The Geography of Fear

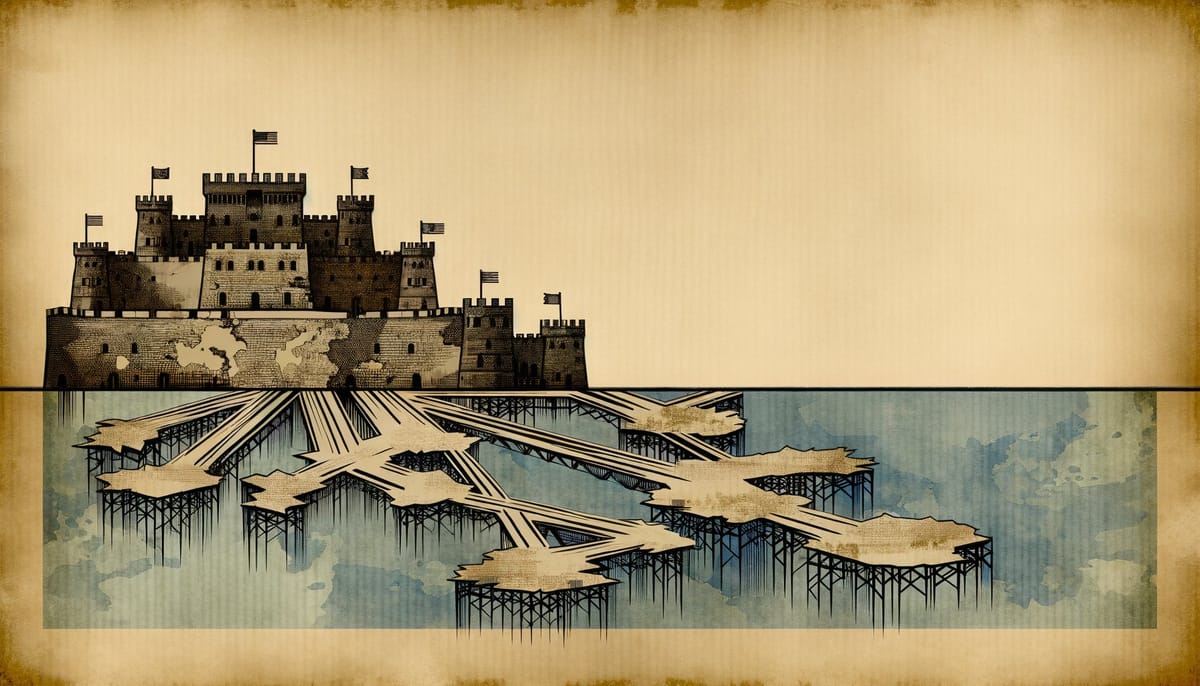

America's military infrastructure is migrating eastward and fragmenting as it goes. The redistribution of bases and decentralization of command reveal what doctrine papers obscure: the United States has accepted that its dominance can no longer be assumed, only contested.

The Geography of Fear

The Pentagon’s maps tell a story its briefings cannot admit. In 2012, the United States maintained 598 military installations abroad, concentrated in the arc from Germany through the Persian Gulf to South Korea—the architecture of a superpower fighting yesterday’s wars. By 2024, that number had dropped to 514, but the reduction masks a transformation more significant than contraction. Bases in Europe shrank while facilities across the Pacific proliferated. Commands that once operated from fixed headquarters now disperse across dozens of smaller sites. The concrete and steel of American military power is migrating eastward, fragmenting as it goes.

This is not merely strategic adjustment. It is confession. The geographic redistribution of defense infrastructure reveals what doctrine papers obscure: the United States has accepted that its military dominance can no longer be assumed, only contested. And the decentralization of command structures—once heresy in an institution that worshipped unity of command—acknowledges something more troubling still. The next war will be fought in an environment where communication fails, where headquarters burn, where the officer on the ground must act without orders from above.

The concrete is moving because the fear has changed.

From Fortress to Archipelago

The Cold War bequeathed America a military posture built for mass. Enormous bases in Germany, Japan, and South Korea served as staging grounds for wars that never came—or came elsewhere. Ramstein Air Base sprawled across 3,000 acres. Camp Humphreys in South Korea became the largest overseas American installation, housing 36,000 personnel. These were not forward positions but permanent cities, their size a statement: we are here to stay.

The logic was coherent for its era. Fixed infrastructure enabled power projection. Large bases provided economies of scale. Concentrated forces could mass quickly. The assumption underneath: American forces would deploy from sanctuary to battlefield, not fight where they lived.

China’s missile program demolished that assumption. The People’s Liberation Army now fields over 2,000 ballistic and cruise missiles capable of reaching American bases across the Western Pacific. The DF-26, with its 4,000-kilometer range, can strike Guam. Shorter-range systems hold Japan’s bases at risk. The Pentagon’s own assessments conclude that in the opening hours of a Taiwan conflict, fixed installations in the region would face saturation attacks.

The response has been architectural. The Marine Corps’ Force Design 2030 eliminates tanks entirely and restructures around small, dispersed units designed to operate from temporary positions across Pacific islands. The Army’s Multi-Domain Task Forces—new formations created specifically for the Indo-Pacific—are built to fight distributed, accepting that concentration means annihilation. The Air Force’s Agile Combat Employment concept assumes main operating bases will be destroyed and plans accordingly: smaller teams, austere airfields, rapid relocation.

This is not evolution. It is inversion. For decades, American military doctrine sought to concentrate force at decisive points. Now it seeks to avoid presenting targets worth hitting.

The numbers tell the story. Between 2018 and 2024, the United States negotiated access agreements for new facilities in Palau, Papua New Guinea, and the Philippines. The Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement with Manila expanded American access from five to nine sites. Guam, once considered the Pacific’s Gibraltar, is being supplemented by a constellation of smaller positions across Micronesia—not because Guam is being abandoned, but because relying on it alone has become suicidal.

The Command Paradox

Goldwater-Nichols was supposed to solve military dysfunction. The 1986 legislation, passed after the Desert One debacle and Grenada’s chaos, established clear chains of command running from the President through the Secretary of Defense to unified combatant commanders. It worked brilliantly for the wars America chose to fight: Kuwait, Kosovo, Afghanistan, Iraq. A single commander owned the battlespace. Information flowed upward. Orders flowed down.

The system assumed one thing that no longer holds: that communications would function.

Modern warfare has become a contest of electromagnetic annihilation. Russian forces in Ukraine demonstrated sophisticated electronic warfare capabilities that severed Ukrainian units from their headquarters for hours at a time. Chinese doctrine explicitly targets command and control networks. American war games consistently reveal that in a high-intensity conflict, the satellite links and fiber-optic cables connecting commanders to forces would be among the first casualties.

The Pentagon’s response is JADC2—Joint All-Domain Command and Control—an initiative to create redundant, resilient networks that can survive attack. But technology alone cannot solve a doctrinal problem. If the network fails, who decides?

The answer emerging from doctrine and exercises is: everyone. Mission command—the philosophy of providing subordinates with intent rather than detailed orders—has migrated from Army field manuals to become the organizing principle of American military thought. Commanders at every echelon are being trained to act independently when communications fail. The 2022 National Defense Strategy explicitly calls for “decision-making at the tactical edge.”

This represents a profound cultural shift. The American military spent decades building systems that centralized information and decision-making. Generals in Tampa watched drone feeds from Afghanistan. Commanders in Qatar approved strikes in Syria. The assumption was that more information, processed at higher levels, produced better decisions.

That assumption is being abandoned—not because it was wrong, but because it was fragile. A military that cannot function without its headquarters is a military that can be decapitated.

The Space Force offers the clearest example of the new architecture. Established in 2019, it rejected the geographic combatant command model entirely. Space operations are inherently global; a satellite doesn’t care about CENTCOM’s boundaries. The service’s organizational structure emphasizes distributed operations, with units designed to function even if Space Operations Command in Colorado Springs goes dark.

NATO has followed a parallel path. After 2014, the alliance created Joint Force Command Norfolk and Joint Support and Enabling Command in Ulm—new headquarters that distribute authority previously concentrated in a handful of locations. The 2022 NATO Force Model restructured the alliance’s force posture around rapid deployment and distributed operations. These are not merely organizational charts. They are admissions that the next war will not wait for Brussels to convene.

The Domestic Calculus

Strategic logic explains where bases should go. Domestic politics determines where they actually go.

The Base Realignment and Closure process—BRAC—was designed to impose rationality on military infrastructure. Independent commissions would recommend closures; Congress would vote up or down on the entire package, preventing members from protecting individual installations. The system worked, after a fashion. Five BRAC rounds between 1988 and 2005 closed 350 installations and saved billions.

Then it stopped. Congress has not authorized a BRAC round since 2005. Every subsequent request from the Pentagon has been rejected. The reason is not strategic; it is electoral. Military bases anchor local economies. Closing them costs jobs and votes. The congressional delegation that permits a base closure in its district faces punishment at the polls.

The result is infrastructure frozen in amber. The Pentagon maintains installations it does not need while lacking facilities where it does. A 2016 study found 22% excess capacity in military infrastructure—buildings, hangars, and facilities that serve no operational purpose but cannot be closed because Congress refuses to authorize the process.

This is not merely inefficiency. It is strategic distortion. Resources spent maintaining obsolete bases in politically favored locations are resources not spent building distributed facilities in the Pacific. The geographic redistribution of military infrastructure is constrained not by strategic logic but by the electoral map.

Defense contractors compound the dynamic. The five largest defense companies—Lockheed Martin, RTX, Northrop Grumman, Boeing, and General Dynamics—distribute their supply chains across as many congressional districts as possible. The F-35 program involves suppliers in 46 states. This is not accident; it is strategy. A program with suppliers in 46 states has 92 senators with reasons to protect it.

The geographic concentration of defense industry employment shapes infrastructure decisions. The Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex hosts the largest concentration of defense workers in the nation. San Diego’s economy depends on naval facilities. These regions wield disproportionate influence over defense policy—and they use it.

The 2024 National Defense Authorization Act increased domestic content requirements for defense procurement to 75% by 2029. The stated rationale was supply chain resilience. The practical effect is to entrench existing geographic distributions of defense industry employment. Bases and production facilities reinforce each other: installations create demand for nearby suppliers; suppliers create constituencies that protect nearby installations.

Strategic priorities and domestic political economy are not merely in tension. They operate on different logics entirely. The Pacific demands dispersion; politics demands concentration. The result is a military posture shaped as much by the location of swing districts as by the location of adversary missiles.

The Climate Complication

Rising seas do not respect strategic plans.

The Department of Defense identified 1,700 installations vulnerable to climate effects. Tyndall Air Force Base in Florida was devastated by Hurricane Michael in 2018—$5 billion in damage, years of reconstruction. Norfolk Naval Station, the world’s largest naval base, experiences flooding with increasing frequency; projections suggest 270 or more flood events annually by 2050. Diego Garcia, the critical Indian Ocean logistics hub, sits barely two meters above sea level.

Climate vulnerability creates pressure for geographic redistribution that aligns poorly with strategic requirements. The Pacific islands most useful for distributed operations are also among the most exposed to sea-level rise and intensifying storms. Guam faces both Chinese missiles and typhoons. The infrastructure investments required for climate resilience compete with investments required for operational dispersion.

The Pentagon’s response has been adaptation rather than relocation. Installation resilience programs harden existing facilities against climate effects. But hardening has limits. Some locations will become untenable regardless of investment. The question is whether strategic necessity or climate reality will force the decision first.

Inland facilities gain attractiveness by default. The Army’s expansion of training ranges in the American Southwest reflects both the availability of space and the relative absence of climate exposure. But the Southwest cannot host naval facilities, and naval power remains central to Pacific strategy. The geography of climate risk and the geography of strategic competition do not align.

What the Concrete Reveals

Infrastructure decisions are strategy made permanent. A base takes years to build and decades to close. The facilities constructed today will shape military options in 2050. What does the current trajectory reveal about American strategic assumptions?

First, that great-power competition has displaced counterterrorism as the organizing principle of military posture. The Middle East footprint is contracting; the Pacific footprint is expanding. This is not merely rhetorical. It is concrete and steel.

Second, that survivability has displaced efficiency as the primary criterion for infrastructure decisions. Distributed facilities cost more to operate than concentrated ones. The Pentagon is accepting that cost because concentration has become synonymous with vulnerability.

Third, that the assumption of American technological superiority is eroding. The dispersal of forces and decentralization of command are adaptations to an adversary capable of contesting American dominance in every domain. A military confident in its ability to control the electromagnetic spectrum would not be training officers to fight without communications.

Fourth, that domestic political constraints will prevent optimal strategic adaptation. The infrastructure the Pacific requires will not be built as quickly as strategy demands because Congress will not close the bases that strategy no longer needs. The gap between strategic requirements and political feasibility is measured in years and billions of dollars.

The trajectory, absent intervention, leads to a military posture adequate for neither the wars America might fight nor the politics America cannot escape. Too concentrated for survival, too distributed for efficiency, constrained by congressional geography and climate physics alike.

The Interventions That Matter

Three leverage points exist. Each requires trade-offs that American politics has historically refused.

The first is BRAC authorization. Without the ability to close obsolete installations, the Pentagon cannot reallocate resources to strategic priorities. But BRAC authorization requires Congress to accept political pain—closed bases, lost jobs, angry constituents—for strategic gain that accrues to the nation rather than individual districts. The last successful BRAC round, in 2005, occurred under unified Republican government with a president at the height of wartime authority. Those conditions do not currently obtain.

The second is allied burden-sharing that goes beyond rhetoric. Distributed operations in the Pacific require host-nation facilities that the United States does not own and cannot build unilaterally. Japan’s decision to double defense spending and develop counterstrike capabilities represents genuine strategic alignment. Australia’s AUKUS commitment signals similar intent. But translating spending commitments into operational infrastructure requires years of construction and decades of political consistency. American strategy depends on allied governments that have not yet been elected.

The third is doctrinal commitment to decentralized command. The technology exists; the training programs exist; the doctrine exists. What does not yet exist is demonstrated willingness to accept the consequences. Decentralized command means junior officers making decisions that previously required general-officer approval. It means accepting outcomes that centralized control might have prevented. It means trusting the institution more than the individual commander. The American military has not been tested on this proposition since the early days of the Iraq insurgency—and the lessons of that period cut in multiple directions.

The Shape of What Comes

The maps will continue to change. Pacific facilities will multiply while European and Middle Eastern footprints contract. Commands will distribute authority downward even as they build redundant networks upward. Climate will force relocations that strategy would not have chosen. Congress will protect bases that serve electoral rather than operational purposes.

None of this is hidden. The National Defense Strategy says it plainly. The budget requests show it clearly. The concrete going into the ground across Micronesia and the Philippines makes it physical.

What remains uncertain is whether the adaptation will prove sufficient. The infrastructure being built today assumes a conflict that remains hypothetical. The command structures being reformed assume communications failures that have not yet occurred at scale. The distributed posture being adopted assumes allied cooperation that politics could revoke.

The geography of American military power is shifting because the geography of American fear has shifted. For three decades after the Cold War, the United States feared chaos in peripheral regions—failed states, terrorist sanctuaries, humanitarian catastrophes. It built a military posture for intervention: expeditionary, concentrated, projecting power from sanctuary to crisis.

Now it fears something older: a peer adversary capable of contesting American power in its own neighborhood. The posture required is different—distributed, survivable, capable of fighting hurt. The transition is underway. Whether it will be complete before it is tested remains the question that no amount of concrete can answer.

The bases are moving. The commands are fragmenting. The doctrine is evolving. And somewhere in the Taiwan Strait, the clock is running.