The Fence That Feeds the Fire

Donald Trump has inherited the most ambitious technology containment regime since the Cold War and vowed to make it stronger. The controls are working—just not in the ways Washington intended. As export restrictions multiply, they are reshaping the US-China competition in ways that may...

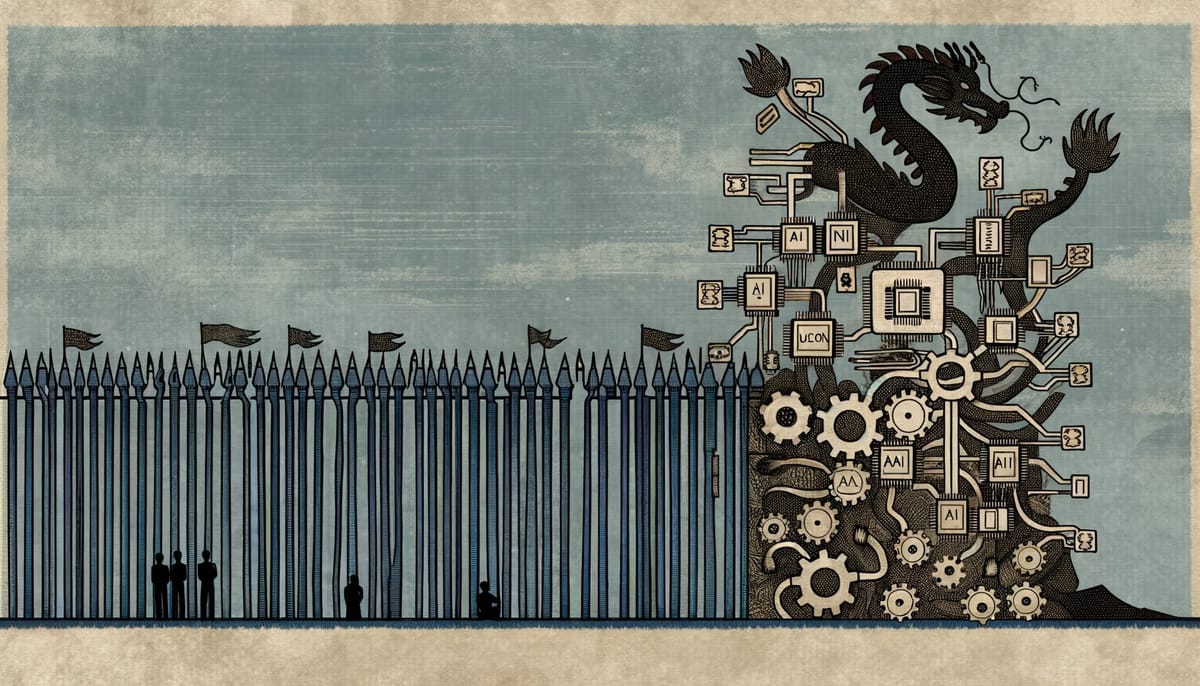

The Paradox of the Fence

The most consequential technology policy in a generation operates on a simple principle: build the fence high enough, and China cannot climb over. The Trump administration has inherited this logic from its predecessor, amplified the rhetoric, and confronted an awkward truth. The fence itself is becoming the problem.

When Donald Trump returned to the White House in January 2025, he brought with him a conviction that export controls on semiconductors and artificial intelligence represented one of the few Biden-era policies worth preserving—even expanding. Within weeks, his administration had withdrawn from multilateral technology agreements, threatened secondary sanctions on allied firms, and declared that any company facilitating Chinese AI development would face “the full force of American economic power.” The message was clear. The implementation was chaos.

What emerges from this chaos is not the story of American technological dominance reasserted. It is the story of a control regime that has begun to consume itself—where the act of building restrictions generates the very capabilities it seeks to deny, where allies become adversaries in the enforcement apparatus, and where the measurement of success has become structurally impossible. The Trump administration has not reshaped the technology competition with China. It has accelerated a transformation that was already underway, one that neither Washington nor Beijing fully controls.

The Architecture of Control

The export control regime that Trump inherited was already the most ambitious attempt at technological containment since the Cold War. The October 2022 rules, expanded in October 2023 and again in December 2024, targeted not just finished chips but the equipment to make them, the software to design them, and the expertise to operate the machinery. The logic was elegant: deny China access to the most advanced semiconductors, and you deny them the computational substrate for cutting-edge artificial intelligence.

The elegance concealed a structural flaw. Export controls function through classification—bureaucrats must decide which technologies fall under restriction and which do not. This creates what legal scholars call “bright-line thresholds,” and bright lines invite circumvention. The 50% ownership rule for affiliates, designed to prevent American technology from flowing through foreign subsidiaries, transformed the 49% ownership zone from unremarkable to strategically valuable overnight. Chinese firms restructured. Shell companies proliferated. The fence created the map for going around it.

Trump’s response has been to build higher. His administration added 80 Chinese entities to the Entity List in its first hundred days, expanded the definition of “U.S.-origin technology” to capture more foreign-made products, and threatened to impose secondary sanctions on any company, anywhere, that facilitated Chinese access to controlled items. The logic remained the same. The contradictions multiplied.

Consider the temporal mismatch at the heart of the regime. Semiconductor technology evolved through two centuries of cumulative scientific advancement—from Faraday’s electromagnetic discoveries in the 1820s to today’s 3-nanometer transistors. Each process node takes two to three years to stabilize. The Trump administration operates on a four-year electoral cycle, with policy announcements measured in news cycles and enforcement measured in quarterly results. The technology moves in decades. The policy moves in days.

This creates what one trade compliance officer described as “regulatory whiplash”—companies cannot plan investments when the rules change faster than the planning horizon. Forty percent of export licenses now face processing delays so severe that the uncertainty itself functions as a restriction. China has learned to weaponize the same tactic in reverse, deliberately slowing rare earth export permits to create sustained paralysis rather than outright bans.

The Allies’ Dilemma

The Trump administration’s most significant departure from its predecessor lies not in the substance of controls but in the mechanism of enforcement. Biden built coalitions. Trump issues ultimatums.

The results have been instructive. When the United States pressured the Netherlands to restrict ASML’s exports of advanced lithography equipment, the Dutch government initially complied—then began reframing the restrictions as matters of “national safety” rather than American coercion. The policy text remained identical. The political meaning transformed entirely. Like a Noh mask that appears to change expression through angle and lighting despite fixed carving, the Dutch restrictions now serve domestic political purposes that have little to do with American strategic objectives.

Japan presents a different pattern. Tokyo has maintained closer alignment with Washington on semiconductor controls, but Japanese firms have begun routing investments through Southeast Asian subsidiaries that fall outside the most restrictive classifications. Vietnam, explicitly positioning itself as “not China,” has discovered that its infrastructure gaps—unreliable power, workforce deficits, minimal existing capacity—have become strategic assets. The country’s incompleteness is the point. It offers American firms a compliance-friendly destination that requires just enough development assistance to create durable dependencies.

The Chip 4 alliance—the United States, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan—was supposed to coordinate these responses. It has instead become a study in distributed authority without distributed agreement. Each member validates its own export control decisions independently, creating a structure that resembles nothing so much as the Eastern Orthodox model of autocephalous churches: nominally unified, practically autonomous, and structurally incapable of binding collective action.

Trump’s threatened secondary sanctions have accelerated this fragmentation. When the United States declares that any firm facilitating Chinese technology access will face American market exclusion, it forces allies to choose between two dependencies. Most are choosing to hedge. South Korean memory manufacturers have maintained Chinese production facilities while publicly affirming commitment to allied coordination. European equipment makers have restructured supply chains to create plausible deniability. The sanctions threat has not unified the coalition. It has taught the coalition to hide.

The Measurement Problem

How would we know if the controls were working? This question, seemingly straightforward, reveals the deepest dysfunction in the current regime.

The stated objective is to deny China access to advanced AI capabilities. But AI capability is not a single number—it is a measure of how efficiently a technology fills different performance spaces, more akin to fractal dimension than to a simple metric. A chip optimized for training large language models may be useless for robotics applications. A model that excels at text generation may fail at scientific reasoning. The controls target specific hardware specifications (transistor density, memory bandwidth, interconnect speed) while the capabilities they seek to restrict exist in a different ontological space entirely.

This creates a version of the quantum Zeno effect applied to geopolitics. The iterative nature of export controls—constantly assessing Chinese capabilities and adjusting restrictions—functions as the “frequent measurement” that prevents observing the actual evolved state. Each policy adjustment resets the measurement, ensuring that the system can never settle into an observable equilibrium. Washington knows what China could build with last year’s technology. It cannot know what China has actually built with this year’s workarounds.

The evidence that does exist suggests the controls have achieved something, but not what their architects intended. Huawei’s Mate 60 Pro smartphone, released in August 2023, contained a domestically produced 7-nanometer chip—a capability American officials had confidently predicted China would not achieve for years. The chip was less efficient than comparable TSMC products, more expensive to manufacture, and reportedly suffered from yield problems. It also existed. The controls had not prevented the capability. They had changed its cost structure.

This is the pattern that recurs across the technology stack. Chinese firms have developed domestic alternatives to American electronic design automation software. The alternatives are inferior. They are also improving. Chinese equipment manufacturers have begun producing lithography systems that lag ASML by two or three generations. The gap is real. It is also narrowing. The controls have not stopped Chinese technological development. They have made it more expensive, more inefficient, and more determined.

The Resource Paradox

The deepest irony of the Trump administration’s technology competition strategy lies in what it ignores. While Washington obsesses over semiconductor fabrication, the physical substrate of that fabrication—the rare earth elements, the specialty chemicals, the ultrapure materials—remains overwhelmingly controlled by China.

The United States did not lose rare earth dominance to Chinese efficiency. It exported the environmental costs of processing to the only country willing to absorb them. American mines extracted the ore. Chinese facilities processed it into usable materials, accepting the toxic byproducts that American regulators would not permit. Now the dependency is structural. Neodymium for permanent magnets. Gallium for compound semiconductors. Germanium for fiber optics. Each sits in a supply chain that runs through Chinese processing facilities, regardless of where the raw material originated.

Trump’s response has been to invoke emergency authorities for domestic mining and processing. The rhetoric is aggressive. The mathematics are brutal. The average American mine takes 29 years to move from discovery to production. Federal permitting reforms, even if successful, address perhaps seven years of that timeline. The remaining decades involve state permits, environmental reviews, infrastructure development, and workforce training. No executive order accelerates geology.

China understands this asymmetry. In July 2023, Beijing imposed export licensing requirements on gallium and germanium—not outright bans, but procedural friction that creates uncertainty. The approach mirrors what the United States has done with semiconductors, turned back on its originator. The difference is that China controls the chokepoint that matters. Advanced chips require advanced materials. Advanced materials require Chinese processing. The fence runs both ways.

The Innovation Displacement

There is a case to be made that export controls, whatever their strategic limitations, have bought time for American technological leadership. The argument runs as follows: every year that China spends developing inferior domestic alternatives is a year that American firms spend extending their lead. The controls do not need to be permanent. They need to be durable enough to lock in an advantage that becomes self-sustaining.

The argument has a problem. It assumes that innovation follows predictable paths—that the technology China develops to circumvent controls will be merely imitative, a worse version of what America already has. The historical record suggests otherwise.

Japan’s experience under the Tokugawa shogunate’s isolation policy offers an instructive parallel. Cut off from European scientific developments, Japanese scholars created an entire institutional infrastructure—government translation agencies, specialized academies, networks of knowledge transmission—to extract what they could from the limited Dutch contact permitted at Nagasaki. The knowledge that emerged was not simply derivative. It was adapted, recombined, and in some cases advanced beyond its sources. Isolation did not prevent Japanese scientific development. It channeled it into different forms.

China’s response to semiconductor controls shows early signs of following this pattern. Huawei’s chiplet architecture—combining multiple smaller chips to achieve performance that single large chips would otherwise provide—represents not just a workaround but a genuine architectural innovation. The approach has limitations. It also has applications that American firms had not prioritized. The control regime is not just slowing Chinese development. It is redirecting it into spaces where American firms have less presence.

The neuromorphic computing programs that Chinese firms have accelerated since 2023 present a similar dynamic. These brain-inspired architectures process information through parallel distributed networks rather than the serial computation that dominates conventional chips. They are less mature than traditional approaches. They are also potentially transformative for applications in robotics, autonomous systems, and edge computing. The export controls that denied China access to the best conventional chips may have inadvertently accelerated Chinese investment in the architectures that could make conventional chips obsolete.

The Institutional Metabolism

The Trump administration has approached technology competition as a problem of willpower—apply enough pressure, and the desired outcome follows. The approach misunderstands the nature of the system it seeks to control.

Export control regimes are not policies. They are institutions, and institutions have metabolisms. The Bureau of Industry and Security, the Commerce Department office responsible for export control enforcement, processes thousands of license applications annually with a staff that has not meaningfully expanded since the Cold War. The interagency coordination required for major designations involves the State Department, the Defense Department, the intelligence community, and the White House—each with different priorities, different timelines, and different definitions of success.

When Trump declared export controls a “high-priority national security designation” while simultaneously exempting them from his broader deregulation efforts, he created a policy energy concentration that paradoxically increases entropy. Resources flow toward enforcement. Coordination mechanisms atrophy. The agencies that must work together to make controls effective instead compete for jurisdiction and credit.

The pattern resembles what organizational theorists call “threat-rigidity response”—institutions facing external pressure respond by rigidifying their structures, but the defensive posture itself generates new pathologies. The Commerce Department, under pressure to demonstrate enforcement vigor, has expanded the Entity List faster than firms can adjust their compliance systems. The result is not tighter control but widespread uncertainty, as companies struggle to determine whether their existing supply chains have suddenly become illegal.

The Path of Least Resistance

What happens next depends on which constraints prove binding. Three scenarios deserve consideration, each with distinct implications.

The first scenario assumes the current trajectory continues: escalating rhetoric, expanding restrictions, fragmenting alliances, and incremental Chinese adaptation. In this world, the technology competition becomes a war of attrition in which both sides pay mounting costs for diminishing advantages. American firms lose Chinese market access worth tens of billions annually. Chinese firms pay efficiency penalties that slow but do not stop their development. The semiconductor industry bifurcates into two partially incompatible ecosystems, each less innovative than a unified market would have been. Neither side wins. Both sides lose less than the other, or believe they do.

The second scenario assumes a crisis forces recalibration. The trigger could be a supply chain disruption—a Chinese rare earth embargo, a natural disaster affecting Taiwanese fabrication, a cyberattack on critical manufacturing infrastructure. In this world, the mutual dependencies that export controls have obscured suddenly become visible, and the political incentives shift toward managed competition rather than technological containment. This scenario requires leaders in both Washington and Beijing to accept limits on their ambitions. Nothing in current political dynamics suggests such acceptance is imminent.

The third scenario assumes the competition transcends its current technological substrate. Artificial intelligence does not stand still. The chips that matter in 2025 may not be the chips that matter in 2030. Quantum computing, biological computation, neuromorphic architectures—each represents a potential discontinuity that could render current control regimes irrelevant. In this world, the winner is not the country that best restricts the other’s access to existing technology but the country that best positions itself for technologies that do not yet exist. The export control apparatus, optimized for fighting the last war, becomes an expensive irrelevance.

The most likely outcome combines elements of all three: continued escalation in the near term, crisis-driven adjustments in the medium term, and technological displacement in the long term. The Trump administration will claim victories measured in Entity List additions and enforcement actions. The victories will be real. They will also be incomplete, contested, and potentially counterproductive.

The Fence and What Lies Beyond

There is a moment in every technological competition when the terms of competition shift—when the capabilities that mattered yesterday become commodities and the capabilities that will matter tomorrow remain undefined. The United States and China are approaching such a moment, and neither country’s strategy accounts for it.

The Trump administration has inherited a control regime built on the assumption that denying China access to advanced semiconductors would deny China access to advanced artificial intelligence. The assumption was reasonable in 2022. It is increasingly questionable in 2025. The most capable AI systems now emerging depend less on raw computational power than on architectural innovations, training methodologies, and data curation practices that no export control can restrict. The fence protects a perimeter that the competition has already moved beyond.

This does not mean the controls are worthless. They impose costs. They create delays. They force Chinese firms to divert resources from innovation to circumvention. These are real effects with real strategic value. But they are not the effects that justify the regime’s existence, and they come with costs of their own: alliance fragmentation, supply chain disruption, innovation displacement, and the slow erosion of the international trading system that American prosperity depends upon.

The Trump administration shows no sign of recognizing these trade-offs. The rhetoric of technological dominance admits no complexity, no cost, no limit. The policy apparatus grinds forward, adding names to lists and threats to allies, measuring success in inputs rather than outcomes.

Somewhere in Shenzhen, engineers are designing the workaround that will render the latest restrictions obsolete. Somewhere in Washington, officials are preparing the next round of controls to address the workarounds they have not yet seen. The competition continues. The fence grows higher. And the question that matters—whether any of this serves American interests—remains carefully unasked.