When Templates Trump Threats: Australia's Security Blind Spot

The Bondi Beach attack exposed a structural flaw in Australia's counter-terrorism architecture. When threat reality contradicts institutional templates, the system optimizes for legibility over security—with consequences that extend far beyond a single incident.

The Machinery of Forgetting

On 14 December 2025, two men attacked a Jewish community event at Bondi Beach. One held an Indian passport. Both followed ISIS ideology. The father had been investigated by ASIO in 2019 and cleared. India is a QUAD strategic partner—one of Australia’s four closest security allies in the Indo-Pacific.

Within days, seven men of Middle Eastern appearance were detained under counter-terrorism powers. All were released without charge. The government announced a national firearms buyback as its primary policy response. Measures addressing antisemitism arrived later, packaged separately, almost as an afterthought.

The attack’s origin did not match the template. The response did anyway.

This is not a story about intelligence failure, though intelligence failed. It is not a story about racism, though racial profiling occurred. It is a story about what institutions actually optimize for when reality refuses to fit the forms they have prepared. The answer, it turns out, is not security. It is legibility.

When the Map Contradicts the Territory

Australia’s counter-terrorism architecture is sophisticated, well-funded, and structurally incapable of processing certain kinds of threats. The National Terrorism Threat Advisory System operates on a five-tier scale—Not Expected, Possible, Probable, High, Extreme—based on intelligence assessments of attack likelihood within the next twelve months. ASIO employs “structured analytical techniques to test, retest and contest their assumptions.” The system is designed to learn.

But learning requires categories. And categories require boundaries. The Bondi attack crossed boundaries that exist not in law but in institutional cognition.

Consider the cognitive architecture. Australian threat templates have been shaped by two decades of experience. The 2014 Lindt Café siege. The 2017 Brighton siege. The 2019 Christchurch attack, which prompted Australia’s firearms-focused response despite occurring in New Zealand. Each event reinforced a particular threat profile: Middle Eastern appearance, Islamic extremism, lone-wolf methodology, firearms or vehicles as weapons.

The Bondi attackers fit none of these categories cleanly. An Indian national—from a democracy, from a strategic partner, from a country whose diaspora is among Australia’s largest and most economically successful. ISIS ideology—but ISIS as a transnational brand rather than an operational network, adopted rather than recruited. A Jewish community target—fitting the global pattern of rising antisemitism but not the Australian template of random public violence.

The institutional response reveals the template’s power. Seven men detained, all of Middle Eastern appearance, none connected to the attack. This is not incompetence. It is the system doing what it was designed to do: searching for threats where it knows how to look. The detention pattern functioned as what organizational theorists call “defensive routines”—behaviors that protect institutions from having to process information that would require structural change.

The firearms buyback announcement is more revealing still. Australia’s 1996 Port Arthur response—a national firearms buyback following a mass shooting—became the template for “decisive action.” It worked then. It was visible, measurable, politically unifying. It created a script. When Bondi occurred, the script ran again, regardless of whether firearms were the relevant variable. The surviving perpetrator used a knife.

The Geometry of Institutional Vision

Why do institutions revert to templates when templates fail? The answer lies not in individual incompetence but in structural constraints that make certain responses easier than others.

First, templates reduce coordination costs. Australia’s counter-terrorism machinery spans ASIO, the Australian Federal Police, state police forces, the Department of Home Affairs, and the Australia-New Zealand Counter-Terrorism Committee. The National Counter-Terrorism Plan, revised in February 2024, provides operational frameworks precisely because ad hoc coordination is slow and prone to error. Templates are not bugs. They are features that enable large organizations to act coherently.

But coherence comes at a price. The same coordination mechanisms that enable rapid response also constrain adaptive response. Each agency has invested in particular capabilities, particular personnel, particular relationships. The AFP has informants in certain communities. ASIO has surveillance infrastructure calibrated to certain threat profiles. State police have training for certain scenarios. When a threat emerges from outside these prepared positions, the machinery can either adapt—slowly, painfully, with coordination costs that may exceed the response window—or it can apply existing capabilities to the new situation regardless of fit.

Second, templates provide legal cover. Australia’s counter-terrorism laws—Criminal Code Part 5.3 and 5.5, control orders, preventative detention orders—were written with specific threat profiles in mind. The CT Amendment Bill 2023 expanded certain powers but did not alter the underlying categories. When officers detain individuals under counter-terrorism powers, they need reasonable grounds. Templates provide those grounds. “Middle Eastern appearance” plus “proximity to attack location” plus “existing database flags” equals reasonable suspicion—legally defensible even when operationally useless.

The seven men released without charge were not detained because officers were racist. They were detained because the legal-operational system made that detention easier to justify than alternatives. The system optimized for defensibility.

Third, templates serve political needs that may diverge from security needs. Politicians face electoral cycles. Bureaucrats face budget cycles. Both face media cycles measured in hours. A firearms buyback is visible, comprehensible, and recalls a successful precedent. An admission that the threat profile has shifted in ways that implicate a strategic partner is none of these things.

India’s position in QUAD creates what intelligence professionals call a “collection gap”—not a technical limitation but a political one. Information about Indian nationals is harder to act upon because acting upon it has diplomatic costs. The membership requirement for alliance information-sharing introduces constraints that prevent sharing data about citizens of partner nations. The very act of formalizing security cooperation creates blind spots within that cooperation.

The Antisemitism Afterthought

The sequencing of policy responses reveals institutional priorities more clearly than any official statement. Counter-terrorism measures came first. Firearms buyback came second. Antisemitism measures came third, announced separately, framed as a distinct policy stream.

This sequencing is not accidental. It reflects a structural separation in Australian policy architecture between “universal” counter-terrorism (which protects everyone from violence) and “particular” community protection (which protects specific groups from targeted hatred). The separation has bureaucratic logic. Different agencies, different budgets, different ministers. But it also has cognitive consequences.

The Special Envoy to Combat Antisemitism was established in July 2024, five months before the Bondi attack. Jillian Segal’s plan, released in July 2025, addresses the fact that “since 7 October 2023, antisemitism has risen to deeply troubling levels.” The plan exists in a separate policy stream from counter-terrorism. Different reporting lines. Different metrics. Different stakeholders.

This separation means that an attack targeting Jews for being Jews gets processed through two systems that do not naturally communicate. The counter-terrorism system sees “terrorism”—a universal threat requiring universal response. The antisemitism system sees “hate”—a particular threat requiring particular response. Neither system is designed to see what the Bondi attack actually was: both simultaneously.

The result is policy that addresses each half of the problem while missing the whole. Counter-terrorism measures that do not specifically protect Jewish communities. Antisemitism measures that do not integrate with threat assessment. Two bureaucracies, each doing their job, together producing a response that no one designed and no one wanted.

The QUAD Paradox

The Bondi attack exposes a structural tension in Australia’s security architecture that extends far beyond this single incident. Australia’s strategic posture increasingly depends on the QUAD—the quadrilateral partnership with the United States, Japan, and India. This partnership is built on shared threat perception, primarily regarding China. It requires information sharing, operational coordination, and diplomatic alignment.

But what happens when a threat originates from within the partnership?

The answer is not conspiracy or cover-up. It is something more mundane and more troubling: institutional incapacity. The systems designed to process threats from adversaries cannot easily process threats from allies. The diplomatic channels that enable security cooperation become constraints on security action. The shared threat perception that justifies the alliance becomes a filter that screens out threats that do not fit the shared frame.

The Bondi perpetrator’s Indian nationality is not incidental. It is structurally significant. An Australian security response that highlighted Indian-origin terrorism would create diplomatic friction with a QUAD partner at a moment when QUAD cohesion is a strategic priority. This does not mean anyone ordered a cover-up. It means that every official making every decision faced incentives that pointed away from emphasizing the Indian connection and toward emphasizing other aspects of the attack.

The ISIS ideology provides a useful alternative frame. ISIS is a known threat, an established category, a template that works. Framing Bondi as an ISIS attack rather than an Indian-origin attack requires no new categories, no diplomatic complications, no structural adaptation. The fact that ISIS as an organization had no operational connection to the attack is less important than the fact that ISIS as a category fits the existing machinery.

What Institutions Actually Optimize

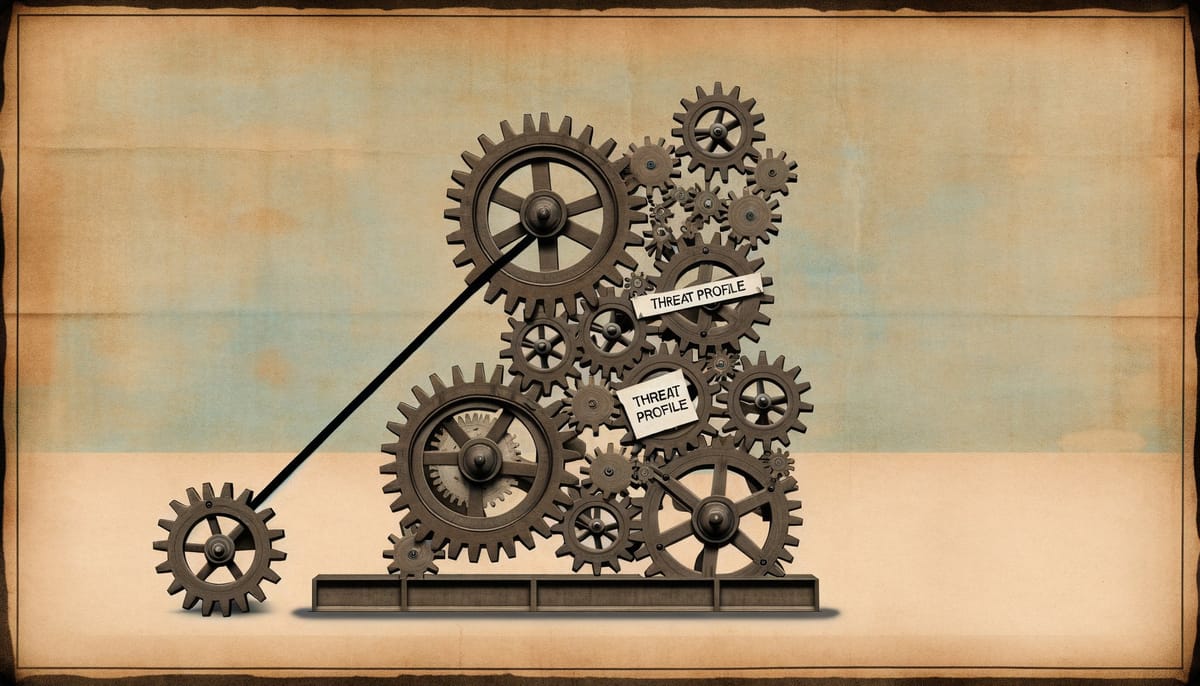

The Bondi case study suggests a general principle: when threat reality contradicts threat template, institutions optimize for template preservation rather than threat response.

This is not cynicism. It is structural analysis. Templates represent accumulated institutional investment—training, equipment, relationships, legal frameworks, political capital. Abandoning a template means writing off that investment. Adapting a template means incurring coordination costs across multiple agencies with different interests. Preserving a template means doing what the system already knows how to do, even when what the system knows how to do is not what the situation requires.

The optimization function is not “minimize threat” but “minimize institutional disruption while appearing to minimize threat.” These are not the same thing. They can diverge dramatically, as Bondi demonstrates.

ASIO’s 2024 Annual Threat Assessment acknowledged that “while Australia’s terrorist threats have reduced in scale, they have increased in complexity.” Director-General Mike Burgess noted that “threats to our way of life have surpassed terrorism as Australia’s principal security concern.” The institutional awareness exists. The structural capacity to act on that awareness does not.

The January 2025 Counter-Terrorism and Violent Extremism Strategy “outlines the steps the Government is taking and will take into the future to respond to the evolving threats of terrorism and violent extremism.” It details “changes to the terrorist threat environment since 2022, including the raising of the National Terrorism Threat Level to ‘PROBABLE.’” The language acknowledges evolution. The structure remains unchanged.

The Path Not Taken

What would a different response have looked like?

First, it would have required immediate acknowledgment that the attack’s origin—a QUAD partner nation—was analytically significant, not diplomatically inconvenient. This would have meant briefing Indian counterparts directly, requesting cooperation on the perpetrator’s radicalization pathway, and publicly framing the attack as a shared problem requiring shared response. The diplomatic cost would have been real but manageable. The analytical benefit would have been substantial.

Second, it would have required integrating antisemitism response into counter-terrorism response from the first hour, not the first week. The Special Envoy’s office should have been in the crisis response room, not waiting for a separate policy announcement. This would have required structural changes that do not currently exist: reporting lines that cross agency boundaries, budgets that can be deployed flexibly, personnel with dual expertise.

Third, it would have required resisting the firearms buyback reflex. Not because firearms policy is unimportant, but because announcing it as the primary response to a knife attack signals that the institution is running a script rather than analyzing a situation. The political cost of not announcing a firearms buyback would have been real. The analytical benefit of demonstrating adaptive capacity would have been substantial.

None of this happened. None of it was likely to happen. The structural constraints that prevented adaptive response are not bugs in the system. They are the system.

The Forecast

Australia will face more attacks that do not fit existing templates. The globalization of extremist ideology means that threat profiles will increasingly cross the boundaries that institutions use to organize their work. ISIS ideology can be adopted by anyone with internet access. Antisemitic violence can be perpetrated by individuals from any national origin. Strategic partnerships will continue to complicate threat assessment.

The current trajectory leads to a predictable pattern: template-driven responses that address the wrong variables, followed by post-hoc rationalization, followed by the next attack, followed by the same cycle. Each iteration erodes public confidence without improving public safety.

Breaking this cycle would require structural changes that no current political incentive supports. It would require agencies to share not just information but authority. It would require politicians to accept responses that are effective but not visually dramatic. It would require legal frameworks that enable action against threats that do not fit existing categories. It would require diplomatic relationships that can absorb the friction of honest threat assessment.

The alternative is a security apparatus that becomes increasingly sophisticated at addressing threats that no longer exist while remaining structurally blind to threats that do. Australia’s counter-terrorism machinery is not failing. It is succeeding—at optimizing for the wrong objective.

FAQ: Key Questions Answered

Q: Why were seven men detained and released without charge after the Bondi attack? A: The detentions reflected existing threat templates that associate terrorism with Middle Eastern appearance. Officers acted within legal frameworks that make such detentions defensible even when operationally unproductive. The releases indicate the template did not match the actual threat.

Q: What is the connection between QUAD partnership and domestic terrorism response? A: Strategic partnerships create implicit constraints on threat assessment. When a threat originates from a partner nation, the diplomatic costs of acknowledging that origin can exceed the analytical benefits, leading institutions to emphasize alternative framings that fit existing categories.

Q: Why was a firearms buyback announced in response to a knife attack? A: Australia’s 1996 Port Arthur response created a template for “decisive action” that subsequent governments have replicated. The buyback announcement reflects institutional memory and political incentives rather than operational analysis of the specific attack.

Q: How does Australia’s counter-terrorism strategy address evolving threats? A: The January 2025 strategy acknowledges increased threat complexity and raised threat levels. However, the structural separation between counter-terrorism and community protection measures means responses to attacks with multiple dimensions—like antisemitic terrorism—remain fragmented across agencies with different mandates.

The Quiet Machinery

The Bondi attack will fade from public memory. The policy responses will be implemented, evaluated, and eventually superseded. The structural dynamics that produced those responses will remain.

Institutions do not optimize for security. They optimize for institutional survival, which sometimes aligns with security and sometimes does not. When threat reality contradicts threat template, the template usually wins—not because anyone decides it should, but because the accumulated weight of training, equipment, relationships, legal frameworks, and political capital makes template preservation the path of least resistance.

The question is not whether Australia’s security institutions failed at Bondi. By their own metrics, they succeeded: an attack was contained, perpetrators were identified, policy responses were announced, and the system continued functioning. The question is whether those metrics measure what matters.

The answer, for now, is that they measure what institutions are designed to measure. Nothing more. Nothing less. And in the gap between what is measured and what matters, the next attack is already taking shape.