The Ice Beneath the Peace

Antarctica's greatest asset is its legal fiction. For sixty-five years, the Antarctic Treaty System has performed an extraordinary conjuring trick: seven nations claim sovereignty over the continent, two superpowers reserve the right to claim, and everyone pretends that freezing these positions...

The story is breaking down. What was designed as a Cold War pressure valve has become a theatre for a different kind of competition, one that operates not through territorial assertion but through infrastructure accumulation, scientific positioning, and the patient exploitation of consensus rules designed for a vanished era. China and Russia are not challenging the Antarctic Treaty. They are hollowing it out from within.

The Architecture of Ambiguity

The Treaty’s genius was also its vulnerability. By freezing sovereignty claims rather than resolving them, the original negotiators created a system that could accommodate irreconcilable positions—but only so long as no party pushed too hard. The mechanism assumed rough parity among participants and shared interest in avoiding conflict. Neither assumption holds today.

Consider the numbers. In 1959, twelve nations signed the Treaty. Today, fifty-four are parties, but only twenty-nine hold consultative status with voting rights. The barrier to entry is instructive: “substantial scientific research activity” in Antarctica. This sounds meritocratic. It functions as a wealth test. Building and maintaining Antarctic stations requires icebreaker fleets, long-range aircraft, cold-weather logistics chains, and billions in sustained investment. The criterion screens for industrial and military capacity disguised as scientific commitment.

China understood this immediately. Its first Antarctic station opened in 1985. It now operates five, with a sixth under construction. The progression tells a strategic story: Great Wall Station (1985) on King George Island established presence; Zhongshan (1989) accessed the ice sheet interior; Kunlun (2009) reached Dome A, the highest point on the Antarctic plateau and prime territory for astronomical observation; Taishan (2014) created a logistics node; and the planned new station will expand this network further. Each facility is positioned not merely for science but for comprehensive continental coverage.

Russia’s approach differs in method but not in intent. Its eight stations—inherited from Soviet ambition—occupy positions that maximise geographic spread and strategic access. Vostok Station sits atop a subglacial lake containing water isolated for fifteen million years. Progress Station anchors logistics for the Australian-claimed sector. Bellingshausen Station on King George Island monitors the Antarctic Peninsula chokepoint. The infrastructure predates the current competition but serves it perfectly.

The United States maintains three stations, including McMurdo, the continent’s largest settlement with summer populations exceeding 1,000. American presence remains substantial. But here is the asymmetry that matters: while Washington debates icebreaker funding in congressional appropriations cycles, Beijing executes a polar strategy spanning decades. America’s two operational heavy icebreakers face a Chinese fleet of five, with more under construction. Russia commands over forty.

This is not a resource problem. It is an activation problem.

The Consensus Weapon

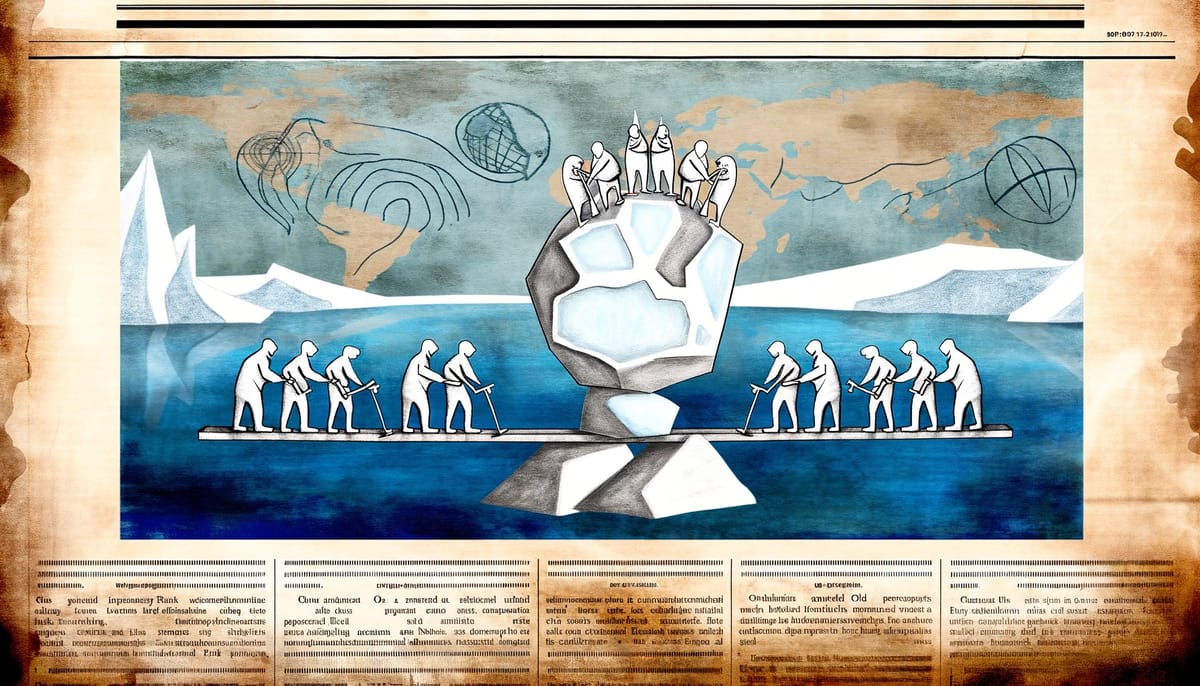

The Antarctic Treaty System operates by consensus. No measure passes without unanimous agreement among consultative parties. This was meant to protect minority interests and ensure buy-in. It has become a veto mechanism for states wishing to prevent action while avoiding the appearance of obstruction.

The Ross Sea Marine Protected Area negotiations reveal the pattern with uncomfortable clarity. From 2011 to 2016, China and Russia blocked the proposal through procedural objections, scientific queries, and requests for additional study. The MPA eventually passed—but only after its protected area shrank by two-thirds and its duration was limited to thirty-five years. The consensus requirement transformed time into a negotiating asset. Each year of delay extracted territorial concessions. The blocking parties didn’t oppose protection; they extracted maximum spatial reduction through strategic patience.

CCAMLR, the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, faces the same dynamic. Proposals for new marine protected areas in East Antarctica and the Weddell Sea have stalled for years. China’s fishing fleet operates extensively in Antarctic waters, harvesting krill at industrial scale. Russia’s interests align. Neither nation needs to reject conservation outright. They need only demand more data, question methodologies, and propose alternative boundaries—indefinitely.

The procedural elegance is remarkable. Consensus rules designed to ensure cooperation now guarantee paralysis. The system’s defenders call this resilience. A more accurate term might be ossification.

Dual-Use by Design

Every Antarctic research station is a dual-use facility. This is not conspiracy; it is physics. The same satellite ground stations that relay climate data can track missile trajectories. The same runways that land scientific cargo planes can accommodate military transports. The same ice-penetrating radar that maps subglacial geology can characterise terrain for purposes unrelated to science.

The C-17 Globemaster, the workhorse of American Antarctic logistics, requires runways of at least 1,064 metres. Any Antarctic runway exceeding this threshold becomes militarily viable while remaining legally defensible as scientific infrastructure. China’s planned facilities and Russia’s existing ones meet this standard. The Treaty prohibits military bases, military manoeuvres, and weapons testing. It does not prohibit infrastructure that could serve military purposes if circumstances changed.

Satellite ground stations present the cleaner case. Polar orbits pass over Earth’s poles on every revolution—a satellite in polar orbit must communicate with high-latitude ground stations to maintain continuous coverage. Antarctic facilities aren’t conveniences; they are necessities for comprehensive satellite networks. China’s Zhongshan Station hosts ground equipment for its BeiDou navigation system. The scientific justification is genuine. So is the strategic value.

Automated monitoring infrastructure compounds the ambiguity. Weather stations, GPS reference points, and seismographs operate year-round without human presence. They collect environmental data. They also enable persistent surveillance of a kind that episodic seasonal research cannot match. The normalisation of remote sensing creates legitimate cover for capabilities that serve multiple masters.

The Treaty’s framers could not have anticipated this convergence. They wrote rules for a world where military and scientific activities were distinguishable. That world has passed.

The Resource Shadow

The Madrid Protocol of 1991 banned mineral resource activities in Antarctica for fifty years. The prohibition holds until 2048, when it becomes subject to review. This date has acquired mythological status—the moment when the scramble for Antarctic resources supposedly begins.

The myth obscures more than it reveals. The Protocol can only be modified by consensus among consultative parties, plus ratification by three-quarters of them. The legal barriers to lifting the mining ban are formidable. But the myth’s power lies not in its accuracy but in its effect on present behaviour.

States are positioning for a future they publicly disavow. China’s station network provides comprehensive access to regions of potential mineral interest. Russia maintains presence in sectors where geological surveys hint at hydrocarbon deposits. The scientific research exemption in the Madrid Protocol permits geological investigation—and the knowledge gathered now will inform decisions later.

Krill fisheries offer a more immediate arena. Antarctic krill constitute the largest animal biomass on Earth, the foundation of the Southern Ocean food web, and an increasingly valuable commodity for aquaculture feed and omega-3 supplements. China’s krill catch has grown dramatically. Russian vessels operate alongside. CCAMLR sets catch limits, but enforcement depends on flag-state compliance, and the monitoring regime has gaps that sophisticated operators can exploit.

The krill story contains a hidden dimension. Krill faecal pellets sink rapidly, transporting carbon from surface waters to the deep ocean. By regulating krill harvests to protect predator populations, CCAMLR inadvertently functions as a carbon sequestration regime. The fishing quotas are climate policy by accident. No one designed this. No one governs it coherently.

Genetic resources occupy a different regulatory void. The Madrid Protocol addressed minerals because minerals were the concern of 1991. Biological prospecting—sampling extremophile organisms for pharmaceutical or industrial applications—remained unregulated. The Nagoya Protocol on genetic resources explicitly excludes areas beyond national jurisdiction. Antarctic genetic material exists in a legal vacuum that commercial interests are already exploring.

The Claimant Dilemma

Seven nations assert territorial claims in Antarctica: Argentina, Chile, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, France, and Norway. Three claims overlap on the Antarctic Peninsula—Argentine, Chilean, and British—creating a frozen conflict that the Treaty system manages rather than resolves.

These claimant states face an impossible position. They must maintain their claims through continuous presence and activity while operating within a Treaty system that neither recognises nor extinguishes those claims. Every station they build, every flag they plant, every birth certificate they issue for children born on Antarctic territory serves dual purposes: scientific cooperation and sovereignty performance.

Argentina and Chile have gone furthest. Both maintain year-round settlements with families, schools, and civil infrastructure. Argentina’s Esperanza Base has hosted births since 1978—a deliberate effort to establish multigenerational presence. Chile’s Villa Las Estrellas includes a school, hospital, and bank. These are not research stations. They are colonial outposts in scientific disguise.

The United Kingdom’s position is more constrained but no less strategic. British Antarctic Territory overlaps entirely with Argentine and Chilean claims. The Falklands War of 1982 demonstrated that South Atlantic sovereignty disputes can turn violent. British presence in Antarctica serves as insurance against future challenges—and as a reminder that London takes its claims seriously.

Australia claims the largest Antarctic territory: 42% of the continent. Its capacity to monitor and maintain presence across this vast area is limited. China’s expanding station network operates partly within the Australian claim. Canberra watches with growing unease but limited options. Objecting too loudly risks destabilising the Treaty system that legitimises Australian presence. Staying silent risks normalising Chinese infrastructure in territory Australia considers its own.

The claimant states are trapped. They cannot abandon their claims without domestic political cost. They cannot assert them without threatening the cooperative framework that enables their presence. They perform sovereignty while pretending not to.

The Governance Gap

Antarctica’s governance architecture was built for twelve nations sharing a frozen wilderness. It now struggles with fifty-four parties, 74,000 annual tourists, and commercial interests the original negotiators never imagined.

Tourism illustrates the strain. The International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators (IAATO) self-regulates the industry with considerable success. Operators coordinate landing schedules, enforce environmental protocols, and maintain safety standards. This works because IAATO members have commercial incentives to preserve Antarctica’s pristine appeal.

But self-regulation creates perverse dynamics. States have avoided developing their own regulatory capacity because the private sector solution appears adequate. IAATO’s effectiveness prevents the emergence of state-based governance that could address operators outside the association or activities beyond its mandate. Success breeds dependency, and dependency breeds vulnerability.

Environmental impact assessment requirements assume state capacity to review activities before they occur. The volume of tourism operations—hundreds of landings per season—makes meaningful prior review impossible. Formal governance exists. Functional governance does not.

Climate change accelerates every pressure. Sea ice extent has declined dramatically. Access windows are lengthening. Ecosystems are shifting. Invasive species that could not survive Antarctic conditions a generation ago now threaten to establish themselves. The governance system responds slowly because consensus requires agreement, and agreement requires compromise, and compromise requires time that the physical environment no longer provides.

The temporal mismatch is structural. Ecological regime shifts occur over years to decades. Ice sheet dynamics play out over centuries to millennia. Governance operates on electoral cycles measured in quarters. Each system runs on its own clock. None synchronises with the others.

What Breaks First

The Antarctic Treaty System will not collapse dramatically. It will erode incrementally, its norms hollowed out while its forms persist. The question is not whether competition intensifies but how it manifests.

Three scenarios deserve attention. In the first, consensus paralysis continues until the system becomes purely ceremonial—a venue for diplomatic performance while actual competition occurs through infrastructure, presence, and fait accompli. This is the default trajectory. It requires no decisions, only drift.

In the second, a crisis forces clarity. A confrontation over fishing rights, a sovereignty dispute that escalates, an environmental disaster requiring coordinated response—any of these could reveal the gap between the Treaty’s formal authority and its practical capacity. Crises select which function of dual-use infrastructure becomes visible. A search-and-rescue emergency reveals logistics capability. A sovereignty challenge reveals military potential.

In the third, external pressure reshapes the system. Great power competition elsewhere—in the South China Sea, the Arctic, or beyond—spills into Antarctic diplomacy. The continent becomes a bargaining chip in negotiations about things that matter more to the principals. This is how Antarctica entered the international system in 1959, as a Cold War pressure release. It could exit the same way.

The United States faces a choice it has not clearly made. American Antarctic presence remains substantial but static. Chinese and Russian presence is expanding. The gap widens annually. Closing it would require sustained investment over decades—icebreakers, stations, logistics infrastructure, scientific programmes. Washington’s attention is elsewhere. Beijing’s is not.

Australia confronts a sharper version of the same dilemma. Its claimed territory hosts growing Chinese infrastructure. Its alliance with the United States creates expectations it may not be able to meet. Its geographic proximity makes Antarctic developments strategically significant in ways they are not for more distant powers. Canberra has begun to respond—new icebreaker procurement, increased Antarctic funding, diplomatic engagement with like-minded states. Whether this suffices remains uncertain.

The Uncomfortable Truth

Antarctica’s future will be determined by states that plan in decades competing with states that plan in electoral cycles. The Treaty system’s survival depends on consensus among parties whose interests increasingly diverge. The infrastructure being built today will shape options available tomorrow.

The comfortable narrative—that Antarctica remains a continent dedicated to peace and science, protected by international cooperation—is not false. It is incomplete. Beneath the cooperation runs competition. Within the science operates strategy. Behind the consensus lurks the veto.

This is not cause for despair. The Antarctic Treaty System has survived challenges before. It may adapt again. But adaptation requires recognition that the system designed for 1959 cannot govern 2025 unchanged. The frozen sovereignty of Article IV was a solution to one era’s problem. It has become the next era’s vulnerability.

Antarctica will not be fought over with armies. It will be contested through stations and icebreakers, through scientific programmes and fishing fleets, through the patient accumulation of presence that creates facts on the ground—or rather, on the ice. The competition is already underway. The only question is whether those who value the Treaty system’s achievements will compete effectively to preserve them, or watch as others reshape the continent’s future through the simple expedient of showing up.

The ice does not care about treaties. It responds to physics. The same might be said of geopolitics.