Why China Keeps Pouring Concrete into the South China Sea

Beijing's artificial islands violate international law, alienate neighbors, and invite American warships into contested waters. China builds them anyway. The reason reveals uncomfortable truths about its Taiwan planning horizon and the method behind apparent recklessness.

The Logic of Concrete

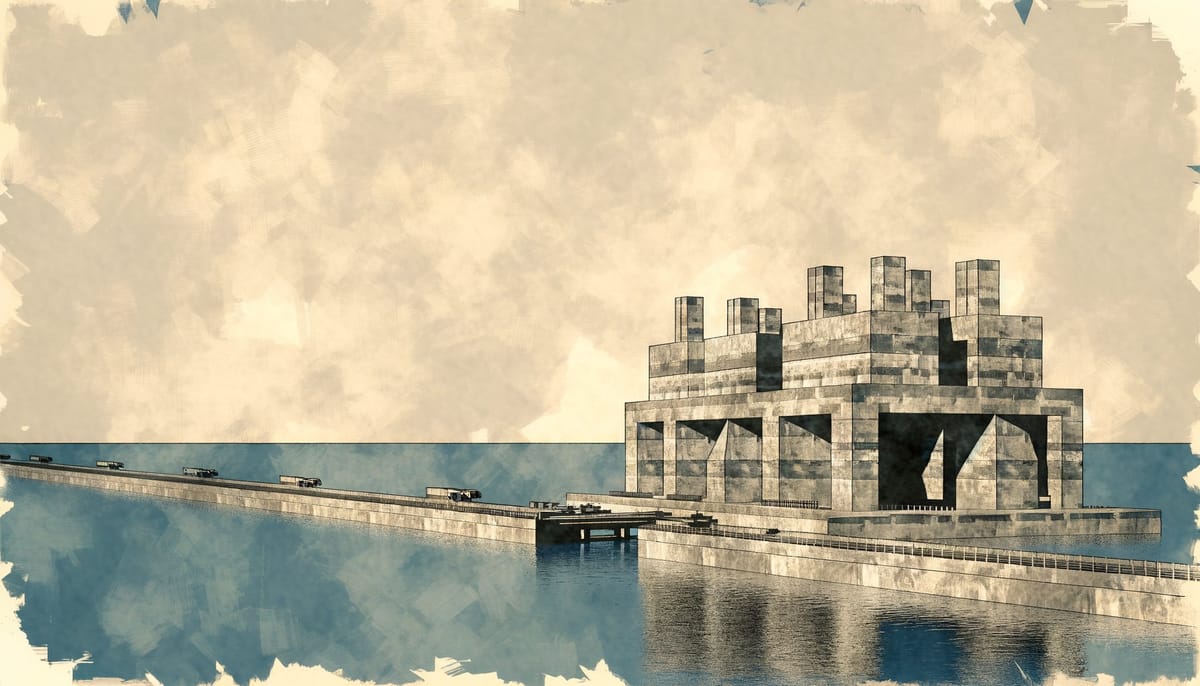

China has poured more cement into the South China Sea than any nation has ever deposited in disputed waters. The result—seven artificial islands bristling with runways, radar domes, and missile batteries—violates international law, alienates neighbors, and invites American warships to conduct provocative patrols within nautical miles of Chinese installations. Beijing does it anyway. Understanding why reveals something uncomfortable about its plans for Taiwan.

The conventional explanation frames this as nationalist overreach: Xi Jinping, captive to domestic propaganda, cannot back down without losing face. This gets the causation backwards. The South China Sea militarization is not a trap Beijing stumbled into. It is infrastructure for a war it may choose to fight.

What the Reefs Actually Do

Begin with geography. The South China Sea stretches 1.4 million square miles between Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, and Taiwan. Through it passes roughly one-third of global maritime trade—$3.4 trillion annually—including 80% of China’s oil imports. The sea’s strategic value is not theoretical. It is the jugular of East Asian commerce.

China’s artificial islands sit athwart this traffic like toll booths on a highway. Fiery Cross Reef, Subi Reef, and Mischief Reef—all now host 3,000-meter runways capable of handling any aircraft in the Chinese inventory. The Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative documented the transformation: since 2013, China has created 3,200 acres of new land where only coral and sand existed before. The U.S. Department of Defense assesses that Beijing has “fully militarized at least three large artificial island outposts” with “ports, long runways, hardened shelters, radar, and other military infrastructure.”

These are not defensive positions. Reefs cannot be defended—they can only be used, then lost. What they provide is reach.

The radar installations extend China’s surveillance coverage across virtually the entire South China Sea. Fighter aircraft operating from the runways can intercept adversary reconnaissance flights. Surface-to-air missiles complicate any attempt to establish air superiority. Anti-ship cruise missiles threaten vessels transiting within range. Together, these capabilities create what military planners call an anti-access/area denial bubble: a zone where operating becomes costly, risky, and potentially suicidal.

The question is: denial for what purpose?

Taiwan’s Shadow

Every serious analysis of a Taiwan conflict identifies the same problem for China. The island sits 100 miles from the mainland across the Taiwan Strait—close enough to see on a clear day, far enough to require an amphibious assault of unprecedented complexity. The People’s Liberation Army would need to transport hundreds of thousands of troops and their equipment across contested waters, establish a beachhead against determined resistance, and sustain operations while under attack from Taiwanese, American, and likely Japanese forces.

The South China Sea bases solve none of these problems directly. They are 500 miles from Taiwan at their closest. No invasion force would stage from Fiery Cross Reef.

What the bases do is protect China’s southern flank.

In any Taiwan scenario, American submarines would hunt Chinese surface vessels throughout the Western Pacific. Carrier strike groups would seek to establish sea control. Aircraft from Guam, Japan, and potentially the Philippines would contest Chinese airspace. The South China Sea bases complicate all of these operations.

A submarine transiting from the Indian Ocean toward the Taiwan Strait must pass through waters now covered by Chinese sensors. A carrier group approaching from the south faces missile threats from multiple directions. Aircraft routing through the region encounter overlapping radar coverage that eliminates surprise. The bases do not win a Taiwan war. They raise the cost of American intervention.

This is the logic of the concrete. Every radar dome, every hardened aircraft shelter, every missile battery increases the price America must pay to defend Taiwan. The reputational costs Beijing incurs—the alienated neighbors, the strengthened alliances, the international condemnation—are not miscalculations. They are payments toward a specific strategic objective.

The Reputational Ledger

How severe are those costs? Less than the question implies.

China’s South China Sea militarization has certainly damaged relationships. The Philippines, once drifting toward accommodation with Beijing, now hosts American intermediate-range missiles in northern Luzon. Vietnam has quietly expanded defense cooperation with Washington. Japan has increased its naval presence in regional waters. Australia has committed to nuclear-powered submarines specifically designed for operations in contested seas.

Yet the damage has limits. No Southeast Asian nation has imposed meaningful sanctions on China. Trade flows continue unimpeded. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations remains paralyzed by consensus requirements and Cambodian obstruction. Even the Philippines, which won a landmark arbitration ruling against China in 2016, continues extensive economic engagement with Beijing.

The arbitration case is instructive. The Permanent Court of Arbitration ruled that “China’s historic rights claims over maritime areas within the nine-dash line have no lawful basis under UNCLOS.” Beijing declared the award “null and void” and ignored it entirely. The tribunal had no enforcement mechanism. China suffered embarrassment but no consequences.

Compare this to Russia’s experience after invading Ukraine. Moscow faces comprehensive sanctions, asset freezes, export controls, and near-total exclusion from Western financial systems. China’s South China Sea activities have produced nothing comparable. The reputational costs are real but manageable—diplomatic friction, not economic warfare.

Beijing has calculated, correctly so far, that the world will accept incremental territorial expansion more readily than sudden conquest. The artificial islands emerged over years, not days. Each dredging operation was small enough to avoid triggering decisive response. By the time the scale became apparent, the concrete had hardened.

This pattern—gradual fait accompli, calibrated to stay below response thresholds—may be the template for Taiwan.

The 2027 Question

American intelligence officials have testified that Xi Jinping instructed the PLA to be ready by 2027 to conduct a successful invasion of Taiwan. This date has acquired talismanic significance in Washington, treated as a countdown to war.

The reality is more nuanced. The 2027 deadline is a capability target, not an invasion order. Xi wants the option, not necessarily the action. The 20th Party Congress report reaffirmed that “resolving the Taiwan question and realizing China’s complete reunification is, for the Party, a historic mission and an unshakable commitment.” It avoided specifying a timeline.

But the South China Sea militarization reveals something about Beijing’s planning horizon that official statements obscure.

Building artificial islands takes years. Hardening them for military use takes more years. The infrastructure China has constructed represents decisions made a decade ago coming to fruition now. These are not impulsive gestures. They are investments in a specific future.

The investments continue. Recent activity focuses on “upgrading surveillance and weapons systems, surging coast guard and militia presence” rather than building new islands. The infrastructure is complete. Beijing is now optimizing it.

This suggests a planning cycle measured in decades, not years. China is not racing toward 2027. It is building capacity for a range of scenarios that might unfold over the next twenty years. Taiwan reunification by 2049—the centenary of the People’s Republic—appears in Party documents as an aspirational goal. The South China Sea bases will still be operational then.

The Temporal Trap

Here lies the deepest insight the reef militarization offers.

China operates on generational timescales. The “century of humiliation” narrative that shapes Chinese strategic culture refers to events from 1839 to 1949—a hundred-year arc of foreign domination that the Party claims to have ended. Reunification with Taiwan is framed as completing that historical redemption. The timeline is measured in decades because the grievance is measured in centuries.

American strategy operates on different rhythms. Administrations change every four to eight years. Defense budgets fluctuate with political cycles. Public attention shifts with news cycles. The “pivot to Asia” announced in 2011 has been renamed, reframed, and periodically forgotten multiple times since.

Taiwan exists in perpetual present. Its survival depends on deterrence that must be credible every single day. A successful invasion requires only one failure of that deterrence.

These temporal asymmetries create structural advantages for Beijing. China can wait for moments of American distraction—a crisis in Europe, domestic political turmoil, economic recession. It can probe continuously, testing responses, accumulating data about adversary capabilities and intentions. It can build infrastructure that compounds in value over time.

The South China Sea bases represent this temporal strategy made concrete. They were built during one American administration, expanded during another, and will threaten a third. Each year they exist, they become more integrated into Chinese military planning. Each year, the cost of removing them—militarily or diplomatically—increases.

What the Neighbors See

Southeast Asian nations watch this unfold with clear eyes and limited options.

Vietnam has the most direct stake. Hanoi claims many of the same features China has militarized and has conducted its own smaller-scale reclamation projects. Vietnamese defense spending has grown at 5.6% annually, a sustained investment in capabilities to resist Chinese pressure. But Vietnam shares a land border with China and depends on Chinese trade. It balances, but carefully.

The Philippines has shifted most dramatically. Under President Rodrigo Duterte, Manila pursued accommodation with Beijing, downplaying the arbitration victory and accepting Chinese investment. Under President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., the Philippines has embraced American security guarantees, expanded base access under the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement, and publicized Chinese coast guard harassment of Filipino vessels.

This shift matters because it demonstrates that Chinese pressure can backfire. The more aggressively Beijing’s coast guard operates—ramming vessels, deploying water cannons, blocking resupply missions to Philippine outposts—the more Manila moves toward Washington. Each incident generates viral footage that hardens Filipino public opinion against China.

Yet this dynamic has limits. The Philippines cannot expel China from the South China Sea. It can only raise the reputational cost of Chinese behavior and deepen American commitment. Whether that commitment would survive an actual conflict remains uncertain.

The Insurance Premium

Markets price risk more honestly than diplomats discuss it. Shipping insurance premiums for South China Sea transits have risen steadily as tensions increase. War-risk coverage, once a formality, now reflects genuine actuarial concern about conflict disruption.

This pricing mechanism reveals an uncomfortable truth. The global economy has already incorporated South China Sea instability into its calculations. Businesses route around risk. Supply chains adjust. The cost is diffuse—slightly higher prices, slightly longer shipping times, slightly larger insurance premiums—but it is real.

China pays a version of this cost too. Its own trade transits the same waters. Its energy imports flow through the same chokepoints. Militarizing the South China Sea does not give Beijing control over these flows; it gives Beijing the ability to threaten them. That threat is most valuable if never exercised.

This is the paradox of the artificial islands. Their military utility depends on their not being used militarily. In peacetime, they project power and complicate adversary planning. In wartime, they become targets—fixed, visible, and vulnerable to precision strikes. The billions of dollars in concrete and steel could be reduced to rubble in hours.

Beijing knows this. The bases are not fortresses. They are signals. They communicate resolve, capability, and willingness to accept costs. They tell Washington that any intervention in a Taiwan scenario will be expensive. They tell Taipei that help may not arrive in time. They tell Southeast Asian neighbors that accommodation is wiser than resistance.

The message has been received. Whether it has been believed is another matter.

The Path Not Taken

China had alternatives. It could have pursued its South China Sea claims through legal mechanisms, accepting the constraints of international law in exchange for legitimacy. It could have negotiated joint development agreements with rival claimants, sharing resources rather than monopolizing them. It could have left the reefs as they were—submerged features with disputed status—rather than transforming them into military installations that clarify the threat.

Beijing rejected these paths. The 2016 arbitration ruling, which might have been a face-saving off-ramp, was dismissed as illegitimate. Negotiations over a Code of Conduct with ASEAN have dragged for decades without conclusion. The reefs were dredged, the runways poured, the missiles installed.

This pattern of choices reveals strategic priorities. China values capability over legitimacy, control over cooperation, options over constraints. The South China Sea militarization is not an aberration. It is policy.

The same logic applies to Taiwan. Beijing prefers peaceful reunification but prepares for coercion. It seeks international acceptance but will proceed without it. It calculates costs but accepts them when the stakes are high enough.

The artificial islands are proof of concept. They demonstrate that China can absorb reputational damage, outlast international criticism, and create facts on the ground—or water—that reshape the strategic environment. If this works in the South China Sea, why not the Taiwan Strait?

What Comes Next

The trajectory is clear. China will continue upgrading its South China Sea installations, improving sensors, rotating aircraft, and exercising forces. It will continue gray-zone operations against Philippine vessels, calibrating pressure to stay below the threshold of armed conflict. It will continue military exercises around Taiwan, normalizing the presence of PLA forces in positions that could support a blockade or invasion.

American responses will continue too. Freedom of navigation operations will transit disputed waters. Alliance relationships will deepen. Military aid to Taiwan will flow. Diplomatic statements will condemn Chinese behavior.

Neither side will back down. Neither side will escalate to conflict. The competition will continue in the space between peace and war, each side probing for advantage, each side preparing for the moment when the other miscalculates.

The South China Sea bases will watch it all. Silent. Patient. Waiting.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Does China’s South China Sea militarization violate international law? A: Yes. The 2016 arbitration ruling found that China’s historic claims have no legal basis under UNCLOS, and the convention explicitly states that artificial islands cannot generate territorial waters or exclusive economic zones. China rejected the ruling and continues construction regardless, demonstrating that legal constraints mean little without enforcement mechanisms.

Q: Could the United States destroy China’s artificial islands in a conflict? A: Almost certainly. The islands are fixed targets with known positions, vulnerable to cruise missiles, precision-guided munitions, and submarine-launched weapons. Their military value lies in peacetime power projection and wartime complication of adversary operations, not survivability. Beijing has likely accepted that the bases would be early casualties in any major conflict.

Q: What does 2027 actually mean for Taiwan? A: The 2027 date represents a PLA capability milestone—the deadline Xi Jinping set for military readiness to conduct a successful Taiwan operation. It is not an invasion order or fixed timeline. Think of it as the moment China wants to have a credible option, not necessarily the moment it exercises that option.

Q: Why don’t Southeast Asian nations impose sanctions on China? A: Economic interdependence and limited leverage. China is the largest trading partner for most ASEAN states. Sanctions would hurt the sanctioning countries as much as China, and no Southeast Asian nation has the economic weight to impose meaningful costs unilaterally. Collective action is blocked by ASEAN’s consensus requirements and Chinese diplomatic pressure on individual members.

The Concrete Endures

In 1946, the Republic of China government—the same government now confined to Taiwan—first published a map showing eleven dashes enclosing most of the South China Sea as Chinese territory. The People’s Republic inherited the claim, reduced it to nine dashes, and spent decades doing nothing to enforce it.

Then came the dredgers. The concrete mixers. The construction crews working around the clock to transform submerged reefs into permanent military installations. What was once a line on a map became infrastructure. What was once a claim became a fact.

The artificial islands cannot be un-built. They cannot be wished away by arbitration rulings or diplomatic protests. They exist, and their existence changes calculations in Beijing, Washington, Taipei, and every capital that depends on the sea lanes they overlook.

This is what the concrete reveals about Beijing’s Taiwan timeline: not a date, but a method. Patient accumulation of capability. Gradual normalization of presence. Incremental expansion of control. The willingness to accept costs today for options tomorrow.

The reefs took a decade to build. Taiwan has been waiting seventy-five years. Beijing is in no hurry. The concrete endures.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative Island Tracker - Comprehensive documentation of Chinese artificial island construction and militarization

- China’s Statement on the 2016 Arbitration - Beijing’s official rejection of the tribunal ruling

- 20th Party Congress Work Report - Xi Jinping’s statement on Taiwan reunification as “historic mission”

- CSIS Analysis of Beijing’s Taiwan Timeline - Expert assessment of Party Congress language on unification deadlines

- War on the Rocks on Fait Accompli Strategy - Analysis of gradual territorial expansion tactics

- Jamestown Foundation on Taiwan’s Spratly Initiative - Historical context on ROC claims predating PRC