them. A war would.

The sovereign wealth funds that define Gulf economic strategy also counsel caution. Abu Dhabi’s ADIA, Saudi Arabia’s PIF, Qatar’s QIA—these institutions manage trillions of dollars in global assets. Their returns depend on stable markets and predictable rules. Regional war introduces volatility that damages portfolio performance regardless of who wins.

Chinese economic diplomacy amplifies these pressures. Beijing has positioned itself as an alternative partner—one that purchases Gulf oil without demanding political alignment, invests in infrastructure without imposing conditions, and maintains ties with Iran while cultivating Gulf relationships. The World Bank’s regional chief has warned that escalating Israel-Iran conflict could slow Gulf investment inflows significantly. Capital has options. It will exercise them.

What Washington Misunderstands

American strategic culture tends to view alliances as binary—you are with us or against us. Gulf political culture operates differently. Relationships are layered, contextual, and perpetually renegotiated. A partner who refuses one request may enthusiastically support another. Cooperation on counterterrorism does not imply cooperation on Iran. Shared interests in one domain create no obligations in others.

This flexibility frustrates American planners accustomed to alliance structures like NATO, where collective defense commitments are legally binding and politically sacred. Gulf arrangements rest on different foundations. The bilateral defense cooperation agreements that govern American basing are not treaties ratified by legislatures. They are executive arrangements that can be modified, reinterpreted, or quietly ignored.

The US-UAE Major Defense Partnership signed in May 2025 illustrates the ambiguity. The agreement promises “enhanced military-to-military cooperation, joint capability development, and long-term defense alignment.” It does not promise that UAE facilities will be available for any operation Washington chooses to conduct. The gap between framework and permission remains deliberately undefined.

Mohammed bin Zayed, the UAE’s president, embodies this strategic hedging. His Sandhurst training instilled British values of loyalty and discipline. His experience watching Qatar support Arab Spring protesters taught him that ideological movements threaten secular governance. His 1991 weapons-shopping trip to Washington as a young air force commander showed him how military power could be purchased. He wants American weapons. He does not want American wars.

Mohammed bin Salman operates from different premises but reaches similar conclusions. Saudi Arabia must transform or face irrelevance—Vision 2030 is not optional but existential. That transformation requires stability, investment, and time. A regional war would derail everything. The crown prince takes enormous risks in domestic policy precisely because he seeks to avoid risks in foreign policy that might threaten the modernization project.

The Cascade Nobody Wants

If alliances fracture before capability degrades, the cascade effects extend far beyond Iran policy.

American credibility in the Indo-Pacific depends partly on perceived reliability in the Middle East. If Gulf partners conclude that American protection comes with unacceptable strings, Asian allies will draw conclusions. Taiwan, Japan, South Korea—all watch how Washington manages its Gulf relationships. Abandonment in one theater signals potential abandonment in others.

The defense industrial base faces different pressures. Gulf states are among the largest purchasers of American weapons systems. Saudi Arabia’s $142 billion agreement, the UAE’s F-35 aspirations, Qatar’s ongoing acquisitions—these contracts sustain production lines and preserve manufacturing capabilities. A rupture in political relationships would eventually affect commercial relationships. Defense contractors lobby accordingly.

Israel’s position becomes more complicated, not less. The Abraham Accords created a framework for security cooperation that partially substitutes for American mediation. But that framework assumed continued American engagement in the region. If Washington’s Gulf relationships deteriorate, Israel loses both direct American support and indirect Arab cooperation. The normalization that seemed so promising becomes another casualty.

What Comes Next

The most probable trajectory is managed decline rather than dramatic collapse.

American forces will remain in the Gulf. The bases will stay open. The agreements will remain in force. But the scope of operations those bases can support will narrow. The political capital required to secure cooperation will increase. The reliability of access in crisis will decrease.

This is not the catastrophic failure that war planners fear. It is something more insidious: the gradual erosion of capability that occurs when allies stop trusting that American interests and their interests align.

The military can adapt. It will shift to standoff weapons, submarine-launched missiles, and long-range bombers. It will accept slower timelines and reduced sortie rates. It will find workarounds.

The alliances cannot adapt the same way. Once Gulf rulers conclude that American partnership brings more risk than protection, no amount of military capability can restore the relationship. Trust, once lost, does not regenerate on demand.

The answer to what breaks first, then, is clear: alliances. Not because Gulf states are hostile to American interests, but because they have learned to calculate those interests against their own. The era when American protection came without American wars is ending. Gulf rulers are adjusting accordingly.

Washington can accept this reality and work within its constraints, or it can insist on alliance terms that no longer reflect the underlying bargain. The first path preserves influence at reduced scope. The second path accelerates the very fracture it seeks to prevent.

The geometry of the Gulf has changed. American strategy has not yet caught up.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Could the US conduct strikes on Iran without any Gulf basing? A: Yes, but with significant constraints. B-2 bombers from Missouri, B-52s from Diego Garcia, and submarine-launched cruise missiles provide strike options. However, sortie rates would drop dramatically—perhaps 80% lower than with Gulf access—and mission flexibility would suffer. The capability exists; the efficiency does not.

Q: Why would Gulf states refuse to support US operations against Iran? A: Gulf rulers fear Iranian retaliation more than they value American approval. Iranian missiles can strike any Gulf capital within minutes. Desalination plants, power stations, and oil facilities present vulnerable targets. The calculation has shifted: cooperation with American strikes means accepting certain damage to one’s own territory.

Q: What role does China play in Gulf security calculations? A: China offers Gulf states an alternative partnership model—one that purchases oil without demanding political alignment and maintains ties with both Iran and the GCC. This gives Gulf rulers leverage in negotiations with Washington and reduces their dependence on American security guarantees.

Q: How would alliance fracture affect US credibility elsewhere? A: Indo-Pacific allies watch Gulf relationships closely. If Gulf partners conclude that American protection comes with unacceptable risks, Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea may draw similar conclusions about their own security arrangements. Credibility is not region-specific; it travels.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- CENTCOM Posture Statement 2025 – Official assessment of US military positioning and challenges in the Middle East

- US-Saudi Strategic Defense Agreement Fact Sheet – White House documentation of the November 2025 defense deal

- US-UAE Major Defense Partnership Joint Statement – Embassy statement on the May 2025 defense framework

- IISS Analysis on CENTCOM Force Posture – International Institute for Strategic Studies assessment

- World Bank Regional Chief on Gulf Investment Risks – Economic impact analysis of regional tensions

- Oxford Academic on GCC Security Alliances – Scholarly analysis of Gulf alliance structures

- Washington Institute on Abraham Accords Defense Cooperation – Assessment of Israel-UAE security ties