The Deterrent That Became a Target

China's missile arsenal can now threaten every American base in the Western Pacific. The forces meant to prevent war may instead invite the opening salvo of one. Washington faces choices it has spent decades avoiding.

The Target That Shoots Back

For seven decades, American strategists treated forward-deployed forces as the cornerstone of Pacific deterrence. Troops in Japan, aircraft in Guam, ships rotating through the Philippines—these were not merely military assets but political commitments made physical. An attack on them would be an attack on America itself. The logic was elegant: by placing forces in harm’s way, Washington removed any doubt about its willingness to fight.

That logic assumed American forces could survive long enough to matter.

China’s missile arsenal has quietly invalidated this assumption. The People’s Liberation Army now fields more than 1,250 ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles with ranges between 500 and 5,500 kilometres—enough to hold every major American installation in the Western Pacific at risk simultaneously. The DF-26, which Chinese military planners call the “Guam Killer,” can strike targets 4,000 to 5,000 kilometres away. The DF-21D can reach anything within 2,150 kilometres. Newer hypersonic systems like the DF-17 and DF-27 compress warning times to minutes.

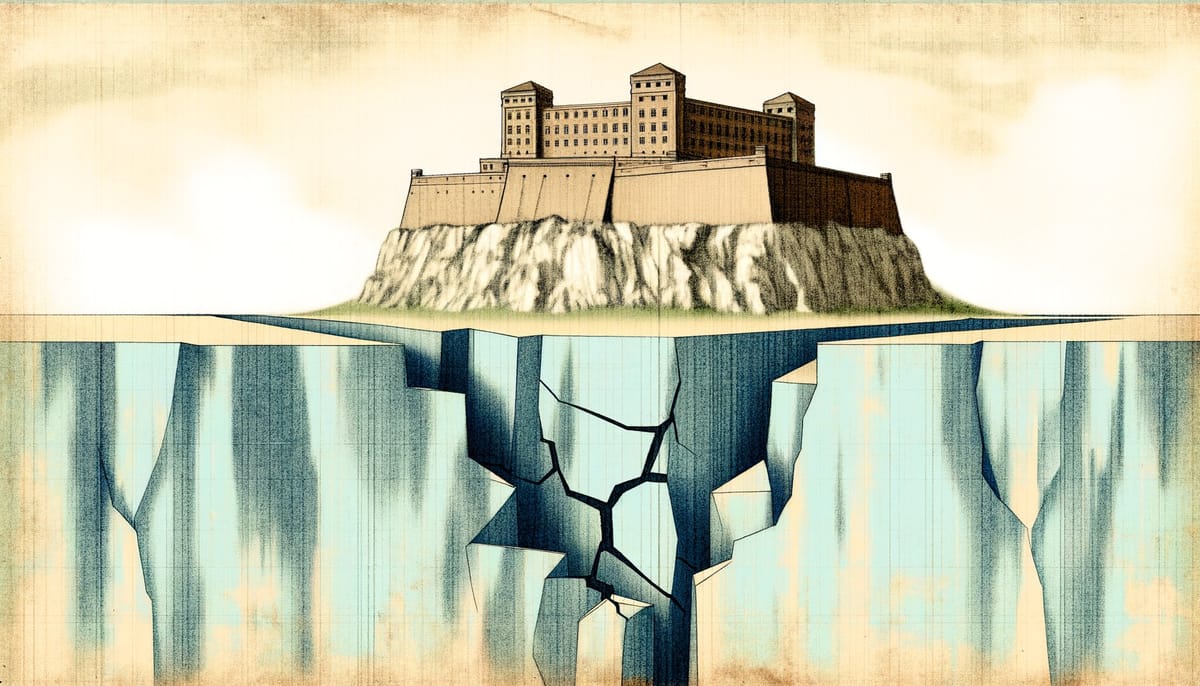

Pentagon assessments are blunt: Chinese missiles could “close the runways and taxiways at U.S. forward air bases in Japan, Guam, and other Pacific locations in the first critical days—and even weeks—of a war.” The question is no longer whether China can threaten American bases. It is whether those bases still deter, or whether they have become what strategists most fear: hostages rather than shields.

Deterrence Inverted

The traditional case for forward deployment rests on three pillars: signalling commitment, enabling rapid response, and reassuring allies. American troops stationed in South Korea and Japan serve as “tripwires”—their presence guarantees that any aggression triggers immediate American involvement. This worked brilliantly against adversaries who could not credibly threaten those forces before a conflict began.

China has systematically dismantled each pillar.

Consider signalling. A tripwire deters only if the adversary believes attacking it will prove costly. But if China can neutralise American bases in the opening hours of a conflict—before reinforcements arrive, before political will crystallises—the tripwire becomes a speed bump. Worse, the very concentration of forces that once demonstrated resolve now presents lucrative targets. Kadena Air Base in Okinawa hosts the largest American air wing in the Pacific. It also sits within range of thousands of Chinese missiles. The signal sent is no longer “attack us and face certain retaliation.” It is “attack us first, before we can respond.”

Rapid response suffers similar erosion. Forward bases were designed to project power quickly into contested zones. But projection requires survivable infrastructure—runways, fuel depots, maintenance facilities. A Stimson Center analysis found that even a modest Chinese missile barrage could crater runways and destroy parked aircraft faster than they could be repaired or replaced. The Pacific Air Forces commander has acknowledged that American forces are “working to dampen Chinese missile advantage”—a tacit admission that the advantage currently belongs to Beijing.

Alliance reassurance presents the deepest paradox. American bases exist partly to convince allies that Washington will fight for them. Yet those same allies increasingly recognise that hosting American forces makes them primary targets. Okinawa’s population has protested American bases for decades; China’s missile buildup has transformed abstract concerns about sovereignty into concrete fears about survival. The deployment of Japanese missile capabilities on Okinawa’s outer islands has intensified local demands for American withdrawal—a paradox where indigenous military buildup amplifies pressure to expel the ally.

The arithmetic is unforgiving. America maintains at least 66 significant defence sites across the Pacific, including 14 bases in Japan hosting roughly 53,000 troops, 8 bases in South Korea with 24,000 troops, and expanding access points in the Philippines and Australia. Each installation requires protection. Each presents a target. China need not destroy them all—merely threaten them credibly enough to paralyse decision-making in the critical hours when deterrence either holds or fails.

The Adaptation Dilemma

The Pentagon has not ignored this problem. The 2022 National Defense Strategy explicitly identifies China as the “pacing challenge” and calls for “integrated deterrence” that combines military, diplomatic, and economic tools. More concretely, the Air Force has developed Agile Combat Employment—a doctrine that “shifts operations from centralised physical infrastructures to a network of smaller, dispersed locations that can complicate adversary planning.”

ACE represents genuine strategic innovation. Rather than concentrating aircraft at a handful of large bases, it envisions forces dispersing across dozens of austere airfields, civilian airports, and improvised strips. The goal is to present China with a targeting problem so complex that no missile barrage can neutralise American airpower.

The concept sounds elegant. Implementation reveals brutal constraints.

Dispersal multiplies logistics. A single F-35 requires roughly 50 maintenance personnel, specialised equipment, secure communications, and a steady flow of fuel, munitions, and spare parts. Spreading aircraft across 30 locations instead of 3 does not reduce these requirements—it multiplies them by a factor of ten while eliminating economies of scale. The metabolic scaling that governs biological systems—where larger organisms are more energy-efficient per unit mass—inverts for military dispersal. Smaller, distributed units consume disproportionately more resources per capability delivered.

Coordination costs compound the challenge. Hierarchical command structures achieve resilience precisely by compressing information—each level filters data so subordinates don’t need complete system knowledge. Dispersal shatters this architecture. Research on organisational entropy reveals that distributed coordination doesn’t merely increase logistical complexity; it creates entropy at the human decision-making level that must itself be managed. The psychological burden of operating from unfamiliar locations, with degraded communications and uncertain supply lines, extracts costs that doctrine papers rarely acknowledge.

Then there is the infrastructure itself. ACE depends on access to civilian airfields across allied nations. But those airfields serve commercial purposes. Commandeering them for military use disrupts the economic systems that maintain them. Like hermit crabs that cannot extract shells from living gastropods, ACE cannot seize civilian infrastructure during peacetime without killing the host. The doctrine assumes access that political realities may not provide.

Guam illustrates the broader dysfunction. The island hosts Joint Region Marianas, America’s most significant permanent base in the Western Pacific. The Pentagon has committed to building a comprehensive missile defence system there—the first of its kind designed to protect an entire territory rather than point targets. Yet a Government Accountability Office assessment found the project facing delays and planning problems that push completion into the early 2030s. The multi-year installation period creates a paradox: infrastructure under construction becomes strategically valuable as a target before it becomes operationally valuable as a defence.

The Alliance Fracture

Forward deployment’s deepest vulnerability may be political rather than military. American bases in Asia exist within a web of Status of Forces Agreements, host-nation support arrangements, and bilateral security treaties. Each represents a negotiated compromise between American operational requirements and allied sovereignty concerns. China has learned to target these seams.

Economic coercion offers the clearest mechanism. When South Korea agreed to host the THAAD missile defence system in 2017, China responded with sanctions that cost Korean businesses billions of dollars. The message was unmistakable: hosting American military capabilities carries economic penalties. Belt and Road investments create similar leverage, offering infrastructure financing to nations that might otherwise deepen military ties with Washington.

These pressures function as what financial markets would call margin calls—artificially inflating the maintenance costs of extended deterrence commitments until allies can no longer afford them. The patron-client relationship that once seemed stable now exhibits the characteristics of dysfunctional family systems, where demands for burden-sharing paradoxically lock both parties into rigid roles that neither can escape.

Japan presents the most consequential case. The alliance remains robust at the strategic level, but operational frictions accumulate. Okinawa hosts 70% of American military facilities in Japan on 0.6% of Japanese territory. Local opposition has blocked base relocations for decades. The Ryukyuan population increasingly identifies as indigenous rather than merely Japanese—a legal distinction that could trigger consultation requirements under international frameworks governing non-self-governing territories.

The Philippines offers a different lesson. Manila has oscillated between embracing and rejecting American military presence depending on which president holds power. The Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement that granted American forces access to nine Philippine bases was nearly scrapped under President Duterte; it was restored under President Marcos Jr. This volatility reveals that most access agreements function as what property lawyers call easements in gross—personal rights tied to specific administrations rather than permanent features of the geopolitical landscape.

Australia represents the alliance’s geographic backstop—far enough from Chinese missiles to offer sanctuary, close enough to the theatre to enable operations. Darwin hosts rotating American Marines; Pine Gap provides critical intelligence. But even Australia faces constraints. Indigenous land rights, environmental regulations, and domestic politics all limit how quickly American forces can expand their footprint. The Northern Territory’s sparse infrastructure cannot absorb major force increases without years of investment.

What Breaks First

Continue current trends and the system fails in one of three ways.

The first failure mode is military. China achieves the capability to neutralise American forward bases quickly enough that Washington cannot escalate before the fait accompli is complete. Taiwan falls in days. American forces in Japan and Guam absorb punishing strikes but cannot mount effective counterattacks before Beijing consolidates control. The alliance structure survives formally but loses credibility permanently.

The second failure mode is political. Allied populations, confronting the reality that hosting American forces makes them targets rather than protectors, demand withdrawal. Japan asks American troops to leave Okinawa. The Philippines cancels access agreements. South Korea seeks accommodation with Beijing. The alliance structure dissolves not through military defeat but through democratic choice.

The third failure mode is economic. The cost of hardening bases, dispersing forces, and maintaining credible deterrence across thousands of miles exceeds what American taxpayers will fund. Congress, facing demands for domestic spending and sceptical of endless Pacific commitments, cuts defence budgets. The military cannot sustain the posture that strategy requires. Deterrence erodes through fiscal exhaustion.

Each pathway leads to the same destination: a Western Pacific where Chinese military dominance becomes the default condition, where American security guarantees ring hollow, and where allies must choose between accommodation and abandonment.

The Uncomfortable Choices

Reversing this trajectory requires accepting trade-offs that American strategists have long avoided.

Option one: strategic dispersal at scale. This means genuinely implementing ACE—not as a doctrinal aspiration but as a funded, exercised, diplomatically negotiated reality. It requires pre-positioning equipment across dozens of locations, securing access agreements that survive electoral changes, and accepting that dispersed forces will be less efficient than concentrated ones. The cost runs into tens of billions of dollars annually. The benefit is a targeting problem that exceeds Chinese planning capacity.

The trade-off is operational complexity. Dispersed forces are harder to command, slower to mass, and more dependent on logistics that adversaries can interdict. They also require allies to accept military activities across their territories—activities that generate domestic opposition and invite Chinese economic retaliation.

Option two: selective withdrawal. Rather than defending everything, Washington could concentrate forces at locations beyond Chinese missile range while maintaining smaller tripwire presences forward. Guam becomes a fortress. Australia hosts major capabilities. Japan and South Korea retain symbolic American presences but assume primary responsibility for their own defence.

The trade-off is alliance credibility. Allies who see American forces withdrawing may conclude that Washington has already decided not to fight for them. Some may seek nuclear weapons. Others may accommodate Beijing. The alliance structure that has preserved Pacific stability for seven decades could unravel within one.

Option three: offensive deterrence. Instead of defending bases, Washington could threaten Chinese assets with equivalent destruction. If China can crater American runways, America can crater Chinese runways—and Chinese ports, and Chinese command centres, and Chinese leadership facilities. Deterrence shifts from denial to punishment.

The trade-off is escalation risk. Offensive deterrence works only if both sides believe the other will actually execute threats. Against a nuclear-armed adversary, this logic leads toward scenarios that neither side can control. The Cuban Missile Crisis lasted thirteen days. A Pacific crisis might last thirteen minutes.

None of these options is attractive. Each demands sacrifices that American politics has proven reluctant to make. Yet the alternative—continuing to treat forward deployment as an unquestioned good while China methodically acquires the means to destroy it—guarantees the worst outcome: a deterrent that deters nothing.

FAQ: Key Questions Answered

Q: Can missile defence protect American bases in the Pacific? A: Current technology cannot defeat saturation attacks. China possesses enough missiles to overwhelm any plausible defence system through sheer volume. The Guam defence project, if completed, might protect that single island—but Japan, South Korea, and the Philippines would remain vulnerable.

Q: Why don’t allies simply build their own defences? A: Some are trying. Japan has committed to doubling defence spending and acquiring counterstrike capabilities. But building military capacity takes decades, and allied defence industries cannot match Chinese production rates. The gap between threat and response continues to widen.

Q: Would withdrawing American forces invite Chinese aggression? A: Possibly—but so might maintaining forces that cannot survive. The question is not whether presence deters, but whether presence that can be destroyed in the opening hours of a conflict deters more than presence that survives. There is no cost-free option.

Q: Is war between America and China inevitable? A: No. Deterrence can work even when both sides possess devastating capabilities—the Cold War demonstrated this. But deterrence requires credibility, and credibility requires forces that can fight effectively. The current posture satisfies neither condition.

The Honest Answer

Forward deployment has not yet become a liability. But it is becoming one.

The forces stationed across the Pacific still serve purposes beyond warfighting: they reassure allies, enable peacetime operations, and demonstrate commitment. These functions retain value even as military utility erodes. The challenge is that adversaries observe the erosion too. Every war game that ends with American bases cratered and aircraft destroyed teaches the same lesson: the emperor’s clothes are thinning.

The honest answer to the question—does forward deployment remain a deterrent?—is that it depends on what China believes. If Beijing concludes that American forces can be neutralised quickly enough to present Washington with a fait accompli, forward deployment becomes an invitation to aggression rather than a warning against it. If Beijing remains uncertain—if the dispersal concepts work, if allied resolve holds, if American political will proves more durable than expected—then deterrence may yet hold.

Uncertainty is not a strategy. But for now, it is all that remains.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- 2022 National Defense Strategy - Primary source for U.S. strategic posture and “integrated deterrence” framework

- 2024 China Military Power Report - Pentagon’s assessment of Chinese missile capabilities and military modernization

- Stimson Center analysis on Chinese missile threats - Detailed assessment of base vulnerability to missile attack

- Air Force Doctrine Note on Agile Combat Employment - Official doctrine for dispersed operations

- CGSR workshop on extended deterrence - Expert discussion of alliance credibility challenges

- Business Insider on Guam missile defence delays - Reporting on implementation challenges

- CEMIPOS on Ryukyuan identity and U.S. bases - Analysis of indigenous perspectives on forward deployment

- CSIS Missile Threat Project - Technical specifications of Chinese missile systems