The Quiet Realignment: How Australia and Indonesia Are Rewriting Indo-Pacific Security

The new Australia-Indonesia defense treaty creates strategic ambiguity that complicates adversary planning while preserving Indonesian non-alignment—a model that could reshape regional security cooperation beyond traditional alliance structures.

The Quiet Realignment

Indonesia never does anything quietly. The archipelago’s 17,000 islands sprawl across three time zones, its 280 million people speak 700 languages, and its politics unfold through carefully orchestrated spectacle. So when President Prabowo Subianto and Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese announced their “watershed” defense treaty on November 12, 2025, the muted response revealed more than the fanfare would have.

The Australia-Indonesia Treaty on Common Security represents the deepest military partnership between the two nations since independence. Yet neither Beijing nor Washington issued sharp statements. ASEAN barely acknowledged it. Regional analysts called it “significant but not transformative.” This studied indifference masks a more profound shift: middle powers are quietly building their own security architecture while great powers focus elsewhere.

The treaty matters precisely because it doesn’t threaten anyone directly. Instead, it creates new facts on the ground that will reshape Indo-Pacific security through accumulation rather than confrontation.

The Architecture of Hedging

Indonesia’s foreign policy operates on a simple principle: never choose sides until you absolutely must. The “free and active” doctrine, enshrined since the 1950s, has allowed Jakarta to extract benefits from all major powers while committing fully to none. The new treaty with Australia appears to violate this logic. It doesn’t.

The agreement builds on the August 2024 Defence Cooperation Agreement, which already established frameworks for joint exercises, technology transfer, and maritime security cooperation. What the 2025 treaty adds is a consultation mechanism: both countries commit to “consult at leader and ministerial level” when either perceives a security threat, then consider whether to respond “individually or jointly.”

This language sounds anodyne. It isn’t. The consultation clause creates an expectation of coordination without the burden of alliance obligations. Unlike NATO’s Article 5 or the ANZUS Treaty’s Article IV, the Australia-Indonesia pact requires only that leaders talk, not that they act. This gives Indonesia maximum flexibility while signaling to potential adversaries that Australian and Indonesian responses might be coordinated.

The mechanism reflects Prabowo’s particular approach to statecraft. The former special forces commander understands that strength comes from unpredictability as much as capability. By creating ambiguity about how Australia and Indonesia might respond to various scenarios, the treaty complicates adversary planning without constraining Indonesian options.

For Australia, the treaty solves a different problem. Canberra has spent decades trying to integrate Indonesia into Western security frameworks, with limited success. The new approach reverses the logic: instead of pulling Indonesia toward existing alliances, Australia creates a parallel structure that accommodates Indonesian strategic culture while advancing Australian interests.

The Geography of Power

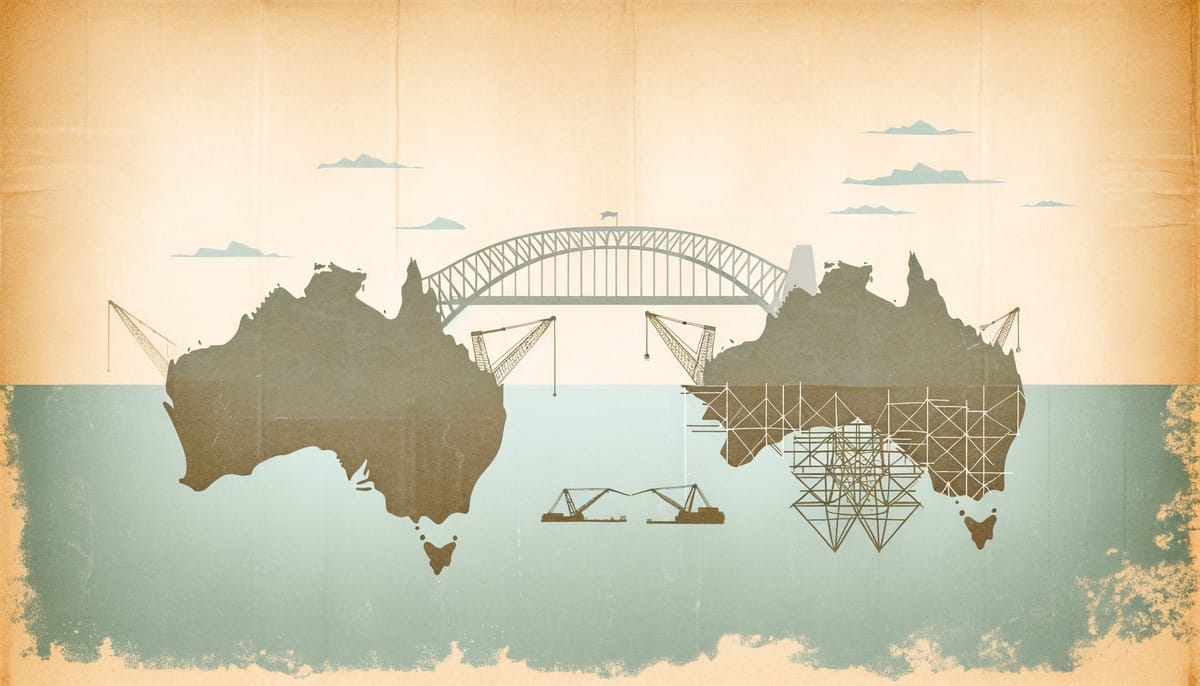

Maritime Southeast Asia’s strategic importance has always exceeded its military power. The region contains four of the world’s nine critical maritime chokepoints, including the Strait of Malacca, through which 25% of global trade passes. Indonesia controls three of these straits and sits astride the sea lanes connecting the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

This geography creates asymmetric leverage. Indonesia cannot project power globally, but it can complicate anyone else’s ability to do so. The archipelago’s position means that major powers must either cooperate with Jakarta or work around it—and working around Indonesia is expensive, time-consuming, and ultimately unsustainable.

The Australia-Indonesia treaty recognizes this reality. Rather than trying to integrate Indonesian forces into Western command structures, the agreement focuses on maritime domain awareness, intelligence sharing, and coordinated responses to specific threats. This allows both countries to leverage their geographic advantages while avoiding the political complications of formal alliance membership.

Joint exercises like Keris Woomera, conducted under the 2024 agreement, demonstrate the practical benefits. Australian and Indonesian forces practiced coordinated responses to scenarios including terrorism, piracy, and humanitarian disasters. These exercises build interoperability without requiring doctrinal alignment—Indonesian forces can work with Australian units without adopting Australian strategic priorities.

The maritime focus also serves broader regional interests. Both countries face similar challenges from illegal fishing, people smuggling, and maritime terrorism. By coordinating responses to these sub-strategic threats, Australia and Indonesia build habits of cooperation that could extend to larger challenges if circumstances require.

The Limits of Alignment

Indonesia’s commitment to non-alignment remains absolute, and the treaty carefully respects this constraint. The consultation mechanism specifically avoids language about “common threats” or “shared values”—formulations that might imply ideological alignment. Instead, it focuses on procedural cooperation: how to coordinate, not what to coordinate against.

This reflects deeper structural realities. Indonesia’s economy depends heavily on Chinese trade and investment, while its security relationships increasingly involve the United States and Australia. Jakarta cannot afford to alienate either side completely, so it maintains relationships with both while committing fully to neither.

The treaty acknowledges these constraints by creating what defense analysts call “compartmentalized cooperation.” Military-to-military relationships operate separately from broader diplomatic alignment. Indonesian and Australian forces can train together, share intelligence on specific threats, and coordinate responses to regional challenges without Jakarta endorsing Canberra’s broader strategic priorities.

This compartmentalization serves both countries’ interests. Australia gains access to Indonesian intelligence networks and basing rights for humanitarian operations without requiring Indonesia to support controversial policies like AUKUS or Quad initiatives. Indonesia receives advanced training, equipment, and intelligence capabilities without compromising its non-aligned status.

The arrangement also creates strategic ambiguity that benefits both parties. Potential adversaries cannot assume Indonesian neutrality in all scenarios, but they also cannot assume automatic Indonesian opposition. This uncertainty complicates planning and may deter aggressive actions that might otherwise seem low-risk.

The ASEAN Calculation

The treaty’s relationship with ASEAN mechanisms reveals the organization’s evolving role in regional security. Officially, both Australia and Indonesia emphasized that the bilateral agreement “complements and reinforces” ASEAN-led frameworks like the ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting Plus (ADMM-Plus). The reality is more complex.

ASEAN’s consensus requirement makes it effective at preventing conflict but ineffective at responding to specific threats. The organization can facilitate dialogue and build confidence, but it cannot coordinate rapid responses or share sensitive intelligence. Bilateral arrangements like the Australia-Indonesia treaty fill these gaps by operating outside ASEAN’s consensus constraints.

This creates a two-track system: ASEAN handles broad diplomatic coordination and confidence-building, while bilateral partnerships manage operational cooperation. The arrangement preserves ASEAN’s face while acknowledging its limitations. Indonesia can maintain its commitment to “ASEAN centrality” while building practical security relationships that ASEAN cannot provide.

The model may spread. Malaysia and Singapore already have similar arrangements with Australia, and Thailand has expressed interest in upgrading its defense cooperation agreements. Rather than replacing ASEAN, these bilateral partnerships could create a network of overlapping relationships that provides both flexibility and redundancy.

This evolution reflects changing threat patterns. Traditional interstate conflicts remain possible, but the region’s most pressing security challenges—terrorism, cyber attacks, maritime crime, and climate-related disasters—require rapid, coordinated responses that ASEAN’s consensus mechanisms cannot provide. Bilateral partnerships offer the speed and specificity that multilateral frameworks lack.

The Great Power Response

China’s muted response to the treaty reflects careful calculation rather than indifference. Beijing recognizes that the agreement strengthens Australian influence in Southeast Asia but avoids the provocative elements that might justify a sharp response. The treaty contains no explicit references to Chinese threats, includes no new military bases, and commits Indonesia to nothing beyond consultation.

This restraint serves Chinese interests by avoiding actions that might push Indonesia closer to Western security frameworks. A harsh Chinese response might convince Jakarta that Beijing poses a direct threat, potentially justifying closer military cooperation with Australia. By treating the treaty as routine diplomacy, China maintains its position that regional security arrangements should remain inclusive rather than exclusive.

The United States faces a more complex calculation. The treaty advances American interests by strengthening Australian capabilities and building Indonesian ties to Western security networks. But it also demonstrates that key allies are building security relationships that operate independently of American leadership. This could strengthen overall deterrence or it could fragment Western responses to Chinese challenges.

Washington’s response has been carefully supportive but not enthusiastic. Officials praised the agreement while emphasizing America’s continued central role in regional security. This suggests recognition that middle-power partnerships serve American interests even when they operate outside American frameworks.

The Japanese response reveals different concerns. Tokyo has invested heavily in building its own relationships with Southeast Asian nations and may worry that the Australia-Indonesia partnership could complicate Japanese initiatives. However, Japan’s focus on economic cooperation rather than security partnerships means the overlap is limited.

The Operational Reality

The treaty’s practical impact will depend on implementation rather than rhetoric. The 2024 Defence Cooperation Agreement provides the legal framework, but translating legal authorities into operational capabilities requires sustained effort across multiple bureaucracies.

Early indicators suggest serious commitment from both sides. The November 2024 Keris Woomera exercise involved 2,000 personnel from both countries—the largest bilateral military exercise in the relationship’s history. Australian forces gained experience operating in Indonesian terrain and conditions, while Indonesian units trained with advanced Australian equipment and techniques.

Intelligence sharing represents another early success. Both countries face threats from regional terrorist networks, and their intelligence services have developed productive cooperation on specific investigations. The treaty formalizes these relationships and extends them to broader security challenges including cyber threats and foreign interference.

Technology transfer provisions could prove most significant over time. The agreement allows for “exchange or transfer of technology, technical assistance, training, provision of defence equipment and joint production.” This creates possibilities for Indonesian defense industries to access Australian technologies while giving Australian companies access to Indonesian manufacturing capabilities and regional markets.

However, implementation faces significant obstacles. Different procurement systems, classification standards, and operational procedures create friction that formal agreements cannot eliminate. Building genuine interoperability requires years of sustained cooperation at working levels—cooperation that must survive political changes in both countries.

The Regional Ripple Effects

Other Southeast Asian nations are watching the Australia-Indonesia partnership with interest and concern. Malaysia and Thailand have expressed interest in similar arrangements, while Singapore already maintains close defense ties with Australia through the Five Power Defence Arrangements and bilateral agreements.

This could create a network of overlapping partnerships that strengthens regional security cooperation. Alternatively, it could fragment ASEAN unity by creating different tiers of security relationships. Much depends on how Indonesia manages its role as ASEAN’s largest member while pursuing bilateral partnerships that operate outside ASEAN frameworks.

India represents another interested observer. New Delhi has invested heavily in building relationships with Southeast Asian nations as part of its “Act East” policy. The Australia-Indonesia treaty demonstrates that middle powers can build significant security partnerships without great power sponsorship—a model that could serve Indian interests in other regions.

The treaty also affects regional arms markets and defense industrial cooperation. Australian companies gain access to Indonesian markets and manufacturing capabilities, while Indonesian firms can access Australian technologies and training. This could accelerate regional defense industrial development and reduce dependence on external suppliers.

The Enduring Questions

Three critical uncertainties will determine the treaty’s long-term significance. First, how will it survive leadership changes in both countries? The agreement reflects personal relationships between current leaders, but institutional relationships must outlast individual tenures.

Second, how will the consultation mechanism work in practice? The treaty requires leaders to consult when either country perceives threats, but it provides no definition of what constitutes a threat worthy of consultation. This ambiguity is intentional but could create friction if one side seeks consultation that the other considers unnecessary or inappropriate.

Third, how will the partnership evolve if regional tensions escalate? The treaty was negotiated during a period of relative stability, but its real test will come during crises. Whether the consultation mechanism produces coordinated responses or reveals fundamental disagreements will determine the agreement’s strategic value.

The treaty’s success will ultimately depend on whether both countries can maintain the delicate balance between cooperation and independence that makes the partnership attractive to Indonesia while providing genuine benefits to Australia. This requires sustained attention from leaders who understand that middle-power partnerships succeed through patience rather than pressure.

FAQ: Understanding the Treaty’s Impact

Q: Does this treaty mean Indonesia is abandoning its non-aligned foreign policy? A: No. The treaty carefully preserves Indonesian strategic autonomy by requiring only consultation, not coordinated action. Indonesia can maintain relationships with all major powers while building specific cooperation with Australia on shared security challenges.

Q: How does this affect Australia’s AUKUS commitments and relationship with the United States? A: The treaty complements rather than competes with AUKUS. Australia gains additional regional partnerships that could support broader deterrence efforts, while the focus on maritime security aligns with AUKUS objectives in the Indo-Pacific.

Q: What specific military capabilities will Australia and Indonesia develop together? A: The treaty enables joint training, intelligence sharing, and technology transfer focused on maritime security, counter-terrorism, and humanitarian response. It does not establish joint military units or shared command structures.

Q: Could this treaty model spread to other Southeast Asian countries? A: Possibly. Malaysia and Thailand have expressed interest in similar arrangements. The model’s success in preserving national autonomy while enabling practical cooperation could make it attractive to other middle powers seeking security partnerships without alliance obligations.

The Quiet Revolution

The Australia-Indonesia treaty represents something new in regional security: a partnership designed for an era when middle powers cannot rely entirely on great power protection but also cannot afford great power competition. By creating mechanisms for cooperation without requiring alignment, the treaty offers a model for how regional states might navigate an increasingly complex strategic environment.

The agreement’s significance lies not in what it changes immediately, but in what it makes possible over time. Each successful cooperation builds trust and capability for more ambitious partnerships. Each crisis managed jointly demonstrates the value of coordination without subordination.

Whether this model spreads will depend on its practical success and the broader trajectory of great power competition. If the Australia-Indonesia partnership demonstrates that middle powers can enhance their security through careful cooperation, other regional states may follow. If great power tensions escalate beyond current levels, the pressure to choose sides may overwhelm the appeal of strategic autonomy.

For now, the treaty represents a quiet bet that the future belongs to those who can cooperate without surrendering independence. In a region defined by diversity and shaped by geography, that may prove to be the most realistic path to lasting security.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- Australia-Indonesia Defence Cooperation Agreement - official announcement and key provisions

- Treaty text and parliamentary analysis - legal framework and implementation details

- Al Jazeera coverage of the 2025 treaty - regional perspectives and consultation mechanisms

- The Diplomat analysis - strategic implications and non-alignment considerations

- ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting Plus framework - multilateral security architecture context

- Australian Department of Foreign Affairs Indo-Pacific assessment - great power competition dynamics