The Invisible Colleague: Second-Order Consequences of AI Agents in the Workforce

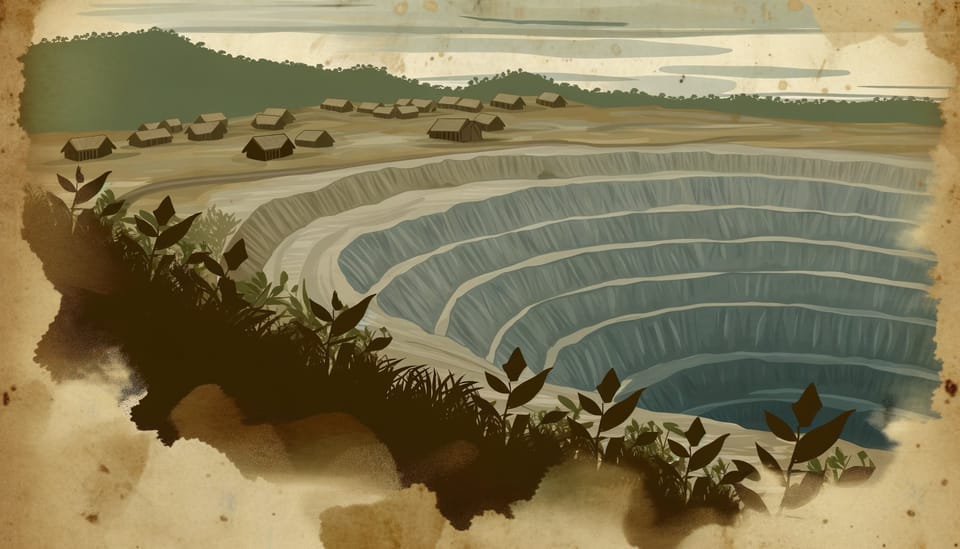

As AI agents move from augmenting human work to replacing it, the visible efficiency gains obscure deeper structural shifts: fractured career pipelines, gamified hiring systems, new forms of political dependency, and the quiet collapse of institutional knowledge transfer.

The Invisible Colleague

In January 2025, a mid-sized accounting firm in Milwaukee quietly reassigned its entire junior analyst pool. Not fired—reassigned. The spreadsheet reconciliations, the preliminary audit checks, the endless formatting of quarterly reports: all now handled by an AI agent that cost less per month than one analyst’s health insurance. The analysts themselves were moved to “client relationship roles,” a euphemism that fooled no one. Within six months, three had left for graduate school, two had pivoted to sales, and one had started a YouTube channel about personal finance. The firm’s productivity rose 34%. Its institutional knowledge began to evaporate.

This scene, multiplied across thousands of organizations, captures the strange duality of AI agents entering the workforce in 2025. The first-order effects are visible and measurable: tasks automated, costs reduced, output increased. But the second-order consequences—the cascading shifts in how work is organized, how skills are valued, how careers are built, how societies cohere—remain largely invisible until they aren’t. By then, the architecture has already changed.

The Metabolic Collapse

The conventional narrative frames AI agents as sophisticated tools: faster spreadsheets, smarter search engines, tireless assistants. This framing is not wrong. It is catastrophically incomplete.

What distinguishes the 2025 wave from previous automation is not capability but autonomy. Earlier AI systems augmented human decision-making. The new agents replace it. They don’t just process data; they interpret context, prioritize tasks, execute multi-step workflows, and learn from outcomes. A customer service agent doesn’t just suggest responses—it handles the entire interaction, escalating to humans only when confidence drops below threshold. A legal research agent doesn’t just find relevant cases—it drafts the brief, flags weaknesses, and suggests counterarguments.

This shift creates what organizational theorists call a “metabolic discontinuity.” Traditional automation eliminated specific tasks while preserving the human role as coordinator. AI agents eliminate coordination itself. The middle layer of work—the synthesis, the judgment calls, the institutional translation—becomes optional.

Consider the mathematics. Human workers require approximately 2,000 calories daily to function, translating to a biological floor beneath which compensation cannot fall without literal starvation. AI inference costs have dropped to roughly $1 per day for capabilities matching junior professional work. This isn’t a 10% efficiency gain. It’s a structural disconnect between the cost of human survival and the cost of equivalent output.

The Milwaukee accounting firm discovered this arithmetic accidentally. So did a marketing agency in Austin, a logistics company in Rotterdam, and a legal services provider in Singapore. None set out to eliminate jobs. All found themselves unable to justify the cost differential once agents proved reliable. The decision made itself.

What breaks first is not employment—unemployment rates in early 2025 remain stable—but the pathway to employment. Entry-level positions exist to train people for senior roles. When agents absorb entry-level work, the training pipeline fractures. A law firm that uses AI for document review no longer needs first-year associates doing document review. But first-year associates doing document review is how lawyers learn to become partners.

This creates a temporal trap. The effects won’t appear in this quarter’s employment statistics. They will appear in 2030’s partnership tracks, in 2035’s executive pipelines, in 2040’s institutional competence. The juniors who never learned the craft cannot teach the next generation. The knowledge doesn’t disappear—it was never acquired.

The Gamification Paradox

Transparency requirements were supposed to make AI hiring fairer. They have made it gameable.

When regulators in New York, Illinois, and Colorado mandated that AI hiring systems provide candidates with feedback—explaining why they were rejected, what factors mattered, what might improve their scores—they created something unprecedented: a technical manual for system manipulation. The push for “explainable AI” that offers counterfactual guidance (“change X to improve your score”) inadvertently publishes the algorithm’s preferences.

Candidates responded rationally. LinkedIn profiles began optimizing for known AI preferences. Resume formatting shifted toward machine-readable structures. Interview preparation services now include “AI coaching” modules that teach candidates to trigger favorable algorithmic responses. A cottage industry emerged around reverse-engineering hiring systems.

The result is credential inflation at unprecedented velocity. Stanford research shows a 6% employment boost from LinkedIn credential sharing—but this success signal drives more sharing, which drives more credentials, which dilutes the signal. Micro-credentials that once differentiated candidates now merely qualify them for consideration. The bar rises continuously.

This dynamic interacts toxically with the metabolic discontinuity. As entry-level positions vanish, competition for remaining slots intensifies. As competition intensifies, credential requirements escalate. As requirements escalate, candidates invest more in signaling. As signaling investment rises, the correlation between credentials and actual capability weakens. Employers respond by adding more screening layers. The spiral tightens.

The impossibility theorem haunts every attempt at fairness. Mathematical proof demonstrates that multiple fairness metrics—sufficiency, separation, calibration—cannot be simultaneously satisfied except under conditions of equal base rates across groups. Since base rates are not equal (different demographic groups have different historical access to credentials, networks, and opportunities), any algorithmic intervention that optimizes for one fairness criterion necessarily degrades another.

Disparate impact liability thus creates a structural trap. A system calibrated for predictive accuracy will show disparate impact. A system adjusted to eliminate disparate impact will lose predictive accuracy. A system attempting both will achieve neither. Regulators demanding “fair AI” are demanding mathematical impossibilities. The compliance response is not to solve the problem but to document the attempt.

The Sovereignty Crisis

AI agents require compute. Compute requires data centers. Data centers require power and water. These physical requirements are creating new forms of political dependency that nobody anticipated.

Google’s data center in The Dalles, Oregon, consumes water at rates that triggered municipal litigation. The “lengthy legal battle” over water permits revealed something profound: local water authorities now exercise de facto constitutional authority over national AI infrastructure decisions. A city council in rural Oregon can constrain Google’s global AI capabilities by denying permits. This is not how sovereignty is supposed to work.

The geographic concentration of GPU capacity in American and European data centers forces a choice on every other nation: technological advancement (pilgrimage to foreign compute) or data sovereignty (staying local with inferior resources). Neither option is acceptable. Both are unavoidable.

China’s response has been instructive. Its temporary liberalization of rare earth exports—after triggering Western investment in alternative supply chains—created a potlatch-like cycle. The “gift” of resumed exports forced recipients into costly counter-gifts: continued investment in now-uneconomical alternatives, or dependence on a supplier who has demonstrated willingness to weaponize supply. The strategic withdrawal after provoking reaction is more damaging than sustained restriction would have been.

Grid synchronization requirements transform technical compatibility into inherited political obligation. Once electrical systems synchronize—matching frequency and voltage to create “grid communities”—disconnection becomes a coercive weapon rather than a neutral option. The same logic applies to AI infrastructure. Once organizations depend on specific cloud providers, migration costs create lock-in that resembles vassalage more than vendor relationships.

The carbon mathematics compound these dependencies. AI infrastructure’s energy consumption is increasing at 15-20% annually. Data center waste heat recovery systems require proximity to viable heating networks, creating selection mechanisms where facilities locate in already-developed urban cores. But communities proximate enough to receive “beneficial” waste heat are also those already experiencing urban heat island effects. The infrastructure that promises efficiency delivers environmental burden to those least able to refuse it.

The Hollow Middle

Middle management is not a hierarchical layer. It is a compositional necessity—the mechanism that translates strategic intent into operational reality and operational feedback into strategic adjustment. AI agents are eliminating this translation function.

The pattern resembles muqarnas, the Islamic architectural technique that creates complex three-dimensional forms from aggregations of simpler pieces. Muqarnas are not intermediary layers; they are compositional fields that enable geometric impossibility. Middle managers function similarly: they enable organizational complexity that would otherwise collapse into chaos or rigidity.

When agents absorb coordination tasks, organizations initially celebrate efficiency gains. Executives communicate directly with operational systems. Feedback loops tighten. Decision cycles accelerate. Then the problems emerge.

The first symptom is context collapse. Agents optimize for explicit metrics. Middle managers optimized for implicit understanding—the political sensitivities, the historical grievances, the unwritten rules that make organizations function. When a regional sales director knew that the Chicago office had a feud with the Detroit office, she routed communications accordingly. The agent sees only org charts.

The second symptom is knowledge evaporation. Organizations losing middle managers lose not just explicit procedures but somatic competence—the body’s ability to act without conscious thought. Workers experience identity loss and grief. Organizations experience phantom limb syndrome: reaching for capabilities that no longer exist, feeling pain in structures that have been amputated.

The third symptom is feedback blindness. Middle managers filtered upward, translating operational noise into strategic signal. Agents transmit everything or nothing. Executives drown in data or starve for insight. The calibration function—knowing what matters—disappears.

Unions have recognized this threat faster than management. The AFL-CIO’s 2024 framework emphasizes “worker input in AI design,” but the deeper demand is for preservation of the compositional layer. Memoranda of understanding increasingly include provisions requiring human review of agent decisions—not because humans decide better, but because the review process maintains the translation function that makes organizations coherent.

The Temporal Incommensurability

Different actors experience AI transformation on different timescales. This temporal incommensurability may be the deepest second-order consequence.

Technology companies operate on quarterly release cycles. Venture capital operates on seven-year fund horizons. Regulators operate on legislative calendars. Workers operate on career timescales of decades. Educational institutions operate on generational timescales. Indigenous communities operate on ancestral timescales that extend backward and forward beyond individual lifespans.

These temporal frames are not merely different speeds. They are different ontological realities. A policy that appears reasonable on a quarterly basis—say, rapid AI deployment to capture market share—may be catastrophic on a generational basis. A response that seems adequate on a legislative calendar may be meaningless on a technological one.

The Zapatista water resistance movements offer an unexpected parallel. Indigenous temporal sovereignty operates by refusing synchronization with extractive timescales. Communities that resist quarterly reporting cycles and electoral calendars maintain autonomy precisely through temporal misalignment. Labor unions, by contrast, have structurally embedded themselves within the same quarterly and annual bargaining rhythms that drive the displacement they oppose. They are negotiating on their opponents’ calendar.

This creates a strategic asymmetry. Organizations deploying AI agents can iterate faster than institutions can respond. By the time regulators understand a problem, the technology has evolved. By the time workers retrain, the skills have depreciated. By the time educational curricula update, the field has transformed.

The varve chronology parallel is precise. Geologists can only correct dating errors after correlating multiple cores—retrospective correction through accumulated evidence. Similarly, the second-order consequences of AI agents can only be identified after they manifest. But manifestation takes years. By the time the pattern becomes visible, the architecture has already changed.

The Apprenticeship Collapse

Traditional knowledge transfer resembled mycelial networks: bidirectional nutrient flows connecting experienced practitioners with novices, creating feedback loops that enriched both. AI systems designed to capture tacit knowledge from retiring experts break this architecture.

The capture systems work as advertised. They extract knowledge from experts, encode it in retrievable formats, and make it available to successors. What they cannot do is create the bidirectional flow that makes apprenticeship generative. The expert gives; the system takes; nothing returns. The novice receives; the system provides; no relationship forms.

This matters because tacit knowledge is not merely information. It is judgment developed through feedback, intuition refined through correction, wisdom accumulated through failure. A system that captures what an expert knows cannot capture how the expert learned it. The product survives; the process dies.

The accounting firm in Milwaukee discovered this eighteen months after deployment. The AI handled routine work flawlessly. But when unusual situations arose—the kind that require judgment rather than procedure—no one knew what to do. The partners who might have guided junior analysts through ambiguous cases had retired. The junior analysts who might have developed judgment through such guidance had been reassigned. The AI that handled routine work could not handle exceptions. The institutional capacity to handle exceptions had atrophied.

This is not a resource problem. It is an activation problem. The knowledge exists somewhere—in retired experts, in documentation, in the AI system itself. But the human capacity to deploy that knowledge in novel situations requires development that the new architecture prevents.

The professional obsolescence insurance products emerging in 2025 reveal the market’s assessment. Structured like tontines—paying out when a professional category drops below threshold—they create perverse countdown mechanisms. The more professionals exit a field, the more valuable the insurance becomes, the more incentive remaining professionals have to exit. The instrument designed to cushion displacement accelerates it.

The Fork

Two paths diverge from 2025. Neither is comfortable.

The first path accepts AI agents as permanent features of the labor landscape and redesigns institutions accordingly. This means universal basic income or equivalent income floors, since wage labor cannot sustain populations when labor costs approach zero. It means educational systems focused on capabilities agents cannot replicate: physical presence, emotional connection, creative synthesis, ethical judgment. It means regulatory frameworks that treat agent deployment like environmental impact—requiring assessment, mitigation, and ongoing monitoring.

The trade-offs are severe. UBI at scale requires taxation that capital will resist and may evade. Educational transformation takes decades. Regulatory frameworks struggle with technologies that evolve faster than rules can be written. The transition period—perhaps twenty years—will be brutal for those caught between systems.

The second path attempts to preserve human labor through artificial constraints: requirements for human-in-the-loop review, quotas for human employment, restrictions on agent autonomy. This path maintains familiar structures but at escalating cost. Organizations forced to employ humans for tasks agents could handle will lose competitiveness to those without such constraints. Nations that restrict agent deployment will fall behind those that don’t. The constraints become competitive disadvantages that erode political support for maintaining them.

The mathematics are brutal. Either path imposes costs. The first path imposes costs on workers during transition and on capital permanently. The second path imposes costs on organizations immediately and on societies eventually. Neither path avoids the fundamental discontinuity: human labor is becoming optional for an expanding range of tasks.

The most likely scenario combines the worst of both paths. Piecemeal regulation that varies by jurisdiction, creating arbitrage opportunities. Partial income support that cushions some displacement while leaving others exposed. Educational reform that arrives too late for current workers and may be obsolete for future ones. A muddle, in other words. The characteristic democratic response to structural transformation.

The Quiet Transformation

The accounting firm in Milwaukee did not set out to transform the labor market. It set out to reduce costs and improve efficiency. Multiply that decision by millions of organizations, and the transformation happens without anyone choosing it.

This is how structural change works. No conspiracy, no master plan, no villain. Just rational actors responding to incentives, each decision sensible in isolation, the aggregate incomprehensible until it’s irreversible.

The junior analysts reassigned to “client relationship roles” understood this intuitively. They were not fired. They were not mistreated. They were simply… redirected. The path they had expected—learning the craft through grinding work, developing judgment through repetition, rising through demonstrated competence—had closed. A new path opened, but no one knew where it led.

Perhaps they will find meaningful work in the new landscape. Perhaps the YouTube channel about personal finance will succeed. Perhaps the graduate degrees will open doors that the old path would have closed. Structural transformations create losers, but they also create winners. The distribution is what politics determines.

What cannot be determined is whether to have the transformation at all. The AI agents are here. They work. They cost less. Organizations that refuse to use them will be outcompeted by organizations that don’t. The only choices remaining are how to distribute the consequences and how to prepare for what comes next.

The second-order effects will unfold over decades. The apprenticeship collapse will manifest in the 2030s, when the generation that never learned the craft reaches seniority. The credential spiral will accelerate until something breaks—perhaps a return to demonstrated competence, perhaps a complete decoupling of credentials from employment. The sovereignty crises will intensify as compute becomes more strategic and water becomes more scarce. The temporal incommensurability will produce policy failures that seem inexplicable until the different timescales become visible.

None of this is inevitable in its specifics. All of it is probable in its general shape. The agents have entered the workforce. The second-order consequences have begun. The architecture is changing, whether we notice or not.