Why Britain traded sovereignty for security at Diego Garcia

The UK-Mauritius deal on the Chagos Archipelago looks like retreat. It is actually a strategic consolidation—trading the fiction of colonial ownership for a 99-year lease that secures one of the world's most important military bases against legal challenges that were becoming impossible to ignore.

🎧 Listen to this article

The Lease That Binds

Britain has not surrendered Diego Garcia. It has traded the fiction of ownership for the reality of control. On May 22, 2025, Foreign Secretary David Lammy signed a treaty that hands sovereignty of the Chagos Archipelago to Mauritius while securing a 99-year lease on the atoll that houses one of the world’s most important military installations. The deal resolves a legal embarrassment that had festered since 2019, when the International Court of Justice ruled Britain’s continued administration unlawful. It does not resolve the strategic anxiety that prompted the question in the first place: whether Britain, in settling an old colonial debt, has handed China an opportunity in the Indian Ocean.

The anxiety is understandable but misplaced. It confuses sovereignty with capability, and capability with access. Diego Garcia’s value to Western strategy lies not in the Union Jack that flies above it, but in the runways, fuel depots, and deep-water berths that make it irreplaceable for projecting power across three continents. Those assets remain under British operational control, with American forces guaranteed unrestricted use. What has changed is the nameplate on the door. What has not changed is who holds the keys.

The Legal Trap Britain Could Not Escape

The Chagos dispute was never really about Diego Garcia. It was about decolonization—and Britain’s failure to complete it cleanly. When London detached the archipelago from Mauritius in 1965, three years before granting independence, it created a constitutional wound that refused to heal. Mauritius never accepted the separation. The displaced Chagossians never stopped demanding return. And the international legal system, which had largely ignored the issue for decades, eventually delivered a verdict Britain could not ignore.

The ICJ’s 2019 advisory opinion was non-binding in the formal sense. It was devastating in every other sense. By thirteen votes to one, the court found that Britain’s administration of Chagos was unlawful and must end “as rapidly as possible.” Three months later, the UN General Assembly endorsed the ruling by 116 votes to six. Britain found itself in the company of the United States, Australia, Hungary, Israel, and the Maldives—an awkward coalition of the willing to be embarrassed.

The vote triggered what political scientists call a preference falsification cascade. States that had privately tolerated the Anglo-American presence in the Indian Ocean discovered they could no longer publicly defend it. The reputational costs of supporting Britain exceeded the strategic benefits of maintaining silence. One by one, governments that had abstained on earlier resolutions shifted to supporting Mauritius. The bandwagon rolled forward. Britain’s position became untenable not because the law compelled compliance, but because the politics made resistance too expensive.

This is the context that critics of the Chagos deal consistently omit. The choice facing Keir Starmer’s government was not between keeping Diego Garcia and giving it away. It was between negotiating a controlled transition that preserved operational access or watching the legal noose tighten until the base’s legitimacy collapsed entirely. The treaty signed in May 2025 represents the former. The alternative was not the status quo. The alternative was worse.

What the Treaty Actually Says

The UK-Mauritius agreement runs to 34 pages of careful legal architecture. Its essential structure is simple: Mauritius gains sovereignty over the entire archipelago, including Diego Garcia. Britain retains authority to “exercise the sovereign rights and authorities of Mauritius required to ensure the continued operation of the Base” for an initial period of 99 years, with provisions for extension. The United States, whose forces constitute the bulk of Diego Garcia’s military presence, endorsed the arrangement within hours.

The strategic implications require parsing. Sovereignty and operational control are not the same thing. Under the treaty, British and American personnel retain exclusive access to Diego Garcia. Mauritius cannot station forces there. Third parties cannot use the base without British and American consent. The operational perimeter remains exactly what it was before the signatures dried.

What Mauritius gains is everything else: the symbolism of decolonization fulfilled, the economic benefits of the outer islands, the diplomatic prestige of having prevailed against a former colonial power. What Britain gains is legal clarity. The base that was vulnerable to challenge is now protected by treaty. The arrangement that depended on contested sovereignty now rests on explicit consent.

Critics argue this creates new vulnerabilities. If Mauritius can grant a lease, Mauritius can revoke one. If sovereignty resides in Port Louis, future governments might extract concessions, invite Chinese investment, or simply refuse to extend the agreement when it expires in 2124. These concerns are not frivolous. They are also not unique to this arrangement. Every overseas military installation in the world depends on host-nation consent. Diego Garcia is no different—it simply made the dependency explicit.

The China Question

The strategic anxiety surrounding the Chagos deal crystallizes around a single fear: that China will exploit the transition to establish its own presence in the Indian Ocean. The fear is not irrational. China’s “String of Pearls” strategy—the network of ports and facilities stretching from the South China Sea to the Horn of Africa—represents a systematic effort to secure sea lines of communication and project power into waters historically dominated by Western navies. Djibouti hosts China’s first overseas military base. Gwadar in Pakistan and Hambantota in Sri Lanka serve dual commercial and strategic purposes. Why wouldn’t Beijing try to add Chagos to the string?

The answer lies in the treaty’s fine print. The agreement explicitly prohibits Mauritius from permitting any third party to establish military or dual-use facilities on the archipelago. Chinese naval vessels cannot call at the outer islands without British and American approval. The marine protected area that Britain controversially established in 2010—and which an arbitral tribunal later found violated Mauritius’s rights—will now be administered jointly, creating an additional layer of oversight.

More fundamentally, the China threat to Diego Garcia was always overstated. The atoll’s value lies in its isolation. It sits more than a thousand miles from the nearest significant landmass, surrounded by deep water that makes submarine operations exceptionally difficult to detect. China could build a dozen ports on the Indian Ocean littoral without replicating what Diego Garcia provides: a platform beyond the reach of land-based missiles, secure from the surveillance that blankets continental coastlines, capable of supporting operations from the Persian Gulf to the Strait of Malacca.

This is not to dismiss China’s Indian Ocean ambitions. The Jamestown Foundation’s analysis of Chinese naval strategy identifies the pursuit of “strategic strongpoints” as a core element of Beijing’s maritime expansion. Research published by the China Maritime Studies Institute documents how Djibouti has evolved from a logistics facility into a genuine military installation capable of supporting combat operations. The pattern is clear: China is building the infrastructure for sustained naval presence far from home.

But Diego Garcia does not fit the pattern. China’s strongpoints share common characteristics: proximity to commercial shipping routes, dual-use potential that blurs military and civilian functions, host governments willing to accept Chinese investment and influence. Mauritius offers none of these advantages for a Chinese base in Chagos. The outer islands lack the infrastructure to support significant military operations. The treaty prohibits their militarization. And Mauritius itself, while maintaining cordial relations with Beijing, has strong incentives to preserve its relationships with India, Britain, and the United States.

The Real Strategic Calculation

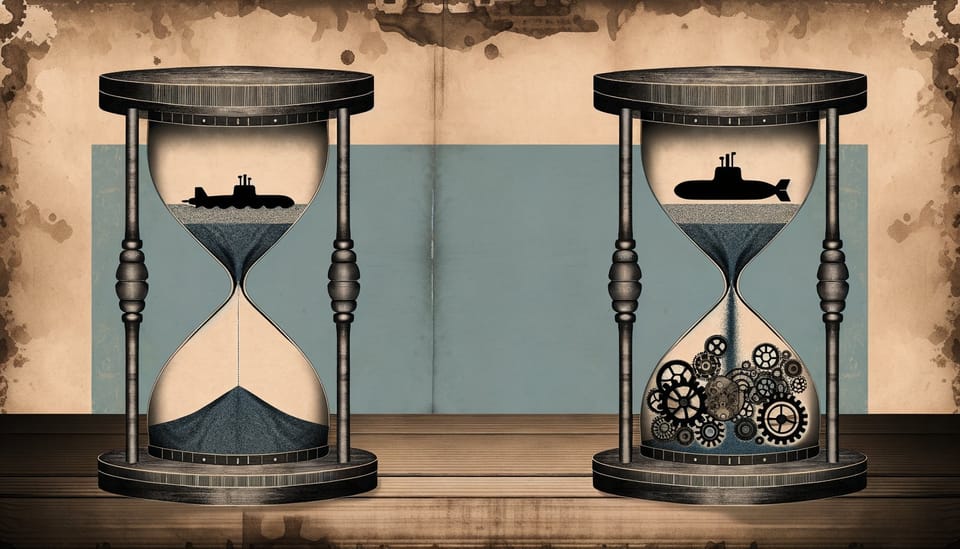

The Chagos deal makes sense only when viewed through the lens of what strategists call “temporal incommensurability”—the problem of actors operating on fundamentally different time horizons. Britain faced a legal position that was deteriorating by the year. Each UN vote, each court ruling, each diplomatic defection made the status quo harder to sustain. The question was not whether to negotiate, but when—and on what terms.

By moving in 2025, the Starmer government secured arrangements that a future negotiation might not have achieved. The 99-year lease provides operational certainty through 2124. The prohibition on third-party military use addresses the China concern directly. The financial terms—Britain will make annual payments to Mauritius, the exact figures undisclosed—represent a cost of doing business, not a strategic concession.

The alternative scenarios are instructive. Had Britain refused to negotiate, the legal pressure would have continued. The UN General Assembly might have moved from advisory resolutions to binding measures. States hosting British military facilities might have faced pressure to reconsider their own arrangements. The “rules-based international order” that Britain claims to champion would have been exposed as a convenience, applicable only when it served British interests.

As the Lowy Institute observed, India’s attitude toward Diego Garcia has shifted dramatically in recent years. Where New Delhi once viewed the American presence with suspicion—a Cold War relic that threatened Indian Ocean autonomy—it now sees the base as a counterweight to Chinese expansion. This shift reflects India’s own strategic reorientation, but it also reflects the legitimacy that a negotiated settlement provides. A base that exists by treaty is harder to criticize than a base that exists by colonial fiat.

The Domestic Politics of Imperial Retreat

Within Britain, the Chagos deal has become a proxy for larger anxieties about national decline. Conservative critics frame it as surrender, a Labour government trading away strategic assets to satisfy progressive pieties about decolonization. The comparison to the Falklands and Gibraltar is inevitable and instructive.

The cases are not analogous. The Falklands and Gibraltar have resident populations that have repeatedly expressed their desire to remain British. The Chagos Archipelago’s original inhabitants were forcibly removed to make way for the military base—a historical crime that undermines any claim to democratic legitimacy. As the Guardian noted, the legal and moral foundations of British sovereignty in each case are fundamentally different.

Starmer has been explicit about this distinction. The Falklands and Gibraltar will remain British, he has pledged, because their populations wish it. Chagos returns to Mauritius because international law demands it and because the alternative—maintaining a colonial possession against the will of the international community—contradicts Britain’s stated values.

The political risk is real nonetheless. Donald Trump’s criticism of the deal, delivered with characteristic bluntness, resonated with those who see any territorial concession as weakness. The parliamentary debates revealed deep unease among some Labour MPs about the precedent being set. And the Chagossian community itself—whose views were documented in parliamentary evidence—remains divided about a settlement that restores Mauritian sovereignty without guaranteeing their own right of return.

The Mauritius Factor

The deal’s long-term stability depends on Mauritius remaining a reliable partner. This is where the China anxiety finds its most legitimate expression. Mauritius has signed a free trade agreement with Beijing. Chinese investment in the island nation has grown steadily. The Belt and Road Initiative offers infrastructure financing that Western governments cannot match. If Mauritius drifts into China’s orbit, the treaty’s prohibitions on third-party military use might prove less durable than they appear.

The concern is valid but overstated. Mauritius is not a client state waiting to be captured. It is a functioning democracy with strong institutions, a diversified economy, and relationships across the major power blocs. Its strategic value lies precisely in its ability to balance competing interests—extracting benefits from China, India, Britain, and the United States without becoming dependent on any single patron.

The Chagos deal reflects this balancing act. Mauritius gains sovereignty, economic benefits, and diplomatic prestige. It also gains a stake in the base’s continued operation. The annual payments from Britain create a revenue stream that depends on the lease remaining in force. The prohibition on third-party military use protects Mauritius from becoming a pawn in great-power competition. The arrangement serves Mauritian interests not despite the Western military presence, but because of it.

This is the dynamic that China hawks consistently miss. Small states are not passive objects to be won or lost. They are strategic actors pursuing their own interests. Mauritius chose to negotiate with Britain rather than waiting for the legal process to deliver a more complete victory. It chose treaty obligations over theoretical freedom of action. These choices reflect a calculation that partnership with the West serves Mauritian interests better than alignment with China.

What Actually Changes

The operational impact of the Chagos deal is minimal. Diego Garcia will continue to host B-52 bombers capable of reaching targets across the Middle East and South Asia. It will continue to support nuclear submarines that patrol the Indian Ocean. It will continue to provide the logistical backbone for American power projection in a region that stretches from the Strait of Hormuz to the Malacca Strait.

What changes is the political foundation. The base that existed on contested legal ground now exists by explicit agreement. The sovereignty that was asserted unilaterally is now exercised by delegation. The colonial arrangement that embarrassed Britain at the United Nations has been replaced by a treaty that other states can accept.

This matters more than critics acknowledge. Military installations depend on political legitimacy. A base that the host government actively supports is more secure than one it merely tolerates. A presence that conforms to international law is harder to challenge than one that defies it. By resolving the Chagos dispute, Britain has strengthened the legal foundation of Diego Garcia even as it relinquished formal sovereignty.

The parallel to other basing arrangements is instructive. American forces in Japan operate under a Status of Forces Agreement that Japanese governments have periodically sought to renegotiate. American forces in Germany depend on a host nation that has grown increasingly ambivalent about the relationship. Every overseas military presence involves a trade-off between operational control and political sustainability. Diego Garcia is no exception. The Chagos deal simply made the trade-off explicit.

FAQ: Key Questions Answered

Q: Does the UK-Mauritius agreement affect US military operations at Diego Garcia? A: No. The US State Department confirmed that the agreement “secures the long-term, stable, and effective operation of the joint U.S.-UK military facility.” American forces retain unrestricted access under the same terms as before.

Q: Can China now build a military base in the Chagos Archipelago? A: The treaty explicitly prohibits Mauritius from permitting third-party military or dual-use facilities anywhere in the archipelago. Chinese military presence would require British and American consent, which will not be forthcoming.

Q: Will the Chagossians be allowed to return to Diego Garcia? A: The treaty permits Chagossian resettlement on the outer islands of the archipelago, but not on Diego Garcia itself, which remains under exclusive British operational control for the duration of the 99-year lease.

Q: Does this set a precedent for Gibraltar or the Falklands? A: The UK government insists it does not. Unlike Chagos, both Gibraltar and the Falklands have resident populations that have voted to remain British. The legal and political circumstances are fundamentally different.

The Long Game

Britain has not surrendered Diego Garcia’s strategic value. It has preserved that value by adapting to legal and political realities that could not be indefinitely ignored. The deal is imperfect. It creates dependencies that did not exist before. It requires trust in a Mauritian government that future elections might change. It costs money that could have been spent elsewhere.

But the alternative was not a cost-free status quo. The alternative was a legal position that grew weaker by the year, a diplomatic embarrassment that undermined Britain’s broader interests, and a base whose legitimacy depended on the willingness of other states to look the other way. That willingness was exhausted. The Chagos deal reflects the exhaustion.

China will continue to expand its Indian Ocean presence. It will build more ports, sign more agreements, cultivate more relationships with littoral states. This expansion is a challenge that Diego Garcia alone cannot address. It requires sustained investment in naval capabilities, diplomatic engagement with regional partners, and economic alternatives to Chinese infrastructure financing. The Chagos deal neither advances nor retards these efforts. It simply removes a distraction.

The base remains. The runways remain. The fuel depots and communications facilities and deep-water berths remain. What has changed is the story Britain tells about why they are there. The old story—colonial possession, strategic necessity, legal ambiguity—no longer served. The new story—negotiated agreement, mutual benefit, international legitimacy—may prove more durable. In the long competition for influence in the Indian Ocean, legitimacy is a strategic asset too.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- UK-Mauritius Agreement on the Chagos Archipelago - Full text of the May 2025 treaty establishing the legal framework for Diego Garcia

- US State Department Statement on UK-Mauritius Agreement - Official American endorsement of the deal

- ICJ Advisory Opinion on Chagos - The 2019 ruling that found British administration unlawful

- Jamestown Foundation: Strategic Strong Points and Chinese Naval Strategy - Analysis of China’s overseas basing ambitions

- China Maritime Studies Institute: Djibouti Report - Detailed assessment of China’s first overseas military base

- Lowy Institute: India’s Historic Shift on Diego Garcia - How Indian strategic thinking has evolved

- Parliamentary Evidence: Chagossian Views - Testimony from displaced islanders

- CNA Report: Diego Garcia Basing Rights - Strategic assessment of the base’s importance