What happens when America's Gulf allies refuse to host Iran strikes

When Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar denied basing and overflight access for operations against Iran, they exposed the fragility beneath four decades of American military investment in the Gulf. The US can still strike—but not sustain a campaign.

🎧 Listen to this article

The Geography of Refusal

In April 2025, when American military planners began preparing strike options against Iranian nuclear facilities, they encountered an obstacle more formidable than Tehran’s air defenses: their own allies. Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar—hosts to approximately 40,000 American troops across eight permanent bases—delivered a unified message through diplomatic channels. Their airspace, their ports, their runways would not be available for offensive operations against Iran.

This was not a negotiating position. It was a statement of fact.

The refusal upended decades of American strategic assumptions in the Gulf. Since the Carter Doctrine of 1980, Washington has treated regional access as a given—a foundation upon which all Middle Eastern military planning rested. That foundation has cracked. When the United States eventually struck three Iranian nuclear facilities in June 2025 during Operation Midnight Hammer, it did so with B-2 bombers flying 12,000 miles from Missouri, not F-15s launching from Qatar. The operation succeeded. But the contortions required to execute it revealed something profound about the changing architecture of American power projection.

The Gulf states have not abandoned their American partner. They have simply discovered that partnership has limits—and that those limits are set in Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, not Washington.

The Bases That Bind

The scale of American military infrastructure in the Gulf defies casual comprehension. Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar serves as CENTCOM’s forward headquarters, hosting over 10,000 personnel and functioning as the nerve center for air operations across the Middle East. Bahrain houses the Fifth Fleet. Kuwait provides the primary staging ground for ground forces. The UAE offers deep-water port access and pre-positioned equipment. Together, these facilities represent four decades of investment in a regional architecture designed for exactly the kind of conflict now contemplated.

Yet the legal foundation beneath this architecture is surprisingly fragile. Unlike NATO allies, Gulf Cooperation Council states generally lack comprehensive Status of Forces Agreements with the United States. Access relies instead on ad hoc permissions, defense cooperation agreements, and operational approvals that can be granted—or withheld—at the discretion of host governments. The 2024 US-Jordan Defense Cooperation Agreement provides a template for what comprehensive access looks like. Most Gulf arrangements fall short.

The distinction matters enormously when hosts decide to exercise discretion.

Why would America’s closest Gulf partners refuse access for strikes against their own regional rival? The answer lies in the 2019 attacks on Saudi Aramco facilities at Abqaiq and Khurais. Iranian drones and cruise missiles struck the heart of the Saudi oil industry, temporarily halving the kingdom’s production capacity. The United States condemned the attack. It imposed additional sanctions. It did not respond militarily.

Mohammed bin Salman drew the obvious conclusion. American security guarantees, however elaborate the infrastructure supporting them, do not extend to absorbing Iranian retaliation on behalf of Saudi Arabia. If hosting American strikes means inviting Iranian missiles, the calculation changes fundamentally. The Crown Prince learned, as regional analysts have noted, that “the UAE will not allow its airspace, territory or waters to be used for hostile actions against Iran.” Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Turkey, and Oman delivered similar messages.

The refusal reflects not weakness but strategic maturity. Gulf states have concluded that their interests diverge from Washington’s on the specific question of kinetic action against Iran. They will continue hosting American forces for deterrence. They will not volunteer as launch pads for a war they did not choose.

Twelve Thousand Miles of Workaround

Operation Midnight Hammer demonstrated what American planners already knew: the United States can strike Iran without Gulf cooperation. The question is what such strikes cost—and what they cannot achieve.

Seven B-2 Spirit bombers departed Whiteman Air Force Base in Missouri on a single evening in June 2025, flying east toward Iran while another group flew west over the Pacific as decoys. The bombers struck Fordow, Natanz, and Isfahan—the crown jewels of Iran’s nuclear program—using penetrating munitions designed for hardened targets. They refueled multiple times en route, requiring tanker support staged from Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean. The round-trip exceeded 30 hours.

The operation succeeded tactically. It also revealed the outer limits of what long-range strikes can accomplish.

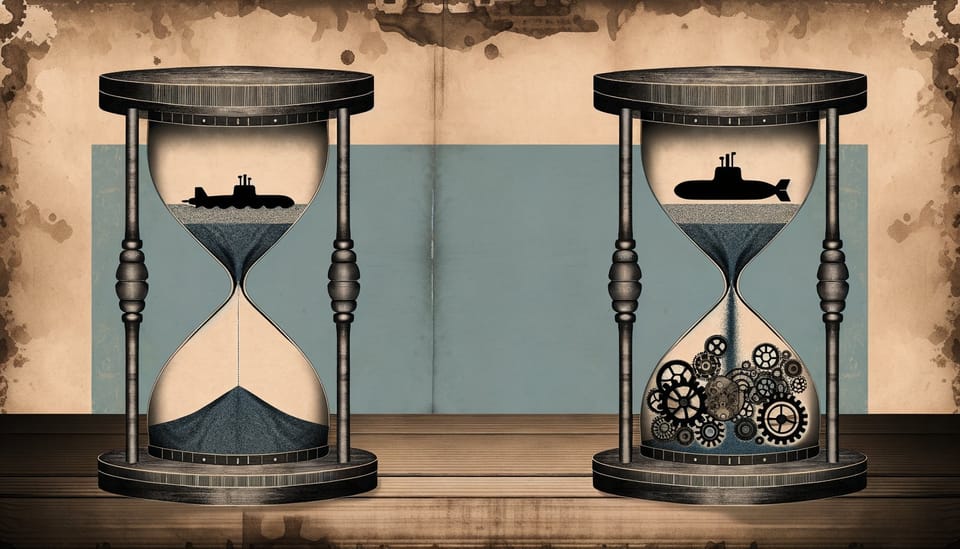

Consider the arithmetic of sustained operations. A B-2 sortie from CONUS requires approximately 40 hours from takeoff to recovery, including transit, refueling, and the strike itself. The Air Force maintains 20 operational B-2s. Even assuming perfect maintenance and crew availability—assumptions that strain credulity—the maximum sustainable sortie rate against Iran from continental bases is roughly one strike package every 48 hours. Compare this to operations from Al Udeid, where F-15E Strike Eagles can generate multiple sorties daily with flight times measured in hours rather than days.

The difference is not merely quantitative. Short-range operations from regional bases enable time-sensitive targeting—the ability to strike mobile missile launchers, leadership compounds, or emerging threats within the narrow windows when they become vulnerable. Long-range bomber operations from CONUS or Diego Garcia cannot achieve this responsiveness. By the time a B-2 reaches Iranian airspace, the target may have moved.

Diego Garcia itself presents complications. The British Indian Ocean Territory lies 2,500 miles from the Persian Gulf, requiring extensive tanker support for any aircraft operating from its runways. More fundamentally, ongoing negotiations over the territory’s sovereignty have introduced uncertainty into American access. The base remains operational, but its long-term status is contested.

Carrier aviation offers an alternative, though not an easy one. A carrier strike group positioned in the Arabian Sea can launch aircraft against Iranian targets without transiting Gulf state airspace. But the Persian Gulf itself—where carriers would need to operate for sustained coverage—presents acute vulnerabilities. Iran maintains “thousands of ballistic missiles and attack drones that threaten every American base and every partner in the Region,” according to CENTCOM’s 2025 posture statement. The Gulf’s confined waters favor Iran’s asymmetric capabilities: fast attack boats, anti-ship missiles, and mines that could turn a carrier deployment into a catastrophic gamble.

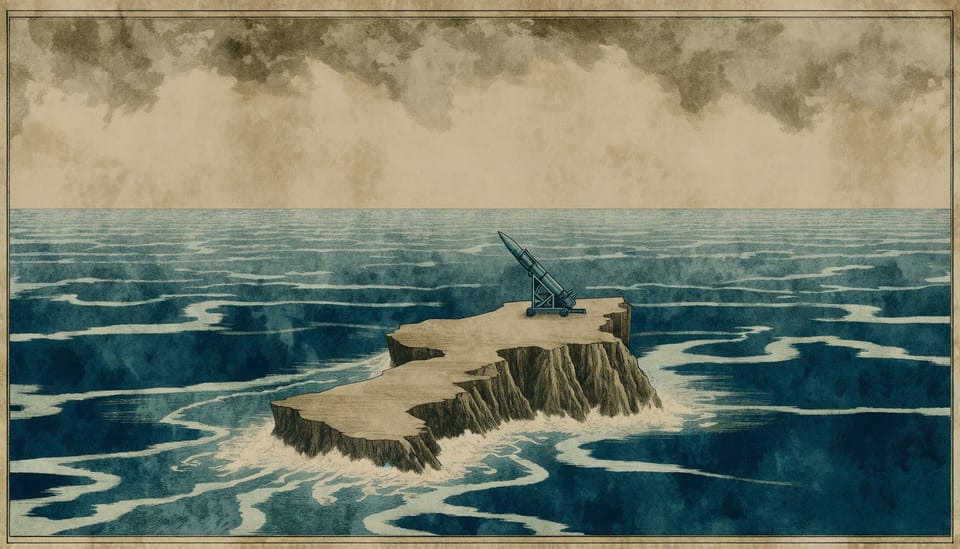

Submarines offer the most access-independent option. Ohio-class guided missile submarines carry up to 154 Tomahawk cruise missiles, can approach launch positions undetected, and require no host nation permission. But cruise missiles cannot penetrate Fordow’s 80 meters of granite. For hardened targets, there is no substitute for manned aircraft delivering heavy ordnance.

The Logistics of Isolation

Striking Iran is one thing. Sustaining a campaign is another.

Modern air operations consume resources at rates that would have astonished planners a generation ago. A single F-15E sortie requires approximately 15,000 pounds of fuel, extensive maintenance between flights, and munitions that cannot be manufactured quickly. The US defense industrial base produced 240,000 artillery shells annually before the Ukraine conflict—barely six weeks of Ukrainian consumption. Precision-guided munitions face similar constraints. A sustained air campaign against Iran would exhaust stockpiles faster than they could be replenished.

Without Gulf basing, the logistics become nearly impossible. Tanker aircraft—the KC-135s and KC-46s that enable long-range operations—require forward bases for efficient employment. Flying tankers from Diego Garcia to support bombers from Missouri creates a logistics chain of absurd complexity, with tankers refueling tankers refueling bombers in an aerial ballet that multiplies every point of failure.

Combat search and rescue presents an even starker problem. When pilots eject over hostile territory, their survival depends on rapid extraction—typically by helicopters staged within range of the combat zone. Without Gulf basing, CSAR capabilities evaporate. The moral calculus shifts: missions that would be acceptable risks with robust rescue coverage become potential death sentences without it. Commanders must either accept higher pilot casualties or restrict operations to reduce exposure. Neither option is palatable.

The Persian Gulf’s physical environment compounds these challenges. High salinity accelerates corrosion on naval vessels. Extreme heat degrades aircraft performance and exhausts maintenance crews. Circadian disruption from transcontinental flights impairs pilot judgment at precisely the moments when judgment matters most. These factors impose hard limits on operational tempo that no amount of planning can overcome.

The Alliance Calculus

Gulf states’ refusal to participate in Iran strikes does not constitute abandonment of the American alliance. It represents a renegotiation of its terms.

The distinction matters. Saudi Arabia continues to purchase American weapons systems. The UAE hosts thousands of American personnel. Qatar maintains Al Udeid as CENTCOM’s forward headquarters. These relationships provide deterrence value, intelligence sharing, and regional influence that Washington cannot easily replace. What the Gulf states have withdrawn is not partnership but complicity in a specific category of operations.

This selective cooperation creates awkward asymmetries. American forces stationed in the Gulf remain vulnerable to Iranian retaliation for strikes launched from Missouri. Host nations bear the risks of proximity without exercising control over the operations that generate those risks. The June 2025 Iranian missile strike on Al Udeid—retaliation for Israeli operations during the broader conflict—demonstrated this dynamic with brutal clarity. Qatar had not authorized the strikes that provoked the response. Qataris died anyway.

Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, Qatar’s Emir, emerged from the 2017 Gulf blockade with a refined understanding of small-state survival. Strategic autonomy, not alignment with regional hegemons, offers the best protection. The Al Udeid attack reinforced this lesson. Hosting American forces provides leverage and protection; hosting American wars provides only exposure.

The broader GCC shares this assessment. Islamic scholars have issued fatwas urging Muslim nations to resist participation in Western military operations against fellow Muslim states. These religious pronouncements carry political weight in societies where legitimacy flows from sources beyond ballot boxes. Gulf rulers must balance American pressure against domestic constituencies, tribal networks with cross-border ties, and regional dynamics that punish perceived collaboration with Western aggression.

Jordan illustrates the constraints. The Hashemite Kingdom has deployed F-15 fighters and KC-135 tankers in coordination with American forces, providing some regional capability outside the GCC framework. But Jordan’s population includes large Palestinian and Iraqi communities with complex relationships to Iranian influence. Tribal constituencies span borders with Iraq and Saudi Arabia. The risks of visible participation in Iran strikes extend beyond Iranian retaliation to domestic destabilization.

Beyond Kinetics

When traditional military options contract, alternatives expand.

Cyber operations offer geography-independent effects that bypass the access problem entirely. American cyber capabilities can reach Iranian nuclear facilities through undersea cables and satellite links without requiring a single aircraft to enter contested airspace. The Stuxnet precedent demonstrated what sophisticated cyber weapons can achieve against centrifuge cascades. Subsequent operations have presumably refined these capabilities.

The limitations are equally significant. Cyber effects tend toward disruption rather than destruction. They can delay Iranian nuclear progress; they cannot eliminate it. And cyber operations carry escalation risks of their own—Iran possesses capable cyber forces that have targeted American infrastructure and allied financial systems.

Economic warfare through expanded sanctions and maritime interdiction offers another vector. Iran’s shadow fleet of tankers—vessels operating under flags of convenience to evade sanctions—provides a target set that requires no Gulf cooperation to engage. The US Navy can interdict Iranian oil shipments in international waters, though doing so risks escalation and imposes costs on the global energy market that American allies may not accept.

The shadow fleet’s evolution reveals the cat-and-mouse dynamics of sanctions enforcement. Complex ownership webs obscure beneficial ownership. Flags of convenience from states like Panama and Liberia provide legal cover. Crews from developing nations bear the risks—and face the choice between unemployment and hauling sanctioned cargo. Tightening this net requires sustained diplomatic effort and maritime presence that competes with other priorities.

What Remains

The United States retains the capability to strike Iran without Gulf cooperation. Operation Midnight Hammer proved this. What it cannot do is sustain the kind of campaign that would fundamentally alter Iranian behavior or capabilities.

A single night of strikes can destroy facilities. It cannot prevent reconstruction. It cannot eliminate dispersed knowledge. It cannot change the strategic calculations that led Iran to pursue nuclear capabilities in the first place. For that, sustained pressure is required—and sustained pressure requires either regional access or resources far exceeding what the United States has demonstrated willingness to commit.

The default trajectory points toward accommodation. Not formal agreement, but tacit acceptance that American options have narrowed and Iranian options have expanded. Gulf states will continue hedging, maintaining American partnerships while cultivating relationships with Beijing that provide alternative security architectures. Iran will continue its nuclear program, calibrating progress to remain below thresholds that might trigger the kind of American response that proved possible in June 2025.

This is not the outcome anyone planned. It is the outcome the geometry of refusal produces.

FAQ: Key Questions Answered

Q: Can the US still strike Iran without Gulf allies? A: Yes, but with severe constraints. Long-range bombers from continental bases and submarines can deliver strikes, but cannot sustain campaigns or respond to time-sensitive targets. The June 2025 strikes demonstrated capability; they also demonstrated limitations.

Q: Why are Gulf states refusing to support Iran strikes? A: Fear of retaliation without American protection. The 2019 Aramco attacks showed that the US would not respond militarily to Iranian strikes on Gulf infrastructure. Hosting American operations means inviting Iranian missiles without guaranteed defense.

Q: What alternatives exist to kinetic strikes? A: Cyber operations, expanded sanctions, and maritime interdiction of Iranian oil exports can impose costs without requiring regional basing. However, these options delay rather than eliminate Iranian capabilities and carry their own escalation risks.

Q: Does this mean the US-Gulf alliance is ending? A: No. Gulf states continue hosting American forces, purchasing American weapons, and cooperating on intelligence. What has changed is their willingness to participate in offensive operations against Iran specifically. The alliance persists; its terms have been renegotiated.

The Quiet Reckoning

Four decades of American military investment in the Gulf rested on an assumption so fundamental it was rarely examined: that access would be available when needed. The assumption was wrong.

This does not mean the investment was wasted. American bases in the Gulf continue to provide deterrence, presence, and influence that no other power can match. They enable counterterrorism operations, maritime security, and the kind of routine military engagement that sustains alliances. What they cannot provide is a launching pad for wars that host nations have decided not to fight.

The geometry of American power in the Middle East has not collapsed. It has revealed its true shape—more constrained than planners assumed, more dependent on host nation consent than basing agreements suggested, more vulnerable to the quiet veto of allies who have learned that partnership need not mean participation.

In Riyadh and Abu Dhabi and Doha, this lesson required no instruction. They have always known that small states survive by choosing their battles carefully. The surprise is that Washington is only now discovering what its allies understood all along.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- CENTCOM 2025 Posture Statement - Official assessment of regional threats and US military positioning

- CBS News Pentagon Briefing on Iran Strikes - Details of Operation Midnight Hammer execution

- US Defense Industrial Base Analysis - Munitions production constraints and surge capacity limitations

- US-Jordan Defense Cooperation Agreement Analysis - Template for comprehensive basing arrangements

- The National News on Gulf State Positions - Regional diplomatic dynamics and access denial

- Backchannel Diplomacy Research - Hidden architecture of international negotiations

- Flags of Convenience Analysis - Shadow fleet operations and sanctions evasion

- Congressional Research Service Iran Report - Comprehensive background on US-Iran policy dynamics