What breaks first when America deprioritizes China: Allied trust or allied capacity?

The 2026 National Defense Strategy has reordered American priorities, placing homeland defense ahead of comprehensive China containment. For allies who restructured their security postures around sustained confrontation with Beijing, the shift does not merely alter strategy—it questions the...

🎧 Listen to this article

The Legitimacy Collapse

When Australia’s defense minister arrives at the Pentagon this autumn, she will face a question that no talking points can answer: why should Canberra continue spending billions on submarines designed to counter a threat that Washington no longer treats as primary? The 2026 National Defense Strategy has reordered American priorities, placing homeland defense ahead of comprehensive China containment. For allies who restructured their entire security postures around the assumption that America would lead an indefinite confrontation with Beijing, this shift does not merely alter strategy. It questions the legitimacy of every sacrifice already made.

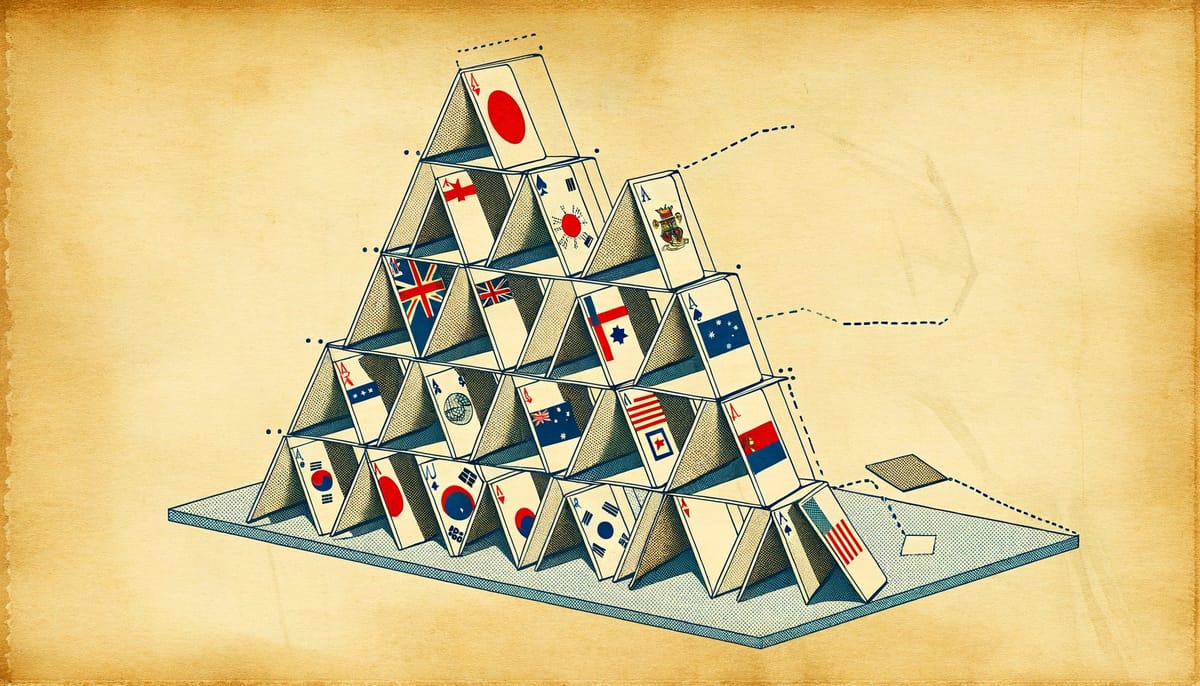

The fracture will not begin with a dramatic withdrawal or a broken treaty. It will start with something quieter: the collapse of what might be called the “fear premium”—the political capital that allied governments accumulated by aligning against China when such alignment carried real economic and diplomatic costs. Australia endured Chinese trade restrictions on barley, wine, and coal. Japan reinterpreted its pacifist constitution to enable collective self-defense. The Philippines accepted domestic controversy over expanded American basing rights. Each government spent political credibility on the premise that the United States would sustain its China focus for decades.

Now that premise has been devalued. The sunk costs remain visible; the strategic rationale has shifted. What breaks first is not military capacity or diplomatic ties. It is the domestic political consensus that made alliance cooperation possible.

The Architecture of Assumption

The 2022 National Defense Strategy identified China as the “pacing challenge” requiring urgent action. Allies treated this language as a foundation, not a floor. Japan’s 2022 National Security Strategy explicitly named China as the “greatest strategic challenge.” Australia’s 2023 Defence Strategic Review organized force structure around Indo-Pacific contingencies. South Korea balanced its China-dependent economy against deepening security ties with Washington. The Philippines under Ferdinand Marcos Jr. reversed years of hedging to permit expanded American military access through the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement.

These were not costless choices. China responded with targeted economic coercion. Research from the University of Technology Sydney documents how Beijing weaponized trade dependencies, imposing restrictions that cost Australian exporters billions in lost market access. Japanese firms faced regulatory harassment in China. Philippine fishermen found themselves excluded from traditional waters. Each ally absorbed these costs because the American commitment appeared durable.

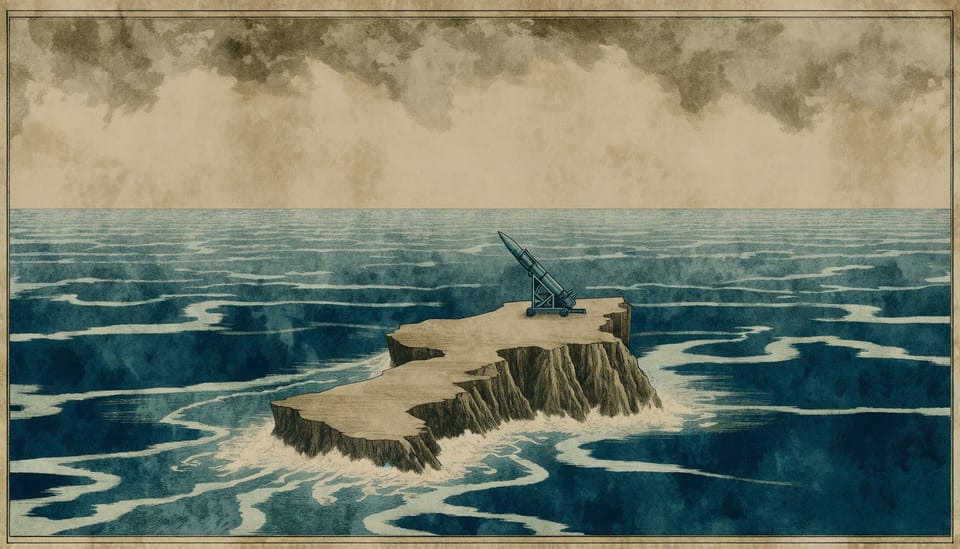

The 2026 strategy changes the calculation. It positions China as the “second priority after homeland/Western Hemisphere” focus, emphasizing “denial defense along First Island Chain” rather than comprehensive containment. For Washington, this represents pragmatic rebalancing. For Tokyo, Canberra, and Manila, it represents something closer to abandonment of the shared strategic framework that justified their sacrifices.

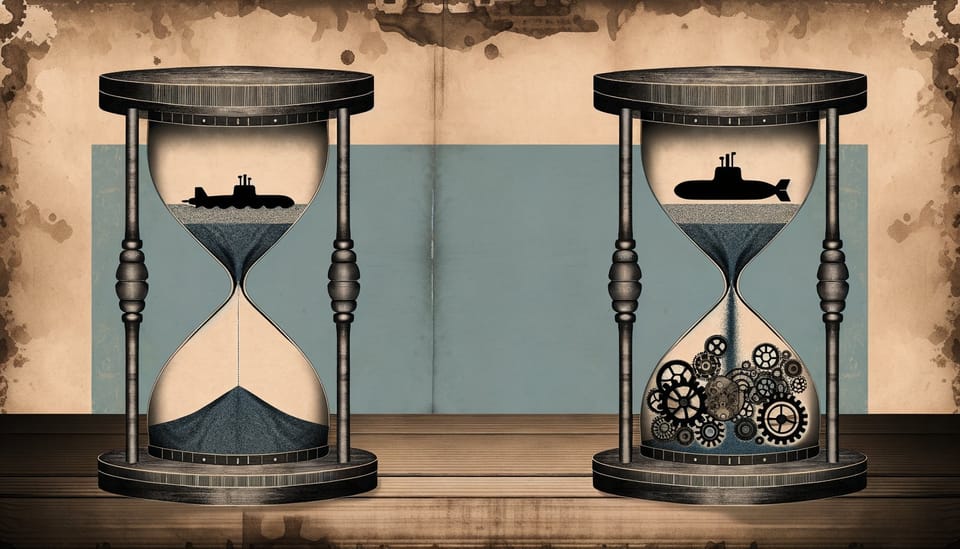

The structural problem runs deeper than rhetoric. Allied defense procurement operates on decade-long timelines. Australia’s AUKUS submarine program, designed to deliver nuclear-powered attack submarines by the 2040s, assumed sustained American commitment to Indo-Pacific dominance. The Joint Leaders’ Statement of March 2023 established the SSN-AUKUS as “a trilaterally-developed submarine based on the United Kingdom’s next-generation design” specifically to counter China’s regional influence. That program now proceeds toward a strategic environment its architects did not anticipate.

Japan’s defense buildup faces similar dissonance. The Kishida government’s reinterpretation of Article 9 to permit collective self-defense was driven partly by American pressure and partly by genuine threat perception. Both factors pointed in the same direction. Now they diverge. The constitutional reinterpretation remains; the American strategic context that justified it has shifted.

The Domestic Fracture

The first visible breaks will occur inside allied governments, not between them and Washington. Every allied leader who championed closer American ties now faces a credibility problem. Opposition parties smell opportunity. Publics who tolerated economic costs for security benefits will demand explanation.

In Australia, the opposition Labor government built its defense policy around AUKUS and China-threat framing. The submarines were sold to voters as essential insurance against regional instability. If that instability no longer commands American priority, the insurance premium looks less justified. Mining interests who lost China market access will ask why they sacrificed profits for an alliance that America now treats as secondary.

Japan’s political dynamics are more complex but equally unstable. The Abe administration’s constitutional reinterpretation created lasting controversy. Pacifist movements never accepted the legitimacy of collective self-defense provisions. They will now argue that the American shift proves their case: Japan restructured its constitutional order to serve American interests that America itself has abandoned. The bureaucratic machinery of Article 9 reinterpretation, which scholars describe as exhibiting “Legalist rigidity,” faces pressure to reverse course—or to accelerate toward genuine strategic autonomy.

South Korea confronts the sharpest dilemma. The country’s security depends on American extended deterrence against North Korea, but its economy depends on China. Seoul has long balanced these dependencies by treating China as a “good threat”—serious enough to justify American alliance, manageable enough to permit economic engagement. Analysis from the Center for Strategic and International Studies notes that South Korea faces “real economic and security retaliation—especially from China—when they engage in deeper cooperation with the United States.”

If America deprioritizes China, South Korea’s balancing act becomes untenable. The threat that justified alliance costs has been downgraded by the alliance leader. Conservative governments that championed American ties face domestic backlash. Progressive governments that favored engagement with China and North Korea gain ammunition.

The Philippines presents perhaps the starkest case. The Marcos government’s decision to expand American basing access through EDCA was domestically controversial from the start. Critics argued it compromised Philippine sovereignty and invited Chinese retaliation without providing proportionate benefits. The 2026 strategy validates their concerns. American forces will use Philippine bases—but for denial defense, not comprehensive deterrence. Manila bears the costs of hosting; Washington limits the commitment.

The Intelligence Fracture

Beyond politics, the operational sinews of alliance cooperation face strain. Five Eyes intelligence sharing—linking the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand—has operated on shared threat assessment. China featured prominently in that assessment. If Washington’s intelligence community now prioritizes homeland threats, the shared picture fragments.

The mechanism is subtle but consequential. Intelligence agencies develop expertise based on collection priorities. Analysts build careers around specific targets. Liaison relationships depend on mutual interest. When one partner’s priorities shift, the others face a choice: follow the leader or develop independent capacity.

For Australia, this choice has immediate implications. The Pine Gap facility, jointly operated with the United States, provides real-time intelligence collection for American combat and counter-terrorism operations. Research on the facility’s role documents its centrality to American global surveillance. But Pine Gap also serves Australian interests—when those interests align with American priorities. If they diverge, Canberra must decide whether to host infrastructure serving American objectives that Australia does not share.

Japan faces analogous questions about missile defense integration. The country’s Aegis systems are deeply integrated with American command and control networks. That integration assumes shared threat perception. If Tokyo perceives China as a more urgent threat than Washington does, the integrated systems may not serve Japanese priorities.

The intelligence fracture extends to threat assessment itself. National Intelligence Estimates have traditionally featured allied commentary as marginal notes on American baseline analysis. Observers have compared this structure to Talmudic commentary—iterative, layered, building on a shared text. When the baseline text changes, the commentary loses coherence.

The Industrial Cascade

Defense procurement cannot pivot quickly. Programs initiated under one strategic framework continue under another. The mismatch creates what might be called “phantom limb pain”—allies continue building capabilities for a threat environment that the alliance leader no longer prioritizes.

Australia’s submarine program exemplifies the problem. The AUKUS agreement commits Canberra to acquiring Virginia-class submarines from the United States as an interim capability, followed by SSN-AUKUS boats in the 2040s. The program assumes sustained American willingness to share nuclear propulsion technology, maintain complex supply chains, and prioritize Indo-Pacific operations. Each assumption now requires reexamination.

The industrial dependencies run both directions. American defense contractors have structured production around allied participation. Lockheed Martin’s F-35 program includes Japanese firms in the supply chain. Raytheon’s missile programs assume allied procurement. If allies reduce orders or redirect investment toward autonomous capabilities, American production lines face disruption.

Analysis of defense procurement markets notes their inherent protectionism—limited buyers, limited sellers, high barriers to entry. When alliance relationships shift, these markets do not adjust smoothly. They seize.

The European dimension compounds the problem. The 2026 strategy explicitly downgrades NATO commitments, characterizing Russia as a “persistent but manageable threat” and demanding 5% GDP defense spending from allies. European governments face their own legitimacy crisis. They justified decades of defense underinvestment partly by relying on American security guarantees. If those guarantees weaken, European publics may demand either dramatic military buildup or accommodation with Russia—neither of which serves American interests.

The industrial cascade connects Indo-Pacific and European theaters. European defense firms have begun exploring partnerships with Asian allies. French naval shipbuilders court Australian contracts. German missile manufacturers eye Japanese procurement. If American reliability declines, these alternative partnerships become more attractive. The alliance system does not merely weaken; it reconfigures around new nodes.

Beijing’s Opening

China will not passively observe allied disarray. Beijing has developed sophisticated tools for exploiting alliance fractures—economic inducements, diplomatic pressure, and information operations calibrated to specific audiences.

Research on Chinese economic statecraft documents how Beijing targets specific industries and constituencies within allied countries. Australian wine producers faced restrictions; barley exporters faced tariffs; coal shipments faced delays. Each measure affected domestic constituencies with political influence. The message was clear: alignment with Washington carries costs.

If Washington itself deprioritizes China, Beijing’s coercion calculus changes. The costs of resisting Chinese pressure no longer purchase American commitment. Allies face a choice between absorbing economic pain for diminished strategic benefit or accommodating Chinese preferences for commercial gain.

The inducement side of Chinese statecraft becomes more potent. Beijing can offer market access, infrastructure investment, and diplomatic recognition to allies willing to distance themselves from American positions. The Belt and Road Initiative provides a framework. Chinese export credit insurance supports firms expanding into markets that American allies once dominated.

Taiwan faces the sharpest version of this dynamic. Taiwanese business and political elites have long calibrated their behavior to American commitment levels. Analysis suggests that hedging increases when faith in American defense commitment declines. If the 2026 strategy signals reduced American willingness to confront China over Taiwan, Taipei’s domestic politics will shift. Accommodation parties gain strength. Independence advocates lose credibility. The cross-strait balance tilts without a shot fired.

The Exercises That Reveal

Military exercises serve as alliance health indicators. Talisman Sabre, the biennial Australia-US exercise, has grown to include multiple partners and scenarios explicitly designed for high-intensity conflict with a peer adversary. The 2025 iteration formally commenced in July, involving forces from over a dozen nations practicing interoperability for Indo-Pacific contingencies.

These exercises reveal both capability and commitment. When American force contributions decline, allies notice. When exercise scenarios shift from offensive operations to denial defense, the strategic message is unmistakable. Chinese military commentary has long criticized Talisman Sabre as destabilizing. Beijing will watch carefully for signs that American enthusiasm has waned.

The exercise calendar also reveals alliance priorities. If Washington redirects forces to homeland defense or Western Hemisphere operations, Indo-Pacific exercise participation suffers. Allies must choose between reduced-scale exercises with American partners or expanded exercises with each other. The latter option—Australia-Japan-India trilaterals, for instance—represents alliance reconfiguration, not alliance maintenance.

The Quad provides a test case. The grouping of Australia, India, Japan, and the United States has institutionalized under American leadership. The 2024 Leaders’ Summit marked continued momentum. But the Quad’s coherence depends on shared China focus. If America deprioritizes that focus, the Quad must either find new purpose or fragment.

India’s position is particularly revealing. New Delhi has approached the Quad instrumentally, extracting benefits while limiting commitments. Analysis indicates that India’s strategic value to the United States is contingent on US-China competition intensity. If that competition cools, India’s leverage diminishes. New Delhi may respond by hedging toward Russia or pursuing truly non-aligned postures.

What Actually Breaks

The sequence matters. First, domestic political consensus fractures within allied governments. Opposition parties exploit the gap between past sacrifices and present American priorities. Publics question why they endured economic costs for an alliance that America now treats as secondary.

Second, procurement programs face cancellation or redirection. Submarines designed for one strategic environment become harder to justify. Missile defense integration loses urgency. Defense budgets face competing demands.

Third, intelligence sharing becomes transactional rather than automatic. Allies develop independent collection capabilities. Liaison relationships cool. Threat assessments diverge.

Fourth, exercises reveal reduced American commitment. Force contributions decline. Scenarios shift. Partners notice.

Fifth, China exploits each fracture. Economic inducements target wavering allies. Diplomatic pressure isolates holdouts. Information operations amplify domestic divisions.

The cascade is not inevitable, but it is probable. Alliance systems depend on shared threat perception. When the leading ally revises that perception, followers must choose between loyalty and self-interest. Most will choose self-interest, gradually, reluctantly, but inexorably.

The First Island Chain strategy that the 2026 NDS emphasizes may prove adequate for American homeland defense. It will not sustain the alliance architecture that previous strategies built. That architecture required allies to believe that America would lead indefinite confrontation with China. They structured their politics, their procurement, and their publics around that belief.

The belief has been withdrawn. The structures remain, for now. But structures without legitimacy are monuments, not fortifications. They mark what was, not what will be.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Does the 2026 National Defense Strategy mean the US is abandoning its Pacific allies? A: Not formally—treaty commitments remain intact. But the strategy shifts from comprehensive China containment to denial defense along the First Island Chain, which means allies can expect reduced American forward presence and greater pressure to provide their own capabilities. The practical effect is a downgrade in commitment level, even if the legal framework persists.

Q: How will AUKUS be affected by America’s strategic shift? A: The submarine program faces significant uncertainty. Australia committed to acquiring Virginia-class boats and developing SSN-AUKUS submarines based on assumptions about sustained American Indo-Pacific focus. If those assumptions no longer hold, Canberra must decide whether to continue a program designed for a strategic environment that Washington no longer prioritizes.

Q: Will Japan develop nuclear weapons if American extended deterrence weakens? A: Japan possesses the technical capability but faces profound constitutional and political barriers. More likely is accelerated conventional buildup and deeper security cooperation with Australia, India, and potentially European partners. Nuclear acquisition would require domestic political transformation that current trends do not suggest.

Q: How is China likely to respond to perceived American retreat? A: Beijing will calibrate pressure and inducement to exploit alliance fractures. Expect targeted economic coercion against allies who maintain close American ties, combined with market access and diplomatic recognition for those who distance themselves. Taiwan faces particular pressure as cross-strait dynamics shift toward accommodation.

The Reckoning

Alliance systems are not contracts. They are ecosystems of shared assumption, mutual sacrifice, and accumulated trust. The 2026 National Defense Strategy does not violate any treaty. It does something more consequential: it reveals that the assumptions underlying allied sacrifices were more contingent than advertised.

Australia did not endure Chinese trade restrictions because Canberra loved Washington. It endured them because Australian leaders believed American commitment would outlast Chinese pressure. Japan did not reinterpret its constitution because Tokyo wanted to please the Pentagon. It did so because Japanese leaders believed American leadership would make collective self-defense worthwhile. The Philippines did not accept domestic controversy over American bases because Manila had no choice. It accepted controversy because Filipino leaders believed American presence would deter Chinese coercion.

Each belief rested on American strategic consistency. That consistency has ended. The beliefs will follow, at varying speeds, with varying consequences, but following nonetheless.

What breaks first is not military capacity or diplomatic ties. It is the legitimacy of alliance itself—the shared conviction that sacrifices made for common purpose will be honored by common commitment. Once that legitimacy fractures, everything else becomes negotiable. And in the Indo-Pacific, everything is about to be negotiated.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- 2026 National Defense Strategy - Primary document establishing the strategic shift analyzed throughout

- CSIS Analysis on Allied Cooperation - Research on alliance dynamics and Chinese economic retaliation risks

- UTS Research on Chinese Economic Coercion - Documentation of Beijing’s trade weaponization against Australia

- MERICS Report on Managing Chinese Coercion - Analysis of Chinese economic statecraft mechanisms

- Geopolitical Monitor on Talisman Sabre 2025 - Coverage of alliance exercise dynamics

- Air University Study on Intelligence Sharing - Research on space-based intelligence cooperation frameworks

- Stimson Center on PRC Economic Coercion - Analysis of Chinese coercion patterns and allied vulnerabilities

- Japan Ministry of Defense White Paper 2023 - Primary source on Japanese threat perception and defense posture