Why America's Pacific allies are losing sleep over the Pentagon's new priorities

The 2026 National Defense Strategy demotes China from top threat to regional concern. For Japan, the Philippines, and Australia—facing Beijing's gray-zone coercion daily—the timing could not be worse. What happens when the guarantor's attention wanders?

🎧 Listen to this article

The Reassurance Gap

For seventy years, America’s Indo-Pacific allies operated under a simple assumption: Washington would prioritize their security because their security was Washington’s security. That assumption died in January 2026.

The Pentagon’s new National Defense Strategy inverts decades of strategic logic. Homeland defense now ranks first. China drops to second—a regional concern to be managed through “strength, not confrontation.” The shift reflects domestic political realities: border security polls better than Taiwan contingencies. But for Tokyo, Manila, and Canberra, the message lands differently. America’s most exposed allies now face China’s most aggressive behavior with diminished confidence that Washington will show up.

This is not abandonment. American forces remain forward-deployed. Treaties remain in force. But strategy is about signals, and signals shape behavior. When the Pentagon explicitly deprioritizes the threat your military exists to counter, you notice. So does Beijing.

The Threat Timeline Mismatch

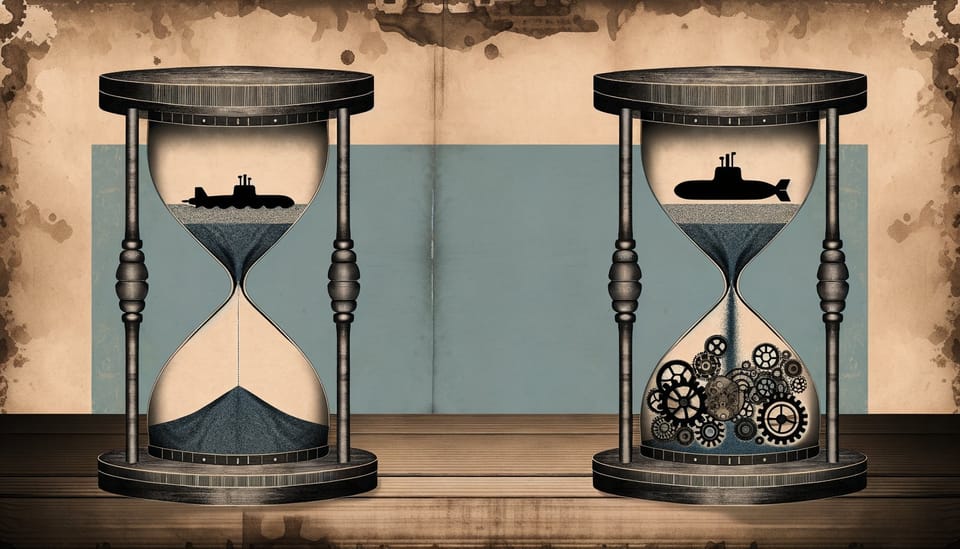

The core problem is temporal. America and its allies experience China’s challenge on fundamentally different clocks.

For Washington, China represents a long-term strategic competitor—dangerous, yes, but manageable through industrial rebuilding, diplomatic engagement, and patient deterrence. The 2026 NDS speaks of “preventing China from dominating” the United States or its allies, language calibrated for decades of competition rather than years of crisis. This framing suits a superpower 7,000 miles from the South China Sea.

For the Philippines, the threat arrived yesterday. On June 17, 2024, Chinese Coast Guard vessels blocked, rammed, and boarded a Philippine resupply mission to Second Thomas Shoal. Sailors were injured. A vessel was damaged. This was not an abstraction requiring strategic patience. It was an attack on sovereign personnel conducting a lawful resupply operation within Philippine waters.

Japan’s 2022 National Security Strategy describes China as presenting “unprecedented and the greatest strategic challenge” to Japanese security. Not a challenge to be managed over generations. The greatest. Now.

Australia occupies a middle position—geographically distant enough to feel less immediate pressure, close enough to understand what’s coming. Canberra’s 2024 defense review committed to AUKUS nuclear submarines precisely because Australian planners recognize that today’s relative calm in the Taiwan Strait could become tomorrow’s regional conflagration.

These are not disagreements about facts. They are disagreements about urgency. And urgency determines resource allocation, force posture, and political will.

The research reveals a stark assessment: “No Indo-Pacific allies are considered to be carrying their fair share of the burden for deterrence against China.” This judgment, embedded in American strategic thinking, misses the point. Allies calibrate burden-sharing to perceived American commitment. When that commitment appears to waver, allies face an impossible choice: spend more on defense that may prove insufficient without American support, or hedge toward accommodation with Beijing.

Neither option strengthens deterrence.

What Deprioritization Actually Means

The 2026 NDS does not withdraw American forces from the Pacific. It does not abrogate the Mutual Defense Treaty with the Philippines or the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty. What it does is subtler and potentially more corrosive: it changes the hierarchy of American strategic attention.

In bureaucratic Washington, hierarchy determines everything. Which threats get the best analysts. Which commands receive the newest equipment. Which contingencies dominate wargaming. Which officers build careers preparing for which conflicts. The Pentagon’s explicit statement that homeland defense now outranks China deterrence reshapes all of these institutional flows.

Consider the implications for munitions. The December 2025 report to Congress on Chinese military power warned that “China maintains a large and growing arsenal of nuclear, maritime, conventional long-range strike, cyber, and space capabilities able to directly threaten Americans’ security.” This assessment supports the homeland-first logic. But the same industrial base that would defend the American homeland must also supply forward-deployed forces in a Taiwan contingency. If production priorities shift toward homeland defense systems, stockpiles for Pacific operations suffer.

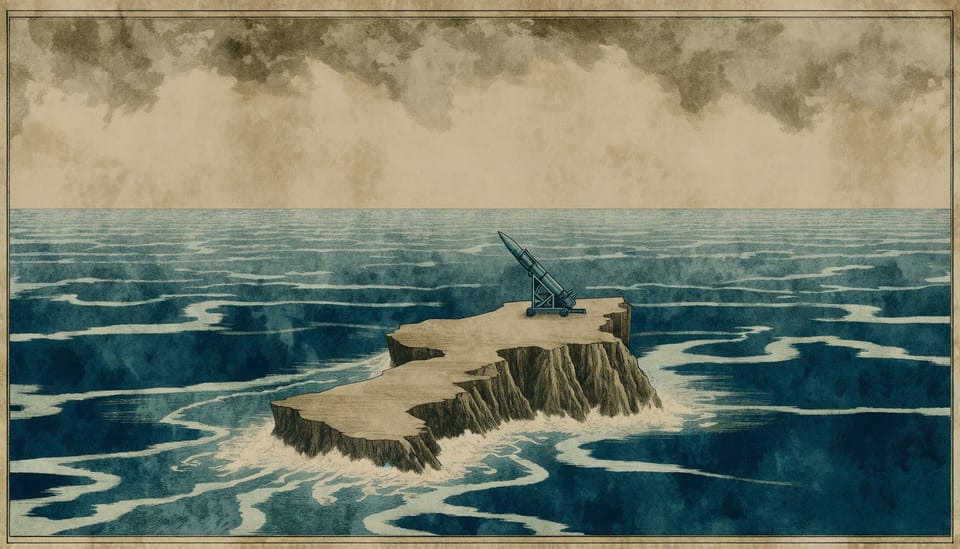

The numbers are already unfavorable. A high-intensity conflict in the Western Pacific would exhaust American precision munitions within weeks. Allied stockpiles are thinner still. Japan has increased defense spending dramatically since 2022, but industrial capacity takes years to build. Australia’s AUKUS submarines won’t arrive until the 2030s. The Philippines lacks the economic base for major military modernization regardless of political will.

Deprioritization doesn’t remove American capability from the Pacific. It removes American urgency. And urgency is what drives the industrial mobilization, logistics prepositioning, and operational planning that convert capability into deterrence.

The Gray-Zone Acceleration

Beijing reads American strategy documents carefully. The shift from “pacing threat” to regional concern will not go unnoticed.

China’s gray-zone operations against the Philippines have intensified steadily since 2023. Water cannon attacks, vessel ramming, aerial harassment—these actions fall below the threshold of armed attack that would clearly trigger American treaty obligations. They are designed to change facts on the ground (or water) without provoking the response that overt military action would demand.

The 2024 Joint Sword exercises around Taiwan represented China’s largest naval deployment since the 1996 Taiwan Strait Crisis, simulating blockade operations. These exercises serve multiple purposes: testing operational concepts, pressuring Taipei, and signaling to Washington that the costs of intervention are rising.

American deprioritization creates space for more aggressive gray-zone operations. If Washington signals that China is not its primary concern, Beijing may calculate that incremental pressure carries lower risk of American response. Each successful coercion—each resupply mission blocked, each fishing vessel harassed, each air defense identification zone violated without consequence—shifts the baseline of acceptable behavior.

This is the ratchet dynamic. What was provocative in 2023 becomes routine by 2026. What was routine becomes the starting point for further escalation. And allies who cannot respond effectively alone face a choice between accepting gradual erosion of their sovereignty or risking escalation they cannot control.

The Philippines has sought to publicize Chinese aggression, releasing footage of Coast Guard attacks and appealing to international opinion. This strategy works only if it generates American response. If Washington’s attention lies elsewhere, Manila’s exposure becomes Beijing’s opportunity.

Alliance Architecture Under Strain

The Indo-Pacific security architecture rests on bilateral treaties radiating from Washington like spokes from a hub. The United States maintains separate defense commitments to Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, Australia, and Thailand. These arrangements served American interests when the primary goal was preventing any single power from dominating Asia. They also served allied interests when American commitment was unquestioned.

Deprioritization strains this architecture in multiple ways.

First, it encourages hedging. Allies who doubt American reliability have incentives to develop independent capabilities, including capabilities Washington would prefer they not possess. Japan’s constitutional reinterpretation to permit collective self-defense was already a significant step. South Korea periodically debates nuclear weapons development. Australia’s pursuit of nuclear-powered submarines through AUKUS reflects recognition that conventional forces may prove insufficient against a peer adversary.

These developments are not inherently destabilizing. Allied capability improvements can strengthen deterrence. But they also introduce coordination problems. If Japan develops long-range strike capabilities to compensate for uncertain American support, Tokyo gains independent escalation options that Washington cannot control. The alliance becomes less predictable—and predictability is what deters.

Second, deprioritization complicates minilateral arrangements. The Quad (United States, Japan, Australia, India) and AUKUS emerged partly to supplement bilateral alliances with networked cooperation. These arrangements depend on American leadership and commitment. If Washington signals reduced priority for the Indo-Pacific, the glue holding these coalitions together weakens.

According to analysis from the Lowy Institute, minilaterals have proven more enduring than critics predicted, partly because they address specific functional needs rather than attempting comprehensive security guarantees. But functional cooperation still requires strategic alignment. If American and allied threat timelines diverge too dramatically, even issue-specific cooperation becomes harder to sustain.

Third, the bilateral hub-and-spoke model creates coordination gaps that China can exploit. Japan and the Philippines share concerns about Chinese coercion but lack formal alliance ties with each other. Australia and Japan have deepened defense cooperation but operate under different treaty frameworks with Washington. When American attention shifts elsewhere, these coordination gaps widen.

The Burden-Sharing Paradox

The 2026 NDS explicitly calls for “increasing burden-sharing with U.S. allies and partners.” This reflects longstanding American frustration that allies free-ride on American security guarantees while spending insufficiently on their own defense.

The frustration is not baseless. Japan’s defense spending remained below 1% of GDP for decades. Australia’s defense budget, while growing, still falls short of the investment required to project meaningful power beyond its immediate region. The Philippines lacks resources for major modernization regardless of political intent.

But the burden-sharing demand contains a paradox. Allies calibrate their defense spending to perceived threat levels and American commitment. If Washington signals reduced commitment, rational allies might increase spending to compensate—or they might conclude that no feasible spending level can substitute for American power and instead pursue accommodation with Beijing.

The historical record suggests the second response is more common. When great powers signal retrenchment, smaller allies typically hedge rather than arm. They lack the industrial base, technological capacity, and strategic depth to substitute for great-power protection. Increased spending on inadequate capabilities provides neither deterrence nor reassurance.

Japan represents a partial exception. Tokyo has committed to doubling defense spending to 2% of GDP by 2027, acquiring counterstrike capabilities, and reforming its defense industrial base. Research from the International Institute for Strategic Studies highlights deepening U.S.-Japan defense-industrial cooperation, including potential co-production arrangements that could accelerate Japanese capability development.

But even Japan’s ambitious modernization depends on American technology, intelligence, and—crucially—the credibility of American extended deterrence. Japan’s counterstrike capabilities matter only if Tokyo believes Washington will support their use. If that belief erodes, the capabilities become expensive symbols rather than effective deterrents.

What Beijing Calculates

Chinese strategic planners face their own timeline pressures. The 2027 centennial goal for PLA modernization—tied to the Chinese Communist Party’s founding anniversary—creates institutional momentum toward demonstrating military capability. Taiwan remains the most likely context for such demonstration.

Xi Jinping has consolidated power to a degree unprecedented since Mao. His core beliefs, shaped by the Cultural Revolution’s chaos and the Soviet Union’s collapse, emphasize that only centralized control prevents catastrophic failure and that the West will never accept China’s rise. These beliefs drive risk-acceptance on geopolitical confrontation even as they counsel risk-aversion on domestic political reform.

American deprioritization enters this calculation in complex ways.

On one hand, reduced American focus on China might lower the perceived costs of aggressive action. If Washington signals that homeland defense matters more than Taiwan contingencies, Beijing might calculate that American intervention in a Taiwan scenario has become less likely. This calculation could encourage more aggressive coercion or, in extreme scenarios, military action.

On the other hand, the 2026 NDS explicitly commits to “deterring China through military strength.” American forces remain formidable. The industrial base, while strained, continues producing advanced capabilities. And American political dynamics can shift rapidly—a crisis in the Taiwan Strait could instantly reprioritize China regardless of what any strategy document says.

Beijing’s most likely response is intensified gray-zone pressure combined with continued military modernization. Test American and allied responses at the margins. Probe for weaknesses in coordination. Establish new baselines of acceptable behavior. Avoid the kind of overt aggression that would force American re-engagement while steadily improving the correlation of forces for a future contingency.

This is the patient strategy of an actor confident in long-term trends. China’s economy, despite recent difficulties, dwarfs any individual Indo-Pacific ally. Its defense industrial base produces ships, missiles, and aircraft at rates the United States cannot match. Time, in Beijing’s calculation, favors China—provided it avoids the kind of premature confrontation that would unite American and allied opposition.

American deprioritization reinforces this patience. Why risk everything on Taiwan in 2027 when the correlation of forces improves every year and American attention drifts elsewhere?

The Credibility Compound

Deterrence is ultimately about belief. Does Beijing believe Washington would fight for Taiwan? Does Tokyo believe Washington would honor its treaty obligations if Japan faced Chinese attack? Does Manila believe American forces would respond to a Chinese seizure of Philippine-occupied features in the South China Sea?

These beliefs compound over time. Each instance of American restraint in the face of allied pressure creates precedent. Each strategic document that deprioritizes the region erodes confidence. Each burden-sharing demand that goes unmet generates friction.

The research identifies a troubling dynamic: American deprioritization creates “hostage-like situations for allied territories hosting U.S. forces, making them targets without corresponding influence over U.S. strategy.” Okinawa hosts massive American military installations that would be primary targets in any Taiwan contingency. Yet Okinawan residents have limited voice in American strategic decisions, and the 2026 NDS explicitly prioritizes American homeland defense over forward operations.

This dynamic applies across the region. Australian facilities support American intelligence and communications networks critical for Pacific operations. Philippine bases provide access points for potential Taiwan contingencies. Japanese installations host American forces whose primary mission is regional deterrence. All of these allies bear risks from American forward presence while watching Washington signal reduced commitment to the missions that presence supports.

The credibility compound works in reverse as well. If allies doubt American commitment, they become less willing to support American operations. Base access becomes more politically contested. Host-nation support becomes harder to sustain. The forward posture that enables American power projection erodes from within.

Intervention Points

Three leverage points could alter the current trajectory.

Industrial acceleration. The most concrete response to allied anxiety is demonstrable American commitment to the defense industrial base. Not speeches about rebuilding capacity—actual production increases in the munitions, ships, and aircraft that would matter in a Pacific conflict. Japan’s defense industrial reforms create opportunities for co-production arrangements that could accelerate both American and allied capability development while demonstrating sustained commitment. The challenge is timeline: industrial capacity takes years to build, and allies face immediate threats.

Gray-zone response frameworks. The gap between gray-zone coercion and armed attack creates ambiguity that China exploits. Clearer frameworks for allied response to gray-zone operations—including American support for non-kinetic countermeasures—could raise the costs of Chinese coercion without requiring the kind of military escalation that current strategy seeks to avoid. The Philippines’ strategy of publicizing Chinese aggression needs American amplification to generate consequences. The trade-off is escalation risk: any framework that raises costs for China also raises risks of miscalculation.

Minilateral deepening. If American attention shifts elsewhere, allied coordination becomes more critical. Japan-Philippines-Australia trilateral cooperation could provide mutual support that partially compensates for uncertain American commitment. The Quad could evolve from diplomatic forum to operational coordination mechanism. AUKUS technology sharing could accelerate beyond submarines to include other capabilities relevant to regional deterrence. The trade-off is complexity: more coordination arrangements mean more potential friction points, and none of these groupings can substitute for American power.

None of these interventions resolves the fundamental tension. American domestic politics drive the deprioritization. Indo-Pacific geography drives allied threat perceptions. These structural forces will not align through clever policy design.

The Default Trajectory

Absent significant course correction, the most likely trajectory involves gradual erosion rather than dramatic rupture.

American forces remain in the Pacific. Treaties remain in force. But the gap between formal commitments and perceived reliability widens. Allies hedge more aggressively—some toward independent capabilities, others toward accommodation with Beijing. Gray-zone operations intensify as China tests the boundaries of acceptable coercion. Coordination among allies becomes more difficult as threat perceptions diverge.

Taiwan remains the critical variable. A Chinese move against Taiwan would instantly reprioritize American strategy regardless of any NDS. But the window before such a move—the period when deterrence must hold—is precisely when American deprioritization matters most. If Beijing concludes that American commitment has weakened sufficiently, the calculation that has restrained Chinese action for decades could change.

The 2026 NDS may prove a temporary document, superseded by events or subsequent administrations. American strategy has shifted before and will shift again. But allies cannot plan on the assumption that Washington will return to previous priorities. They must prepare for a world in which American attention lies elsewhere—and in that world, the risks they face grow larger while the reassurance they receive grows thinner.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Does the 2026 National Defense Strategy mean the US is abandoning its Pacific allies? A: No. American forces remain forward-deployed, and treaty commitments remain in force. However, the explicit deprioritization of China signals reduced urgency that could affect resource allocation, operational planning, and allied confidence in American support during crises.

Q: Why is China conducting more aggressive operations in the South China Sea? A: China’s gray-zone operations—ramming vessels, blocking resupply missions, harassing aircraft—are designed to change facts on the water without triggering the kind of armed response that would invoke American treaty obligations. These operations test allied resolve and establish new baselines of acceptable behavior.

Q: What is the “burden-sharing” debate really about? A: American officials argue that allies spend too little on defense and rely excessively on American protection. Allies counter that their spending levels reflect American commitment signals—if Washington appears less committed, allies may hedge toward accommodation rather than increased defense investment.

Q: Could Japan or Australia develop nuclear weapons if American commitment continues to decline? A: Both nations possess the technical capability but face significant political and legal constraints. Japan’s pacifist constitution and Australia’s non-proliferation commitments would require fundamental policy reversals. More likely near-term responses include conventional capability improvements and deeper regional security cooperation.

The Quiet Reckoning

The Indo-Pacific’s future will not be decided by strategy documents. It will be decided by the accumulation of small choices—a resupply mission contested or completed, a gray-zone incursion challenged or accepted, an allied request supported or deflected.

American strategists speak of “integrated deterrence” and “burden-sharing” as though these concepts translate cleanly across the Pacific. They do not. For a Philippine sailor watching Chinese Coast Guard vessels approach, deterrence is not a theory. It is whether help arrives.

The 2026 NDS reflects genuine American concerns: a homeland facing new vulnerabilities, an industrial base requiring reconstruction, a political system demanding visible returns on security investments. These concerns are legitimate. But strategy involves choices, and choices have consequences.

Washington has chosen to signal that China is not its primary concern. Beijing has heard that signal. So have Tokyo, Manila, and Canberra. What they do with that information will shape the Pacific for decades.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- 2026 National Defense Strategy - Primary source for Pentagon’s strategic reprioritization

- Annual Report to Congress on China Military Power 2025 - Assessment of PLA capabilities and homeland threats

- Japan’s National Security Strategy 2022 - Japan’s characterization of China as greatest strategic challenge

- Lowy Institute analysis on Indo-Pacific minilaterals - Assessment of regional security architecture evolution

- IISS analysis on US-Japan defense-industrial cooperation - Examination of allied capability development pathways

- ICWA analysis on US strategic minilaterals - Framework for understanding Quad and AUKUS dynamics

- Frontiers analysis on maritime law enforcement - Legal frameworks governing gray-zone responses