The Sacrificial Fleet

Australia's military exists to signal commitment through spectacular failure, not to win wars. This explains why $50 billion in annual spending hasn't produced readiness for high-intensity conflict.

The Sacrificial Fleet

Australia’s military exists to die for Taiwan. Not to win—to signal commitment through spectacular failure. This inversion of military logic explains why the Australian Defence Force, despite consuming $50 billion annually, remains structurally unprepared for high-intensity conflict within any timeframe that matters.

The question of Australia’s readiness for a Taiwan crisis assumes readiness means capability. It doesn’t. Australia’s force structure optimizes for symbolic sacrifice rather than operational effectiveness. Like ritual offerings in anthropological theory, the value comes from costliness—sacrificing something worthless signals nothing. Forces optimized for survival become worthless as commitment signals.

The Metabolic Reality

Ukraine consumes 10,000 drones monthly. Russia fires 20,000 artillery rounds daily while Ukraine manages 6,000. These numbers establish a metabolic floor for modern conflict—a minimum consumption rate below which forces become combat-ineffective regardless of platform sophistication.

Australia’s entire annual artillery production: zero rounds. The guided weapons plan commits $21 billion for sovereign missile manufacturing, with GMLRS production starting “by the end of 2025.” But GMLRS are precision weapons—expensive, complex, requiring months to manufacture. High-intensity conflict burns through basic ammunition at industrial rates.

The United States produced 240,000 artillery shells annually pre-Ukraine—barely 40 days of Ukrainian consumption. Australia produces none and lacks the industrial base to begin meaningful production within two years. The energetics bottleneck alone—explosives and propellants require specialized facilities with multi-year construction timelines—makes surge production impossible.

Consider the cascade: combat units consuming ammunition faster than peacetime production rates, logistics formations taking casualties while trying to resupply forward positions, reduced delivery throughput forcing combat units into less efficient operations that consume more fuel per mission. This metabolic cascade cannot be solved by buying better platforms.

The Conjuration Problem

Australia’s defence workforce faces 9% annual attrition—triple the US rate. Even when recruitment succeeds, the system hemorrhages trained personnel. This creates what researchers call “necromantic leakage”—the specialized knowledge required for modern military systems exists primarily in workers approaching retirement, yet the system cannot retain the knowledge it successfully transfers.

The submarine program exemplifies this impossibility. AUKUS requires delivery in the 2040s, but the workforce to build them needs four years apprenticeship (with 45% failure rates) plus 5-10 years experience. Starting from 2025, workers entering apprenticeships today will reach peak capability around 2035—assuming they don’t join the 9% who leave annually.

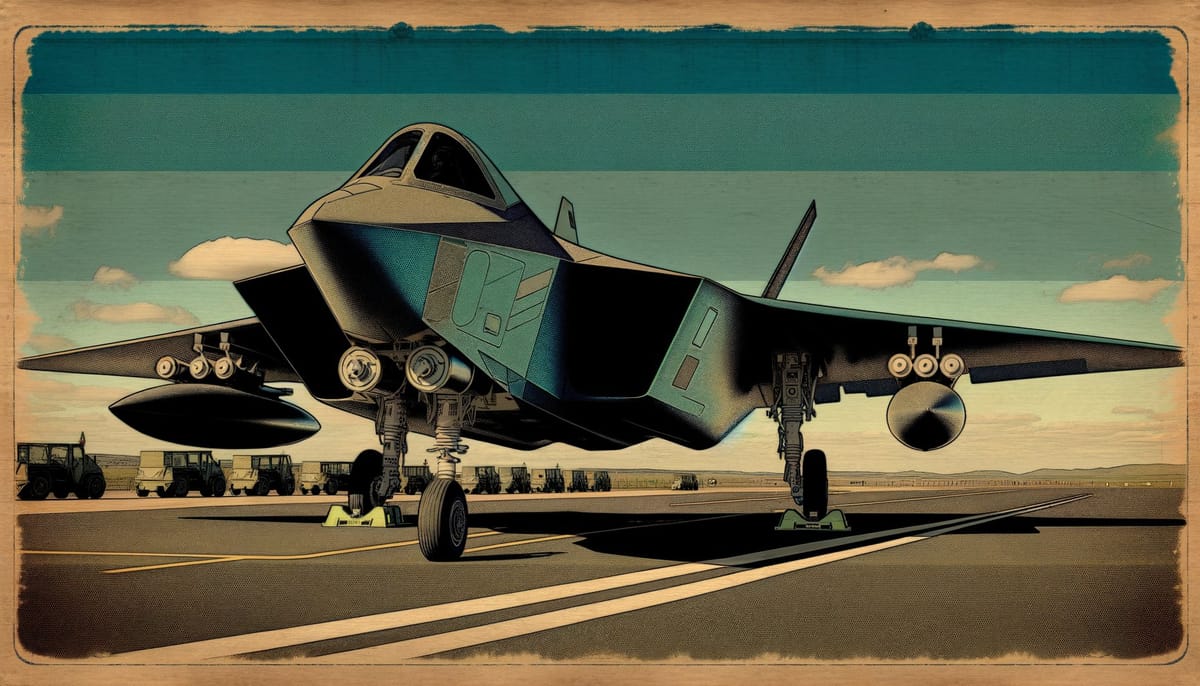

Software presents an even starker constraint. The F-35’s Block 4 upgrade has become a study in capability reduction—when software fails, the response is formally reducing promised capabilities while maintaining schedule milestones. The Pentagon links F-35 software instability directly to supply chain problems, revealing that non-functional code creates the same logistics void as missing physical parts.

The Dependency Trap

China processes 90% of rare earth elements despite producing only 60-70% of raw ore. This means Australian F-35 engines, requiring dysprosium and terbium for magnets, depend on Chinese processing even when the raw materials come from Australian mines. The dependency isn’t geological—it’s industrial.

Alternative sources exist in mine tailings, coal ash, and electronic waste. But new processing facilities require 5-7 years for environmental permitting alone, before construction begins. The constraint isn’t scarcity—it’s regulatory timelines designed for peacetime optimization.

Australia closed three refineries in ten years, eliminating local fuel production capacity. This establishes a hard metabolic ceiling on sustained operations. Without local refining, Australia cannot maintain the fuel throughput required for high-intensity operations regardless of stockpile size.

The Alliance Illusion

AUKUS assumes capability-sharing during crisis, but the USAF operates at 60% mission-capable rates during peacetime. If Australia expects to lease P-8s or other platforms during a Taiwan crisis, the donor is already operating below combat-ready thresholds. Alliance burden-sharing works when only one member faces crisis—it fails when all members surge simultaneously.

The production asymmetry compounds this problem. China produces 120+ J-20 stealth fighters annually while the US receives 48 F-35s. But US production must supply itself plus Australia, Japan, South Korea, and European partners from the same production line. Allied collective demand exceeds adversary single-source production during peacetime—the gap widens during conflict.

What Can Actually Be Built

Within two years, Australia can realistically deploy:

Immediate capabilities (3-6 months): Software upgrades to existing F-35s, accelerated munitions purchases from US stocks, expanded fuel storage at northern bases, enhanced cyber defenses using commercial technologies.

Near-term additions (6-18 months): First GMLRS production runs, upgraded air defense systems for critical infrastructure, expanded Pine Gap and signals intelligence capabilities, additional C-130J aircraft from existing orders.

Stretched timelines (18-24 months): Enhanced submarine maintenance facilities, expanded ammunition storage, improved port infrastructure for US logistics, basic drone manufacturing using commercial components.

What cannot be built: Industrial-scale ammunition production, sovereign fuel refining, advanced shipbuilding capacity, rare earth processing, or the skilled workforce to operate any of these systems at scale.

The Commitment Signal

Australia’s strategic purpose isn’t military effectiveness—it’s credible commitment signaling. Small allies demonstrate resolve by accepting costs that larger allies could avoid. Australian forces in a Taiwan scenario function as tripwires, generating audience costs that lock both Australia and the US into escalation.

But this logic requires the sacrifice to be visible and costly. Stealth platforms optimized for survival make poor commitment signals—adversaries cannot see them die. The optimal commitment force would be expensive, vulnerable, and operationally significant enough that losing it would hurt. Australia’s current force structure accidentally achieves this: platforms too sophisticated to risk, too few to matter operationally, too expensive to lose without political consequences.

The Moral Injury Factor

Australian military culture centers on defending home territory—Kokoda, Darwin, the ANZAC tradition. Deploying to Taiwan for distant alliance obligations violates this implicit contract. Moral injury occurs when personnel are forced to take actions that violate core moral beliefs, and research shows this can occur before deployment through anticipation of morally questionable orders.

The psychological readiness problem isn’t training—it’s meaning-making. Personnel understand defending Australia but struggle with dying for Taiwan. This existential crisis compounds operational problems: forces that question mission legitimacy perform poorly regardless of equipment quality.

The Path Forward

Australia faces three realistic options within a two-year window:

Option A: Honest Incapability. Acknowledge that Australia cannot meaningfully contribute to Taiwan’s defense and focus on homeland security. This preserves forces for scenarios Australia can actually influence while avoiding symbolic commitments that exceed capability. Political feasibility: Low. Abandons alliance credibility for operational honesty.

Option B: Optimized Sacrifice. Restructure forces explicitly for commitment signaling rather than operational effectiveness. Deploy visible, expensive assets in forward positions where their loss would be strategically meaningful. Accept that the purpose is political, not military. Political feasibility: Medium. Aligns resources with actual strategic purpose.

Option C: Industrial Mobilization. Emergency legislation to override environmental regulations, conscript skilled workers, and nationalize critical production. Begin immediate construction of ammunition plants, fuel refineries, and rare earth processing. Political feasibility: Low. Requires wartime powers during peacetime.

Australia will likely choose none of these, instead maintaining the current trajectory: expensive platforms without ammunition, alliance commitments without capability, and strategic signaling without strategic clarity.

The most probable scenario is muddled escalation—Australian forces committed to Taiwan scenarios they cannot meaningfully influence, generating political costs without military benefits. The ADF will perform its actual function: demonstrating Australian resolve through spectacular, expensive failure.

FAQ: Key Questions Answered

Q: Could Australia’s military actually help defend Taiwan? A: Not meaningfully within two years. Australia lacks the ammunition stockpiles, fuel production, and industrial base for sustained high-intensity operations. The ADF could provide symbolic support and limited capabilities like intelligence and logistics, but cannot alter the military balance.

Q: What military equipment can Australia realistically build by 2027? A: Basic munitions like GMLRS missiles starting in 2026, software upgrades to existing platforms, and commercial-technology adaptations like drones. Major platforms (ships, aircraft, advanced missiles) require 5-10 year development cycles that cannot be compressed.

Q: How does Australia’s defense spending compare to actual readiness? A: Australia spends $50 billion annually but optimizes for platform acquisition rather than operational sustainability. The budget buys sophisticated weapons without the ammunition, fuel, or industrial base to sustain their use in conflict.

Q: What would Australia’s role be in a Taiwan crisis? A: Primarily symbolic—demonstrating alliance commitment through visible deployment of expensive assets. Operationally, Australia might provide intelligence, logistics support, and air defense for US bases, but cannot significantly influence the military outcome.

The Quiet Surrender

The Australian Defence Force will not be ready for a Taiwan crisis within two years because readiness was never the objective. The force structure optimizes for alliance signaling, not warfighting capability. This represents a quiet surrender of strategic autonomy disguised as alliance solidarity.

The tragedy is not that Australia lacks military capability—it’s that Australian strategic culture cannot admit what the force structure reveals. The ADF exists to demonstrate commitment through sacrifice, not to achieve military objectives through victory. Understanding this inversion explains why decades of increased defense spending have not produced increased defense capability.

Australia has built a military designed to lose beautifully. Whether this serves Australian interests depends on whether beautiful failure is worth $50 billion annually.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- Australia’s Defence Strategic Review 2023 - strategic framework and force development timelines

- Australian Guided Weapons and Explosive Ordnance Plan - sovereign manufacturing capabilities and constraints

- Pentagon Report on F-35 Supply Chain Issues - software stability and logistics vulnerabilities

- China’s Rare Earth Supply Chain Dominance - critical material dependencies

- Australian Defence Personnel Shortages - workforce and retention challenges

- Understanding Moral Injury Among Veterans - psychological readiness factors