The Window That Won't Close: Russia's Shadow Fleet and NATO's Undersea Vulnerability

Russia's shadow fleet has spent years mapping NATO's undersea cables and pipelines in the Baltic and North Sea. The intelligence is collected. The targets are known. In a crisis, the vulnerability window—measured in weeks of degraded communications and months of repairs—favors the attacker. NATO...

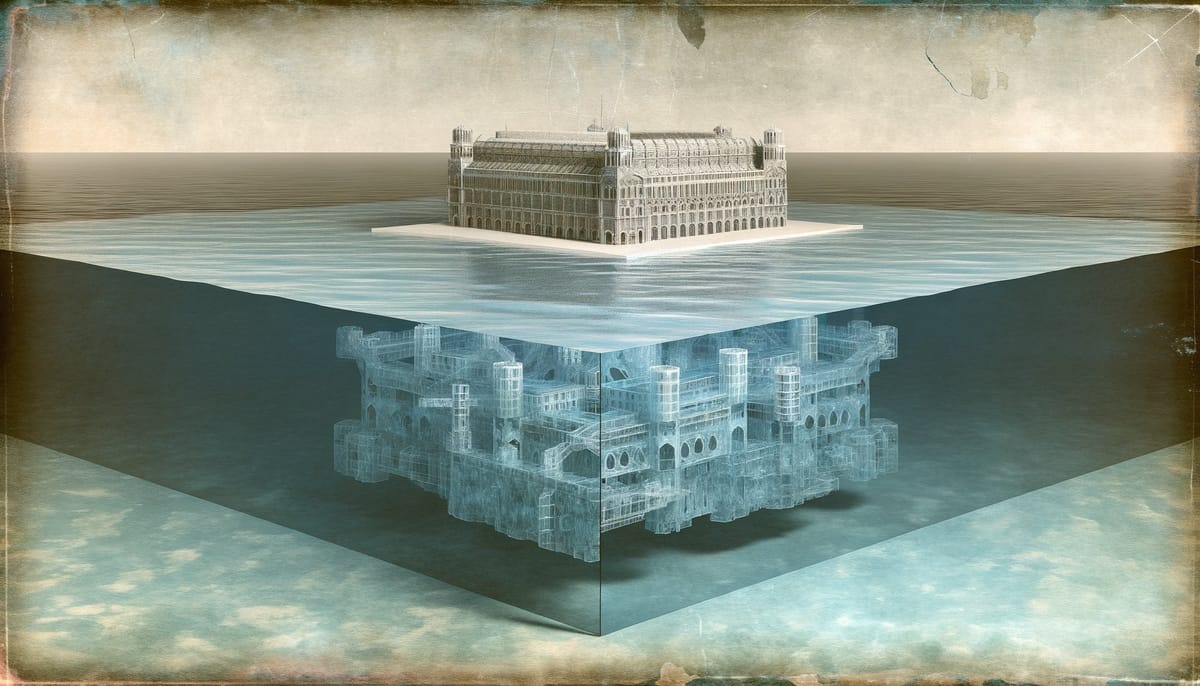

The Map That Precedes the Territory

Russia’s shadow fleet has already done its most dangerous work. The hundreds of aging tankers and cargo vessels that slip through Baltic waters carrying sanctioned oil serve a dual purpose that Western intelligence services have only recently begun to appreciate. According to CNN reporting, Russian personnel with links to military and security services have been “engaged in spying in European waters while working covertly on ships carrying Russian oil.” These vessels don’t merely evade price caps. They chart the seabed. They log the precise coordinates of fiber-optic cables carrying 99% of Europe’s digital communications. They note the burial depths of pipelines. They time patrol patterns and test response protocols.

This peacetime reconnaissance creates a peculiar inversion of conventional military logic. The mapping doesn’t represent vulnerability—it creates it. Before Russia possessed granular knowledge of NATO’s undersea infrastructure, attacks would have been imprecise, easily attributed, and strategically questionable. Now the targeting data exists. The question is no longer whether Russia could cripple Baltic communications in a crisis, but how long NATO would need to restore them—and what happens in the gap.

Anatomy of a Vulnerability Window

The vulnerability window in any Baltic or North Sea crisis operates on three interlocking timescales that favor the attacker.

The first is detection time. NATO’s surveillance architecture has improved markedly since the Nord Stream attacks of 2022. The alliance launched Baltic Sentry in January 2025, deploying frigates, maritime patrol aircraft, and underwater drones to monitor critical infrastructure. Yet detection remains imperfect. Since October 2023, Russia has damaged eleven undersea cables and pipelines in the Baltic Sea, according to the Polish Institute of International Affairs. Several incidents took days to attribute. Others remain officially classified as accidents—a determination that may owe as much to insurance industry timelines as to intelligence certainty. Insurers must classify claims within weeks to pay or deny them; intelligence agencies can afford ambiguity that underwriters cannot.

The second timescale is repair. Industry data indicates median repair times of 30 to 40 days for cable faults, with conventional repairs often taking four to six weeks. This assumes the availability of specialized cable-laying vessels. The global fleet of such ships averages 20 to 22 years old, with many approaching obsolescence simultaneously. A coordinated attack on multiple cables could exhaust repair capacity entirely. The vulnerability window stretches not because damage is irreparable, but because the ships that fix it are few, slow, and predictable in their movements.

The third timescale is political. NATO’s consensus requirement means that invoking Article 5—or even mounting a coordinated response—demands agreement among 32 member states. The alliance’s 2022 Strategic Concept acknowledges that “hybrid operations against Allies could reach the level of armed attack” and trigger collective defense. But no precedent exists for infrastructure sabotage crossing that threshold. Each member calculates differently. The states most dependent on Baltic cables—Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania—would push for rapid response. Those with less direct exposure might counsel restraint. Russia’s entire grey-zone strategy exploits this temporal gap between attack and consensus.

The vulnerability window, then, is not a single duration but a compounding one. Detection takes days. Attribution takes weeks. Repair takes months. Consensus takes however long thirty-two democracies require to agree that an anchor dragged by a Chinese-flagged vessel carrying Russian oil constitutes an act of war.

What Russia Knows

The shadow fleet’s intelligence value lies in its comprehensiveness. These are not occasional reconnaissance missions but sustained presence. Intelligence sources indicate that approximately 50 Russian ships equipped with surveillance and advanced technology operate in Baltic and North Sea waters. Their commercial cover—transporting oil—provides legal justification for their presence in international waters and even territorial seas during transit.

The data they collect goes beyond simple cable locations. Bathymetric surveys reveal burial depths, sediment types, and the precise contours of the seabed. This matters because shallow-water acoustics create complex propagation patterns that affect both detection and attack planning. Research in the Journal of the Acoustical Society of America documents resolution limits of 100 to 200 micrometers in shallow-water imaging—precision that cuts both ways. The same environmental transparency that makes infrastructure easier to locate simultaneously makes detection of approaching threats more feasible. Russia’s mapping advantage lies not in secrecy but in preparation.

The shadow fleet also provides operational security testing. Each transit probes NATO’s response protocols. When does a patrol aircraft investigate? At what distance do frigates intercept? How long before a vessel’s AIS transponder manipulation triggers investigation? The Finnish police’s forensic analysis of an anchor recovered from the Gulf of Finland—now underway—demonstrates that attribution is possible. But the analysis itself creates a temporal constraint. Once forensic examination begins, the deniability window starts closing. Russia’s operational planners now know precisely how long that window remains open.

The intelligence product is not a static map but a dynamic operational template. It includes not merely where to strike but when, how, and with what plausible cover story.

The Cascade Problem

A single cable cut is an inconvenience. Multiple simultaneous cuts become a crisis. The distinction matters because undersea infrastructure exhibits the same cascade vulnerabilities that characterize other networked systems.

Research on interdependent critical infrastructure demonstrates that two independently reliable systems, when coupled through interdependencies, can exhibit unreliable behavior following power-law distributions for cascade sizes. The coupling itself creates vulnerability that doesn’t exist in either system alone. Baltic cables don’t operate in isolation. They interconnect with power grids, financial networks, and military command systems. Degradation in one domain propagates.

Consider a scenario where Russia severs three cables simultaneously during a crisis over the Baltic states. The immediate effect is communications disruption—internet traffic reroutes through remaining capacity, latency increases, some connections fail entirely. But the second-order effects compound rapidly. Financial transactions slow. Energy grid coordination degrades. Military command networks lose redundancy. Each degradation increases load on remaining systems, which increases failure probability, which increases load further.

The economic costs are substantial but quantifiable. The strategic costs are not. NATO’s ability to coordinate a rapid response depends on the same infrastructure under attack. The alliance’s Digital Ocean Vision—its initiative to fuse sensor and data networks for real-time awareness—becomes a liability if the networks themselves are compromised. Defenders face a paradox: the more integrated their command systems, the more vulnerable to infrastructure attack.

Russia need not achieve total communications blackout to accomplish its objectives. It needs only to degrade NATO’s decision-making speed below its own. In a crisis measured in hours, a 48-hour attribution delay is decisive.

The Deterrence Gap

NATO’s official position is that infrastructure sabotage could trigger Article 5. The Washington Summit Declaration of 2024 recognizes “hybrid interference, including sabotage of critical undersea infrastructure like cables, as potential grounds for Article 5 activation if deemed an ‘armed attack.’” The qualifier is load-bearing. “If deemed” means someone must deem it. Thirty-two nations must agree.

This creates what deterrence theorists call a commitment problem. Thomas Schelling’s foundational insight—that effective deterrence requires “the threat that leaves something to chance”—applies inversely here. NATO’s response is not uncertain because of deliberate ambiguity but because of structural incapacity. Russia can calculate, with reasonable confidence, that any given cable attack falls below the threshold for collective defense. The alliance’s own hedging language confirms this.

The Brookings Institution analysis on protecting undersea cables notes the fundamental tension: declaring infrastructure attacks an act of war raises the stakes of every incident, including genuine accidents. Fishing trawlers drag anchors across cables regularly. Declaring such incidents potential casus belli would be absurd. But refusing to draw a clear line invites exploitation.

Russia’s strategy exploits this gap systematically. Each incident tests the threshold. Each non-response establishes precedent. The pattern mirrors what organizational theorists call “normalization of deviance”—the process by which repeated boundary violations become accepted as normal. Research on this phenomenon in high-reliability organizations shows that graduated responses to violations train organizations to accept incrementally greater risk. NATO’s measured responses to each cable incident may be individually rational but collectively corrosive.

The deterrence gap is not merely a failure of signaling. It is structural. NATO cannot credibly commit to treating infrastructure attacks as armed attacks because doing so would require a response mechanism faster than its consensus architecture permits.

The Repair Bottleneck

Even if NATO detected an attack immediately and attributed it within hours, the vulnerability window would remain open for weeks. The limiting factor is physical: there are not enough ships to fix what Russia can break.

The global fleet of cable repair vessels numbers in the dozens. The International Cable Protection Committee maintains a registry, but availability during a crisis would depend on vessel locations, contractual obligations, and the willingness of commercial operators to enter contested waters. A cable repair ship proceeding to a damaged segment in the Baltic during active hostilities becomes a target itself. The documented terrorist tactic of attacking emergency responders—184 such attacks over 50 years according to the Global Terrorism Database—provides a template. The responder becomes the target because their arrival is predictable and their location is constrained by the emergency.

The EU’s Action Plan on Cable Security, adopted in February 2025, allocates €540 million between 2025 and 2027 for digital infrastructure projects, including smart subsea cables. The European Commission’s announcement emphasizes prevention, detection, response, and deterrence. But funding for resilience takes years to materialize as capability. The vulnerability window exists now.

Redundancy offers partial mitigation. Baltic states can reroute some traffic through alternative cables, satellite links, or terrestrial connections. But redundancy degrades under load. Systems designed for backup become primary infrastructure, which increases their failure probability, which reduces redundancy further. The cascade logic applies here too.

The repair bottleneck creates a temporal asymmetry that Russia can exploit. Attacks take hours. Repairs take months. The vulnerability window is not a gap to be closed but a structural feature of undersea infrastructure in its current form.

What Would Change the Calculus

Three interventions could narrow the vulnerability window, each with significant trade-offs.

The first is forward defense. Stationing permanent naval assets near critical cable junctions—not merely patrolling but actively defending—would raise the cost of attack. The Joint Expeditionary Force, led by Britain and including Nordic and Baltic states, has moved in this direction. But forward defense requires sustained presence, which requires resources, which requires political will to maintain during peacetime. The cost of defending every cable junction in the Baltic and North Sea exceeds any plausible budget. Forward defense works only if concentrated on the most critical nodes, which requires acknowledging that some infrastructure is more valuable than others—a determination that itself provides intelligence to adversaries.

The second is attribution speed. The Finnish anchor investigation demonstrates that forensic attribution is possible. Accelerating this process—through pre-positioned forensic capabilities, standardized evidence protocols, and intelligence sharing agreements—could close the deniability window before Russia can exploit it. But faster attribution creates its own pressures. What happens when forensic evidence points unambiguously to a Russian vessel within 72 hours of an attack? The political pressure to respond would be immense. The response options would remain limited. Speed without capability is merely faster frustration.

The third is redundancy investment. The EU’s cable security plan moves in this direction, but the timescales are wrong. New cable routes take years to plan, permit, and construct. Satellite backup systems provide limited bandwidth at higher latency. Terrestrial alternatives require infrastructure that doesn’t exist. The vulnerability window cannot be closed by investments that mature after the crisis has passed.

The most likely trajectory is therefore continued vulnerability. NATO will improve detection, accelerate attribution, and invest in redundancy—all worthwhile measures that nonetheless leave the fundamental asymmetry intact. Russia can attack faster than NATO can respond. The vulnerability window remains open.

The Strategic Implications

Russia’s undersea mapping campaign is not preparation for a specific attack. It is preparation for optionality. The intelligence product enables a range of actions calibrated to different crisis scenarios.

In a limited crisis—say, a dispute over Baltic airspace or a provocation near the Suwalki Gap—Russia could sever a single cable as a demonstration. The message would be clear: we can do this whenever we choose. The response would be constrained by the same factors that constrain response today. The precedent would be set.

In a major crisis—a direct confrontation over the Baltic states—Russia could execute simultaneous attacks on multiple cables, pipelines, and power interconnectors. The objective would not be permanent destruction but temporary paralysis. Degrade NATO’s command networks for 72 hours, and the military balance shifts. Degrade them for a week, and political cohesion fractures.

The shadow fleet’s dual purpose—sanctions evasion and intelligence collection—provides strategic cover. Every vessel is plausibly deniable. Every transit is commercially justified. The mapping continues in plain sight because there is no legal mechanism to stop it. UNCLOS protects the right of innocent passage. Commercial shipping enjoys freedom of navigation. Russia exploits the gap between what international law prohibits (attacking cables) and what it permits (surveying them).

NATO’s vulnerability window is therefore not a temporary condition awaiting a technical fix. It is a structural feature of the current security architecture—one that Russia has systematically mapped and is prepared to exploit.

FAQ: Key Questions Answered

Q: How quickly could Russia disable Baltic undersea cables in a crisis? A: Physical attacks on cables can be executed within hours using anchor-dragging, submersibles, or explosive devices. The constraint is not capability but timing—Russia would likely coordinate attacks with other crisis actions to maximize confusion and delay attribution.

Q: Can satellite communications replace undersea cables if they’re damaged? A: Only partially. Satellite systems provide backup for critical military and government communications but cannot match cable bandwidth for commercial internet traffic and financial transactions. Latency also increases significantly, affecting time-sensitive applications.

Q: What legal options does NATO have against shadow fleet vessels? A: Limited ones. Vessels in international waters enjoy freedom of navigation under UNCLOS. Port states can deny entry or conduct inspections, but shadow fleet vessels typically avoid NATO ports. Sanctions target ownership and insurance, not the physical vessels themselves.

Q: Has NATO invoked Article 5 for infrastructure attacks before? A: No. The only Article 5 invocation followed the September 11, 2001 attacks. Infrastructure sabotage, including the Nord Stream pipeline explosions, has not triggered collective defense despite causing significant damage.

The Window Remains Open

The vulnerability window in a Baltic or North Sea crisis is not a number to be calculated but a condition to be understood. It begins before the first cable is cut—in the years of mapping, the testing of responses, the normalization of near-misses. It extends through the days of detection, the weeks of attribution, the months of repair. It closes only when the last damaged segment is restored and the lessons are absorbed.

Russia has invested heavily in the front end of this timeline. NATO has focused on the back end. The asymmetry is deliberate. The window remains open not because the alliance lacks awareness but because closing it would require capabilities and commitments that peacetime politics cannot sustain.

The shadow fleet continues its transits. The mapping continues. The vulnerability persists. When the crisis comes—if it comes—the window will not close quickly. Russia has ensured that.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- CNN Investigation on Russian Shadow Fleet Espionage - Primary reporting on intelligence personnel embedded in commercial vessels

- Polish Institute of International Affairs - Documentation of eleven Baltic cable and pipeline incidents since October 2023

- European Commission Cable Security Action Plan - Official EU framework and €540 million funding allocation

- Brookings Institution Analysis - Strategic assessment of undersea cable protection challenges

- Carnegie Endowment - Analysis of Russian infrastructure mapping activities

- Finnish Police Forensic Investigation - Ongoing attribution efforts for cable damage incidents

- International Cable Protection Committee - Global cable ship registry and capacity data

- U.S. Army Analysis on Normalization of Deviance - Organizational dynamics of incremental risk acceptance