The Spy Who Couldn't Disappear: HUMINT in the Digital Age

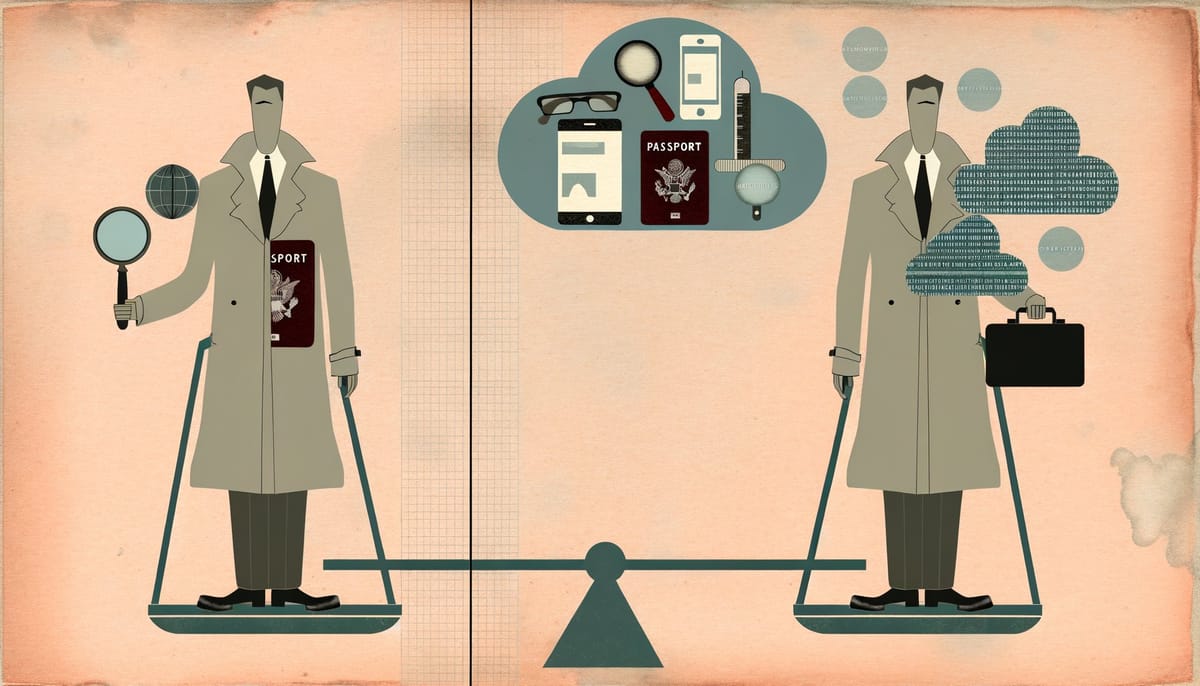

Human intelligence tradecraft has survived every technological revolution from the telegraph to the satellite. The smartphone may be different. In a world where everyone leaves a digital trail from birth, the ancient art of espionage faces its most fundamental transformation.

The Spy Who Couldn’t Disappear

A CIA officer in Moscow once needed only a well-aged passport, a plausible backstory, and the nerve to walk through checkpoints without sweating. Today she needs something far more difficult: a digital ghost that has been breathing for thirty years.

The fundamental challenge of human intelligence has inverted. For centuries, the problem was appearing: constructing a presence convincing enough to penetrate a target. Now the problem is disappearing—or rather, having never appeared at all in the vast digital record that documents every human life from birth to death. A legend without a LinkedIn profile, without a decade of consistent IP addresses, without the metadata exhaust of a life actually lived, is not a legend. It is a beacon.

This inversion has not killed HUMINT. It has transformed it into something the Cold War generation would barely recognize—a discipline where the tradecraft of personal relationships now requires the infrastructure of a technology company and the operational security of a nation-state. The spy who cannot disappear must learn instead to hide in plain sight, surrounded by a carefully constructed digital crowd.

The Death of the Clean Slate

The traditional intelligence legend rested on a simple assumption: strangers could be trusted based on individual presentation rather than kinship verification. This assumption had deep historical roots. West of the Hajnal Line—the demographic boundary running from Trieste to St. Petersburg—late marriage, nuclear families, and geographic mobility created societies where people routinely encountered strangers and evaluated them on their own terms. A man could arrive in Vienna with papers and a story. If both held up under scrutiny, he became who he claimed to be.

That world is gone. The digital age has created what amounts to a continuous kinship verification system, except the kinship is to one’s own past. Every person now trails a twenty-year digital genealogy: email accounts opened in adolescence, social media profiles that document the arc of a life, location data that proves physical presence across thousands of discrete moments. The legend that lacks this genealogy fails not because it triggers suspicion but because its absence triggers automated systems designed to detect exactly this kind of anomaly.

Consider what a backstopped identity now requires. The passport remains necessary but is no longer sufficient. The legend needs social media accounts that show organic growth over years—not just posts, but the pattern of posts, the evolution of writing style, the gradual accumulation of connections that mirrors how actual humans build networks. It needs digital photographs with metadata that places the legend in specific locations at specific times, and those locations must form a coherent life trajectory. It needs the kind of data exhaust that no one thinks about until it is absent: the credit card transactions that prove someone bought coffee in Prague in 2015, the IP addresses that show someone logged into a university network for four years in the early 2000s.

The mathematics are brutal. A legend that would have taken months to construct in 1985 now requires years of patient cultivation—and even then, it degrades. Every platform migration creates forensic inconsistencies. A cover identity built in 2010 has undergone multiple transformations: MySpace to Facebook, HTTP to HTTPS, shifting image formats, evolving metadata standards. Each migration leaves artifacts that betray the legend’s constructed nature to sufficiently sophisticated analysis.

This creates what intelligence professionals call the “digital birth problem.” An officer cannot simply appear at age thirty-five with a complete digital history. That history must have been growing since the officer was a teenager—which means intelligence services must now construct legends for people who have not yet been recruited, maintaining digital identities for years against the possibility that they might someday be needed. The CIA’s Directorate of Operations reportedly maintains thousands of such “pre-legends,” digital identities aging like wine in a cellar, waiting for an officer who may never use them.

The Surveillance Mesh

The construction problem would be manageable if it were the only problem. It is not. The digital age has also transformed the operational environment into what amounts to a continuous surveillance mesh, where every movement generates data that can be retrospectively analyzed.

Start with biometrics. Facial recognition systems now blanket major cities, and their coverage expands monthly. A case officer meeting a source in Shanghai cannot assume the meeting goes unrecorded; she must assume it is recorded and plan accordingly. The meeting location that once offered security—a crowded restaurant, a busy park—now offers the opposite. Crowds mean cameras. Cameras mean faces. Faces mean identification.

The response has been to move meetings to what might be called “biometric shadows”—locations where surveillance coverage is thin or nonexistent. But these shadows are shrinking. Smart city initiatives in Beijing, Moscow, and increasingly in Western capitals are closing the gaps. The Chernobyl exclusion zone, where radiation keeps out both humans and their surveillance infrastructure, has become a dark joke among intelligence professionals: the safest place to meet a source is somewhere too dangerous for anyone to live.

Mobile devices compound the problem. A smartphone is a tracking device that makes phone calls. Even when location services are disabled, the device continues to ping cell towers, connect to WiFi networks, and leave a trail of metadata that can reconstruct its owner’s movements with disturbing precision. Intelligence services have responded by requiring officers to leave devices behind before operational activity—but this creates its own signature. A phone that goes dark for three hours every Tuesday afternoon is not a phone that has been forgotten. It is a phone whose owner has something to hide.

The metadata problem extends beyond devices to the entire infrastructure of modern life. Credit card transactions, transit passes, building access logs, license plate readers—each system generates data that is individually innocuous and collectively devastating. COVID-19 contact tracing apps, originally deployed for public health, created normalized civilian infrastructure for persistent proximity metadata capture. Intelligence services can now query databases to answer a question that was previously unanswerable: who was physically near whom, when, and for how long?

This capability cuts both ways. Western services use it to identify foreign intelligence officers operating under diplomatic cover. Russian and Chinese services use it to identify CIA officers operating under non-official cover. The result is a kind of surveillance equilibrium where everyone knows more about everyone else, and the advantage goes to whoever is willing to aggregate and analyze the most data.

The Recruitment Revolution

If the operational environment has transformed, so has the process of finding and recruiting human sources. The traditional model—spotting a potential source at a diplomatic reception, developing the relationship over months of careful cultivation, making the pitch only when the ground had been thoroughly prepared—has not disappeared. But it has been augmented by something faster and more dangerous.

Social media has created a vast, continuously updated database of potential sources. LinkedIn profiles reveal professional histories, organizational access, and career frustrations. Facebook and Instagram document personal relationships, political views, and psychological vulnerabilities. Twitter shows how people think when they believe no one important is watching. A targeting officer can now develop a detailed psychological profile of a potential source without ever meeting them—and can identify vulnerabilities that would have taken months of personal contact to discover.

The Chinese Ministry of State Security has been particularly aggressive in exploiting these capabilities. MSS officers reportedly use LinkedIn to identify cleared personnel at defense contractors, then approach them through seemingly innocuous professional networking. The approach is deniable, scalable, and devastatingly effective. A single officer can initiate contact with dozens of potential sources simultaneously, filtering for those who respond positively before investing significant resources.

This approach inverts the traditional recruitment funnel. Instead of identifying a specific source and developing them over time, MSS officers cast a wide net and see who swims in. The yield rate is low—most approaches go nowhere—but the cost per approach is also low. The math favors volume.

Western services have been slower to adopt these methods, constrained by legal frameworks designed for a different era. Executive Order 12333, which governs US intelligence activities, was written when “collection” meant something specific and bounded. Its permissive negative framing—“not prohibited by law,” “may indicate involvement”—creates authorization through absence of explicit prohibition, but the absence is ambiguous. Can a CIA officer create a fake LinkedIn profile to approach a potential source? The order does not clearly prohibit it. Whether it permits it depends on interpretations that have not been publicly tested.

The legal ambiguity has created a policy gap that functions as a strategic choice. By not clearly authorizing social media exploitation, US intelligence leadership has effectively prohibited it at scale—not through explicit restriction but through the risk aversion that ambiguity breeds. Officers who might use these tools face career risk if something goes wrong and the authorization proves insufficient. The safe choice is not to try.

The Communications Paradox

Perhaps the most profound transformation has occurred in how case officers communicate with their sources. The Cold War toolkit—dead drops, brush passes, one-time pads—assumed that the primary threat was interception of the message itself. Encrypt the content, and the communication is secure.

The digital age has revealed this assumption as naive. The content of a communication matters less than its metadata: who communicated with whom, when, for how long, from what location. A source who exchanges encrypted messages with an unknown party every Tuesday at 3 PM has revealed something important even if the messages themselves are unreadable. The pattern is the product.

Intelligence services have responded by moving communications to platforms that promise both encryption and metadata protection. Signal, Telegram, and similar applications have become standard tools—but their adoption creates its own problems. Commercial encryption apps are designed for civilian use, which means they are designed for convenience rather than operational security. They leave traces on devices. They depend on infrastructure controlled by private companies. They can be compromised through endpoint attacks that bypass encryption entirely.

The deeper problem is that any regularized communication pattern creates a signature. A source who checks a covert communication channel every day at the same time has created a behavioral pattern that sophisticated surveillance can detect. The channel itself may be secure; the act of accessing it is not.

This has pushed some services toward what might be called “burst communication”—infrequent, irregular contact that minimizes the pattern while accepting the cost of reduced responsiveness. A source who can only be contacted once a month is less useful than one available daily, but also less likely to be detected. The trade-off between operational tempo and operational security has shifted decisively toward security.

The most sophisticated services have begun experimenting with AI-mediated communication, where machine learning systems manage the timing and routing of messages to obscure patterns. But this creates a new vulnerability: the AI system itself becomes a target. Compromise the system, and you compromise every communication it handles.

The Biometric Paradox

Facial recognition and other biometric systems have created an unexpected asymmetry in HUMINT operations. The technology works better on some populations than others—and the populations it works worst on have become, perversely, more valuable as sources.

Studies consistently show that facial recognition systems have false positive rates 10 to 100 times higher for Asian and African faces than for European faces. This is a failure of the technology, rooted in training data that overrepresents European faces. But from an operational perspective, it creates an opportunity. Populations historically excluded from biometric databases—and populations on whom biometric systems perform poorly—become more valuable precisely because they are harder to track.

This inverts traditional targeting logic. A source who can move through surveillance systems without being reliably identified is more operationally valuable than one who cannot, independent of their access to sensitive information. The biometric shadow becomes a form of natural cover.

The implications extend to officer selection and deployment. An intelligence service seeking to operate in an environment saturated with facial recognition has an incentive to deploy officers whose faces the systems cannot reliably match. This creates pressure toward demographic diversity in officer corps—not for reasons of equity, but for reasons of operational effectiveness.

The paradox deepens when one considers that the same biometric systems used for surveillance are also used for authentication. A source whose face cannot be reliably matched by surveillance systems also cannot be reliably authenticated by access control systems. The shadow that protects also excludes.

The Training Gap

The transformation of HUMINT tradecraft has outpaced the institutions responsible for teaching it. Training programs designed for the analog age struggle to prepare officers for digital operations, while programs designed for digital operations often neglect the interpersonal skills that remain the core of the discipline.

The fundamental tension is between two different skill sets. Traditional HUMINT requires the ability to build trust, read people, and navigate complex social situations—skills that are developed through practice and mentorship, not instruction. Digital HUMINT requires technical sophistication, operational security awareness, and comfort with tools that change faster than curricula can adapt. Few officers excel at both.

The institutional response has been to specialize. The CIA’s Directorate of Digital Innovation, created in 2015, houses technical capabilities that support HUMINT operations. The Directorate of Operations retains responsibility for the operations themselves. But the interface between directorates creates friction. Technical specialists who understand the digital environment may not understand the human dynamics of recruitment. Case officers who understand recruitment may not understand the technical vulnerabilities their operations create.

This specialization has a deeper cost. The guild model of knowledge transfer—where masters trained apprentices through years of close collaboration—has broken down. Digital tools promise to accelerate training by codifying tradecraft into procedures and checklists. But codified knowledge is not the same as embodied knowledge. A checklist can tell an officer what to do; it cannot teach judgment about when to deviate from the checklist.

The generational dimension compounds the problem. Officers trained before the digital transformation carry institutional knowledge that cannot be easily transmitted to digital natives who have never known a world without smartphones. Digital natives, in turn, have intuitions about online behavior that their predecessors lack. Neither generation fully understands the other’s operational reality.

The Adversary Adapts

Western intelligence services are not the only ones adapting to the digital age. Russian and Chinese services have proven at least as capable of exploiting digital tools—and in some cases more capable, unconstrained by the legal and ethical frameworks that bind Western operations.

Russian intelligence has demonstrated particular sophistication in using digital platforms for influence operations that blur the line between HUMINT and information warfare. The Internet Research Agency, exposed during the 2016 US election interference, represented a fusion of traditional agent-of-influence techniques with social media amplification. The “agents” were often unwitting—Americans who shared content without knowing its origin—but the operational logic was pure HUMINT: identify susceptible individuals, provide them with material that serves Russian interests, and let them do the distribution.

Chinese intelligence has taken a different approach, emphasizing scale over sophistication. The MSS reportedly maintains thousands of fake social media profiles used for initial contact with potential sources. Most approaches fail. But the cost of failure is negligible, and the occasional success yields access that would have been impossible through traditional methods.

Both adversaries have also invested heavily in counter-HUMINT capabilities enabled by digital surveillance. The Chinese social credit system, whatever its domestic purposes, functions as a continuous monitoring system for behavioral anomalies that might indicate contact with foreign intelligence. Russian services have demonstrated the ability to identify Western intelligence officers through pattern analysis of their digital exhaust—movements, communications, financial transactions—even when those officers believed they were operating securely.

The result is an intelligence environment where both offense and defense have been transformed, but not symmetrically. The advantage has shifted toward services willing to operate at scale, accept high failure rates, and aggregate data without legal constraint. Western services, bound by laws designed for a different era, find themselves playing defense on a field that favors offense.

What Comes Next

The trajectory is clear, even if the destination is not. HUMINT will not disappear—the need for human sources with access to adversary intentions remains as acute as ever. But the discipline will continue to transform in ways that challenge traditional assumptions.

Three developments seem likely. First, the integration of AI into HUMINT operations will accelerate. Machine learning systems will handle targeting, pattern analysis, and communication security, freeing human officers to focus on the irreducibly human elements of the discipline: building trust, assessing motivation, making the pitch. This integration will create new vulnerabilities even as it addresses old ones.

Second, the legal and policy frameworks governing digital HUMINT will eventually catch up to operational reality. The current ambiguity cannot persist indefinitely. Either Western services will receive clear authorization to exploit digital tools at scale, or they will be explicitly prohibited from doing so. The choice will shape the balance of intelligence power for a generation.

Third, the biometric surveillance mesh will continue to expand, eventually closing most of the shadows where HUMINT operations currently hide. When that happens, the discipline will face a choice: accept dramatically reduced operational tempo, or develop new methods of hiding in plain sight that have not yet been invented.

The spy who couldn’t disappear will need to become the spy who was never worth noticing. In a world where everyone is watched, the only cover is insignificance.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Can intelligence agencies still use traditional spy techniques like dead drops? A: Yes, but with significant modifications. Dead drops remain useful precisely because they avoid digital signatures, but the locations must now account for ubiquitous camera coverage. Services increasingly use “virtual dead drops”—cloud storage accounts, gaming platforms, or other digital spaces—that mimic the asynchronous, deniable nature of physical dead drops while avoiding the surveillance mesh blanketing urban environments.

Q: How do spies communicate securely in the digital age? A: The short answer is: with great difficulty. Commercial encrypted messaging apps like Signal provide content security but leave metadata traces. The most sensitive communications often revert to older methods—brief in-person meetings, one-time pads, or burst transmissions—that sacrifice convenience for security. No digital communication method is considered truly secure against a sophisticated nation-state adversary.

Q: Has social media made it easier or harder to recruit spies? A: Both. Social media dramatically simplifies the identification and initial assessment of potential sources—their access, vulnerabilities, and motivations are often publicly visible. But it also creates new risks: fake profiles can be detected, approaches can be monitored, and the digital record of any relationship creates evidence that can later be used for prosecution or blackmail. The net effect favors services willing to operate at scale and accept high failure rates.

Q: What is a “legend” in intelligence terminology? A: A legend is a false identity used by an intelligence officer operating undercover. In the digital age, a credible legend requires not just documents and a backstory, but a complete digital history: social media accounts, email records, location data, and financial transactions stretching back years. Creating and maintaining such legends has become one of the most resource-intensive aspects of modern HUMINT operations.