What Breaks First as the Sahel's Security Collapse Spreads to Coastal West Africa?

The crisis spreading from Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger will not arrive at the coast as an invasion. It will come as school absences, shifting market inventories, and the quiet death of institutional legitimacy. Understanding the sequence reveals which interventions might still work—and which...

The Border That Wasn’t

In Benin’s northern Atacora region, teachers have noticed something strange. More children skip school on Mondays and Fridays. The pattern has nothing to do with academic calendars. Families are pulling their children from classrooms to help with household survival as economic pressures mount—and some are simply too afraid to make the journey. What teachers are witnessing, without quite knowing it, is the leading edge of West Africa’s next security collapse.

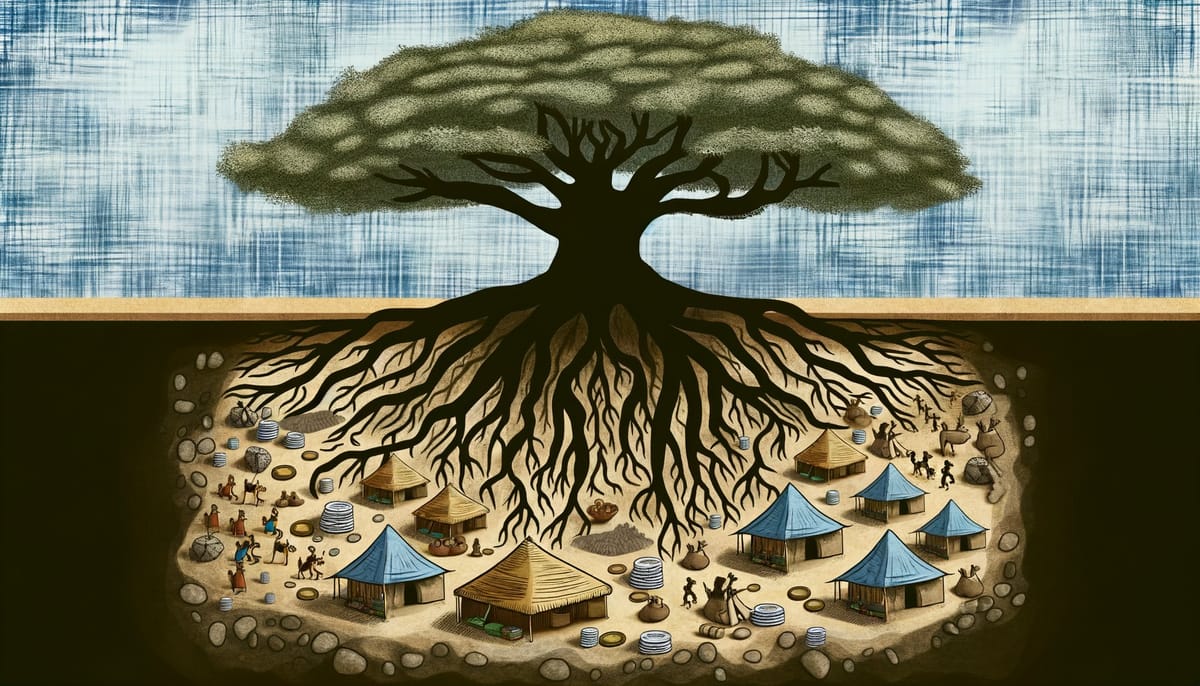

The conventional narrative frames the Sahel’s crisis as a landlocked problem that might, eventually, reach the coast. This gets the dynamics backwards. Coastal West Africa is not waiting to be infected. It is already metabolizing the crisis through systems that operate faster than any military deployment: trade networks, pastoral corridors, informal finance, and the quiet erosion of institutional legitimacy. The question is not whether the coast breaks, but what breaks first—and the answer reveals uncomfortable truths about which structures were load-bearing and which were merely decorative.

The Transmission Mechanism

Violence in the Sahel has killed over 10,000 people in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger in 2024 alone. But counting corpses in the Sahel tells you little about what happens next in Cotonou or Accra. The real transmission mechanism operates through three interlocking systems that predate modern borders by centuries.

The first is pastoral mobility. When Benin banned cross-border transhumance in December 2019, ostensibly to prevent conflict, it did not stop movement. It criminalized it. Herders who once moved cattle along routes their grandfathers used now operate as de facto smugglers, their legitimate grievances weaponized by jihadist recruiters who offer protection the state cannot. ACLED data shows nearly 70% more fatalities in Benin through November 2024 compared to the previous year. The pastoral corridor has become a recruitment pipeline.

The second is informal finance. Hawala networks—trust-based money transfer systems operating outside formal banking—have moved value across the Sahel for centuries. They thrive not despite regulatory weakness but because of it. When formal banking supervision fails in specific corridors, hawala expands to fill the gap. The same networks that allow diaspora remittances to reach villages without bank branches also allow militant groups to move funds across borders that exist only on maps. Attempting to shut down hawala without providing alternatives simply pushes transactions deeper underground.

The third is gold. Artisanal mining operations across the region produce gold that Swiss refineries’ traceability systems are designed to exclude as “conflict gold.” The perverse result: miners in areas controlled by Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) must route their product through informal Dubai channels, which paradoxically increases JNIM’s taxation leverage. The group does not need to control the mines. It needs only to control the chokepoints through which gold must pass.

These systems share a crucial feature: they accelerate under pressure. Sanctions, border closures, and formal enforcement do not eliminate flows—they redirect them through channels that armed groups can tax. The immune response feeds the pathogen.

What ECOWAS Actually Lost

On January 29, 2025, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger formally withdrew from the Economic Community of West African States. The immediate analysis focused on diplomatic rupture and the failure of sanctions to reverse coups. This misses the structural damage.

ECOWAS was never primarily about economics. Its core function was providing a legal architecture for cross-border cooperation that individual states could not create bilaterally. The 1979 Protocol on Free Movement allowed citizens of member states to move, reside, and work across borders—a framework that formalized what pre-colonial populations had done for millennia. The protocol did not create mobility. It legitimized it.

With the Alliance of Sahel States (AES) withdrawal, that legitimacy enters a quantum state. The protocol remains nominally valid for remaining members but practically unenforceable at newly hardened borders. Border officials now possess a tool for arbitrary discretion: they can invoke the protocol’s continued validity or its practical suspension depending on whom they face and what they want. The rule exists and does not exist simultaneously, collapsing into whichever state serves the officer’s immediate interest.

This matters because legitimacy, once lost, does not return on command. The ECOWAS Court has delivered 775 cases. Significant portions remain unenforced. For international legitimacy metrics, the court functions—cases are processed, judgments issued. For anyone seeking actual remedy, it does not. Coastal states now face a choice: maintain the fiction of regional legal architecture or acknowledge that enforcement depends entirely on bilateral relationships with regimes that consider them hostile.

The one-year withdrawal notice period mandated by ECOWAS Treaty Article 91 created something worse than immediate rupture. It produced a legally-defined temporal zone where extradition protocols remained nominally active but functionally unenforceable. Militants who established sanctuary during this window now operate in jurisdictional grey zones that will take years to resolve—if they can be resolved at all.

The Legitimacy Arbitrage

Jihadist groups in the Sahel have discovered something that development economists missed: governance is a service, and services can be competed for.

JNIM’s application of Islamic jurisprudence to farmer-herder disputes creates formalized, predictable resource access rules. This is not ideology for ideology’s sake. It is climate adaptation infrastructure. Traditional customary systems depended on resource abundance—when water and grazing land were plentiful, informal negotiation sufficed. Climate stress eliminated that margin. JNIM offers what the state cannot: predictable rules that both parties know will be enforced.

The mechanism is elegant in its brutality. Sharia-based conflict resolution does not require the group to control territory permanently. It requires only that the group’s rulings be more reliable than the state’s. In northern Benin and Togo, state presence is episodic. A gendarmerie patrol passes through; a development project arrives and departs; a politician visits before elections. JNIM’s presence is continuous. The comparison is not between good governance and bad governance. It is between governance and its absence.

This creates what might be called legitimacy arbitrage. States that cannot provide consistent services across their territory cede ground to actors who can. The transaction is not ideological conversion—most farmers and herders have no interest in global jihad. It is practical submission to whoever can adjudicate disputes without a six-month court backlog.

Coastal states face this dynamic in nascent form. Their northern regions—Benin’s Atacora and Alibori, Togo’s Savanes, Ghana’s Upper East and Upper West—share the structural vulnerabilities that made the Sahel fertile ground: youth unemployment, weak state presence, farmer-herder tensions exacerbated by climate change, and borders that exist primarily as lines on maps. The difference is not immunity but timing.

The Intelligence Gap No One Discusses

Western intelligence frameworks struggle with the Sahel because they are designed to detect organizations, not systems. A JNIM cell can be mapped, targeted, degraded. The pastoral networks that allow recruitment, the hawala channels that move funds, the gold routes that generate revenue—these are not organizations. They are infrastructure. Destroying a node does not disable the network. It reroutes traffic.

The most valuable intelligence in coastal West Africa does not come from signals intercepts or drone surveillance. It comes from market women.

Traders in regional markets adjust their inventory composition in response to information that never reaches formal intelligence channels. A shift from perishable to non-perishable goods signals anticipated disruption. Changes in which currencies traders accept reveal confidence in state stability. The cassava price volatility coefficient of variation—51.5%—functions as a thermodynamic indicator of social disorder. Price swings measure energy being dissipated through a system under stress.

Market women are not intelligence assets. They are distributed sensors operating a parallel information system that states have never learned to read. Their inventory decisions aggregate knowledge about road safety, border crossings, currency stability, and local power dynamics that no single observer could possess. When traders in Parakou begin stockpiling fuel in plastic containers, they are not speculating. They are pricing in disruption that formal systems have not yet detected.

The same logic applies to student absenteeism patterns. Teachers in Atacora observing increased absences due to “household responsibilities” and “lack of interest” are witnessing pre-violent extremist territorial control indicators. The security incident has not yet occurred. Its preconditions have.

What Breaks First

The topology of collapse follows a predictable sequence, though the timing remains uncertain.

First: Cross-border trade formalization. Formal trade between coastal states and the AES bloc is already declining. The ECOWAS breakup threatens food security because the Sahel depends on coastal ports for imports while coastal states depend on Sahelian markets for exports. IFPRI analysis shows this interdependence was already fragile; the political rupture accelerates its unwinding. Informal trade will continue—it always does—but it will operate through channels that states cannot tax and armed groups can.

Second: Border security coherence. Coastal states currently cooperate on border security through ECOWAS frameworks. With those frameworks degraded, bilateral arrangements must substitute. But bilateral arrangements require trust, and trust requires reciprocity. Ghana cannot offer Burkina Faso security cooperation while ECOWAS sanctions remain nominally in force. The result is a patchwork of informal understandings that cannot be institutionalized, formalized, or scaled.

Third: Security sector legitimacy. As threats increase and resources remain constrained, security forces face impossible choices. Historical patterns show that gendarmeries under overwhelming stress default not to innovation but to colonial violence protocols—the institutional memory they possess when adaptive knowledge fails. Checkpoints designed for control become extraction points. The security sector begins to resemble the threat it was meant to counter.

Fourth: Urban stability. Coastal capitals have absorbed over 143,000 refugees and asylum-seekers from the Sahel crisis as of May 2024—a 17% increase in just two months. UNHCR data shows Côte d’Ivoire hosting 52,936, Togo 48,015, Ghana 23,142, and Benin 19,713. These numbers will grow. Urban systems designed for different populations face metabolic stress: housing, water, sanitation, employment. The refugee is not the problem. The system’s inability to adapt is.

The sequence is not inevitable. But altering it requires interventions that current frameworks cannot deliver.

The External Actor Trap

France withdrew from Mali, then Burkina Faso, then Niger. Russia’s Africa Corps filled some of the vacuum. The United States has a ten-year strategy for coastal West Africa that correctly identifies the problem—social cohesion, government responsiveness, security force accountability—but operates on timelines that events have already overtaken.

The strategy’s theory of change is elegant: strengthen social cohesion, improve government responsiveness, enhance security accountability, and populations will promote peace. The flaw is temporal. The strategy assumes a decade to build institutions. Jihadist groups are offering dispute resolution now. The competition is not between Western values and extremist ideology. It is between slow institution-building and fast service delivery.

Russian disinformation compounds the problem by framing Western health and development programs as biological testing on Africans. This does not merely criticize Western assistance. It transforms health infrastructure from development asset into perceived colonial contamination. Vaccination campaigns become evidence of malign intent. The disinformation does not need to be believed by majorities. It needs only to create sufficient doubt that cooperation becomes politically costly.

External security assistance faces a structural paradox. Training programs designed to professionalize militaries create dependencies on the political survival of the officers being trained. French military cooperation explicitly structured around “regime defense” meant that trainers’ mission continuity depended on the political survival of their counterparts. The trainer cannot advocate for reform that threatens the trainee’s position. The assistance perpetuates what it was meant to transform.

What Would Actually Help

Realistic interventions must accept three constraints: limited resources, contested legitimacy, and compressed timelines. Within those constraints, leverage exists.

Formalize informal intelligence. Market women, truckers, teachers, and health workers possess distributed information that formal systems cannot replicate. The intervention is not recruitment—that would destroy their value—but creating channels through which their observations can reach decision-makers without attribution. A teacher reporting increased absenteeism should not need to know she is providing security intelligence. She needs only a system that notices what she notices.

Decouple trade from politics. The AES-ECOWAS rupture need not mean trade rupture. Informal trade will continue regardless; the question is whether states capture any revenue from it. Creating trade facilitation mechanisms that operate below the political threshold—technical standards harmonization, phytosanitary cooperation, transport corridor maintenance—preserves economic interdependence even as political relations deteriorate. This requires accepting that some cooperation with military regimes is preferable to no cooperation at all.

Invest in dispute resolution alternatives. If JNIM’s competitive advantage is predictable adjudication, the response is not military but judicial. Mobile courts, customary law recognition, and alternative dispute resolution mechanisms that reach populations before jihadist structures do. This is slower than kinetic operations and less satisfying to security establishments. It is also the only intervention that addresses root causes rather than symptoms.

Prepare urban systems for sustained refugee flows. The 143,000 already arrived are the beginning. Planning that assumes the crisis will end and populations will return is planning for a world that will not exist. Coastal cities need infrastructure investment scaled for permanent population increases, not temporary humanitarian response.

Each intervention has costs. Formalizing informal intelligence risks compromising sources. Decoupling trade from politics means accepting regimes that violate democratic norms. Investing in dispute resolution diverts resources from security forces. Preparing for permanent refugees means admitting the Sahel is lost for a generation.

These are not pleasant trade-offs. They are the only trade-offs available.

FAQ: Key Questions Answered

Q: Which coastal West African country is most at risk from Sahel spillover? A: Benin faces the most immediate threat, with ACLED recording nearly 70% more conflict fatalities in 2024 compared to 2023. Its northern regions share direct borders with Niger and Burkina Faso, and its 2019 transhumance ban created grievances that jihadist recruiters have exploited.

Q: What is the Alliance of Sahel States (AES) and why does it matter? A: The AES is a mutual defense pact formed in 2023 by the military governments of Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger. Their formal withdrawal from ECOWAS in January 2025 fragmented West Africa’s regional security architecture, creating jurisdictional gaps that armed groups can exploit.

Q: How do jihadist groups fund their operations in West Africa? A: Primary revenue streams include taxation of artisanal gold mining, control of smuggling routes (including tramadol and other contraband), and “protection” fees from communities. Sanctions and border controls often increase their leverage by pushing trade into informal channels they can tax.

Q: Can external military assistance stabilize coastal West Africa? A: External assistance faces structural limitations: training programs create dependencies on incumbent officers, timelines measured in years compete against jihadist service delivery measured in weeks, and Russian disinformation has made Western cooperation politically costly. Assistance can help but cannot substitute for domestic institutional capacity.

The Quiet Collapse

The Sahel’s security failure will not announce itself when it arrives at the coast. There will be no invasion, no dramatic border crossing, no single event that marks the transition from stability to crisis. The arrival will look like increased school absenteeism in Atacora. Like market women shifting inventory from perishables to dry goods. Like border checkpoints becoming extraction points. Like disputes that once went to customary authorities going instead to men with guns and Qurans.

Coastal West Africa’s institutions were never as strong as their democratic credentials suggested. They were load-bearing only in the sense that nothing had tested them. The test is arriving now, transmitted through systems that predate the states themselves and will outlast whatever interventions the international community manages to mount.

What breaks first is not a building or a border or a government. It is the belief—held by farmers and herders and traders and teachers—that the state can be relied upon to adjudicate disputes, maintain order, and provide the minimum conditions for survival. Once that belief breaks, everything else follows.

The Sahel learned this lesson. The coast is learning it now.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- ACLED Conflict Watchlist 2024: Sahel - Comprehensive conflict data showing fatality trends and violence patterns across the Central Sahel

- IFPRI: The ECOWAS Breakup and Food Security - Analysis of trade interdependencies and food security implications of regional fragmentation

- UNHCR West and Central Africa Situation - Refugee and displacement statistics for coastal host countries

- U.S. Strategy for Coastal West Africa - Ten-year strategic framework identifying priority interventions

- Amani Africa: AES Withdrawal from ECOWAS - Documentation of withdrawal process and institutional implications

- GSDRC: Security Sector Evolution - Research on how security institutions transform under stress

- ECOWAS Protocol on Free Movement - Original protocol text establishing regional mobility framework