The Decade That Decides: America, China, and Russia's Collision Course

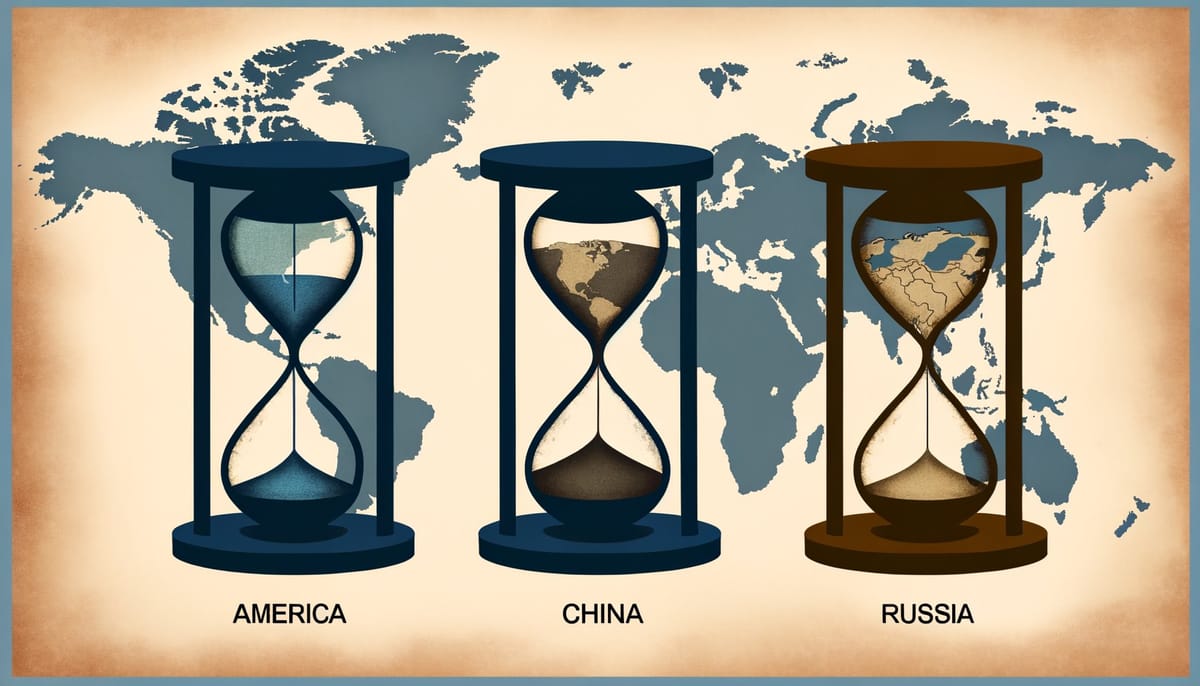

Three great powers operate on three incompatible timescales. Washington resets every four years, Beijing plans through 2035, Moscow thinks in generations. The next decade will reveal which clock keeps better time—and whether any of them can be synchronized before collision.

The Decade That Decides

Three capitals. Three clocks. Three irreconcilable timelines.

In Beijing, planners mark 2035 as the horizon for “basically realizing socialist modernization.” In Moscow, strategists think in generational cycles, measuring victory across decades rather than electoral terms. In Washington, the clock resets every four years—sometimes every two—as administrations arrive with new priorities and depart before their strategies mature.

This temporal incommensurability will define the next decade more than any weapon system, trade deal, or diplomatic breakthrough. The United States, China, and Russia do not merely pursue different goals. They experience time itself differently. And that difference determines who can wait, who must act, and who will miscalculate.

What Washington Sees (And What It Misses)

The Biden administration’s 2022 National Security Strategy declared America to be “in the early years of a decisive decade” where “the terms of geopolitical competition between the major powers will be set.” The framing was deliberate: urgency without panic, competition without conflict. China was named “the most consequential long-term geopolitical challenge.” Russia posed “an immediate threat.”

The distinction matters. Immediate threats demand immediate responses. Long-term challenges permit strategic patience. But the framework contains a hidden assumption: that Washington can sequence its attention, addressing Russia now while preparing for China later.

Events have already complicated this logic. The war in Ukraine consumed ammunition stockpiles, diplomatic bandwidth, and alliance cohesion that strategists had mentally allocated to the Indo-Pacific. European allies, promised a “pivot to Asia,” instead found themselves hosting American troops and buying American weapons to counter Russian aggression on their doorstep.

The numbers expose the strain. Before the Ukraine conflict, the United States produced 240,000 artillery shells annually—barely 40 days of Ukrainian consumption at wartime rates. Russia, through command-economy mobilization, increased production 200-300 percent. This production gap compounds monthly. Each quarter of delay in building Western industrial capacity requires additional months to overcome.

Yet the deeper problem is not industrial. It is institutional. American strategy operates on quarterly rhythms: congressional appropriations cycles, electoral calendars, quarterly earnings reports from defense contractors. These rhythms create what military planners call “temporal compression”—the tendency to prioritize visible, immediate actions over invisible, long-term investments.

China’s 15th Five-Year Plan, by contrast, positions the period through 2030 as “a critical stage for basically realizing socialist modernization by 2035.” Note the nesting: a five-year plan within a fifteen-year trajectory within a multi-generational project. Beijing’s planners think in stacked timescales. Washington’s planners struggle to think past the next election.

Beijing’s Patient Gamble

Xi Jinping’s formative experience was chaos. During the Cultural Revolution, his father was imprisoned for sixteen years. His half-sister died by suicide. The family home was ransacked. Young Xi was labeled a “black element bastard” and exiled to rural Shaanxi for seven years of manual labor.

From this crucible emerged a leader for whom disorder represents existential threat. The Party’s survival requires absolute unity. Personal suffering legitimizes authority. And above all: chaos must be prevented through preemptive control.

This psychology shapes China’s strategic patience. Xi can wait because he controls the clock. Term limits have been abolished. Potential rivals have been purged. The Party apparatus answers to one man in ways unseen since Mao. When Chinese strategists speak of “the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation,” they mean a project measured in decades, not electoral cycles.

But patience has limits. The year 2027 carries symbolic weight: the centenary of the founding of the People’s Liberation Army. Anniversary psychology matters. Individual trauma research identifies “anniversary effects” where significant dates trigger compulsive re-enactment behaviors. For a leader raised in “revolutionary family virtues and traditions,” the incomplete victory of 1949—when Nationalist forces retreated to Taiwan—represents an open wound in the revolutionary narrative.

Reunification is not merely policy for Xi. It is filial duty.

Yet China faces constraints that ideology cannot wish away. Demographic decline has arrived faster than projections suggested. The working-age population is shrinking. The property sector—once the engine of growth—has become a source of systemic risk. Youth unemployment reached levels embarrassing enough that Beijing stopped publishing the figures.

The economic model that delivered three decades of growth is exhausted. The 15th Five-Year Plan’s emphasis on “high-quality development” and “technological self-reliance” acknowledges this reality. But transitioning from investment-driven growth to innovation-driven growth requires precisely the kind of decentralized experimentation that Xi’s centralizing instincts suppress.

Here is China’s dilemma: the capabilities needed to challenge American hegemony require economic dynamism, but the control mechanisms needed to maintain Party supremacy constrain that dynamism. Xi has chosen control. The next decade will reveal whether that choice was wisdom or hubris.

Moscow’s Frozen Clock

Vladimir Putin’s formative moment came on December 5, 1989. He was a mid-level KGB officer in Dresden when protesters surrounded the Soviet compound. He called Moscow for instructions. The answer: “Moscow is silent.”

The empire abandoned its agents at the moment of maximum vulnerability. Putin learned that institutions exist only as long as personal networks sustain them. Loyalty is transactional. Weakness invites predation. And the West will exploit any opening.

Russia’s 2021 National Security Strategy frames the country as pursuing “strategic independence” in a multipolar world. The language is defensive: strengthening deterrence, preventing violations of the UN Charter, developing partnerships with China and other non-Western powers. But the strategy was written before the invasion of Ukraine transformed Russia’s position from revisionist power to international pariah.

The war has revealed both Russian strengths and Russian pathologies. The military performed worse than expected in the opening months, suffering from corruption, poor logistics, and tactical rigidity. But the economy proved more resilient than Western sanctions architects anticipated. Russia found buyers for its energy exports. It mobilized industrial capacity that analysts had dismissed as obsolete. It demonstrated willingness to absorb casualties that would be politically unsustainable in Western democracies.

Putin operates on generational timescales. The neural map of “legitimate” Russian territory—formed through centuries of imperial expansion and Soviet consolidation—does not update easily. Research on phantom limb pain shows that the brain’s map of an amputated limb endures unchanged years after amputation. The neural architecture refuses revision. Post-1991 Russian territorial consciousness may operate similarly: Ukraine, Belarus, and the Baltic states remain part of the mental map regardless of legal reality.

This creates a structural problem that no treaty can solve. Western diplomats negotiate over borders and security guarantees. Putin experiences the conversation as a discussion about which parts of Russia’s body will be amputated. The categories do not translate.

The next decade for Russia depends on variables Moscow does not control. Energy prices. Chinese willingness to provide economic lifelines. Western unity or fragmentation. Putin’s health. The war in Ukraine has frozen Russia’s trajectory: neither the decisive victory that would validate the invasion nor the catastrophic defeat that might trigger regime change. Stalemate by exhaustion.

The Triangular Trap

The three powers do not form a stable triangle. They form an unstable system where each actor’s moves constrain the others’ options in ways that compound unpredictably.

Consider the semiconductor question. The United States has imposed export controls designed to deny China access to advanced chipmaking technology. The logic is straightforward: chips are the foundation of modern military capability, and America should not enable its competitor’s military modernization.

But the controls create second-order effects. China accelerates domestic chip development, accepting short-term pain for long-term independence. Taiwan’s strategic importance intensifies—the island produces over 90 percent of the world’s most advanced chips—making conflict more consequential and perhaps more tempting. American allies in Europe and Asia face pressure to choose sides, fracturing the supply chains that made globalization profitable.

Russia, meanwhile, becomes increasingly dependent on Chinese technology as Western sanctions close alternative sources. This dependence shifts the Russia-China relationship from partnership of convenience to asymmetric dependency. Moscow needs Beijing more than Beijing needs Moscow. The implications for Central Asia, the Arctic, and the global energy market remain unclear.

The system exhibits what complexity theorists call emergent behavior: outcomes that no individual actor intended but that arise from the interaction of multiple agents pursuing their own objectives. Nobody planned for a world where American export controls push China toward semiconductor self-sufficiency while Russian energy dependence gives Beijing leverage over Moscow while European energy insecurity drives rearmament that strains NATO cohesion. Yet here we are.

What Breaks First

The next decade will stress-test assumptions that policymakers treat as fixed.

American assumptions under pressure:

Alliance solidarity. NATO demonstrated remarkable unity in response to Ukraine. But unity has costs. European allies are spending more on defense, which is what Washington demanded. They are also developing autonomous capabilities, which is not. The more Europe arms itself, the less it needs American protection. The more it needs American protection, the less it arms itself. This paradox has no stable resolution.

Economic leverage. Sanctions against Russia were supposed to demonstrate that integration into the Western financial system creates vulnerability. They did. But they also demonstrated that alternatives exist. Russia found workarounds. China took notes. The next time Washington reaches for the sanctions weapon, targets will be better prepared.

Technological superiority. The assumption that American innovation will always outpace competitors depends on continued investment in basic research, STEM education, and immigration of skilled workers. All three face political headwinds. The pipeline of talent that feeds American technological dominance is not self-sustaining.

Chinese assumptions under pressure:

Demographic dividend. China grew rich before it grew old, but the demographic transition is now accelerating. The working-age population peaked around 2015. The dependency ratio—workers supporting retirees—will worsen through 2035 and beyond. Automation can partially compensate, but robots do not consume, and consumption is supposed to replace investment as the growth driver.

Party legitimacy through performance. The implicit bargain—citizens accept authoritarian governance in exchange for rising living standards—depends on living standards continuing to rise. If growth stalls, the bargain requires renegotiation. Xi has prepared for this by emphasizing nationalism and ideological purity over material prosperity. Whether Chinese citizens accept the new terms remains untested.

American decline. Chinese strategists have long believed that American power is waning and that patience will be rewarded. But American decline has been predicted before. The 1980s brought confident projections of Japanese dominance. The 2008 financial crisis prompted obituaries for American capitalism. Both times, reports of American death proved exaggerated.

Russian assumptions under pressure:

Western fragmentation. Putin has consistently bet that Western democracies lack the stamina for sustained confrontation. Ukraine has partially vindicated this bet—support has frayed at the margins—but not decisively. The question for the next decade is whether Western publics will tire of the costs before Russian capacity is exhausted.

Chinese partnership. Russia’s “no limits” partnership with China is limited by Chinese interests. Beijing values Russian energy and diplomatic support but has no desire to be drawn into a confrontation with the West over Ukraine. As Russia’s dependence on China deepens, the partnership becomes less equal. Putin may discover that junior partner status carries its own humiliations.

Regime stability. Putin has eliminated rivals and concentrated power. But concentrated power creates succession problems. The system depends on one man’s health, judgment, and continued grip on the security services. No mechanism exists for orderly transition. The next decade may force the question.

Trajectories

Three scenarios bracket the range of plausible futures.

Managed competition. The powers establish informal rules of the road that prevent direct conflict while competition continues in economic, technological, and proxy dimensions. Taiwan remains ambiguous. Ukraine reaches a frozen settlement. The global economy fragments into blocs but does not collapse. This is the best realistic outcome—not peace, but the absence of catastrophic war.

Cascading crisis. A triggering event—Taiwan, a Baltic provocation, economic collapse in China—initiates a sequence that overwhelms crisis management mechanisms. The powers lack the communication channels and mutual understanding that Cold War adversaries developed over decades. Escalation occurs not because anyone wants it but because no one knows how to stop it.

Asymmetric exhaustion. One power’s internal contradictions resolve faster than the others’. Russia’s economy cannot sustain indefinite war. China’s demographic decline accelerates. American political dysfunction paralyzes strategic adaptation. The “winner” is whoever remains standing when the others stumble. This is not victory in any meaningful sense—merely survival by default.

The most likely trajectory combines elements of all three: managed competition punctuated by crises that are contained but not resolved, with gradual shifts in relative power as internal contradictions play out at different speeds.

The Interventions That Matter

Policy recommendations for great-power competition tend toward the grandiose: “Strengthen alliances.” “Invest in technology.” “Maintain deterrence.” Such advice is not wrong, merely useless. Everyone already agrees with it. The question is which specific investments, at what cost, accepting which trade-offs.

Three interventions could shift trajectories:

Industrial mobilization. The production gap between Western and Russian/Chinese manufacturing capacity is not a bug but a feature of post-Cold War economic optimization. Just-in-time supply chains minimize inventory costs but maximize vulnerability. Rebuilding defense industrial capacity requires accepting inefficiency—stockpiles that may never be used, production lines that operate below optimal utilization, workers trained for contingencies that may not materialize. The cost is real. The alternative is discovering, mid-crisis, that the arsenal of democracy cannot produce enough ammunition.

Diplomatic architecture. The Cold War produced arms control agreements, hotlines, and confidence-building measures that reduced the risk of accidental escalation. The current competition lacks equivalent infrastructure. Building it requires talking to adversaries, which domestic politics in all three capitals makes difficult. But the alternative is managing crises without the communication channels that prevented the Cold War from turning hot.

Succession planning. All three powers face leadership transitions within the next decade. Biden is 82. Putin is 72 and has concentrated power in ways that preclude orderly succession. Xi has eliminated term limits but not mortality. The transitions will be managed differently—American elections, Russian palace intrigue, Chinese Party mechanisms—but all create windows of vulnerability and opportunity. Preparing for these transitions, rather than assuming current leaders are permanent, is elementary prudence that strategists often neglect.

FAQ: Key Questions Answered

Q: Will China invade Taiwan in the next decade? A: The risk is real but not inevitable. Chinese military capabilities will likely reach the threshold for a credible invasion attempt by 2027-2030, but capability does not equal intention. The costs of failure—military, economic, and political—remain prohibitive. The most dangerous scenario is not a calculated invasion but a crisis that escalates beyond anyone’s control.

Q: Can sanctions force Russia to end the war in Ukraine? A: Sanctions have imposed costs but have not changed Russian behavior. The economy adapted faster than expected, finding alternative markets and workarounds. Sanctions work best as part of a broader strategy that includes military support to Ukraine and diplomatic off-ramps. Alone, they are insufficient.

Q: Is the United States in decline? A: American power is not declining in absolute terms—the economy remains the world’s largest, the military the most capable, the technology sector the most innovative. But relative power is shifting as China grows and other actors develop capabilities that constrain American freedom of action. The question is not whether America is declining but whether it can adapt to a world where dominance is no longer possible.

Q: What role will climate change play in great-power competition? A: Climate change will stress all three powers differently. Russia faces permafrost thaw that threatens infrastructure and could release ancient pathogens. China confronts water scarcity and extreme heat in agricultural regions. The United States must manage intensifying hurricanes and wildfires while maintaining global commitments. Climate is a threat multiplier that will compound other stresses without replacing them.

The Clock That Matters

The decisive decade will not be decided by any single event. It will be decided by which system proves most capable of adapting to pressures that none of its architects anticipated.

America’s advantage is adaptability—the capacity to course-correct through elections, market signals, and institutional renewal. Its disadvantage is short-termism, the quarterly rhythm that sacrifices long-term investment for immediate returns.

China’s advantage is strategic patience—the ability to pursue multi-decade objectives without electoral interruption. Its disadvantage is rigidity, the centralization that prevents the experimentation needed for innovation.

Russia’s advantage is resilience—the capacity to absorb punishment that would break other societies. Its disadvantage is stagnation, the inability to generate the economic dynamism needed to compete over the long term.

The next decade will reveal which advantages matter more than which disadvantages. The answer is not predetermined. It depends on choices that have not yet been made, by leaders who have not yet been tested, in crises that have not yet emerged.

The clocks are ticking. They keep different time.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- Biden Administration National Security Strategy (2022) - Primary source for U.S. strategic framing of the “decisive decade”

- China’s 15th Five-Year Plan Recommendations - Official CCP document outlining 2026-2030 development priorities

- Russia’s National Security Strategy (2021) - Foundational document for Russian strategic posture

- NPR investigation on permafrost thaw and anthrax - Climate security implications for Russia

- Intergenerational justice research - Framework for understanding long-term strategic planning

- Kessler syndrome analysis - Space domain competition dynamics

- Lagrange point stability research - Orbital mechanics as strategic metaphor