When the Taps Run Dry: The Cascading Consequences of Water Infrastructure Failure in Australia

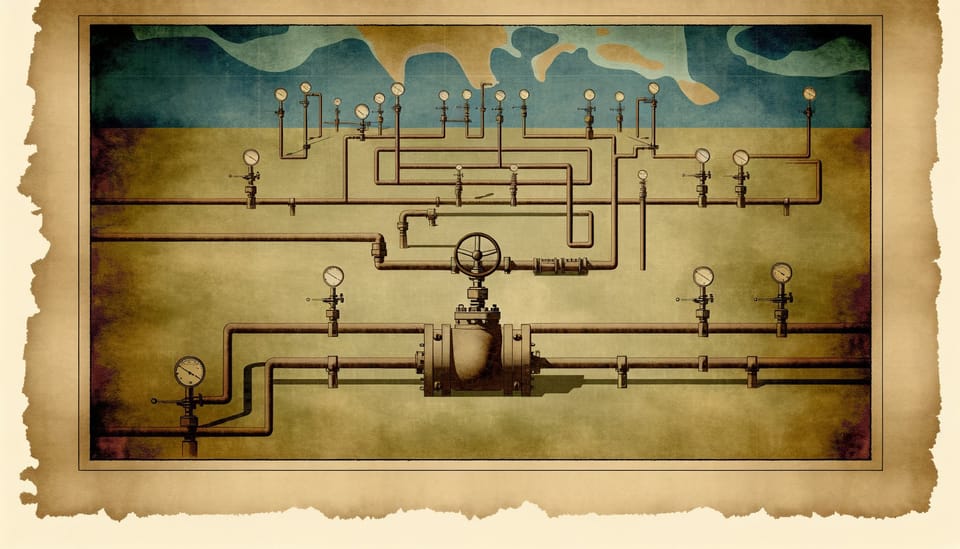

Australia's water and sewerage systems serve millions through infrastructure so reliable it has become invisible. That invisibility masks profound vulnerability—to cyber attack, climate stress, and institutional neglect. When disruption comes, its consequences will cascade far beyond burst pipes.

When the Taps Run Dry

Sydney’s water network serves 5.4 million people through a system so reliable it has become invisible. Pipes, pumps, and treatment plants operate in the background of daily life, their presence noticed only in absence. That invisibility is precisely the problem.

Australia’s water and sewerage infrastructure represents a peculiar category of critical asset: one whose success breeds complacency. Unlike electricity, which announces its failure with darkened screens and silenced devices, water infrastructure collapses gradually. A contamination event may take days to detect. A sewage system failure spreads through aquifers over weeks. By the time disruption becomes visible, its consequences have already metastasised.

The Critical Infrastructure Annual Risk Review 2024 places water and sewerage among the most frequently targeted sectors for cyber incidents—30% of all critical infrastructure attacks. Yet the sector receives a fraction of the security investment afforded to electricity or telecommunications. This asymmetry reflects a deeper failure of institutional imagination: the inability to think through consequences that unfold on timescales longer than a news cycle.

First Order: The Immediate Cascade

Major disruption to water and sewerage systems triggers consequences that propagate with mechanical precision. The sequence is predictable because it follows the physics of interdependence.

Hospitals face the most immediate crisis. Modern healthcare facilities consume extraordinary volumes of water—for sterilisation, dialysis, cooling systems, and basic sanitation. When supply fails or becomes contaminated, elective surgeries halt within hours. The historical parallel is instructive: before antiseptic technique, surgical mortality approached 80%. A hospital without reliable water reverts to something resembling that condition, not through ignorance but through infrastructure failure.

Emergency departments become triage centres for a different kind of casualty. Dialysis patients require treatment every 48-72 hours; without it, they die. Contaminated water supply creates its own patient surge—gastrointestinal illness, dehydration, infections. The healthcare system simultaneously loses capacity and gains demand.

The aged care sector faces particular vulnerability. Residents cannot easily relocate. Staff ratios that barely function under normal conditions collapse under crisis. The sector’s regulatory framework assumes continuous utility service; no contingency exists for its absence.

Schools close. This is not merely an educational disruption but an economic one—parents cannot work when children require supervision. The productivity loss compounds across sectors, affecting businesses that have no direct connection to water infrastructure.

Data centres, those temples of the digital economy, require cooling water in quantities that would surprise most observers. Their diesel backup generators can run indefinitely with refuelling—or so the marketing claims. Reality is less accommodating. Cooling systems fail without water. Servers overheat. The cloud, that metaphor of ethereal permanence, proves remarkably dependent on physical pipes.

The economic modelling is stark. The Australian Water Association estimates potential GDP losses of $452 billion from water-related extreme weather events between 2022 and 2050. That figure captures only the direct impacts. It does not account for the cascading failures that transform a water crisis into a systemic one.

Second Order: The Institutional Unravelling

First-order consequences follow engineering logic. Second-order consequences follow social logic—and social systems are far less predictable.

Public trust erodes with remarkable speed. A single contamination event can destroy decades of institutional credibility. The psychology is asymmetric: a thousand days of clean water create less trust than one day of contaminated water destroys. This is not irrational. It reflects an accurate assessment that infrastructure failure reveals something about institutional competence that normal operations conceal.

Political consequences follow trust erosion. Governments that fail to maintain basic services face electoral punishment disproportionate to the failure’s scope. Water is different from other infrastructure in this regard. Electricity failures are annoying. Transport failures are frustrating. Water failures are visceral—they touch the body directly, create disgust, trigger primal responses about safety and contamination.

The regulatory architecture begins to strain. Australia’s water governance operates through a complex federation of state, territorial, and local authorities. The Security of Critical Infrastructure Act 2018 imposes notification requirements and security obligations, but enforcement assumes normal operating conditions. During crisis, the information asymmetry between federal bureaucrats and local operators becomes acute. Each level of government can claim insufficient knowledge to justify non-intervention—a structural accountability gap that transforms during emergencies into a coordination failure.

Insurance markets respond with their own logic. Business interruption policies typically impose 24-72 hour waiting periods before coverage activates. For many small businesses, that gap is fatal. The waiting period functions as a speciation bottleneck—only firms with sufficient reserves survive the initial shock. This concentrates market power in larger enterprises, accelerating trends toward consolidation that were already underway.

Property markets register the shock with lag but permanence. Areas perceived as vulnerable to water infrastructure failure see values decline. The decline becomes self-reinforcing: lower values mean lower rate bases, which mean reduced infrastructure investment, which increases vulnerability. Some communities enter a spiral from which recovery becomes progressively more difficult.

Indigenous communities face particular second-order impacts. Traditional water knowledge and management practices that sustained populations for millennia have been systematically marginalised by colonial and post-colonial water governance. Infrastructure failure exposes this marginalisation while simultaneously creating opportunities for Indigenous-led water management—but only if governance structures permit such innovation.

Third Order: The Structural Transformation

Third-order consequences reshape the systems themselves. They operate on timescales of years and decades, long after the immediate crisis has faded from headlines.

The most profound transformation concerns the relationship between citizens and infrastructure. Reliable public utilities create a particular kind of citizenship—one that takes basic services for granted and focuses political attention on higher-order concerns. Infrastructure failure reverses this. Citizens who have experienced water crisis become permanently altered in their relationship to the state. They stockpile. They distrust. They vote differently.

This transformation has international dimensions. Foreign investors scrutinise infrastructure resilience with increasing sophistication. The Foreign Investment Review Board’s nil monetary threshold for national security businesses reflects awareness that water infrastructure represents strategic vulnerability. But the screening framework assumes discrete transactions. It cannot address the gradual accumulation of foreign ownership in water entitlements through agricultural investment, or the complex supply chain dependencies that embed foreign components in critical systems.

Climate change compounds every vulnerability. The Productivity Commission’s National Water Reform 2024 Inquiry notes that “climate change is reducing rainfall reliability and increasing extreme weather events.” This is not merely a future risk but a present reality reshaping infrastructure requirements. Systems designed for historical climate patterns face conditions for which they were never engineered.

The temporal mismatch is structural. Water infrastructure operates on generational timescales—pipes laid today will serve for fifty years or more. Climate projections span similar periods but with increasing uncertainty. Political cycles reset every three to four years. Investment decisions made under one government bind successors to conditions they did not choose. This temporal incommensurability creates systematic underinvestment in resilience.

The environmental dimension extends beyond climate. Sewage systems function as evolutionary accelerators for antibiotic resistance. The concentration of unmetabolised antibiotics in wastewater—estimates suggest 30-90% of administered doses pass through unchanged—creates high-density microbial populations under intense selective pressure. Combined sewage overflows during heavy rainfall events create pulsed, high-concentration pharmaceutical releases. The public health consequences unfold over decades, invisible until resistance patterns emerge in clinical settings.

The Geography of Vulnerability

Not all Australians face equal exposure. The geography of water infrastructure vulnerability maps onto existing patterns of disadvantage with uncomfortable precision.

Remote communities, particularly Indigenous communities, experience infrastructure failure as an intensification of chronic underservice rather than an acute departure from normalcy. The gap between urban and remote water quality is already substantial; crisis widens it further. Emergency response frameworks assume communication infrastructure that remote areas often lack, creating what one analysis describes as “distributed pattern recognition failure”—the inability of healthcare and emergency networks to identify emerging threats when data transmission fails.

Urban vulnerability concentrates in older suburbs where infrastructure has aged beyond design life. Asset replacement cycles have lagged population growth and climate intensification. The political economy of infrastructure investment favours visible new construction over invisible maintenance. Pipes that function adequately receive no attention until they fail catastrophically.

Coastal areas face compound risks. Sea level rise increases saltwater intrusion into aquifers. Storm surge threatens treatment facilities. The infrastructure most exposed to climate impacts is often the oldest, having been sited according to historical rather than projected conditions.

This geography creates a troubling dynamic. Those with resources relocate away from vulnerability. Those without resources remain. The population exposed to infrastructure risk becomes progressively less politically powerful, reducing pressure for remediation. Australia risks creating sacrifice zones—areas where infrastructure failure becomes normalised rather than addressed.

The Intervention Calculus

What might alter this trajectory? The options are constrained by institutional inertia, fiscal limits, and the fundamental challenge of investing against risks that may not materialise within electoral cycles.

The first intervention point is governance architecture. Australia’s federated water management creates coordination costs that exceed any efficiency gains from local control. A national water security framework—not merely coordination mechanisms but genuine authority over critical infrastructure—would enable the kind of systemic investment that current arrangements preclude. The trade-off is sovereignty: states would cede control over assets they currently manage. Political feasibility: LOW. The federation was designed to prevent such centralisation, and no crisis short of catastrophe would generate sufficient political will to overcome that design.

The second intervention point is investment frameworks. Current accounting treats infrastructure maintenance as cost rather than value preservation. This creates systematic incentives to defer maintenance, accumulating technical debt that compounds until failure. Shifting to asset-value accounting—treating infrastructure degradation as equivalent to financial loss—would align institutional incentives with long-term resilience. The trade-off is short-term fiscal constraint: governments would face immediate pressure to fund maintenance currently deferred. Political feasibility: MEDIUM. The accounting change is technical enough to avoid public opposition but requires sustained bureaucratic commitment.

The third intervention point is insurance market design. Current business interruption frameworks create the waiting-period bottleneck that concentrates market power during crises. Mandatory parametric insurance—coverage that triggers automatically when defined conditions occur, without waiting periods—would distribute risk more broadly. The trade-off is premium cost: businesses currently self-insuring against the waiting period would face explicit insurance costs. Political feasibility: MEDIUM. The insurance industry would resist, but post-crisis political pressure could overcome that resistance.

What actually will happen? Most likely, incremental improvements following each crisis, insufficient to address structural vulnerabilities, followed by gradual forgetting as attention moves elsewhere. The research on public attention to environmental issues is unambiguous: concern peaks immediately after events and decays with predictable half-lives. Infrastructure investment requires sustained attention that democratic systems struggle to maintain.

The Deeper Pattern

Australia’s water infrastructure vulnerability reveals something about modern societies that extends beyond any single sector. The systems that sustain contemporary life have become so reliable that their reliability is mistaken for permanence. This is a category error with consequences.

Every complex system accumulates entropy. Pipes corrode. Treatment plants age. Knowledge of how systems actually function—as opposed to how documentation claims they function—resides in workers who retire or leave. The forensic engineering literature describes how each corrosion layer in failed infrastructure maps to specific organisational decisions: a maintenance deferral here, a budget cut there, a retirement not replaced. The physical failure is the final expression of decades of institutional choices.

The water sector’s particular vulnerability lies in its invisibility. Electricity announces itself through light and motion. Telecommunications connect visibly. Water flows underground, noticed only in its absence. This invisibility extends to investment: voters reward visible projects, not invisible maintenance. Politicians cut ribbons on new treatment plants; nobody celebrates a pipe that didn’t fail.

Climate change removes the margin for error that invisibility once afforded. Historical infrastructure could be undersized, undermaintained, underinvested—and still function adequately because conditions remained within design parameters. Those parameters no longer hold. The gap between infrastructure capacity and demand grows with each extreme weather event, each population increase, each deferred maintenance cycle.

Australia faces a choice it has not yet acknowledged. One path leads to systematic investment in resilience—expensive, politically unrewarding, requiring sustained attention across multiple electoral cycles. The other path continues current patterns until crisis forces reactive response. The second path costs more in the long run but distributes those costs across future governments and future citizens. The political economy of infrastructure investment makes the second path more likely.

The question is not whether major disruption will occur. The question is whether disruption will trigger transformation or merely recovery to previous vulnerability. History suggests recovery. The systems that govern infrastructure investment will reproduce the conditions that created vulnerability unless those systems themselves change.

That change requires something democratic societies find difficult: sustained attention to invisible problems with long time horizons and diffuse benefits. It requires treating infrastructure not as cost to be minimised but as foundation to be maintained. It requires accepting that the reliable systems inherited from previous generations were not gifts but loans, requiring repayment through continued investment.

The alternative is to wait for the taps to run dry and discover what was always true: that civilisation flows through pipes.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: How vulnerable is Australia’s water infrastructure to cyber attacks? A: Water and sewerage systems rank among the most frequently targeted critical infrastructure sectors, accounting for 30% of all reported cyber incidents according to the 2024 Annual Risk Review. The sector’s reliance on SCADA control systems creates particular vulnerabilities, though specific attack capabilities remain classified.

Q: What happens to hospitals during a major water disruption? A: Hospitals face immediate operational crisis. Dialysis patients require treatment every 48-72 hours; surgical sterilisation becomes impossible; cooling systems for critical equipment fail. Elective procedures halt within hours, while emergency departments simultaneously lose capacity and face increased patient loads from contamination-related illness.

Q: How does climate change affect water infrastructure risk? A: Climate change reduces rainfall reliability while increasing extreme weather events. Infrastructure designed for historical climate patterns faces conditions beyond design parameters. The Productivity Commission notes this creates a temporal mismatch: infrastructure operates on generational timescales while climate conditions shift faster than replacement cycles allow.

Q: What would a national water security framework cost? A: Direct costs remain unquantified, but the Australian Water Association estimates potential GDP losses of $452 billion from water-related events between 2022 and 2050 under current arrangements. The investment required for comprehensive resilience would likely represent a fraction of avoided losses, though benefits would accrue over decades while costs would be immediate.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- Critical Infrastructure Annual Risk Review 2024 - Primary source for cyber incident data and cross-sector interdependency analysis

- Security of Critical Infrastructure Act 2018 - Legal framework governing water sector security obligations

- National Water Reform 2024 Inquiry Report - Productivity Commission assessment of climate impacts on water management

- Australian Water Association Economic Analysis - GDP loss projections from water-related extreme weather

- Indigenous Water Knowledge and Values - Research on traditional water management practices in Australasian contexts

- Australia State of the Environment 2021: Indigenous Water - Federal assessment of Indigenous water governance and cultural values

- Indigenous Principles for Water Quality - Guidelines for incorporating Indigenous knowledge in water quality assessment