Why China keeps building in the South China Sea despite already controlling it

Antelope Reef is not redundant expansion but the missing node in a surveillance network stretching from Hainan to the Spratlys. Beijing has learned that international protest is survivable—and strategic gaps are not.

🎧 Listen to this article

The Logic of Layered Control

China already dominates the South China Sea’s southern reaches. Its seven artificial islands in the Spratly archipelago bristle with airstrips, radar arrays, and missile batteries. Fiery Cross Reef alone hosts a 3,000-meter runway capable of handling any aircraft in Beijing’s inventory. So why risk fresh diplomatic friction by dredging Antelope Reef, a submerged coral formation 600 kilometers to the north in the Paracels?

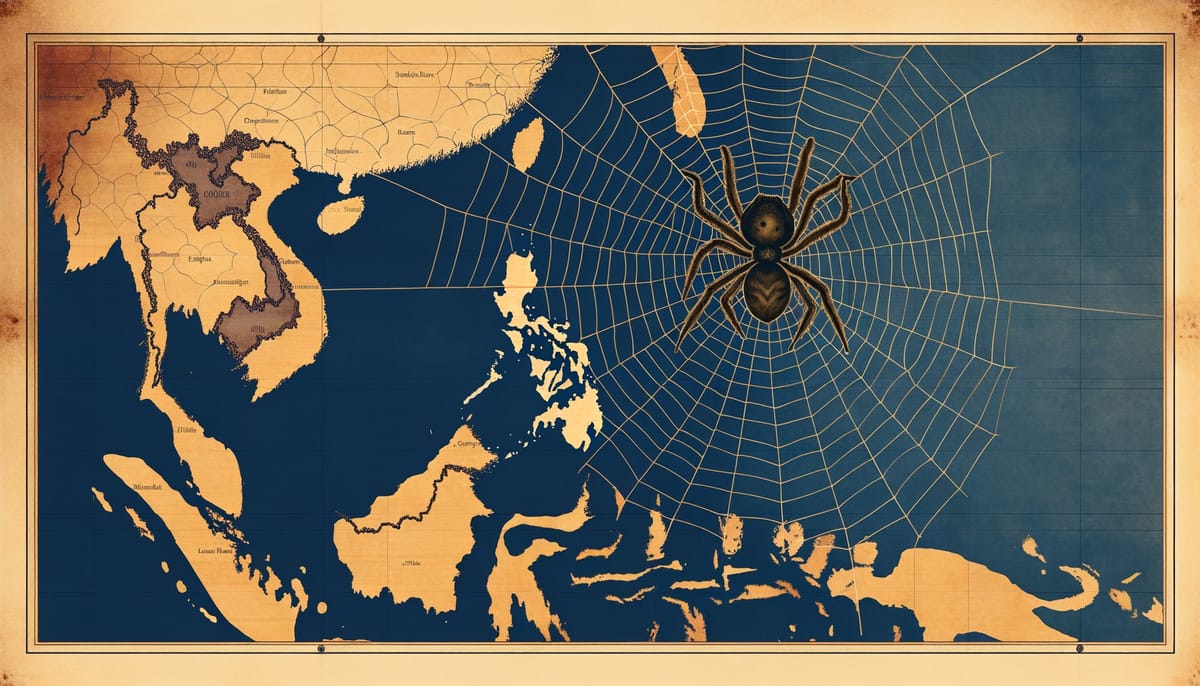

The answer lies not in what China lacks, but in what it is building: a layered defensive architecture designed to transform the entire South China Sea into a controlled space. Antelope Reef is not redundant. It is the missing node in a surveillance and denial network stretching from Hainan Island to the southern Spratlys—a network that cannot function with gaps.

Two Archipelagos, One Strategy

The Spratlys and Paracels serve fundamentally different strategic purposes, though Western analysis often conflates them. The Spratlys project power southward, threatening shipping lanes and providing forward bases for operations toward the Philippines, Malaysia, and Indonesia. The Paracels protect the homeland.

Hainan Island houses China’s most sensitive military assets. The Yulin Naval Base on its southern coast shelters the Jin-class nuclear ballistic missile submarines that constitute China’s sea-based nuclear deterrent. These submarines must transit through the South China Sea to reach patrol areas where their missiles can threaten adversary territory. Every improvement to Paracel infrastructure shortens their exposure time and complicates hostile detection efforts.

Antelope Reef sits at coordinates that matter: 16°27‘45”N, 111°35‘20”E, roughly 300 kilometers southeast of Hainan. This positions it to fill a surveillance gap between China’s existing Paracel outposts and the mainland. High-frequency radar systems have limited surface horizons. Networking multiple islands and reefs creates what defense planners call a “unified surveillance manifold”—continuous coverage where previously there were blind spots.

The Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative documents that Antelope Reef, known as Linyang Jiao in Chinese, currently hosts a small outpost on an otherwise submerged feature. Expansion would likely add helipads, berthing facilities, and electronic warfare systems. These are not offensive weapons. They are the sensors and nodes that make offensive weapons effective.

The Geometry of Denial

China’s South China Sea strategy operates on a principle borrowed from ancient fortress design: defense in depth. An attacker must breach multiple lines before reaching anything vital. Each line imposes costs, consumes munitions, and reveals intentions.

The first line runs through the Spratlys. Any naval force approaching from the south encounters radar coverage, potential missile threats, and the certainty of detection hundreds of kilometers before reaching Chinese waters. The second line runs through the Paracels. Forces that penetrate the southern defenses face fresh obstacles. The third line is Hainan itself, with its airfields, submarine pens, and shore-based missiles.

Antelope Reef strengthens the second line. Without it, there exists a corridor of reduced surveillance between the northern Paracels and Hainan—not a gap large enough to exploit easily, but large enough to worry planners who think in worst-case scenarios. Chinese military doctrine, shaped by the “century of humiliation” when foreign powers exploited every weakness, treats such gaps as unacceptable.

The CSIS analysis of China’s island-building notes that since 2013, China has created over 3,200 acres of new land across the South China Sea. This is not opportunistic expansion. It follows a coherent logic: fill every gap, eliminate every blind spot, ensure that no adversary can approach undetected.

Why International Backlash Is Acceptable

China’s calculation on Antelope Reef reflects a clear-eyed assessment: the costs of international protest are manageable, while the costs of strategic vulnerability are not.

Consider what “backlash” actually means in practice. The Philippines has filed nearly 200 diplomatic protests under President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. Vietnam issues regular condemnations. The United States conducts freedom of navigation operations. In 2020, Washington imposed targeted sanctions on 24 Chinese companies linked to artificial island construction. These are irritants, not deterrents.

The 2016 Hague Tribunal ruling illustrates the dynamic perfectly. The Permanent Court of Arbitration ruled overwhelmingly against China, finding that Beijing had violated international law, caused “irreparable harm” to the marine environment, and had no legal basis for its expansive claims. China declared the ruling “null and void” and continued building. The international community protested. Nothing changed.

This pattern—protest without consequence—has taught Beijing that rhetorical costs are bearable. The real question is whether any action could impose costs severe enough to alter Chinese behavior. Trade sanctions affecting major Chinese industries might qualify. Military confrontation certainly would. But no state has shown willingness to escalate to either level over reef construction.

The asymmetry is structural. For China, the South China Sea touches core interests: territorial integrity, regime legitimacy, military security. For other states, it represents important but not existential concerns. This mismatch in stakes produces predictable outcomes. China acts; others protest; China continues.

The Domestic Audience

International audiences are not the only ones watching. Xi Jinping’s domestic legitimacy rests partly on demonstrating that China can assert its historical claims against foreign opposition.

The Chinese government’s 2016 statement on the South China Sea frames these waters in civilizational terms: “The activities of the Chinese people in the South China Sea date back to over 2,000 years ago.” This is not merely diplomatic rhetoric. It reflects a narrative of national rejuvenation central to Communist Party legitimacy—the story that China, after a century of weakness and humiliation, is finally reclaiming its rightful position.

Every new outpost validates this narrative. Every successful defiance of international criticism demonstrates that China can no longer be pushed around. The domestic political value of continued construction may exceed its military value, though both are substantial.

Hainan itself embodies this dual logic. The island functions simultaneously as a military bastion and a tourism destination marketed as “China’s Hawaii.” CNN reports on its development as a vacation hotspot, while Global Times emphasizes that “Hainan’s island idyll needs military guard.” The South China Sea must be both playground and fortress, and Antelope Reef serves both functions by extending the protective perimeter.

Legal Architecture and Its Limits

The international legal framework governing maritime claims was not designed for artificial islands. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) grants coastal states 12-nautical-mile territorial seas around “naturally formed” land features and 200-nautical-mile exclusive economic zones around features that can “sustain human habitation.” It says nothing about features that are created rather than found.

The 2016 tribunal addressed this gap by ruling that artificial modifications cannot change a feature’s legal status. A submerged reef remains a submerged reef regardless of what is built upon it. China rejected this interpretation and has continued acting as though construction creates legal rights.

This creates a peculiar situation. Under international law as interpreted by the tribunal, Antelope Reef generates no maritime entitlements. Under Chinese law and practice, it anchors claims to surrounding waters. The two legal systems operate in parallel, each internally consistent, neither acknowledging the other.

Beijing’s approach reflects a broader strategy: establish facts on the ground (or water) that eventually become normalized. The Congressional Research Service notes that UNCLOS provides frameworks but limited enforcement mechanisms. A state willing to absorb diplomatic costs can simply ignore unfavorable rulings. Over time, the status quo shifts.

The Temporal Dimension

The timing of renewed activity at Antelope Reef is not accidental. China and ASEAN nations have been negotiating a Code of Conduct for the South China Sea for over two decades. A target date of 2026 has been discussed. The Philippines assumes the ASEAN chairmanship that year.

Building now accomplishes several objectives. It establishes facts before any agreement might constrain future construction. It tests whether negotiations are serious or merely diplomatic theater. It signals that China will not accept limitations on what it considers sovereign territory regardless of what documents are signed.

This temporal logic—act now, negotiate later—has characterized Chinese behavior throughout the island-building campaign. The massive Spratly construction of 2013-2016 preceded and arguably rendered moot subsequent diplomatic discussions. Antelope Reef follows the same pattern.

The approach reflects different time horizons. Democratic governments operate on electoral cycles, rarely planning beyond the next election. Chinese strategic culture, shaped by millennia of imperial history, thinks in generations. What matters is not next year’s headlines but the map in 2050.

What Changes and What Doesn’t

Antelope Reef will not alter the military balance in the South China Sea. China already possesses overwhelming local superiority. No additional radar station or helipad changes that fundamental reality.

What it does change is the completeness of Chinese control. The surveillance network becomes denser. The response time to incursions shortens. The psychological message to regional states intensifies: there is no corner of these waters beyond Beijing’s reach.

For Vietnam, which claims the Paracels as its own, the development is particularly pointed. Hanoi calls Antelope Reef “Da Hai Sam”—Sea Cucumber Rock—and considers Chinese presence there illegal. But Vietnam lacks the capability to contest Chinese construction and the allies to do so on its behalf. Protest is its only option.

The United States faces a different calculation. Freedom of navigation operations demonstrate that Washington does not accept Chinese claims, but they do not prevent Chinese construction. The gap between symbolic assertion and practical effect grows wider with each new outpost.

The Stakes Ahead

If current dynamics continue, the South China Sea will become functionally Chinese by mid-century—not through formal annexation, which would trigger responses Beijing wishes to avoid, but through the accumulation of infrastructure, the normalization of control, and the exhaustion of opposing will.

This trajectory is not inevitable. It could be altered by sustained multilateral pressure, by credible military deterrence, or by internal Chinese reassessment. None of these appears likely in the near term.

The multilateral option founders on collective action problems. ASEAN states have competing interests and varying relationships with Beijing. No coalition has formed capable of imposing costs that exceed China’s tolerance for pain.

The military option risks escalation that no party wants. The United States maintains forces capable of challenging Chinese control, but employing them over reef construction would represent a dramatic escalation from current policy. Deterrence works against invasion; it works less well against gradual construction.

Internal reassessment would require Chinese leaders to conclude that the costs of continued expansion exceed the benefits. Nothing in current international responses suggests this conclusion is imminent.

FAQ: Key Questions Answered

Q: Does building artificial islands give China legal rights to surrounding waters? A: Under the 2016 Hague Tribunal ruling, no. Artificial modifications cannot change a feature’s legal status under UNCLOS. However, China rejected this ruling and continues acting as though construction creates entitlements. The practical effect depends on enforcement, which has been minimal.

Q: Why doesn’t the United States stop Chinese island-building? A: Military action over reef construction would represent a dramatic escalation that could trigger broader conflict. Freedom of navigation operations demonstrate non-acceptance of Chinese claims but do not prevent construction. The gap between symbolic protest and physical prevention reflects the asymmetry in stakes between the parties.

Q: How many countries claim territory in the South China Sea? A: Six governments maintain claims: China, Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, and Taiwan. Vietnam occupies the most features (48), while China has built the most extensive infrastructure on its seven Spratly outposts. The Paracels are contested primarily between China and Vietnam.

Q: What would change China’s behavior in the South China Sea? A: Costs that exceed benefits. Current diplomatic protests impose reputational costs that Beijing considers acceptable. Significant economic sanctions affecting major industries or credible military deterrence might alter the calculation, but neither has been deployed over island construction.

The Quiet Accumulation

Antelope Reef will not make headlines the way a military confrontation would. Its significance lies precisely in its mundanity—another outpost, another protest, another step in a process that has continued for over a decade.

This is how control is established in the modern era: not through dramatic conquest but through patient accumulation. Each new feature makes the next one easier. Each unanswered construction project lowers the threshold for the next. The map changes slowly, then suddenly.

China is not building Antelope Reef despite controlling the Spratlys. It is building Antelope Reef because controlling the Spratlys taught Beijing that it can. The lesson of the past decade is that international backlash is survivable, legal rulings are ignorable, and facts on the water eventually become the new normal.

The question is not why China risks backlash. The question is why it wouldn’t, given everything that has come before.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative - Antelope Reef - Primary documentation of the reef’s current status and Chinese presence

- China Power Project - South China Sea Trade - Analysis of Chinese military infrastructure and regional claims

- China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs Statement - Official Chinese government position on South China Sea claims

- Congressional Research Service - Maritime Claims - UNCLOS framework and legal analysis

- CNN - Hainan Island Explainer - Background on Hainan’s strategic and economic significance

- AMTI Island Tracker - China - Comprehensive tracking of Chinese island-building activities

- Global Times - Hainan Military Analysis - Chinese perspective on Hainan’s security requirements