The Ice That Binds: Trump's Greenland Gambit and the Fractures in American Arctic Strategy

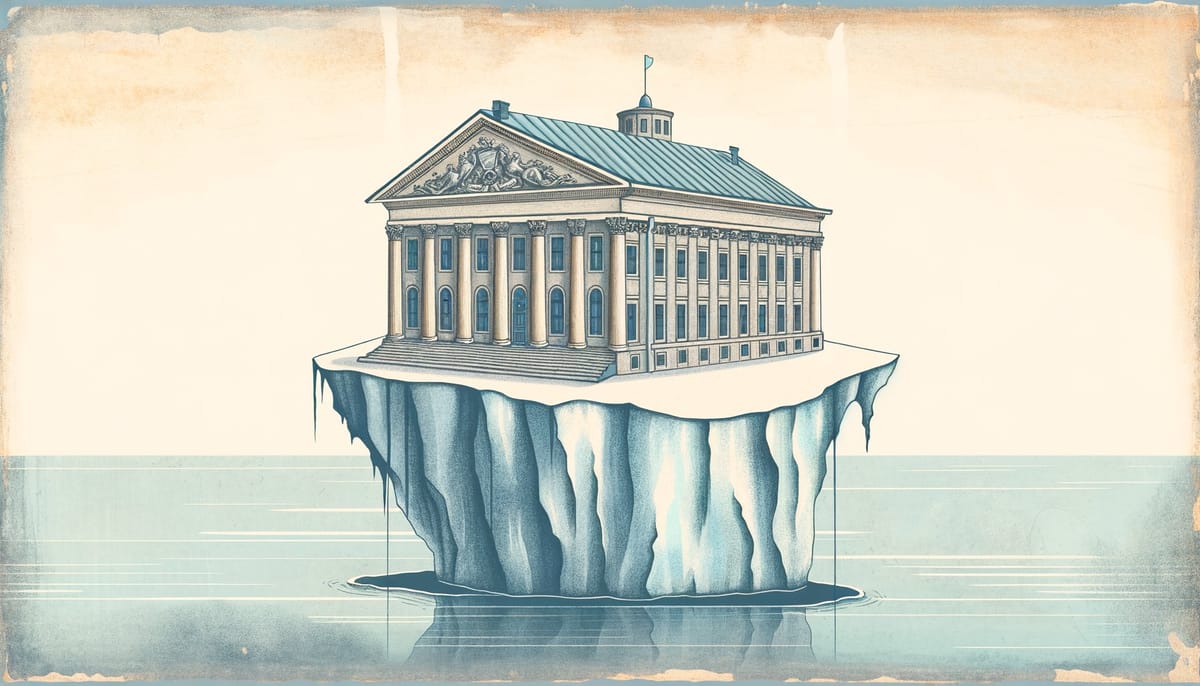

Trump's demand for Greenland ownership does not create contradictions in US Arctic strategy—it exposes structural fractures that have long empowered patient adversaries. The real question is whether Washington can align its planning horizons with melting realities.

The Ice That Binds

Donald Trump wants to buy Greenland. He has said so repeatedly since 2019, and since returning to office in 2025 he has escalated from aspiration to ultimatum. He refuses to rule out military force. He threatens Denmark with tariffs. He dispatches his son to Nuuk for reconnaissance. The island, he insists, is “an absolute necessity” for American security.

Set aside whether this will happen. The more revealing question is what the pursuit exposes. Trump’s Greenland gambit does not merely contradict American Arctic strategy. It illuminates contradictions that were already there—structural fractures in how Washington thinks about the high north that neither the 2022 National Strategy for the Arctic Region nor the Pentagon’s 2024 Arctic Strategy resolved. These fractures do not automatically empower Russia and China. But they create openings that patient adversaries know how to exploit.

The Arctic is warming faster than anywhere else on Earth. New shipping lanes are opening. Resources once locked under ice are becoming accessible. Great-power competition has arrived at latitudes where America has grown accustomed to operating without challenge. And Washington’s response has been to publish strategies that emphasise multilateral cooperation while its commander-in-chief threatens to seize allied territory.

That dissonance is not merely embarrassing. It is strategically consequential.

The Strategy That Wasn’t

The United States has Arctic strategies. What it lacks is Arctic coherence.

The Biden administration’s 2022 National Strategy for the Arctic Region established four pillars: security, climate and environmental protection, sustainable economic development, and international cooperation. The document acknowledged “increasing strategic competition, exacerbated by Russia’s unprovoked war in Ukraine and the People’s Republic of China’s escalating efforts to garner influence in the region.” It promised to work with allies and partners. It emphasised rules-based order.

The Pentagon’s 2024 Arctic Strategy built on this foundation, warning that “PRC and Russian activities in the Arctic—including their growing cooperation—the enlargement of NATO, and the increasing effects of climate change herald a new, more dynamic Arctic security environment.” The document called for enhanced capabilities, improved domain awareness, and strengthened alliances.

Then came Trump’s 2025 National Security Strategy. The Arctic receives no dedicated section. The omission is telling. Not because Trump ignores the region—his Greenland fixation proves otherwise—but because his approach cannot be reconciled with the strategic frameworks his own government inherited.

Consider the contradiction. American Arctic strategy since 2013 has emphasised that “the Arctic is not likely to be a source of conflict over territorial claims” under current international law. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea provides mechanisms for resolving overlapping continental shelf claims. The Arctic Council has fostered cooperation even among adversaries. Russia and the West maintained functional working relationships on Arctic matters long after relations collapsed elsewhere.

Trump’s approach inverts this logic. By publicly proposing to purchase Greenland—and refusing to rule out force—he signals that Arctic territory is negotiable, that sovereignty can be bought or taken, that the rules-based frameworks America championed are optional when American interests are at stake. This does not strengthen deterrence. It legitimises the very revisionism Washington claims to oppose.

The structural problem runs deeper than rhetorical inconsistency. American Arctic strategy has long suffered from what analysts call temporal incommensurability. Russia operates on generational timescales, its Arctic ambitions rooted in centuries of northern expansion and a strategic culture that treats the region as existentially Russian. China plans in decades, its Polar Silk Road initiative part of a patient infrastructure strategy that has already secured equity stakes in Russian Arctic energy projects. The United States plans in budget cycles.

This temporal mismatch creates predictable outcomes. The Coast Guard’s Polar Security Cutter programme has become a case study in bureaucratic momentum substituting for operational capability. The focus on “building up the program’s bureaucratic momentum” rather than delivering ships reveals that in protracted acquisition cycles, institutional survival mechanisms—budget justification, stakeholder management, process compliance—replace the urgent delivery of actual icebreakers. America has two operational heavy icebreakers. Russia has more than forty.

The Greenland Paradox

Greenland matters. On this point, Trump is not wrong.

The island sits astride the GIUK gap—the Greenland-Iceland-United Kingdom passage through which Russian submarines must transit to reach the Atlantic. Pituffik Space Base (formerly Thule) hosts critical early-warning radars and space surveillance systems. The island’s rare earth deposits could reduce Western dependence on Chinese processing. Its ice sheet, if it melts, will reshape global coastlines.

But the manner of American pursuit matters as much as the objective. Trump’s approach creates what might be called the Greenland paradox: the more aggressively America seeks control, the more it undermines the conditions that make control valuable.

Start with alliance cohesion. Greenland is Danish territory, covered by NATO’s Article 5 collective defence guarantee. When Trump threatens military action against a NATO ally to acquire its territory, he does not merely strain the alliance. He creates a legal absurdity. NATO’s November 2025 clarification that Article 5 assistance “may, but does not have to, include armed force” was designed for external threats. If America attacks Greenland and then blocks Article 5 military operations through its veto power, allies remain obligated to assist Denmark through non-kinetic means—while the attacker controls whether kinetic defence is permitted.

This is not hypothetical legal theorising. It is the logical endpoint of Trump’s stated position. And every NATO member understands it.

The damage to alliance credibility compounds through a mechanism that requires no American military action at all. Danish military intelligence has elevated the United States to threat assessment status for the first time in history. Meanwhile, Danish Foreign Minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen publicly declares “no foreign policy crisis” and calls American concerns “legitimate.” This split between public diplomatic normalisation and intelligence agency threat escalation reveals a government managing contradictory imperatives—maintaining alliance relationships while preparing for an ally that may become an adversary.

Greenland itself presents a different paradox. Trump’s crude acquisition rhetoric has inadvertently elevated Greenlandic constitutional actors in ways that complicate rather than facilitate American objectives. By forcing international recognition of Greenland as a geopolitical object of desire, the rhetoric creates diplomatic arbitrage opportunities. Greenland’s government can now extract concessions from multiple suitors. The March 2025 snap election, triggered partly by Trump’s pressure, brought to power a coalition even more committed to eventual independence.

Here is the irony: treating Greenland as tradable military real estate—like Puerto Rico in American strategic thinking—legitimises the very decolonisation logic that could remove it from NATO’s legal perimeter entirely. An independent Greenland would not automatically remain in the alliance. It would negotiate its own terms.

What Russia and China Actually Gain

Do these contradictions “empower” Russia and China? The answer is more nuanced than the question implies.

Russia benefits from American strategic incoherence, but not in the ways commonly assumed. Moscow’s Arctic position rests on physical presence, not diplomatic manoeuvre. The Northern Fleet dominates the region’s military balance. Russian icebreakers control the Northern Sea Route. Arctic bases have been reactivated and expanded. When American strategy documents prioritise China over Russia as the Arctic threat—as the 2024 Pentagon strategy does—they reveal what one analyst calls “psychological projection of U.S. imperial anxiety onto non-threatening actor.” China has no Arctic military presence. Russia has the world’s largest.

This misallocation of strategic attention serves Russian interests regardless of what happens in Greenland. Every American dollar spent preparing for a Chinese Arctic challenge that does not exist is a dollar not spent on capabilities that would actually constrain Russian operations.

But Russia’s gains have limits. The Northern Sea Route remains economically marginal despite climate-driven ice retreat. Permafrost thaw—the same warming that opens shipping lanes—is destroying the infrastructure that makes Arctic operations possible. Russian Arctic ports are sinking into softening ground. Pipelines are buckling. The economic substrate for Arctic development is dissolving beneath itself.

China’s position is more complex. Beijing declared itself a “near-Arctic state” in 2018—a geographic absurdity that nonetheless signals strategic intent. The Polar Silk Road integrates Arctic shipping into the Belt and Road Initiative. Chinese firms hold equity stakes in Russian Arctic energy projects, including 30% of Yamal LNG. This creates structural bypass of Russian transit fees: by becoming equity partners in cargo origin points rather than mere transit customers, Chinese firms convert the Northern Sea Route from toll road to company highway.

American strategic incoherence benefits China primarily through opportunity cost. Every month Washington spends debating Greenland acquisition is a month not spent building processing capacity for the rare earths that Greenland’s deposits might eventually yield. The United States mines approximately 11.5% of global rare earth production, but China controls over 90% of global processing capacity. Territorial control of deposits is meaningless without the industrial capacity to transform ore into usable materials. America could own every rare earth mine on Earth and still depend on China to make them useful.

The Greenland controversy also provides narrative ammunition. Chinese state media can frame American Arctic expansion as proof that Washington’s commitment to sovereignty and international law is selective at best. When the United States publishes extended continental shelf claims while remaining outside UNCLOS, it provides Russia rhetorical cover for its own departures from international norms. The rules-based order America champions becomes, in adversary framing, a rules-for-thee order that binds others while America does as it pleases.

The Infrastructure of Contradiction

Beneath the diplomatic theatre lies a more fundamental problem: America is building Arctic strategy on melting ground.

Military infrastructure operates on 30-50 year design timelines. The permafrost it sits on will fundamentally transform within a decade. This temporal mismatch creates what engineers call stranded assets—investments that become worthless before their intended lifespan expires. Alaska faces $5.5 billion in permafrost-related infrastructure damage by 2099, representing 38% of the state’s total climate costs. Roads are buckling. Runways are warping. The physical foundation of American Arctic presence is becoming unreliable.

This creates a strategic planning paradox. Investments made today assume conditions that will not exist when the investments mature. But delaying investment cedes the present to adversaries who are building regardless. Russia’s Arctic infrastructure is also degrading—but Russia is building anyway, accepting that some percentage of investment will be lost to thaw. America’s acquisition processes are too slow to match this risk tolerance.

The Pituffik Space Base illustrates the compound problem. Its radar domes face upward, tracking missiles and satellites. This orientation creates a geometric blindspot to the subsurface domain directly beneath its operational envelope. While Pituffik monitors orbital space, Russian GUGI (Main Directorate of Deep-Sea Research) units develop capabilities to target the undersea cables and infrastructure that American Arctic operations depend upon. The surveillance architecture watches the wrong domain.

Meanwhile, the 2014 transfer of Thule maintenance contracts from Greenlandic to American companies created economic grievances that transformed the Defence Agreement from security arrangement into contested economic constitution. Mundane procurement decisions accumulated into political legitimacy crises. The infrastructure of American presence generated the resentment that now complicates American presence.

What Would Actually Work

If American Arctic strategy is structurally contradictory, what would coherent strategy require?

First, temporal alignment. American planning horizons must extend beyond budget cycles. This is not a call for vague “long-term thinking” but for specific institutional reforms: multi-year acquisition authorities that survive administration changes, infrastructure investments designed for degradation rather than permanence, and diplomatic frameworks that outlast electoral cycles. Russia and China plan in decades. America must learn to do the same.

Second, capability before aspiration. The icebreaker gap is not a talking point. It is an operational constraint that limits everything else America can do in the Arctic. Two heavy icebreakers cannot sustain the presence that strategy documents promise. Building more requires accepting that some will be obsolete before completion—and building anyway. Perfect is the enemy of present.

Third, alliance repair. Trump’s Greenland approach has damaged relationships that took decades to build. Repairing them requires more than rhetorical reassurance. It requires demonstrating that American security guarantees are not contingent on American territorial ambitions. This may mean explicitly renouncing acquisition by force—a commitment that costs nothing if America never intended force anyway, and reveals much if America refuses to make it.

Fourth, processing before extraction. Greenland’s rare earths are worthless without the industrial capacity to refine them. China’s processing monopoly is the actual strategic vulnerability, not access to deposits. Building domestic processing capacity is harder than acquiring territory—and more valuable.

Fifth, indigenous engagement. Greenland’s population is 88% Inuit. Any sustainable American relationship with the island requires their consent, not merely Danish acquiescence. The Inuit Circumpolar Council and Greenland’s Self-Government institutions are not obstacles to American interests. They are the legitimate authorities whose cooperation makes American interests achievable.

Each of these requirements involves trade-offs. Temporal alignment means accepting that some investments will fail. Capability building means spending money on assets that may become stranded. Alliance repair means constraining American freedom of action. Processing investment means competing with Chinese industrial policy. Indigenous engagement means accepting that Greenlanders may say no.

The alternative—continuing current contradictions—has its own costs. They are just distributed differently, falling on future administrations, depleted alliances, and strategic positions ceded by default.

The Quiet Fracture

Trump’s Greenland push did not create American Arctic contradictions. It exposed them.

The gap between strategy documents and operational reality predates this administration. The mismatch between multilateral rhetoric and unilateral instincts has characterised American Arctic policy for years. The temporal incommensurability between American planning cycles and adversary patience is structural, not personal.

What Trump added was visibility. By stating openly what previous administrations implied quietly—that American interests trump alliance commitments when the stakes are high enough—he forced allies and adversaries alike to update their assessments. Denmark now plans for American threats. China now cites American behaviour to justify its own. Russia now watches as America demonstrates that sovereignty is negotiable for the powerful.

The Arctic is warming. The ice is retreating. New passages are opening. Great powers are positioning for advantage. In this competition, coherent strategy beats contradictory strategy. Patient strategy beats impulsive strategy. Present capability beats promised capability.

America has strategies. What it needs is the capacity to execute them without undermining them in the process.

The ice does not care about American contradictions. It melts regardless. The question is whether American strategy can adapt faster than the ground shifts beneath it.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Could the US actually use military force to take Greenland? A: Legally, any use of force against Greenland would trigger NATO Article 5, as the island is Danish territory. Practically, the US has overwhelming military superiority in the region, but the alliance and diplomatic costs would far exceed any strategic benefit from the territory itself.

Q: Why does Greenland matter strategically? A: Greenland’s location astride the GIUK gap makes it critical for monitoring Russian submarine movements into the Atlantic. Pituffik Space Base hosts early-warning radars essential for missile defence. The island also contains significant rare earth deposits, though these remain largely undeveloped.

Q: Is China really an Arctic power? A: China declared itself a “near-Arctic state” in 2018, but this is aspirational rather than geographic. China has no Arctic coastline, limited icebreaking capability, and no permanent military presence in the region. Its Arctic influence comes through investment in Russian energy projects and scientific research stations, not territorial presence.

Q: What would Greenland independence mean for US interests? A: An independent Greenland would not automatically remain in NATO or maintain existing US basing agreements. It would negotiate new arrangements on its own terms, potentially playing American, European, and Chinese interests against each other. This could either enhance or diminish US access depending on how Washington manages the relationship.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- National Strategy for the Arctic Region (2022) - Biden administration’s framework establishing four strategic pillars for Arctic engagement

- Department of Defense Arctic Strategy (2024) - Pentagon assessment of Russia-China cooperation and Arctic security environment

- Rare Earth Processing 2025: Global Capacity and Key Players - Analysis of China’s dominance in rare earth processing infrastructure

- The Intersection of US Military Infrastructure and Alaskan Permafrost - Arctic Institute assessment of climate impacts on defence installations

- Russia’s Territorial Claims, UNCLOS, and the Lomonosov Ridge - Analysis of Russian continental shelf claims under international law

- Chinese Investments in Greenland Raise US Concerns - Danish Institute for International Studies examination of strategic investment patterns

- China’s Arctic Policy White Paper - Official Chinese government statement establishing “near-Arctic state” doctrine

- At the Intersection of Arctic Indigenous Governance and Extractive Industries - Academic analysis of indigenous rights frameworks in Arctic resource development