Why Bougainville rejected Chinese mining investment—and what it reveals about Beijing's Pacific limits

When Bougainville's president turned away China Molybdenum Company in January 2026, he wasn't bowing to Western pressure. He was honoring a governance architecture forged in civil war—one that Beijing's economic instruments cannot penetrate.

The Mine That Stayed Closed

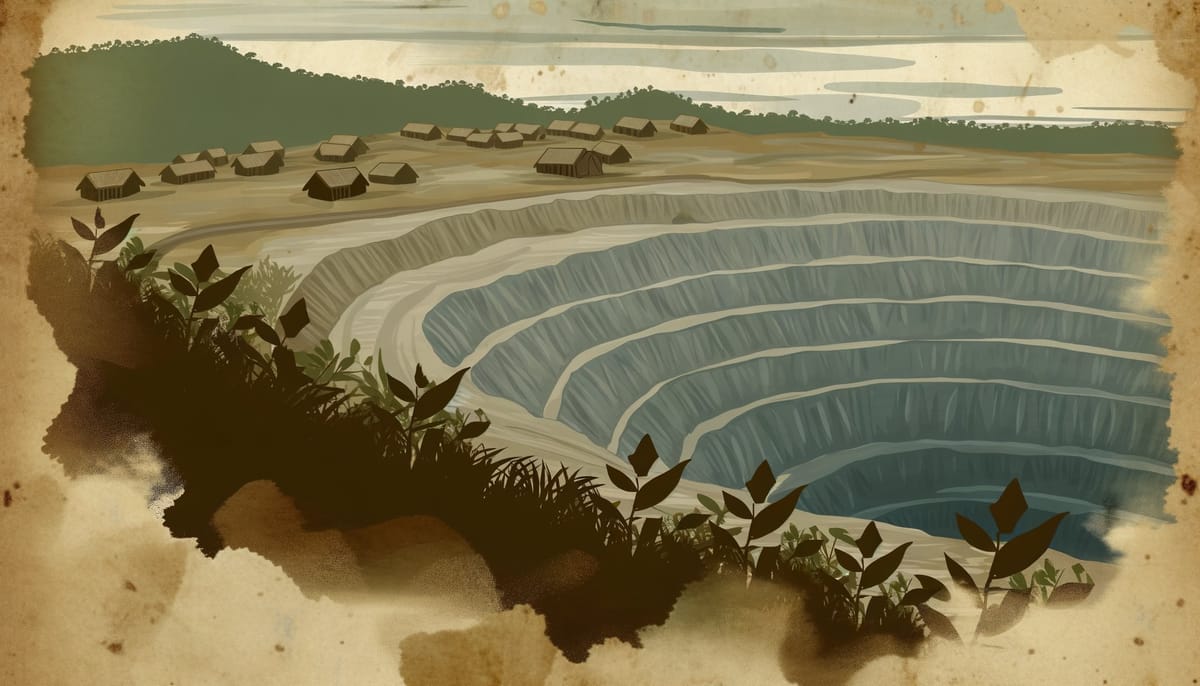

In January 2026, Bougainville’s President Ishmael Toroama rejected what looked like his archipelago’s best chance at independence. China Molybdenum Company had offered to partner with Bougainville Copper Limited to reopen the Panguna mine—a copper and gold deposit containing an estimated 5.3 million tonnes of copper and 547 tonnes of gold. The revenues could have funded the state-building that Papua New Guinea demands before recognizing Bougainville’s sovereignty. Toroama said no.

The refusal baffled observers who see Pacific Island nations as pawns in great-power competition, easily swayed by Beijing’s chequebook. Here was an impoverished proto-state, generating just 5.3% of its budget internally, turning away billions in potential investment. The conventional interpretation—that Australia and America pressured Bougainville to reject Chinese money—misses something fundamental. Toroama’s decision emerged from a political economy that Beijing’s economic instruments cannot easily penetrate.

Sovereignty’s Price Tag

Bougainville exists in a peculiar limbo. Its 2019 independence referendum delivered a 97.7% vote for separation from Papua New Guinea. But independence requires PNG’s parliament to ratify the result, and Port Moresby has made clear that fiscal self-sufficiency is a precondition. The Autonomous Bougainville Government has set 2027 as its target date. The arithmetic is brutal: Bougainville currently funds only a fraction of its expenditure. Independence without Panguna revenues looks like statehood without a state.

This creates what economists call a time-inconsistency problem. Toroama needs money now to prove Bougainville can function independently. But the source of that money matters for whether independence, once achieved, proves sustainable. A Chinese mining partner would deliver faster revenues—CMOC has demonstrated aggressive timelines in the Democratic Republic of Congo and elsewhere. Yet speed comes with strings that Bougainville’s legal architecture was specifically designed to prevent.

The Bougainville Mining Act 2015 represents a radical departure from conventional resource governance. It grants customary landowners ownership of minerals on their land and veto power over exploration or mining licenses. The ABG regulates but does not own. This structure emerged directly from the civil war that killed between 10,000 and 20,000 people from 1988 to 1998—a conflict triggered by Panguna’s environmental devastation and the colonial-era agreements that excluded landowners from meaningful participation.

The Act creates what one analyst called a “compliance abyss” for foreign investors. Before any exploration can proceed, companies must secure Land Access and Compensation Agreements from customary landowners. These landowners operate under matrilineal systems where senior women hold de facto authority over land decisions. The formal negotiations that Chinese state-owned enterprises excel at—government-to-government deals, sovereign guarantees, bilateral investment treaty protections—dissolve when they encounter a governance structure that distributes veto power across hundreds of clan groups.

The Memory That Won’t Fade

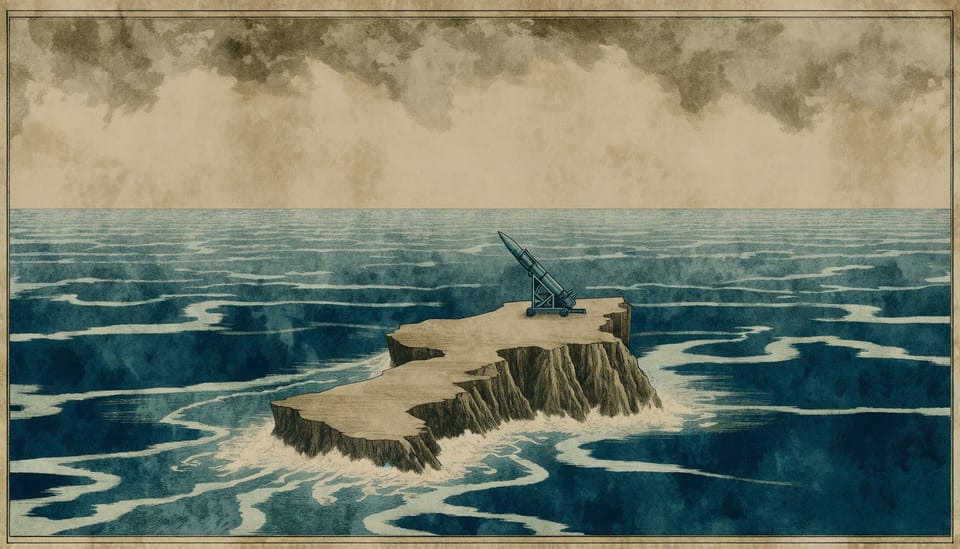

Panguna’s pit remains one of the world’s largest human-made holes. The Jaba River still runs with contamination from tailings that were dumped directly into the watershed for seventeen years. Rio Tinto’s subsidiary operated the mine under a 1967 agreement negotiated before Bougainville had any voice in its own affairs. When the company departed in 1989, it left behind environmental destruction that no compensation package has addressed.

This history is not abstract for Bougainvilleans. Toroama himself joined the Bougainville Revolutionary Army at nineteen, rose to field commander, was wounded by a rocket-propelled grenade, and eventually signed the 2001 peace agreement as BRA chief of defense. His political base includes ex-combatants who view foreign mining companies with visceral distrust. When Toroama stated that “with a Chinese company there is a risk of what it will bring to regional stability,” he was speaking to an audience that remembers what the last foreign miner brought.

The rejection of CMOC cannot be separated from this institutional memory. As the Berghof Foundation documented, Bougainville’s post-conflict governance deliberately embedded landowner authority to prevent any repetition of the colonial extraction model. The Mining Act’s requirement for customary consent is not a bureaucratic hurdle to be navigated—it is the central political settlement that ended the war.

Beijing’s economic coercion toolkit works through state-level leverage: debt obligations, infrastructure dependencies, trade relationships that can be weaponized. But Bougainville’s legal architecture routes critical decisions through clan structures that exist below the level where such leverage operates. A Chinese company might secure ABG approval and still face years of negotiation with landowner groups whose consent cannot be purchased at the sovereign level.

The Regional Calculus

Toroama explicitly connected his decision to Solomon Islands, Bougainville’s neighbor to the southeast. The 2022 security pact between Honiara and Beijing demonstrated how quickly Chinese engagement can shift regional dynamics. Bougainville sits at a strategic chokepoint—its waters control access between the Solomon Sea and the Pacific. A Chinese mining presence would bring not just investment but infrastructure, personnel, and the kind of economic entanglement that has proven difficult to unwind elsewhere in the Pacific.

Australia’s Pacific Step-Up and America’s Pacific Partnership have created an alternative architecture of support that Bougainville can access without accepting Chinese investment. The Lowy Institute’s analysis of Pacific influence dynamics suggests that smaller nations have learned to leverage great-power competition—using the threat of Chinese engagement to extract concessions from Western partners while not actually signing with Beijing.

This is precisely Toroama’s strategy. Bougainville’s vulnerability to Chinese economic coercion functions as a trigger for Australian support mechanisms. The rejection of CMOC signals alignment with Canberra’s preferences without requiring formal commitments. Australia cannot afford to let Bougainville’s independence project fail and potentially fall into Beijing’s orbit. The threat of what might happen if Bougainville accepted Chinese investment creates leverage that the actual acceptance would eliminate.

PNG’s Prime Minister James Marape faces a more complex calculation. His resource nationalism—the insistence that PNG must control its natural resources—aligns with Bougainville’s rejection of foreign mining dominance. But Marape also needs Chinese investment for PNG’s broader development agenda. The PNG-China Bilateral Investment Treaty provides a framework for Chinese investment that Bougainville’s autonomous status complicates but does not eliminate.

The result is a three-way negotiation where each party’s interests partially align and partially conflict. PNG wants Bougainville to remain part of the federation but needs the revenues that Panguna could generate. Bougainville wants independence but needs PNG’s recognition. Both want development but differ on acceptable partners. China wants resource access but cannot easily navigate the distributed consent requirements that Bougainville’s governance imposes.

What Beijing’s Toolkit Cannot Buy

China’s economic engagement across the Pacific has followed a recognizable pattern: infrastructure loans, port development, telecommunications investment, fisheries agreements. Ten of fourteen Pacific Island Countries have received Belt and Road Initiative financing. China’s share of Pacific trade rose from 13% in 2012 to 29% in 2023. The model works through state-level relationships—deals negotiated with national governments that can be enforced through sovereign obligations.

Bougainville breaks this model. The ABG holds 72.9% of Bougainville Copper Limited, but that ownership does not translate into operational control over mining. The Mining Act places ultimate authority with customary landowners whose consent cannot be secured through government-to-government agreements. CMOC’s proposal involved equity participation that would have diluted the ABG’s stake—a structure Toroama explicitly rejected as unauthorized.

The deeper problem for Beijing is that economic coercion requires economic dependence. Bougainville’s extreme poverty paradoxically increases its bargaining power by making credible the threat to leave Panguna closed indefinitely. A wealthier polity with developed expectations would face pressure to accept investment terms. Bougainville can afford to wait because its population has adapted to subsistence livelihoods that do not require mining revenues.

Diaspora remittances provide an alternative income stream that reduces mining’s economic necessity. Cocoa production has improved livelihoods for smallholder farmers. These are not substitutes for Panguna’s potential billions, but they are sufficient to sustain a population that remembers what the mine cost last time.

Limits and Non-Limits

Does Bougainville’s rejection signal limits to Beijing’s Pacific economic coercion? The answer is both yes and no.

Yes, in the sense that China’s state-centric economic instruments encounter structural barriers when they meet governance systems designed to prevent exactly the kind of top-down resource extraction that Chinese SOEs prefer. The Bougainville Mining Act creates a legal architecture where Beijing’s comparative advantages—speed, scale, tolerance for risk, state backing—become disadvantages. CMOC cannot out-negotiate hundreds of clan groups with veto power.

No, in the sense that Bougainville represents a specific case with specific features that do not generalize across the Pacific. The civil war created a political settlement that embedded landowner authority. The matrilineal land tenure system distributes decision-making in ways that defeat centralized leverage. The traumatic memory of Panguna shapes elite and popular attitudes in ways that cannot be overcome by better terms.

Other Pacific nations lack these features. Solomon Islands accepted Chinese security engagement. Kiribati switched diplomatic recognition from Taipei to Beijing. Fiji has welcomed Chinese infrastructure investment. The pattern suggests that Beijing’s economic instruments work where governance structures permit state-level deals—and fail where they don’t.

The more interesting question is whether other Pacific nations might adopt Bougainville-style governance reforms specifically to resist Chinese economic pressure. The Mining Act offers a template: distribute consent requirements widely enough that no single point of leverage can secure approval. This would require fundamental changes to land tenure and resource governance that few Pacific governments would willingly undertake. But the option exists.

The Independence Gamble

Toroama’s rejection of CMOC delays the revenue generation that could fund Bougainville’s independence. This is the trade-off he has accepted: slower progress toward statehood in exchange for avoiding the dependencies that Chinese investment would create.

The gamble is that alternative partners will emerge. Australian mining companies have shown interest in Panguna but face their own constraints—shareholder pressure over environmental and social governance, reputational risks from the mine’s history, uncertainty about Bougainville’s political trajectory. Western development finance institutions could provide infrastructure support but lack the risk appetite for large-scale mining investment.

The most likely scenario is continued limbo. Bougainville maintains its independence aspiration without achieving it. Panguna remains closed. The ABG continues negotiating with potential partners while using the threat of Chinese engagement to extract Western support. This is sustainable indefinitely—Bougainville has survived thirty-five years without Panguna revenues.

What changes the trajectory? PNG could recognize independence without fiscal preconditions, but Port Moresby has no incentive to do so. A Western consortium could offer terms that satisfy both the ABG and landowners, but the commercial case remains uncertain. China could develop new instruments that work through clan structures rather than around them, but this would require abandoning the state-centric model that defines Beijing’s economic diplomacy.

The most probable future is that Bougainville becomes a permanent example of what Beijing’s economic coercion cannot achieve—not because Chinese money isn’t attractive, but because the governance architecture that emerged from civil war created antibodies against exactly the kind of engagement China offers.

FAQ: Key Questions Answered

Q: Why did Bougainville vote for independence but remain part of Papua New Guinea? A: The 2019 referendum was non-binding. PNG’s parliament must ratify the result, and Port Moresby has conditioned recognition on Bougainville demonstrating fiscal self-sufficiency. The two governments continue negotiating, with Bougainville targeting 2027 for independence.

Q: How much is the Panguna mine worth? A: The deposit contains an estimated 5.3 million tonnes of copper and 547 tonnes of gold. At current prices, this represents tens of billions of dollars in potential value, though extraction costs and the extensive rehabilitation required make net revenues uncertain.

Q: Could China still invest in Bougainville through other channels? A: Theoretically yes, but the Bougainville Mining Act requires customary landowner consent for any mining activity. Chinese companies would face the same distributed consent requirements that defeated the CMOC proposal. Non-mining investment faces fewer barriers but offers less strategic value.

Q: What happens if Bougainville never achieves independence? A: Bougainville would remain an autonomous region of PNG with substantial self-governance but without sovereign status. This arrangement has functioned since 2005 and could continue indefinitely, though it would represent a defeat for the independence movement that won 97.7% support in the referendum.

The Pit That Remembers

Panguna’s scar will outlast everyone currently negotiating its future. The pit will still be there when Toroama leaves office, when CMOC pursues opportunities elsewhere, when the great-power competition that frames Pacific geopolitics has shifted to new configurations. The mine’s closure created the governance structures that now prevent its reopening on terms that any foreign investor would accept.

This is Bougainville’s peculiar contribution to the study of economic coercion: proof that trauma can be institutionalized, that memory can be encoded in law, that the worst outcomes of extractive capitalism can generate antibodies against its return. Beijing’s Pacific strategy encounters many obstacles—Australian counter-investment, American security guarantees, island nationalism. In Bougainville, it encountered something rarer: a society that designed its institutions specifically to prevent what China offers.

The limits to Beijing’s economic coercion are not universal. They are specific, historical, and hard-won. Bougainville paid for them with a decade of war and a generation of development foregone. Other Pacific nations may not choose to pay that price. But the template exists for those who want it.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- Bougainville Vision 2052 - The ABG’s long-term development strategy outlining independence preparation

- Berghof Foundation Bougainville Report - Analysis of post-conflict governance and reconciliation architecture

- Lowy Institute Pacific Analysis - Assessment of information dynamics and influence in Pacific Island states

- Asia Society Policy Institute - Media analysis of Chinese influence across Pacific nations

- PNG National Research Institute - Research on Bougainville government revenue options

- UNCTAD Investment Policy Hub - Documentation of China-PNG bilateral investment treaty

- Earthworks Troubled Waters Report - Environmental assessment of mining impacts in the Pacific