What breaks first when US allies must self-defend: NATO's eastern flank, Taiwan, or the Gulf?

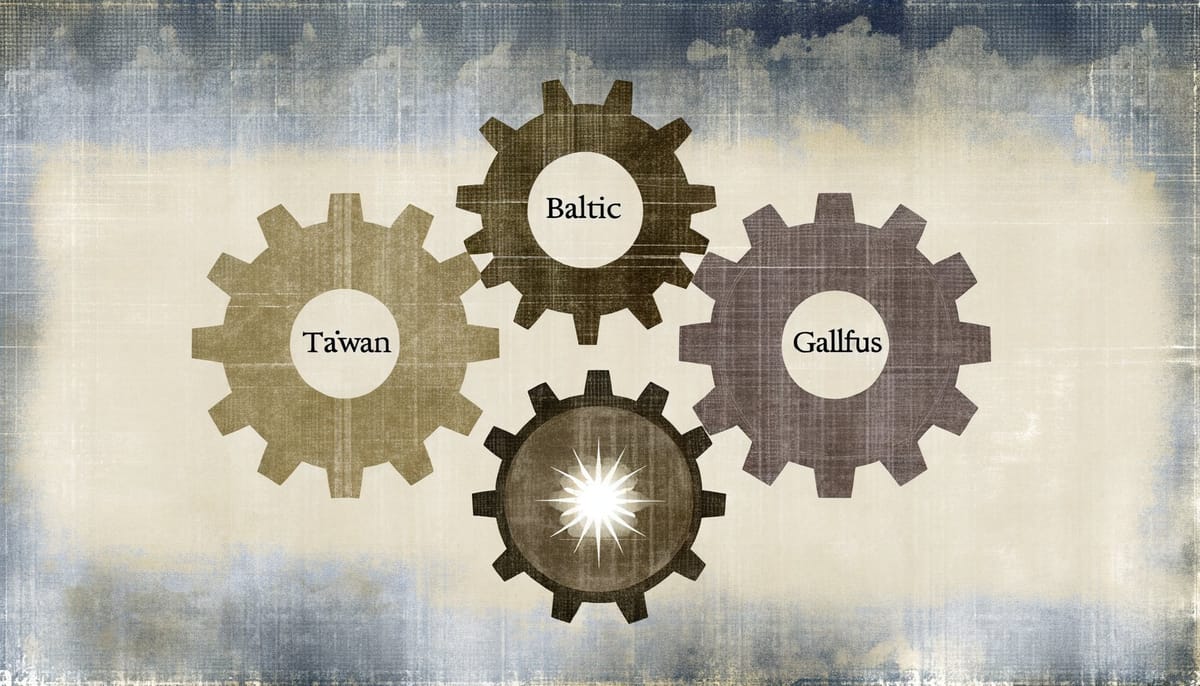

Three allied theaters share a common vulnerability: industrial dependence on American production that no ally has seriously attempted to replicate. When stockpiles determine survival, the question becomes who runs out first.

🎧 Listen to this article

The Weakest Link

Three phone calls, three time zones, three very different anxieties. In Tallinn, defense planners war-game a Russian thrust through the Suwalki corridor. In Taipei, air defense officers track another wave of People’s Liberation Army Air Force jets probing the island’s identification zone. In Riyadh, naval strategists contemplate what happens when the next Houthi missile finds a tanker. Each theater operates on the assumption that American power will arrive in time. Each assumption grows more fragile by the month.

The question of what breaks first when US allies must defend themselves is not hypothetical. It is the organizing anxiety of allied defense ministries from Warsaw to Taipei to Abu Dhabi. And the answer—uncomfortable as it may be—depends less on adversary capability than on allied industrial capacity, political cohesion, and the willingness to spend blood and treasure without American guarantees.

The Illusion of Comparable Vulnerability

Conventional analysis treats these three theaters as separate problems requiring separate solutions. This misses the structural reality: all three share a common dependency on American logistics, intelligence, and industrial output that no ally has seriously attempted to replicate. The Baltic states lack the depth to absorb a Russian assault. Taiwan lacks the interceptor stockpiles to survive a sustained missile campaign. Gulf states lack the integrated command structures to coordinate a credible maritime defense. But these specific deficiencies matter less than the shared vulnerability: none has built the industrial base to fight alone for more than weeks.

Consider the arithmetic. Ukraine fires approximately 6,000 artillery rounds daily while Russia sustains 20,000—rates that exceed Western nations’ entire annual production capacity before mobilization. NATO’s eastern flank allies have watched this dynamic for three years without achieving the production surge necessary to replicate it. Taiwan’s Patriot batteries and indigenous Tien Kung III systems face similar constraints, with interceptor production unable to match the rate at which China could expend precision munitions in a sustained campaign. Gulf states, despite lavish defense budgets, have outsourced so much capability to American contractors that their systems cannot function without American technicians.

The common thread is not geography or adversary but industrial dependency. Whoever runs out of ammunition first loses. And without American production backing allied stockpiles, all three theaters run out fast.

The Baltic Gamble

NATO’s eastern flank presents the starkest immediate vulnerability. The Baltic states—Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania—occupy territory that Russian forces could theoretically overrun before reinforcements arrive. The Suwalki corridor, a 65-kilometer strip of Polish-Lithuanian border separating Belarus from Russia’s Kaliningrad exclave, represents NATO’s most dangerous chokepoint. Close it, and the Baltics become an island.

Poland has responded with the most aggressive military buildup in Europe. Warsaw now spends over 4% of GDP on defense, more than any other NATO member, and has ordered hundreds of tanks, artillery systems, and aircraft. But equipment purchases do not equal combat capability. Training pipelines take years to mature. Maintenance infrastructure requires decades to build. Poland is buying an army it cannot yet operate at full capacity.

The deeper problem is demographic. The Baltic states face population decline that directly constrains military manpower. Estonia’s population has fallen below 1.4 million. Latvia and Lithuania face similar trajectories. These nations cannot field the mass armies that territorial defense against Russia would require. They have opted instead for quality over quantity—professional forces, advanced equipment, total defense concepts borrowed from Finland and Sweden. Whether this suffices against Russian numerical superiority remains untested.

Finland’s NATO accession has transformed the strategic geometry. Helsinki brings a 1,340-kilometer border with Russia, a conscript army of 280,000 wartime strength, and a defense culture forged in the Winter War. Finnish doctrine assumes fighting alone for weeks before allied reinforcement—precisely the scenario NATO’s eastern flank must now contemplate. But Finland’s model requires societal mobilization that other NATO members have not replicated.

The critical variable is not whether NATO’s Article 5 commitment holds but whether reinforcement can arrive before Russian forces achieve their objectives. Soviet-era railway infrastructure in Eastern Europe imposes logistical constraints that NATO has only begun to address. Different rail gauges, limited road networks, and inadequate pre-positioned stockpiles mean that the alliance’s vaunted rapid reaction forces may not be rapid enough.

If American forces are delayed, distracted, or deliberately withheld, NATO’s eastern flank depends on whether Poland and the Baltics can hold long enough for European reinforcement. Current capabilities suggest they cannot. The flank does not break from Russian strength alone—it breaks from allied industrial and logistical weakness that American presence has long masked.

Taiwan’s Interceptor Deficit

Taiwan’s air defense presents a different calculus. The island is not defending against a ground assault through contested territory but against a missile and air campaign designed to achieve air superiority before any amphibious operation begins. China’s strategy does not require conquering Taiwan quickly. It requires preventing American intervention long enough to present the world with a fait accompli.

Taiwan’s layered air defense integrates American-supplied Patriot PAC-3 batteries, Norwegian-American NASAMS systems, and indigenous Tien Kung III missiles. The Tien Kung III offers a cost advantage—approximately one-sixth the price of Patriot interceptors—and travels at Mach 7 compared to Patriot’s slower speeds. Taiwan has formed a fourth Patriot battalion in 2025 and continues expanding indigenous production. But production rates cannot match consumption rates in a high-intensity conflict.

The PLA Rocket Force fields thousands of short- and medium-range ballistic missiles capable of saturating Taiwan’s defenses. A sustained campaign would exhaust interceptor stockpiles within days, not weeks. Taiwan’s air force, despite receiving F-16V upgrades, faces similar attrition dynamics. Pilots cannot be replaced as quickly as aircraft, and grey-zone fatigue from constant PLAAF incursions already strains readiness.

The Taiwan Relations Act commits the United States to provide defense articles “in such quantity as may be necessary to enable Taiwan to maintain a sufficient self-defense capability.” This language creates strategic ambiguity about whether America would actually fight for Taiwan. But the more pressing question is whether Taiwan can fight for itself long enough for that ambiguity to matter.

Taiwan’s conscription reforms—extending mandatory service from four months to one year—address manpower but not the fundamental interceptor deficit. The island’s semiconductor industry, often described as a “silicon shield,” provides economic leverage but not military capability. TSMC cannot shoot down missiles.

The scenario that breaks Taiwan’s air defense is not a single overwhelming assault but sustained pressure that depletes stockpiles faster than they can be replenished. Without American logistics—specifically, the ability to surge interceptor production and delivery—Taiwan’s defense has an expiration date measured in weeks.

The Gulf’s Fragmented Shield

Gulf maritime security operates under different constraints than either European territorial defense or Taiwanese air defense. The threat is not conventional military assault but asymmetric disruption: Iranian mines, Houthi missiles, and proxy attacks designed to raise the cost of shipping through the Strait of Hormuz and Bab el-Mandeb.

The US Fifth Fleet, headquartered in Bahrain, anchors regional security. The Combined Maritime Forces coalition includes 34 nations. The International Maritime Security Construct coordinates patrols. But these structures depend on American command, control, and intelligence. Remove American ISR—the satellites, the P-8 Poseidons, the signals intelligence—and Gulf states lose the awareness necessary to intercept threats before they strike.

Gulf Cooperation Council states have purchased enormous quantities of advanced weaponry. Saudi Arabia alone has spent hundreds of billions on American and European systems. But coup-proofing strategies have fragmented command structures, preventing the integrated air and missile defense that modern threats require. Each monarchy maintains separate military commands, often deliberately weakened to prevent internal threats to regime survival. The result is equipment without interoperability and capability without coordination.

The 2019 Abqaiq-Khurais attacks demonstrated this vulnerability. Iranian drones and cruise missiles struck Saudi oil facilities despite billions in air defense investments. The attack succeeded not because Saudi systems failed but because they were not positioned or integrated to detect threats from unexpected vectors. American Patriot batteries defended against ballistic missiles from the east; the attack came from the north.

Iran’s strategy does not require closing the Strait of Hormuz permanently. It requires demonstrating the capability to do so, raising insurance premiums and shipping costs to levels that achieve economic coercion without direct military confrontation. War risk premiums already reflect this dynamic. Lloyd’s algorithms can effectively close shipping lanes even if GCC navies physically clear mines—financial definitions of insurability override military definitions of safety.

The deeper vulnerability is infrastructure. Gulf states depend on desalination plants for fresh water. A targeted strike on desalination facilities would create humanitarian catastrophe within days, regardless of military outcomes. This creates a hostage situation that conventional military capability cannot resolve.

The Industrial Binding Constraint

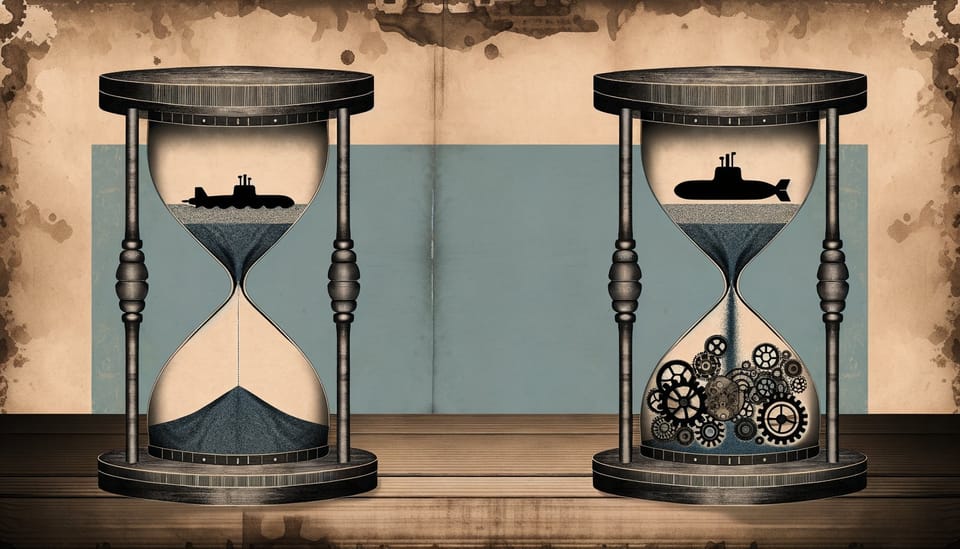

All three theaters share a common constraint: industrial production capacity for precision munitions, interceptors, and spare parts. This is not a political problem susceptible to leadership changes or alliance management. It is a physical limit that determines how long any ally can fight.

Western defense industries optimized for peacetime efficiency, not wartime surge. Just-in-time manufacturing reduced inventory costs but eliminated the slack necessary for rapid production increases. Skilled labor—the machinists, welders, and technicians who build weapons—cannot be trained quickly. Tacit knowledge transmission requires years of apprenticeship. The workforce that built Cold War arsenals has retired. Their replacements were never hired.

China faces different constraints but similar dynamics. Rare earth export restrictions reveal Beijing’s willingness to weaponize supply chains, but also its recognition that industrial capacity determines outcomes. China has invested heavily in domestic semiconductor production precisely because it understands that whoever controls production controls the conflict’s duration.

The United States produced approximately 240,000 artillery shells annually before the Ukraine conflict—barely 40 days of Ukrainian consumption at current rates. Production has increased but remains insufficient to support simultaneous conflicts in Europe, the Pacific, and the Gulf. American allies face the same arithmetic with smaller industrial bases.

This creates a strategic trilemma. The United States cannot surge production fast enough to support all three theaters simultaneously. Allies cannot build independent production capacity quickly enough to substitute for American output. Adversaries understand this and can sequence crises to exploit the gap.

Sequencing and Contagion

The question of what breaks first assumes sequential failure. Reality may prove messier. Actions in one theater instantly reframe risk calculus in others. A Russian move against the Baltics might encourage Chinese opportunism against Taiwan. Iranian escalation in the Gulf might distract American attention from both.

Adversaries understand this dynamic. Russian, Chinese, and Iranian strategic cultures differ enormously, but all three have observed American overextension and drawn similar conclusions. The two-war strategy that once defined American defense planning has become a three-theater problem without corresponding force structure increases.

Cross-theater contagion operates through psychology as much as logistics. Allied confidence depends on perceived American commitment. A failure to respond decisively in one theater undermines credibility in all others. This creates pressure for symbolic responses that may not match strategic priorities—defending everywhere weakly rather than somewhere strongly.

The reverse also holds. Allied self-defense success in one theater could restore confidence across all three. A Baltic defense that holds without immediate American intervention would signal alliance resilience. Taiwanese air defense that survives initial salvos would complicate Chinese planning. Gulf states that coordinate effectively against Iranian harassment would demonstrate capability previously doubted.

What Breaks First

The honest answer is that all three theaters break at roughly the same rate, constrained by the same industrial and logistical dependencies. But if forced to sequence, the analysis suggests Gulf maritime security fails first, followed by Taiwan’s air defense, with NATO’s eastern flank holding longest.

Gulf security breaks first because it lacks the institutional cohesion that NATO provides and the existential stakes that motivate Taiwanese resistance. GCC states have hedged their bets, cultivating relationships with China precisely because they doubt American reliability. This hedging reflects rational calculation but undermines the unified response that effective defense requires. When insurance markets rather than navies determine whether shipping continues, military capability becomes secondary to financial confidence.

Taiwan’s air defense breaks second because interceptor stockpiles cannot survive sustained Chinese pressure without American resupply. Taiwan’s will to fight may prove stronger than Gulf states’ commitment to collective security, but will cannot substitute for missiles. The island’s conscription reforms and indigenous production efforts buy time but do not solve the fundamental consumption-versus-production imbalance.

NATO’s eastern flank holds longest because the alliance possesses institutional depth, industrial capacity (however inadequate), and political commitment that other theaters lack. Article 5’s mutual defense clause creates legal obligations that bilateral agreements do not. European states, whatever their individual weaknesses, can coordinate in ways that Gulf monarchies cannot. Poland’s military buildup, Finland’s accession, and Germany’s belated rearmament suggest trajectory toward adequate capability—eventually.

The Path Not Taken

These outcomes assume current trajectories continue. Alternative paths exist but require choices that allied governments have thus far avoided.

The first intervention point is industrial mobilization. Not procurement increases—actual mobilization of defense industrial capacity to wartime production rates. This requires accepting peacetime inefficiency, maintaining excess capacity, and training workers for jobs that may not exist in normal times. No allied government has made this choice. The political costs of visible military-industrial expansion exceed the perceived benefits of abstract deterrence.

The second intervention point is genuine burden-sharing. Not the 2% GDP spending target that NATO has debated for decades, but actual capability development that reduces dependence on American logistics and production. European strategic autonomy remains aspiration rather than policy. Gulf states continue purchasing American equipment rather than building indigenous capacity. Taiwan has made more progress than either, but from a smaller base.

The third intervention point is alliance integration that transcends individual theaters. NATO, the US-Taiwan relationship, and Gulf security arrangements operate as separate systems. Adversaries coordinate; allies compartmentalize. A unified approach to industrial production, intelligence sharing, and logistics could create resilience that individual theaters lack. No mechanism currently exists to achieve this integration.

The Default Trajectory

Without these interventions, the default trajectory is clear. American retrenchment—whether driven by domestic politics, resource constraints, or strategic choice—will expose allied vulnerabilities that decades of American presence has masked. Adversaries will probe these vulnerabilities, initially through grey-zone operations that avoid triggering formal alliance commitments. Allied responses will prove inadequate, not from lack of will but from lack of capability.

The question is not whether allies can defend themselves but whether they will build the capacity to do so before circumstances force the test. Current evidence suggests they will not. The industrial investments required take decades. The political will required emerges only after crisis. By then, the question of what breaks first will have answered itself.

FAQ: Key Questions Answered

Q: Could NATO defend the Baltic states without US forces? A: European NATO members could likely delay a Russian advance but probably not defeat it without American reinforcement. Poland’s military buildup improves the odds, but logistics constraints and ammunition shortfalls would limit sustained operations. The critical variable is time—whether European forces can hold until political decisions enable full mobilization.

Q: How long could Taiwan’s air defenses last against a Chinese attack? A: Current interceptor stockpiles would likely sustain high-intensity defense for days to weeks, not months. Taiwan’s indigenous production capacity and recent Patriot acquisitions extend this timeline, but not indefinitely. The determining factor is whether American resupply can reach the island during a conflict—a scenario China would actively prevent.

Q: Why can’t Gulf states defend themselves despite massive military spending? A: Gulf Cooperation Council states have purchased advanced equipment but not built the integrated command structures, maintenance infrastructure, or trained personnel necessary to operate it independently. Coup-proofing strategies that fragment military command prevent the coordination that modern air and missile defense requires. The result is capability on paper without effectiveness in practice.

Q: What would change if the US reduced its global military presence? A: Gradual reduction would accelerate allied defense investments but likely not fast enough to close capability gaps before adversaries exploit them. Sudden reduction would trigger immediate crises as adversaries test newly exposed vulnerabilities. The pace of American retrenchment matters as much as its extent.

The Reckoning Deferred

Allied defense ministries understand these dynamics. Internal assessments in Warsaw, Taipei, and Riyadh reach similar conclusions to this analysis. Yet capability investments lag threat timelines. Industrial mobilization remains politically impossible until it becomes strategically necessary. The gap between what allies know and what they do reflects not ignorance but the difficulty of democratic societies preparing for wars they hope to avoid.

The question of what breaks first may ultimately prove less important than whether anything holds at all. Allied security has rested on American guarantees for so long that the institutional memory of independent defense has atrophied. Rebuilding it requires not just equipment purchases but strategic culture change—the recognition that security cannot be outsourced indefinitely.

That recognition is coming. The only question is whether it arrives before the test.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- NATO Washington Summit Declaration - foundational document on Article 5 commitments and eastern flank posture

- Taiwan’s Missile Programs Analysis - detailed assessment of indigenous air defense capabilities

- US-Bahrain Security Cooperation - framework for Gulf maritime security arrangements

- Taiwan Export Control System - technical analysis of defense industrial constraints

- FinCEN Advisory on Iranian Oil Smuggling - documentation of sanctions evasion and maritime threats

- China Rare Earth Export Restrictions - supply chain vulnerability analysis

- European Parliament Analysis of Rare Earth Restrictions - policy implications for defense industry

- Content Analysis in War Coverage Research - methodology for assessing conflict reporting