The Purge Paradox: Xi's Anti-Corruption Campaign Is Crippling the Military It Was Meant to Strengthen

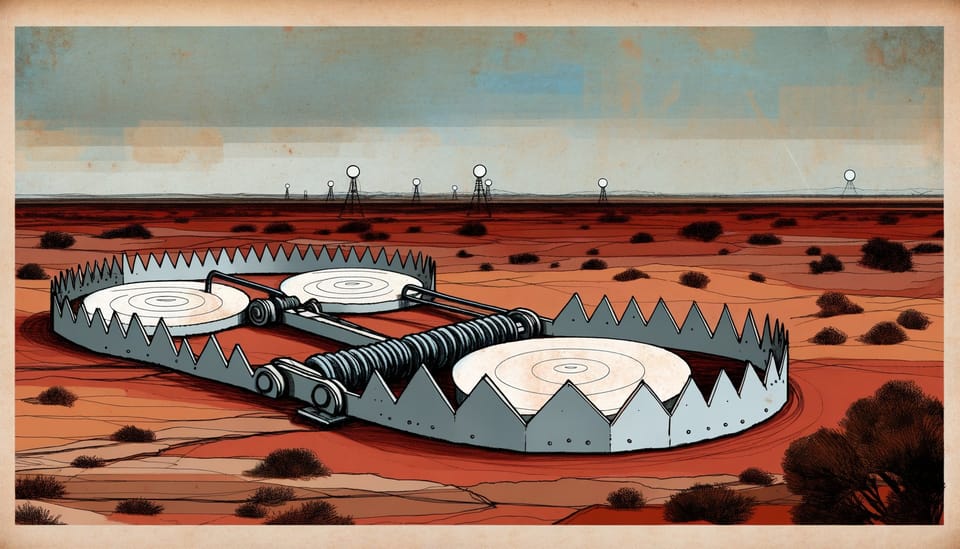

China's military purges have removed at least fifteen senior officers and cut the Central Military Commission nearly in half. The campaign reveals not strength through discipline but a loyalty-competence trap that may leave the PLA weaker precisely when Xi needs it strongest.

The Purge Paradox

Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign has consumed his own military. Since 2023, at least fifteen senior officers and defense executives have been removed from their posts, including the commander of the Rocket Force—the service responsible for China’s nuclear arsenal. In October 2024, nine of the PLA’s most senior generals were expelled from the Communist Party, among them Central Military Commission Vice Chairman He Weidong and Admiral Miao Hua, the head of the Political Work Department. The Central Military Commission has been cut nearly in half.

The conventional reading treats this as a sign of strength: Xi rooting out corruption to build a more capable fighting force. The Pentagon’s 2024 report on Chinese military power echoes this ambivalence, noting that purges “may have disrupted” progress toward 2027 modernization goals while simultaneously acknowledging steady capability improvements. But this framing misses what the purges actually reveal. They are not a cure for institutional disease. They are a symptom of it—and the treatment may be worse than the illness.

The Corruption That Couldn’t Be Hidden

Start with what triggered the crackdown. Western analysts have long suspected that China’s Rocket Force suffered from procurement fraud, but the scale became impossible to ignore. Reports emerged of missile silos filled with water instead of fuel, of solid-propellant missiles that had degraded beyond use, of equipment contracts awarded to firms whose primary qualification was their connections to senior officers. The 2024 Pentagon report states bluntly that corruption “may have disrupted the PLA’s progress toward stated 2027 modernization goals.”

The numbers confirm the damage. According to SIPRI’s December 2024 analysis, Chinese defense firms saw revenues drop 10% in 2024 while the global defense industry grew 5.9%. Norinco, one of China’s largest arms manufacturers, suffered a 31% revenue decline. The cause, per SIPRI: “A host of corruption allegations in Chinese arms procurement led to major arms contracts being postponed or cancelled.” This is not trimming fat. This is industrial paralysis.

The pattern suggests something deeper than individual malfeasance. China’s defense procurement operated for decades on guanxi—relationship networks where personal connections determined contract awards, payment terms, and specification flexibility. This was not a bug in the system. It was the system. Private firms tolerated long payment cycles and shifting requirements because personal relationships with PLA officers guaranteed eventual payment and future contracts. Remove those relationships, and the entire informal architecture of defense production collapses.

The Equipment Development Department, which oversees weapons procurement, has been particularly devastated. Over half of the roughly fifteen senior officers purged between April 2023 and July 2024 came from this single organization. The department’s former head, General Li Shangfu, served as Defense Minister for seven months before disappearing from public view and being formally removed. His predecessor, General Wei Fenghe, has also been expelled from the Party.

What emerges is not a picture of surgical corruption removal but of institutional decapitation. The officers who understood how to navigate China’s opaque procurement system—how to balance political demands with technical requirements, how to maintain relationships with suppliers while meeting capability deadlines—are precisely the ones being eliminated.

The Loyalty-Competence Trap

Xi faces a problem that no amount of political will can solve: he cannot simultaneously maximize loyalty and competence. The officers most skilled at military modernization are those who rose through a system that rewarded relationship-building and creative interpretation of rules. The officers most loyal to Xi personally are those who avoided such entanglements—which often means they avoided the most complex and important programs.

The mathematics compound. When promotion criteria emphasize ideology “especially in upper echelons” while demanding technical competence, the PLA officer corps faces what machine-learning researchers would recognize as a label-noise problem. The ground truth—actual combat readiness—becomes increasingly decoupled from the measured signal—political reliability scores. Officers optimize for what gets measured. Measured loyalty replaces unmeasured capability.

This creates a cascade. Senior officers who survived the purges now face a choice: demonstrate initiative and risk being accused of corruption, or demonstrate caution and guarantee mediocrity. The rational response is what Chinese social media calls tang ping—lying flat. Do the minimum. Avoid exposure. Let someone else take the risk.

The new PLA discipline regulations issued in 2026 make this calculus explicit. They prioritize “strict political discipline” and target “erroneous political remarks.” Officers can now be punished not just for corruption but for saying the wrong thing about strategy, doctrine, or capability. In an organization preparing for potential conflict, this is a recipe for information suppression. Bad news stops flowing upward. Capability gaps go unreported. By 2027, senior leadership may have a completely distorted picture of what the PLA can actually do.

High-reliability organizations—nuclear power plants, aircraft carriers, surgical teams—depend on psychological safety in error reporting. Personnel must feel free to flag problems without fear of punishment. The PLA’s panoptic inspection regime creates the opposite: systematic concealment. Near-misses go unreported. Workarounds become normalized. The organization optimizes for appearance rather than performance.

The Industrial Hemorrhage

The purges have not merely disrupted procurement; they have severed the tacit-knowledge networks that made complex weapons development possible. Missile programs, in particular, depend on institutional memory that cannot be written down—fuel-handling protocols developed through decades of trial and error, supplier relationships built over careers, engineering workarounds that exist only in the minds of veteran technicians.

When senior officers are purged, their entire mentorship chains are contaminated. Protégés become suspect. Colleagues distance themselves. The informal networks that transmitted institutional knowledge—how to actually get things done within the bureaucracy—dissolve. What remains is the formal hierarchy, which in any military is necessary but not sufficient for actual operations.

The revenue collapse at Chinese defense firms reflects this rupture. The 31% decline at Norinco may represent not just cancelled contracts but the dismantling of revenue-generating side businesses that previously cross-subsidized research and development. If defense state-owned enterprises historically used export revenues and commercial ventures to fund off-book military R&D, the purges may have destroyed financing mechanisms that don’t appear in any official budget.

Western observers sometimes assume that China’s command economy can simply redirect resources to compensate. This misunderstands how innovation actually works. The Soviet Union could build nuclear weapons through brute-force resource allocation. It could not build competitive consumer electronics. Complex modern weapons systems require the kind of iterative problem-solving that depends on trust, experimentation, and tolerance for failure—precisely what anti-corruption campaigns destroy.

What the Silo Lids Reveal

Satellite imagery has documented a curious phenomenon at Chinese missile installations: silo lids that failed to close properly during construction, revealing the status of the facilities beneath. Western analysts treated this as an intelligence windfall. But the failures reveal something more significant than construction progress. They reveal quality-control breakdown.

The silo-lid glitch functions as what art theorists call an “a-subjective, unintentional, accidental glitch”—a failure that reveals accumulated technical debt and maintenance problems in ways that intentional disclosure never would. Unlike transparency theater, where states reveal capabilities they want adversaries to see, construction failures expose capabilities they wanted to hide. The pattern suggests that corruption in the Rocket Force extended beyond procurement into basic engineering competence.

This has implications for deterrence. China’s nuclear modernization depends on adversaries believing that its missiles will work as advertised. Every visible quality-control failure erodes that belief. The purges were supposed to restore confidence in the force. Instead, they have drawn attention to exactly how compromised the force may have been.

External observers now face a dilemma. Should they assume that the purges fixed the problems and that China’s nuclear forces are more capable than before? Or should they assume that the purges revealed the tip of an iceberg and that actual capabilities are worse than previously estimated? The honest answer is that no one knows—including, quite possibly, Xi Jinping himself.

The 2027 Question

China’s military modernization operates on a structured timeline: 2027 for “basic modernization” and ability to win regional wars, 2035 for full modernization, 2049 for “world-class” status. The 2027 goal is explicitly oriented toward Taiwan—building capabilities for coercion and potential warfighting against the United States and its allies.

The purges have created a temporal paradox. The officers being removed are precisely those whose careers spanned the doctrinal transition from “People’s War Under Modern Conditions” to “Informatized Local Wars.” They understood both the old system and the new requirements. Their replacements lack this institutional memory. The PLA must achieve 2027 goals without officers who organically evolved through the transformation that made those goals possible.

Japanese defense planners have noticed. Japan’s accelerated rearmament explicitly targets the 2027 milestone—not as a PLA capability peak but as a purge-induced brittleness window. The anti-corruption crackdown creates what one analyst called “headless bushido drones”: units with material readiness but severed command chains. If conflict came tomorrow, the PLA would field equipment without the experienced leadership to employ it effectively.

Russia has noticed too. Moscow is evaluating whether China can execute complex joint operations for a Taiwan contingency. The purges reveal not strength through discipline but structural brittleness—exactly the kind of vulnerability that makes alliance partners nervous. Putin has his own problems with military competence, as Ukraine demonstrated. He does not need a partner with the same disease.

The Resilience Question

Not everything points toward collapse. The PLA has institutional buffers that may absorb the shock. The 2016 reforms created theater commands designed to operate with significant autonomy. The professionalization of the non-commissioned officer corps—explicitly framed as the military’s “backbone”—provides a parallel authority structure that operates independently of officer succession chains. When purges remove senior officers, institutional investment in NCO professionalization may maintain operational continuity at the tactical level.

The PLA has also maintained operational tempo despite leadership chaos. Exercise frequency has not declined. Training continues. Equipment deliveries, while disrupted, have not stopped entirely. The organization is stressed but not paralyzed.

Moreover, Xi may calculate that short-term capability loss is acceptable if it produces long-term loyalty. A military that fears its leader more than it fears the enemy is not optimal for warfighting, but it is optimal for regime survival. Xi watched the Soviet Union collapse when the military declined to save the Party. He has no intention of repeating that mistake.

The question is whether Xi can have both: a military loyal enough to never threaten the Party and capable enough to threaten Taiwan. Historical evidence suggests this is difficult. Armies optimized for political control tend to underperform against external enemies. The Iraqi Republican Guard was loyal to Saddam Hussein. It was not effective against American forces.

The Trajectory

Where does this lead? Three scenarios bracket the range.

In the optimistic case, the purges are a one-time correction. Xi removes the most egregious offenders, installs loyal replacements, and allows the system to stabilize. New officers learn their jobs. Procurement resumes. The 2027 timeline slips by a year or two but remains achievable. China emerges with a military that is both more loyal and eventually more capable.

In the pessimistic case, the purges become self-sustaining. Each round of removals creates new suspects—the protégés and associates of those already purged. Paranoia spreads. Risk-aversion becomes endemic. The PLA’s formal capabilities continue to improve (ships get built, missiles get deployed) but its ability to actually fight degrades. By 2027, China fields a military that looks formidable on paper but cannot execute complex operations under fire.

In the most dangerous case, Xi recognizes the capability degradation and concludes that the window for action is closing. If the PLA is more capable today than it will be after years of loyalty-filtering, the rational choice is to act sooner rather than later. The purges, intended to strengthen China’s position, instead accelerate the timeline for confrontation.

The evidence supports the middle scenario as most likely. The PLA will continue to modernize. Ships will be launched. Aircraft will be delivered. But the human capital that translates equipment into capability is being systematically degraded. China will field a military that is simultaneously more advanced and less effective than it would have been without the purges.

This is the paradox Xi cannot escape. He needs a loyal military to survive. He needs a competent military to prevail. The two requirements are in tension, and every purge makes the tension worse.

FAQ: Key Questions Answered

Q: Has China actually delayed its 2027 military modernization goals? A: The Pentagon’s 2024 report states corruption “may have disrupted” progress toward 2027 goals but stops short of confirming delays. Revenue collapses at major defense firms (10% industry-wide, 31% at Norinco) suggest significant procurement disruption, though the full impact on capability timelines remains unclear.

Q: How many senior PLA officers have been purged since 2023? A: At least fifteen high-ranking officers and defense executives were removed between July and December 2023 alone. In October 2024, nine additional senior generals were expelled from the Communist Party, including CMC Vice Chairman He Weidong. The total continues to grow.

Q: Does the anti-corruption campaign make the PLA stronger or weaker? A: Both, in different dimensions. It removes officers engaged in procurement fraud, potentially improving equipment quality long-term. But it also destroys institutional knowledge networks, creates risk-aversion in remaining officers, and disrupts the informal systems that made defense production function. Net effect on warfighting capability is likely negative in the medium term.

Q: What does this mean for Taiwan? A: Uncertainty increases in both directions. The PLA may be less capable than previously assessed, reducing invasion risk. But if Xi believes capability is degrading, he may feel pressure to act before the window closes. Taiwan’s defense planners must prepare for both a weaker and a more desperate adversary.

The Mirror’s Edge

Xi Jinping’s father spent sixteen years in prison, purged by the very revolution he helped create. The young Xi was labeled a “reactionary student” and sent to the countryside for seven years of manual labor. He learned that the Party could destroy anyone—and that the only protection was to become the one doing the destroying.

The purges now consuming the PLA are not a departure from this logic but its culmination. Xi is building a military that cannot threaten him. Whether it can threaten anyone else is, for him, a secondary consideration. The corruption was real. The cure may be fatal. And the patient has no choice but to take the medicine.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- Pentagon 2024 China Military Power Report - Primary U.S. government assessment of PLA modernization and corruption impacts

- SIPRI Top 100 Arms Producers Analysis - Data on Chinese defense industry revenue collapse

- CNA Analysis of Military Purges - Assessment of purge impacts on PLA readiness

- South China Morning Post on New PLA Discipline Rules - Coverage of 2026 regulations prioritizing political discipline

- War on the Rocks Analysis of Rocket Force Corruption - Deep dive on why missile programs were particularly vulnerable

- Foundation for Defense of Democracies on Deterrence - Analysis of how purges affect cross-strait deterrence calculations

- New York Times on Xi’s Nuclear Force Concerns - Reporting on leadership anxiety about nuclear force reliability