The Countdown That Isn't

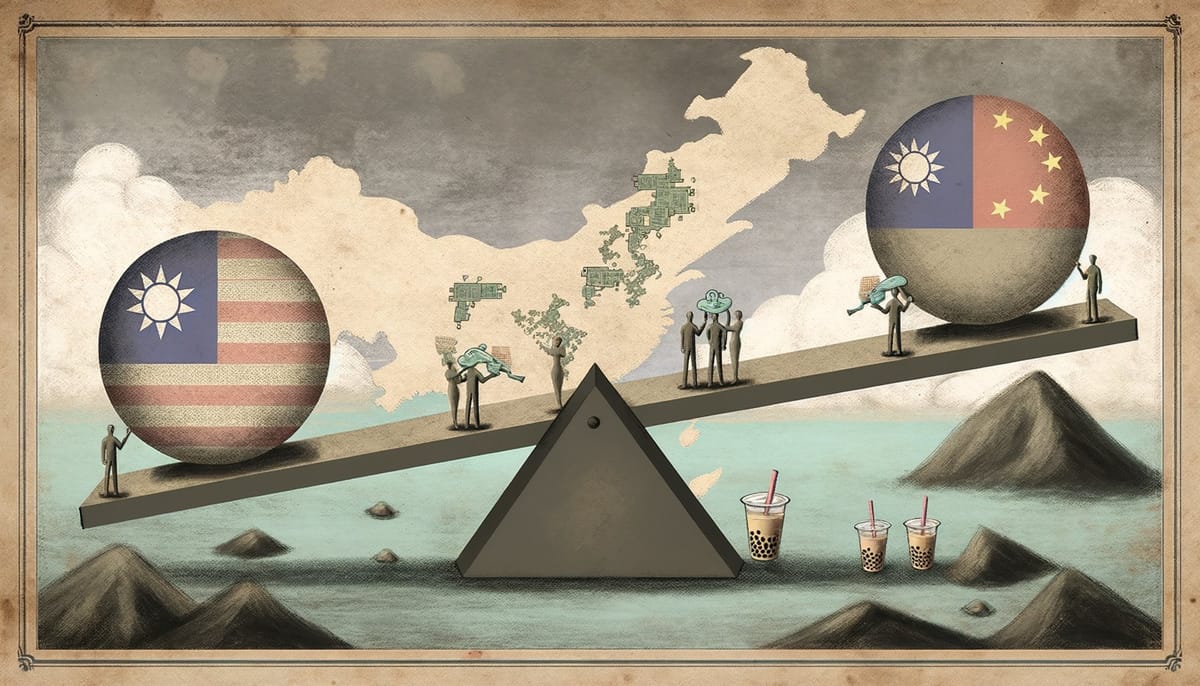

Taiwan exists in a state of permanent almost. Almost a country. Almost at war. Almost reunified. For seventy-five years, the island has occupied a liminal space that international law cannot classify and strategic planners cannot resolve.

The Structural Trap

Start with Beijing’s problem. The Chinese Communist Party has made Taiwan’s reunification a core legitimacy claim for seven decades. This is not mere rhetoric. The “Century of Humiliation” narrative positions territorial wholeness as an unpaid ancestral debt—a Confucian obligation that cannot be forgiven, only discharged. Performance legitimacy through economic growth once provided the CCP with breathing room. Growth is slowing. The debt remains.

Xi Jinping’s consolidation of power has made this worse, not better. By installing an all-loyalist Politburo Standing Committee—seven of seven members selected for personal fealty—Xi has eliminated the internal counterweights that might counsel patience. He has also created a succession paradox: any successor strong enough to continue his agenda would threaten him during the transition, while any successor weak enough to be safe would lack the authority to maintain it. The system cannot produce a legitimate heir. This makes Xi’s personal timeline the only timeline that matters, and Xi is sixty-eleven years old.

But personal urgency does not translate into operational feasibility. The logistics of amphibious invasion remain brutal. Military analysts estimate Taiwan would require thirty million tons of materiel to conquer—exceeding the Normandy invasion by orders of magnitude. The PLA has never conducted a contested amphibious landing. Taiwan’s geography—mountainous, urbanized, with few suitable beaches—favors defenders. The mathematics are unforgiving.

More troubling for Beijing: Taiwan has developed its own hypersonic strike capability with ranges exceeding 2,000 kilometers, putting northern Chinese cities under threat. This creates a symmetrical decapitation risk. Any Chinese attempt to eliminate Taiwan’s leadership invites retaliation against the mainland’s. The invasion calculus has shifted from difficult to mutually catastrophic.

So Beijing faces a structural bind. It cannot abandon the reunification claim without undermining regime legitimacy. It cannot achieve reunification through force without accepting catastrophic risk. It cannot wait indefinitely because the very factors that make invasion difficult—Taiwanese military modernization, identity consolidation, international support—compound over time.

The Island That Drifted Away

Taiwan’s transformation is the variable Beijing least controls and most fears.

In 1992, a majority of Taiwan’s population identified as “Chinese” or “both Chinese and Taiwanese.” By 2024, over sixty-seven percent identify as exclusively Taiwanese. This is not a policy outcome. It is a generational rupture. Young Taiwanese have no memory of martial law, no connection to the mainland, no investment in the Republic of China’s claim to represent all of China. They have grown up in a democracy, consumed different media, developed different cultural reference points. The island has drifted away not through independence declarations but through the quiet accumulation of lived difference.

This identity shift has material consequences. Taiwan’s bubble tea nationalism—the fierce defense of the drink’s Taiwanese origins against mainland appropriation—reveals something deeper than consumer pride. It demonstrates that Taiwanese identity now requires active differentiation from China. The two societies have diverged so fundamentally that even shared cultural products become contested terrain.

Language accelerates the divide. Taiwan’s romanization systems for Hokkien create orthographic divergence from mainland Minnan standardization. What was once an oral dialect continuum is becoming incompatible written systems. Taiwanese opera performers trained in local traditions cannot seamlessly collaborate with mainland counterparts. The linguistic infrastructure of shared culture is fraying.

Most significant is Taiwan’s adoption of a settler-colonial framework to understand its own history. By positioning Han Taiwanese as settlers requiring reconciliation with indigenous peoples, Taiwan has created an identity structure that is ontologically incompatible with Beijing’s unification discourse. You cannot simultaneously acknowledge that your ancestors colonized Taiwan and accept that Taiwan was always part of China. The frameworks are mutually exclusive.

Beijing’s response—economic inducements, cultural exchanges, political pressure—has failed to reverse these trends. The sixteen financial integration measures rolled out for Fujian-Taiwan banking in 2025 create infrastructure for tracking remittance sentiment, but they cannot manufacture the sentiment itself. Money flows where identity permits. Identity no longer permits.

The Semiconductor Paradox

If identity is the soft constraint, semiconductors are the hard one.

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company produces over ninety percent of the world’s most advanced chips. This concentration is not accidental. It reflects decades of investment, accumulated expertise, and network effects that cannot be replicated quickly. TSMC’s fabs represent the most sophisticated manufacturing operations in human history. The cleanroom purity protocols alone—bunny suits, particle control measured in parts per billion—constitute a form of industrial priesthood that takes years to master.

This gives Taiwan extraordinary leverage. A Chinese invasion that damaged TSMC’s facilities would crash the global economy. Every smartphone, every data center, every advanced weapons system depends on chips that flow through a single island. Taiwan has, whether intentionally or not, made itself too important to lose.

But leverage is not safety. The same concentration that protects Taiwan also makes it a target. Beijing’s strategic planners understand that controlling TSMC would give China dominance over the commanding heights of the twenty-first-century economy. The prize is worth enormous risk.

Here is the paradox: Western efforts to reduce semiconductor dependence on Taiwan are simultaneously strengthening and weakening the island’s position. TSMC’s Arizona expansion, Samsung’s Texas investments, Intel’s Ohio fabs—all represent attempts to diversify supply chains away from cross-strait risk. If these efforts succeed, Taiwan loses its silicon shield. The strategic value of the island declines. Beijing’s cost-benefit calculation shifts.

This creates a closing window, but not the one most analysts describe. The window is not for invasion. It is for Taiwan’s irreplaceability. Every quarter that Western semiconductor capacity expands, Taiwan’s leverage diminishes. Every year that passes without conflict, the argument for conflict weakens—but so does the argument for defending Taiwan at any cost.

Beijing watches these timelines carefully. The question is not whether China can invade before Western fabs come online. The question is whether Taiwan’s strategic value will decline enough that the international response to coercion becomes manageable.

The American Ambiguity

Washington’s position has been strategically ambiguous for fifty years. The policy worked because all parties understood its logic: the United States would not support Taiwanese independence, but it would not accept Chinese coercion. Taiwan would not declare independence. China would not use force. Everyone could pretend the status quo was temporary while treating it as permanent.

This equilibrium is breaking down.

American ambiguity depends on credibility in both directions—credible commitment to defend Taiwan, credible restraint on Taiwanese adventurism. Recent years have eroded both. Congressional visits to Taipei, arms sales, rhetorical escalation—all signal commitment but also provocation. Beijing interprets each gesture as evidence that America is abandoning ambiguity for containment. The more Washington signals resolve, the more Beijing concludes that time is not on its side.

The alliance structure compounds the problem. American commitment to Taiwan is entangled with commitments to Japan, South Korea, Australia, and the Philippines. Credibility is fungible. If Washington fails to defend Taiwan, every ally questions American guarantees. If Washington defends Taiwan, it risks war with a nuclear power while simultaneously depleting resources needed for other contingencies.

The mathematics of alliance credibility create a resource dilution trap. Extended deterrence against North Korea cannot address Taiwan contingencies. Forces positioned for one scenario are unavailable for another. The Pacific is large. American capacity is finite.

Most troubling is the moral hazard inversion. Conventional alliance theory predicts that security guarantees reduce a client’s willingness to self-defend—why invest in your own military if the patron will protect you? Taiwan inverts this logic. Survey data consistently shows that belief in American intervention increases Taiwanese willingness to fight. The guarantee does not substitute for self-defense; it enables it.

This creates a dependency trap. Taiwanese fighting will depends partly on confidence in American support. American support depends partly on evidence of Taiwanese resolve. Each side waits for the other to demonstrate commitment first. The system is stable until it isn’t.

The Grey Zone Grind

War is not the only path to reunification. Beijing has alternatives.

Grey zone operations—military exercises, airspace incursions, coast guard harassment, economic pressure—impose costs without triggering alliance responses. The goal is not conquest but exhaustion. Make Taiwan’s position so uncomfortable, so expensive, so isolated that the status quo becomes untenable.

The strategy has logic. Taiwan’s military must respond to every incursion, every exercise, every probe. This depletes readiness, strains personnel, consumes budgets. China’s resources are larger. It can sustain the pressure longer. The cost-exchange ratio favors the aggressor.

Information operations amplify the effect. Disinformation campaigns, media manipulation, political interference—all designed to polarize Taiwanese society, undermine confidence in institutions, make governance harder. The goal is not to win hearts but to exhaust minds.

Submarine cable vulnerabilities add another dimension. The hundred-mile anchor drag incidents affecting Baltic cables—Sweden-Lithuania, Germany-Finland—demonstrate that infrastructure can be severed with plausible deniability. Taiwan’s internet connectivity depends on undersea cables. Disruption would isolate the island without firing a shot.

The grey zone strategy has limits. It has not reversed Taiwanese identity trends. It has not weakened the US-Taiwan relationship. It may even be counterproductive—each Chinese provocation reinforces Taiwanese distinctiveness and international sympathy. But it imposes costs. And costs compound.

The Scenarios Nobody Wants

Project forward five years. What breaks first?

Scenario one: Frozen status quo. The most likely outcome is continued stalemate. Beijing maintains pressure without escalating to war. Taiwan maintains defense without declaring independence. Washington maintains ambiguity without clarifying commitment. Everyone is unhappy. No one changes position. The system holds through inertia.

This scenario requires nothing to change. It is the default. But defaults erode. Each year, Taiwanese identity consolidates further. Each year, Chinese military capability improves. Each year, American attention fragments across competing priorities. The status quo is not static. It is slowly tilting.

Scenario two: Economic strangulation. Beijing concludes that military invasion is too costly but economic coercion is not. A blockade—declared or undeclared—restricts Taiwan’s trade. Energy imports cease. Semiconductor exports halt. The global economy convulses, but China bets that international pressure falls on Taiwan to negotiate rather than on China to relent.

This scenario tests whether Taiwan’s silicon shield works in reverse. If the world needs Taiwanese chips, will it accept Chinese terms to restore supply? Or will it organize to break the blockade? The answer depends on variables no one can predict—American presidential politics, European energy dependence, Japanese constitutional constraints.

Scenario three: Accidental escalation. A pilot misjudges. A ship collides. A missile test goes wrong. Neither side wants war, but neither side can back down. Escalation dynamics take over. The conflict that nobody planned becomes the conflict that nobody can stop.

This scenario is less likely than analysts fear but more dangerous than policymakers admit. The Taiwan Strait is crowded with military assets operating in close proximity under ambiguous rules of engagement. Accidents are possible. Miscalculation is possible. The system has no circuit breakers.

Scenario four: Negotiated accommodation. Some future Taiwanese government, exhausted by pressure and skeptical of American commitment, opens talks with Beijing. Not reunification—something less. Confederation. Special status. A Hong Kong model with better guarantees.

This scenario requires Beijing to offer terms Taiwan can accept and Taiwan to trust Beijing to honor them. After Hong Kong, that trust does not exist. The one country, two systems model is dead. Beijing killed it. No Taiwanese politician can sell a deal that looks like surrender, and no deal Beijing would accept looks like anything else.

The Intervention Points

Where does leverage exist?

First, semiconductor diversification must be managed, not maximized. The West needs supply chain resilience, but complete independence from Taiwan removes Taiwan’s strategic value. The optimal policy maintains enough concentration to preserve Taiwan’s importance while building enough redundancy to survive disruption. This is a narrow target. Policymakers are not aiming for it. They are aiming for maximum diversification, which may be strategically counterproductive.

Second, Taiwan must invest in asymmetric defense that makes invasion costly without relying on American intervention. Drones, mines, mobile missiles, civil defense—capabilities that impose attrition rather than seeking decisive battle. The cost-exchange ratio of drone warfare favors defenders who can produce cheap systems faster than attackers can destroy them. Taiwan has begun this shift. It must accelerate.

Third, the United States must clarify its commitment without abandoning ambiguity entirely. This sounds contradictory. It is not. Washington can specify what it will do in response to specific Chinese actions—blockade, bombardment, invasion—without specifying what it will do in response to Taiwanese provocations. Asymmetric clarity deters Beijing while restraining Taipei.

Fourth, regional allies must coordinate. Japan, Australia, South Korea, the Philippines—all have stakes in Taiwan’s status. None can defend Taiwan alone. All can contribute to deterrence collectively. The multiplication of actors complicates Chinese planning and distributes costs. ASEAN’s studied neutrality may be durable, but the first island chain’s commitment need not depend on it.

Each intervention has costs. Semiconductor diversification is expensive and slow. Asymmetric defense requires abandoning prestige platforms. Clarified commitment risks entrapment. Allied coordination requires trust that does not yet exist. There are no free moves.

The Long Game

Reunification is not a trajectory. It is an aspiration colliding with constraints.

Beijing wants Taiwan. It cannot take Taiwan without unacceptable risk. It cannot abandon the claim without unacceptable cost. So it waits, pressures, probes—hoping that time will deliver what force cannot.

Taiwan wants independence in fact if not in name. It cannot declare independence without triggering the war it seeks to avoid. It cannot accept reunification without betraying the identity its people have built. So it maintains the fiction of the status quo while the substance changes beneath it.

Washington wants stability. It cannot guarantee stability without commitments that risk war. It cannot abandon commitments without guaranteeing instability. So it hedges, signals, deploys—hoping that deterrence holds while the balance shifts.

The system is stable because all parties fear the alternatives more than they desire their objectives. This is not peace. It is paralysis. Paralysis can last a long time. It can also end suddenly.

The trajectory of China-Taiwan relations is not toward reunification or independence or war. It is toward a moment when the constraints that have held for seventy-five years no longer hold. No one knows when that moment comes. No one knows what triggers it. Everyone knows it is closer than it was.

Taiwan will remain almost. Until it isn’t.