The Philippines Cannot Defend What It Cannot Connect

China has developed specialized equipment to sever undersea cables at 4,000-meter depths. The Philippines routes 95% of its international data—including military command systems—through exactly such cables. If Beijing cuts these connections during a Taiwan crisis, Manila's ability to coordinate...

The Archipelago’s Achilles Heel

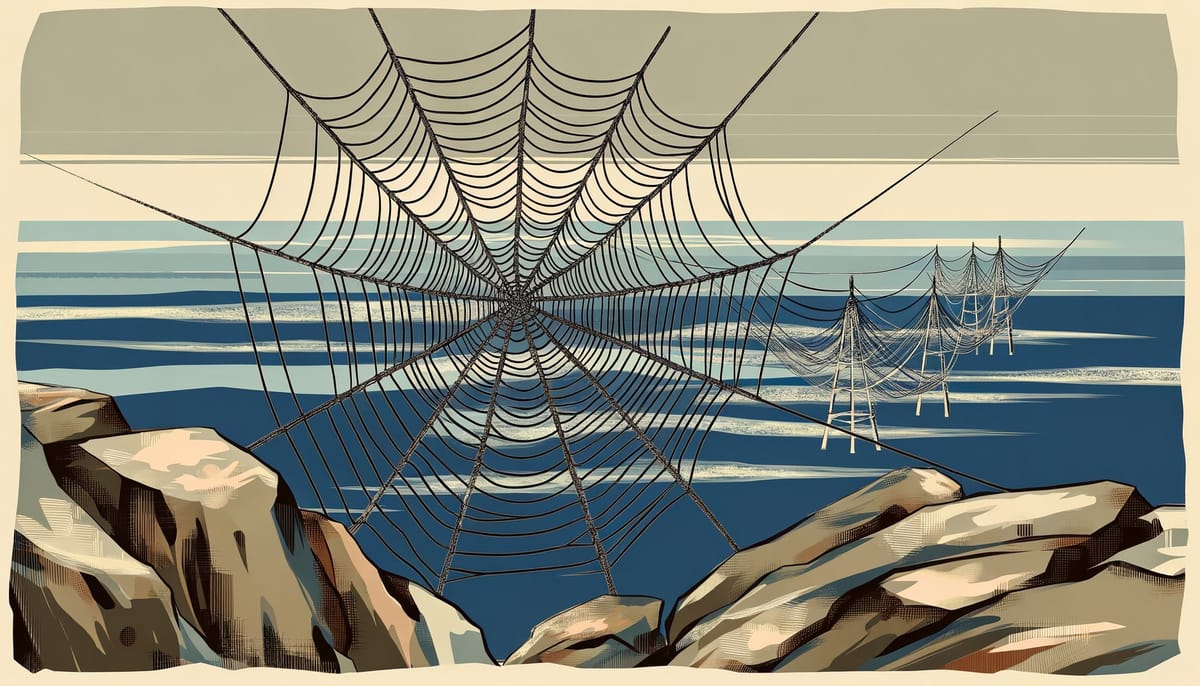

Sixteen thousand kilometers of fiber-optic cable snake beneath Philippine waters, carrying 95% of the nation’s international data traffic. These gossamer threads of glass—thinner than a human hair, buried in seabed mud or draped across abyssal plains—connect Manila’s military command centers to Washington, link the Armed Forces of the Philippines to its forward-deployed units, and bind an archipelago of 7,600 islands into something resembling a unified state. China has built a device to cut them.

The China Ship Scientific Research Centre’s “electric cutting device for deep-sea cables” uses diamond-coated grinding wheels designed to sever armored cables at depths of 4,000 meters. This is not theoretical capability. Chinese survey vessels have been documented operating near Philippine cable routes, mapping the seabed with the precision that military pre-positioning requires. The question is no longer whether Beijing could isolate the Philippines from global communications during a Taiwan crisis. The question is whether Manila could maintain command-and-control of its own forces if it tried.

The answer reveals a vulnerability that extends far beyond the Philippines—a structural weakness in how modern militaries have allowed themselves to become dependent on infrastructure they cannot protect.

Anatomy of Dependency

The Philippine military’s command architecture rests on a foundation of sand. The Armed Forces of the Philippines operates an integrated Command, Control, Communications, Computers, and Cyber/Intelligence system—C4IS in Pentagon parlance—managed by the Communications, Electronics, and Information Systems Service. CEISSAFP’s motto promises “Command and Control superiority through interoperability, integrity, and innovation.” But interoperability requires connectivity. Integrity requires secure channels. Innovation means nothing when the physical layer disappears.

Eleven international submarine cable systems currently land at nine Philippine stations. Six more are under construction. These cables cluster at predictable geographic chokepoints—Batangas, La Union, Aurora—locations determined not by military defensibility but by where the seafloor topography permits safe landings and where commercial economics favor construction. The same terrain that makes these sites ideal for cable operations makes them ideal for targeting.

The conventional understanding treats cable vulnerability as a communications problem. Sever the cables, lose internet access, switch to satellite backup. This misses the structural reality. Philippine military networks ride on civilian telecommunications infrastructure. The AFP’s secure communications depend on bandwidth leased from commercial providers whose entire business model assumes those undersea cables remain intact. When the cables go dark, so does the architecture built atop them.

Consider what happens in the first hours of a Taiwan crisis. Chinese forces would face a decision tree with cable disruption as an early branch. A blockade scenario might leave Philippine cables intact—coercion works better when the target can receive demands and communicate capitulation. But a major conflict, one involving strikes on U.S. bases in Japan and Guam, changes the calculus entirely. The Philippines hosts nine Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement sites. American forces would operate from Philippine soil. Manila’s ability to coordinate with Washington, to direct its own naval patrols, to manage the logistics of a wartime archipelago—all of this depends on communications that China has demonstrated the capability and apparent intent to destroy.

The physics are unforgiving. Submarine cables transition from buried protection in waters shallower than 200 meters to exposed vulnerability in deeper zones. This creates a detection paradox: shallow waters offer physical concealment through burial but acoustic transparency for monitoring, while deep waters reverse the equation. Chinese survey vessels have spent years mapping these transition zones. They know where the cables are. They know where they’re vulnerable. The only question is timing.

The Satellite Mirage

When officials discuss cable resilience, satellite communications appear as the obvious fallback. Starlink, OneWeb, military SATCOM—surely the Philippines can simply look up when the undersea connections fail. This confidence reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of what satellite systems can and cannot do.

Low-Earth orbit constellations like Starlink promise latency below 50 milliseconds, competitive with terrestrial fiber for many applications. But research on LEO satellite performance reveals dramatic geographic variation. Inter-satellite laser links route through distant ground stations, creating paradoxical latency spikes that transform promised tactical advantages into unpredictable delay patterns. A commander expecting real-time coordination may find himself operating on a tempo his adversary has already exploited.

Bandwidth presents the harder constraint. Undersea cables carry terabits per second. Satellite constellations offer megabits per terminal. The Philippine military’s C4IS architecture assumes bandwidth abundance—video feeds from surveillance drones, real-time intelligence fusion, simultaneous coordination across multiple theaters. Satellite backup provides a straw when the fire hose disappears.

Then there’s the sovereignty problem. SpaceX demonstrated in Ukraine that commercial satellite providers can geofence service in conflict zones. The technical mechanism that enables service boundaries becomes a private veto point over state military command-and-control. Manila would find itself dependent on Elon Musk’s willingness to maintain coverage—a willingness that Chinese diplomatic and economic pressure could test at precisely the wrong moment.

Military satellite communications offer more reliability but less capacity. The AFP’s SATCOM terminals, deployed during crises like the Marawi siege, function as centralized communication hubs rather than distributed networks. They create single points of failure at the tactical level while solving the strategic connectivity problem. A Chinese electronic warfare campaign targeting these terminals—jamming, spoofing, or simply overwhelming limited satellite capacity with noise—could degrade command-and-control even if the satellites themselves remain operational.

The deeper issue is architectural. The Philippine military designed its systems for an environment where bandwidth was cheap and connectivity was assumed. Satellite backup was meant to handle temporary outages, not sustained operations under adversary interdiction. Rebuilding the architecture for a communications-denied environment would require years of doctrinal change, equipment procurement, and training. The Taiwan crisis timeline does not offer years.

Ghost Networks

Beneath the formal military architecture lies something stranger and potentially more resilient: the informal networks that actually move information through Philippine society.

The Catholic Church operates what amounts to a parallel command structure. When Typhoon Haiyan devastated Leyte in 2013, Catholic volunteers delivered relief within 12 hours—faster than government agencies could activate their continuity-of-operations plans. The Church’s network doesn’t depend on undersea cables. It runs on relationships, on the parish structure that reaches into every barangay, on radio stations originally built for evangelization that proved resistant to state capture during martial law.

Radio Veritas, established for religious broadcasting, demonstrated during the Marcos era that its transmitter architecture and Church ownership created an inadvertent command-and-control infrastructure resistant to regime suppression. When secular media fell silent, the Church’s network kept talking. This isn’t nostalgia. It’s a template.

Amateur radio operators—ham radio enthusiasts dismissed as hobbyists—maintain communications during every typhoon that knocks out cellular towers and internet connections. These operators practice exactly the skills that military communications would require in a degraded environment: low-bandwidth burst transmissions, frequency-hopping to avoid interference, the discipline to convey essential information in seconds rather than minutes. The AFP’s formal doctrine assumes bandwidth availability. Fishermen’s participatory VHF radio nets assume scarcity. One of these assumptions will prove correct during a crisis.

The Philippine Military Academy alumni network functions as what network theorists call a “shadow routing protocol.” When official command structures fail, information flows through personal relationships forged during cadet years. Shared mental models developed through common training allow abbreviated communication—a reference that would mean nothing to outsiders conveys complete operational intent to classmates. This isn’t a designed system. It’s an emergent property of how the Philippine military actually works.

These informal networks share a characteristic that formal military communications lack: they degrade gracefully. Cut a submarine cable and the entire architecture built atop it collapses. Disrupt a relationship network and information finds alternative paths. The question is whether Philippine military doctrine recognizes this resilience or whether it remains invisible to planners focused on the formal C4IS architecture.

The Legal Void

International law offers the Philippines less protection than officials might hope. The 1884 Convention for the Protection of Submarine Cables established that damaging cables in international waters constitutes an offense, but enforcement depends entirely on flag states prosecuting their own vessels. UNCLOS Article 113 codified this framework, creating mandatory criminalization for cable damage while providing no mechanism for enforcement during armed conflict.

The structure creates an inverse incentive. Peacetime cable operations face heavy regulation with clear liability. Wartime cable operations have maximum freedom but zero accountability. The law becomes more permissive precisely when protection matters most.

Distributed Acoustic Sensing technology transforms submarine cables into continuous acoustic sensors capable of detecting vessel activity with meter-scale precision. The same fiber carrying internet traffic can identify a submarine approaching a cable route. But detection without attribution accomplishes nothing. UNCLOS requires states to criminalize damage by their own flags or persons—a requirement that assumes the damaging party can be identified and that the flag state will cooperate in prosecution. Neither assumption survives contact with Chinese gray-zone operations.

The 1884 Convention’s colonial exclusion mechanism—allowing British colonies to opt out—created a template for jurisdictional fragmentation that persists today. The original design assumed imperial coordination among treaty parties. Modern cable protection assumes nothing of the sort. Flag state enforcement gaps mean that a Chinese-flagged vessel could sever Philippine cables with minimal legal consequence, particularly if the action occurred during hostilities that provided plausible military justification.

Temporal Asymmetries

A Taiwan crisis would unfold across multiple timescales simultaneously, each creating different command-and-control requirements.

The BRP Sierra Madre, grounded on Second Thomas Shoal, requires periodic resupply missions—discrete events every few weeks, not continuous operations. Command decisions for these missions operate on a scheduled tempo. If cable disruption occurs between resupply windows, the mission can proceed on pre-established orders. If disruption coincides with a resupply attempt, tactical commanders face decisions without strategic guidance.

This temporal structure reveals a broader pattern. Chinese gray-zone tactics deliberately exploit the gap between Congress’s war declaration power and the President’s operational command authority. By maintaining operations below the threshold of war while above the threshold of peace, Beijing creates constitutional ambiguity that cable disruption would amplify. Who authorizes military response when communications with Manila are degraded? What happens when tactical commanders cannot confirm whether the nation is at war?

The RAND Corporation’s analysis suggests “it’s very hard to imagine a scenario where the Philippines will not somehow get involved” in a Taiwan crisis. Geographic proximity and alliance obligations make neutrality nearly impossible. But involvement without communication creates a worst-case scenario: Philippine forces committed to operations they cannot coordinate, taking actions that might escalate or de-escalate without strategic guidance, operating on assumptions that events have already invalidated.

The repair timeline compounds the problem. Submarine cable repair vessels cost approximately $100,000 per day to operate. The global fleet of these specialized ships is small. During a Taiwan crisis, demand would spike while supply remained fixed. Lloyd’s Joint War Committee designation of the Taiwan Strait as a Listed Area would trigger insurance exclusions that ground commercial repair operations entirely. The Philippines could find its cables severed with no realistic prospect of repair for months or years.

Resilience Pathways

Three intervention points offer genuine leverage, each with costs that Philippine planners must weigh honestly.

First, doctrinal reform. The AFP could adopt mission command principles that push decision authority to tactical commanders, reducing dependence on real-time strategic guidance. This requires accepting that subordinate commanders will make decisions that higher headquarters might not endorse—a cultural shift that challenges both the AFP’s institutional hierarchy and the Catholic cultural substrate that shapes Filipino military culture. The PLA has struggled to adopt mission command despite doctrinal commitment. The AFP faces the same structural challenge with additional cultural headwinds.

Second, infrastructure hardening. The Philippines could require cable landing station diversification, mandate backup power and communications for critical nodes, and invest in the terrestrial microwave links that could provide inter-island connectivity when undersea cables fail. This costs money the defense budget doesn’t have. It requires regulatory authority the government hasn’t established. The National Cybersecurity Plan 2023-2028 identifies critical infrastructure protection as a priority, but identification is not implementation.

Third, alliance integration. Deeper embedding of Philippine command-and-control within U.S. military networks could provide redundancy through American satellite and communications infrastructure. This trades one dependency for another. It raises sovereignty concerns that Philippine domestic politics make explosive. And it assumes American communications would remain available during a crisis that might see U.S. systems targeted as vigorously as Philippine ones.

None of these options is sufficient alone. All require resources, political will, and time that the current trajectory does not provide.

The Default Future

Without intervention, the Philippines enters any Taiwan crisis with a command-and-control architecture that Chinese forces can degrade at will. The AFP would retain local tactical communications—radios work without undersea cables—but lose the strategic coordination that transforms individual units into a coherent force. Naval vessels at sea would operate on last-known orders. Air defense sites would lack integrated threat pictures. The government would struggle to communicate with its own population, ceding the information environment to adversaries with satellite broadcast capability.

The informal networks—Church, ham radio, alumni connections—would partially compensate. Information would flow, slowly and imperfectly, through channels that Chinese electronic warfare cannot easily target. But these networks were not designed for military command. They carry social information, not tactical data. They enable coordination, not control.

The most likely scenario is not total communications blackout but degraded, unpredictable connectivity that creates worse problems than complete isolation. Commanders would never know whether their orders arrived, whether their reports reached higher headquarters, whether the strategic picture they remembered remained accurate. They would face decisions with partial information and no way to verify what they thought they knew.

This uncertainty creates escalation risk. A tactical commander who believes his nation is at war may take actions appropriate to that belief. A tactical commander who believes peace persists may fail to respond to attacks. Both errors become more likely when communications degrade. The Philippines could find itself escalating a conflict it sought to avoid, or failing to defend itself against aggression it didn’t recognize in time.

FAQ: Key Questions Answered

Q: How quickly could China sever Philippine undersea cables? A: Chinese survey vessels have mapped Philippine cable routes for years, and the deep-sea cutting device unveiled by Chinese researchers can operate at depths of 4,000 meters. Severing multiple cables simultaneously would require pre-positioned assets, but the technical capability exists for rapid, coordinated disruption within hours of a decision to act.

Q: Could Starlink replace undersea cables for military communications? A: Not adequately. Satellite constellations provide megabits of bandwidth where cables provide terabits. Military C4IS architecture assumes bandwidth abundance that satellites cannot match. Additionally, commercial providers like SpaceX retain the ability to geofence service, creating sovereignty concerns during conflict.

Q: What happens to the Philippine economy if cables are cut? A: The business process outsourcing industry—a major employer and foreign exchange earner—would collapse immediately. Banking, logistics, and government services that depend on international connectivity would degrade. Economic disruption would compound military challenges by straining the social fabric the government must maintain during crisis.

Q: Does the U.S.-Philippines Mutual Defense Treaty cover cable attacks? A: The treaty covers “armed attack in the Pacific Area” but does not specify whether infrastructure sabotage below the threshold of conventional military action triggers mutual defense obligations. Gray-zone cable disruption would create precisely the ambiguity that complicates alliance response.

The Quiet Severance

The vulnerability is not secret. Philippine officials discuss it in conferences. American analysts write reports about it. Chinese strategists presumably read both. Yet the cables remain exposed, the backup systems remain inadequate, and the doctrinal reforms remain theoretical.

This gap between awareness and action reflects a deeper pattern in how democracies prepare for conflicts they hope to avoid. Investment in resilience acknowledges the possibility of war, which carries political costs. Visible preparations might provoke the adversary they’re meant to deter. And the timeline for infrastructure hardening extends beyond electoral cycles that reward immediate results over long-term security.

The Philippines is not unique in this failure. Every nation whose military depends on civilian telecommunications infrastructure faces the same structural vulnerability. But geography makes the Philippine case acute. The archipelago cannot function without communications that cross water. The Taiwan Strait sits hours away by ship. And the adversary has built a device specifically designed to exploit this weakness.

When the cables go dark, the question will not be whether Manila anticipated the attack. Everyone anticipated it. The question will be whether anticipation translated into preparation—or whether awareness remained, until the end, merely awareness.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- South China Morning Post investigation of China’s deep-sea cable cutter - primary source on Chinese cable-cutting capability

- RAND Corporation analysis on Philippine involvement in Taiwan scenarios - strategic assessment of Philippine alliance obligations

- Internet Society research on LEO satellite latency - technical analysis of satellite communications limitations

- Philippine National Cybersecurity Plan 2023-2028 - government framework for critical infrastructure protection

- NOAA overview of submarine cable international framework - legal context for cable protection under UNCLOS

- International Cable Protection Committee archives on 1884 Convention - historical legal framework

- CNAS report on regional responses to Taiwan contingency - scenario analysis for major conflict

- Licas News on Catholic Church typhoon response - documentation of informal network resilience