The Invisible Tripwire: How China's Cable Control Erodes South China Sea Deterrence

China's ability to sever or tap Southeast Asian undersea cables creates pre-conflict leverage that degrades allied coordination without triggering retaliation. The advantage is quiet, legal, and growing.

The Invisible Tripwire

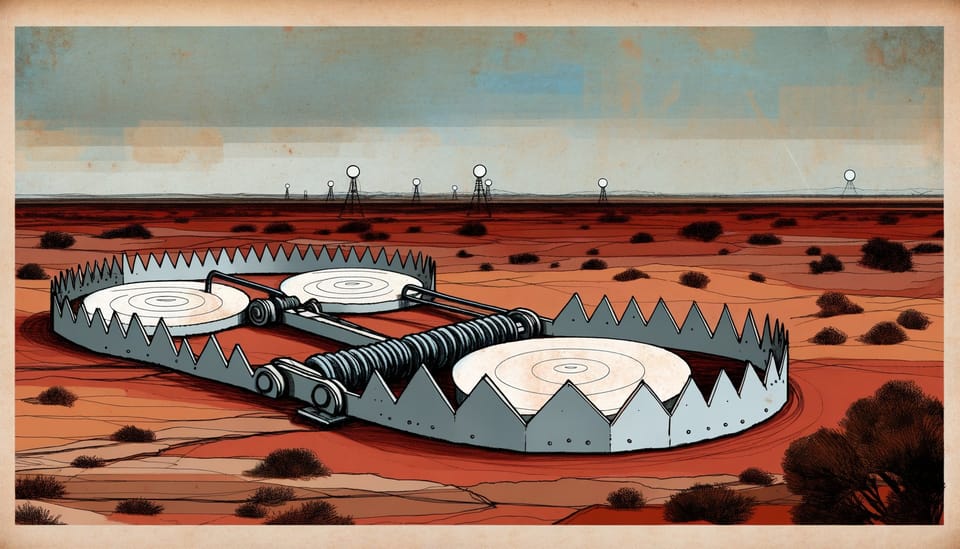

In March 2025, Chinese researchers at the China Ship Scientific Research Center published something unusual: a detailed technical paper describing a device capable of severing armored undersea cables at depths exceeding 4,000 meters. The diamond-coated grinding wheel on a titanium alloy chassis was not, strictly speaking, news. Intelligence agencies had long assumed such capabilities existed. What startled Western analysts was the publication itself. China was announcing, not concealing, its ability to cut the digital arteries connecting Southeast Asia to the world.

This was not carelessness. It was signaling.

The question now confronting strategists in Washington, Tokyo, and Canberra is whether this capability—combined with China’s expanding control over cable repair infrastructure and its assertive permitting regime in contested waters—fundamentally undermines deterrence in the South China Sea. The conventional wisdom holds that deterrence requires credible threats of retaliation. But what if an adversary can blind you before the fight begins?

The Architecture of Vulnerability

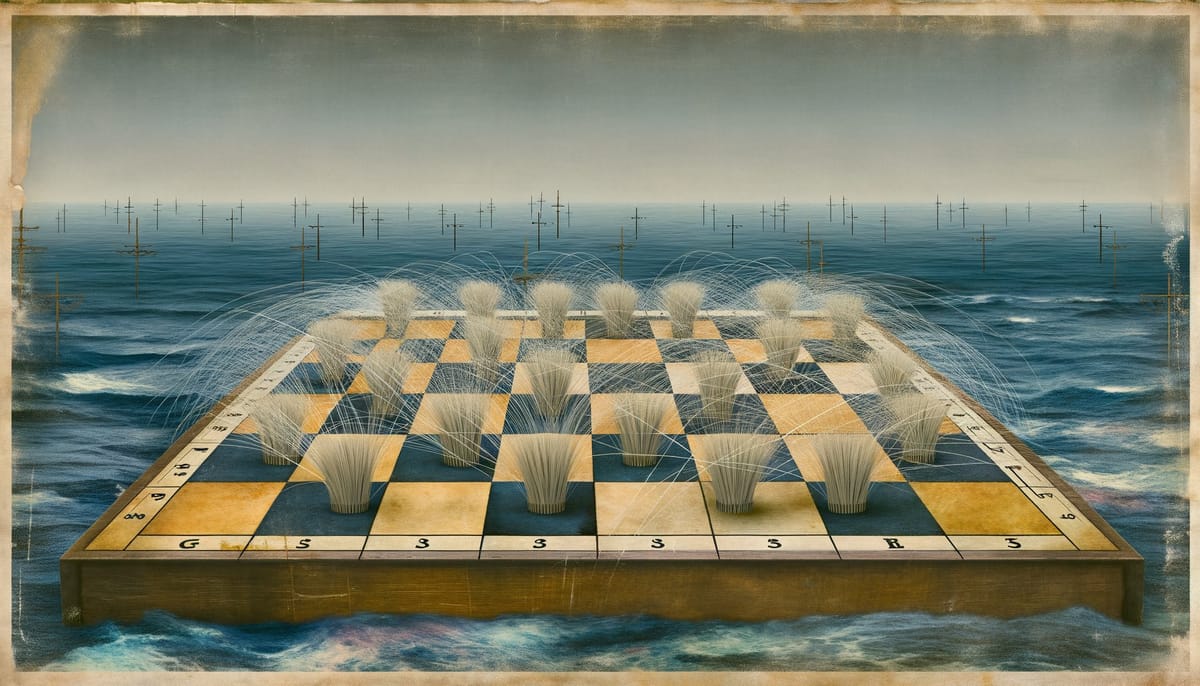

Undersea cables carry over 99 percent of intercontinental data. This is not a metaphor for importance; it is a statement of physical fact. Satellites, despite their strategic value, handle less than one percent of global data traffic. The bandwidth simply isn’t there. When American and allied forces in the Pacific communicate, coordinate logistics, share intelligence, and execute the intricate choreography of modern warfare, they depend on fiber-optic threads thinner than a garden hose, lying exposed on the seabed.

Southeast Asia’s cable geography concentrates risk in ways that favor China. Singapore alone hosts approximately 28 cables, with at least 13 more under construction. These cables converge at landing stations within 200 meters of shore—physical chokepoints where multiple systems become vulnerable to a single strike. The region’s cables transit waters where China claims sovereignty under its nine-dash line, creating jurisdictional ambiguity that Beijing has learned to exploit.

The conventional understanding treats cable vulnerability as a wartime problem. This is incomplete. China’s advantage operates across the conflict spectrum, from peacetime shaping through crisis signaling to kinetic action. The March 2025 capability disclosure fits a pattern: establish the credible threat, then leverage it for coercion without ever cutting a single cable.

Consider the repair bottleneck. The global cable repair fleet consists of fewer than 60 specialized vessels, and China controls a growing share of this capacity. When cables break—as they do regularly, from anchors, earthquakes, and fishing trawlers—repair requires permits from coastal states, access to replacement equipment, and weeks of specialized work. China has already demonstrated willingness to delay repair authorizations in the South China Sea. A cable cut in contested waters could remain severed not for days but for months, as diplomatic negotiations over repair access drag on.

The Carnegie Endowment’s analysis documents how geopolitical tensions have begun limiting Chinese participation in major cable projects. But this cuts both ways. As Western-backed consortiums route new cables around Chinese-claimed waters, they inadvertently reinforce Singapore’s centrality as the alternative convergence point. The hub becomes more critical, not less vulnerable.

The Doctrine Behind the Device

Understanding why cable control matters to Beijing requires understanding how the People’s Liberation Army thinks about modern conflict. PLA doctrine emphasizes what it calls “systems confrontation”—the targeting of an adversary’s operational systems rather than individual platforms. Destroy the network, and the platforms become isolated nodes incapable of coordinated action.

The Information Support Force, created in 2024 from the reorganization of the Strategic Support Force, integrates cyber, electronic warfare, and space capabilities under unified command. Its doctrine treats information dominance as the precondition for victory in any domain. Cable infrastructure fits this framework precisely: it is the substrate on which American command-and-control depends, and it is vulnerable in ways that satellites and hardened military networks are not.

Chinese strategists have studied the Serbian penetration of NATO networks during the Kosovo War with particular interest. The lesson they drew was not about cyber defense but about asymmetric opportunity. Networks create strategic parity regardless of conventional force disparities. A nation that cannot match American carrier groups can nonetheless blind them.

The operational logic runs as follows: in the opening hours of a conflict over Taiwan or the South China Sea, sever key cables connecting Southeast Asian allies to American command infrastructure. Simultaneously, degrade satellite links through kinetic or electronic means. Allied forces would not be destroyed—they would be disconnected. Unable to coordinate, share targeting data, or receive updated intelligence, they would fight as isolated units against a networked adversary.

This is not speculation. The CSIS analysis of China’s Digital Silk Road documents how Beijing has systematically invested in cable landing stations, data centers, and repair capabilities across the region. The pattern suggests preparation for exactly this scenario.

The Deterrence Dilemma

Classical deterrence theory assumes that adversaries can calculate costs and benefits clearly. Threaten sufficient retaliation, and rational actors will refrain from aggression. But cable vulnerability introduces asymmetries that distort this calculus in China’s favor.

First, attribution. When a cable fails, determining cause takes time. Anchors drag across seabeds constantly; earthquakes rupture cables without warning; fishing trawlers snag lines they cannot see. The forensic window for distinguishing sabotage from accident is narrow—days to weeks before marine growth and corrosion obscure mechanical signatures. China could sever cables and maintain plausible deniability long enough to achieve operational objectives.

Second, escalation thresholds. Under international law, cable damage in peacetime is a criminal matter requiring flag-state prosecution. It does not trigger mutual defense obligations. The U.S.-Philippines Mutual Defense Treaty’s Article 5 requires demonstrating an “armed attack”—a standard that ambiguous cable cuts may not meet. This creates a legal vacuum where sabotage falls into a non-escalatory zone by design.

Third, temporal asymmetry. Cable repairs take weeks. Military operations unfold in hours. By the time repair ships arrive and negotiate access, the strategic situation may have already been decided. China’s permit delays can weaponize bureaucracy itself, creating lag that compounds the physical repair timeline.

The American deterrence posture in the South China Sea rests on forward-deployed forces, allied partnerships, and the threat of escalation dominance. But if China can degrade the information architecture connecting these elements before hostilities begin, the credibility of American responses diminishes. You cannot coordinate a coalition response if the coalition cannot communicate.

Lloyd Austin, the U.S. Secretary of Defense, has emphasized “integrated deterrence”—combining military, diplomatic, economic, and technological capabilities across allies and domains. The concept assumes integration is possible. Cable vulnerability suggests it may not be, at least not reliably.

The Gray Zone Advantage

China’s cable leverage operates most powerfully in the gray zone between peace and war. Outright cable-cutting in peacetime would be provocative and attributable. But subtler forms of infrastructure coercion achieve similar effects without crossing thresholds that demand response.

The THAAD precedent is instructive. When South Korea deployed American missile defense systems in 2016-2017, China responded with informal sanctions—regulatory harassment of Korean businesses, tourism restrictions, customs delays—that imposed significant costs while remaining officially deniable. The playbook worked. It established that China could punish perceived provocations through distributed, plausibly unofficial means.

Cable infrastructure offers similar opportunities. Delayed repair permits. Regulatory complications for cable landing stations. Preferential treatment for Chinese-owned repair vessels. Subsidized competition that undercuts Western cable operators. None of these actions constitutes an armed attack. All of them degrade the resilience of the regional information architecture.

The Lowy Institute’s analysis documents how Chinese cable investments have created dependencies that complicate allied responses. When a Southeast Asian nation’s primary internet connectivity runs through Chinese-built infrastructure, the cost-benefit calculation for joining American-led initiatives shifts. This is coercion through infrastructure, not arms.

Zhang Youxia, Vice Chairman of China’s Central Military Commission and one of the few PLA generals with actual combat experience, has overseen the evolution of China’s information warfare capabilities. His emphasis on “information confrontation parity” reflects a strategic judgment: China need not match American conventional forces if it can neutralize the information systems that make those forces effective.

What Breaks First

If current dynamics continue, the trajectory points toward progressive erosion of allied information resilience rather than dramatic rupture. China is unlikely to sever cables in peacetime—the provocation would be too clear, the retaliation too certain. Instead, it will continue building leverage: more repair capacity, more landing station investments, more regulatory influence over cable routes.

The breaking point arrives during a crisis. Imagine a confrontation over Taiwan or a disputed South China Sea feature. As tensions escalate, cables begin failing—one here, another there, each incident ambiguous enough to avoid triggering alliance commitments. Repair ships are delayed by permit complications. Satellite links experience unexplained degradation. Allied forces find their coordination degrading precisely when they need it most.

The cascade would not be dramatic. It would be quiet. Communications would become unreliable rather than impossible. Intelligence would arrive late rather than never. Targeting data would be hours old rather than real-time. The effect would be to slow allied decision-making, disrupt operational tempo, and create windows of opportunity for Chinese action.

The economic dimension compounds the military problem. Research on infrastructure disruption shows that even brief outages trigger disproportionate public anxiety and political pressure. Social media amplifies uncertainty. Markets react to rumors. Governments face domestic pressure to de-escalate, even when strategic logic argues for resolve. Cable vulnerability becomes a tool for psychological warfare as much as operational degradation.

Intervention Points

Three leverage points could alter this trajectory, though none comes without cost.

Diversified routing. The Quad partners—the United States, Japan, Australia, and India—have begun coordinating on cable resilience, including standardized security clauses and preferred vendor lists. New cables could route through waters where Chinese claims are weaker, reducing exposure to permit manipulation. The cost: longer routes mean higher latency and greater expense. Financial markets, which depend on millisecond advantages, would resist. The trade-off is security versus efficiency, and efficiency has powerful constituencies.

Dedicated military infrastructure. American and allied forces could reduce dependence on commercial cables by investing in dedicated military communication systems—hardened cables, expanded satellite constellations, high-frequency radio backups. The Pentagon has explored using existing telecommunications cables as distributed acoustic sensors for submarine detection, a dual-use approach that would justify greater investment. The cost: billions of dollars and years of construction. The trade-off is resilience versus resources that could fund other capabilities.

Legal and normative pressure. The 1884 Convention for the Protection of Submarine Telegraph Cables and UNCLOS Article 113 establish that willful cable damage is criminal. But enforcement depends on flag states prosecuting their own vessels—a mechanism China can easily circumvent. A concerted diplomatic effort to strengthen international norms, perhaps including cable protection in maritime security dialogues, could raise the reputational cost of interference. The cost: diplomatic capital expended on an issue that lacks public salience. The trade-off is normative investment versus more visible priorities.

The most likely scenario is incremental adaptation rather than strategic transformation. The Quad will fund some new cables. The Pentagon will invest in some backup systems. Diplomats will issue some statements about cable protection. None of it will fundamentally alter the asymmetry. China will retain its pre-conflict advantage, and deterrence will depend increasingly on American willingness to escalate despite degraded information architecture.

This is not deterrence failure in the classical sense. It is deterrence erosion—a gradual shift in the balance of capabilities and resolve that makes conflict more likely without making it inevitable.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Can’t satellites replace undersea cables if they’re cut? A: Not remotely. Satellites carry less than one percent of intercontinental data traffic because they lack the bandwidth. A single modern undersea cable can transmit more data than all active communications satellites combined. Satellite backup exists for critical military communications, but it cannot sustain the volume required for coordinated coalition operations or civilian economic activity.

Q: How long does it take to repair a severed undersea cable? A: Typically two to four weeks under normal conditions, but this assumes available repair ships, granted permits, and accessible locations. In contested waters where China controls permitting or deploys vessels that complicate access, repairs could take months. The repair bottleneck is as strategically significant as the initial cut.

Q: Would cutting cables be an act of war? A: Under current international law, probably not. Cable damage in peacetime is treated as a criminal matter under UNCLOS Article 113, requiring flag-state prosecution rather than triggering mutual defense obligations. This legal gray zone is precisely what makes cable interference attractive—it imposes costs without crossing thresholds that demand military response.

Q: Why did China publicly reveal its cable-cutting capability? A: Effective deterrence requires demonstrating capability. By publishing technical details of its deep-sea cutting device, China signals to potential adversaries that cable infrastructure is vulnerable, potentially deterring actions Beijing opposes without ever using the capability. The disclosure is strategic communication, not operational carelessness.

The Wires Beneath the Waves

The South China Sea’s strategic balance has always been measured in ships, aircraft, and missiles. These remain decisive. But beneath the surface, a quieter competition is underway—one measured in fiber-optic strands, repair vessel availability, and regulatory leverage over landing stations.

China’s cable capabilities do not make deterrence unworkable. They make it more expensive, more uncertain, and more dependent on American willingness to act despite degraded information. The pre-conflict advantage is real but not absolute. It shifts the balance without determining the outcome.

What it does determine is the character of any future crisis. When tensions rise in the South China Sea, the first moves will not be visible from satellites or announced in press conferences. They will occur in the quiet bureaucracies that grant repair permits, in the unexplained failures of redundant systems, in the gradual dimming of the networks that connect allies to each other and to their own forces.

The cables will not be cut. They will simply become unreliable at the moment reliability matters most. That is the advantage China has built, and that is the vulnerability the United States has yet to address.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- Carnegie Endowment Southeast Asia Cable Study - comprehensive analysis of regional cable infrastructure and geopolitical tensions

- CSIS Analysis of China’s Digital Silk Road - documentation of Chinese cable investments across Southeast Asia

- Lowy Institute Cable Analysis - examination of infrastructure dependencies created by Chinese investments

- CEIAS Report on Cable-Cutting Device - analysis of the China Ship Scientific Research Center’s technical disclosure

- Securing the Backbone: Cyber Resilience in Contested Logistics - research on infrastructure disruption and operational resilience

- The Diplomat on Digital Sovereignty - regional perspectives on data and infrastructure control

- ORF Digital Silk Road Analysis - mapping of China’s vision for technology expansion