The Arsenal Paradox

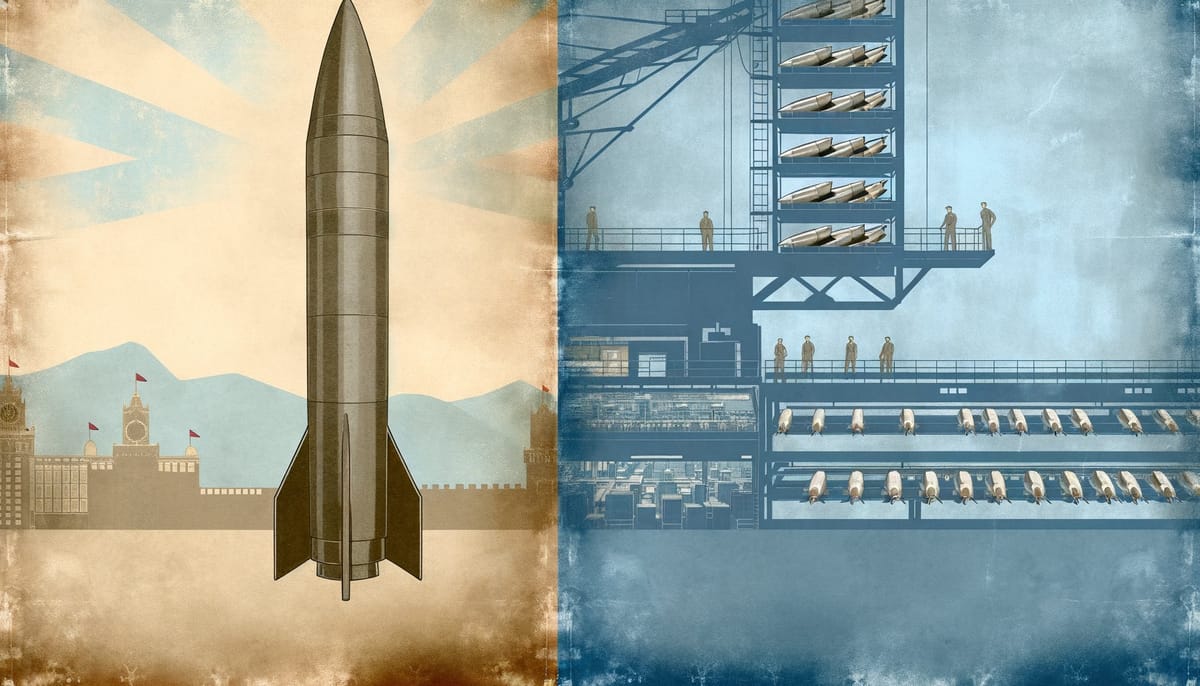

The next global conflict will be decided not by battlefield technology but by industrial architecture—the ability to produce weapons at scale while economies continue functioning. The United States is losing this race before the shooting starts.

The Arsenal Paradox

The United States lost its last classified war game against China. Not narrowly—comprehensively. The defeat had nothing to do with tactics, doctrine, or the courage of simulated forces. America ran out of missiles.

This is not a readiness problem. It is an architecture problem. The U.S. military has spent three decades perfecting exquisite weapons—systems so sophisticated they take years to build and cost millions per unit. China has spent the same period building factories. When the shooting starts, the side that can replenish its arsenals at scale wins. The side that cannot loses, no matter how advanced its technology.

The question of which military technologies will define the next global conflict is thus the wrong question. The right question is: which nations can field decisive technologies in conflict-relevant quantities before their economies collapse or their political will breaks? Technology divorced from industrial capacity is performance art. What matters is the synthesis of innovation and production—the ability to move from prototype to mass deployment while your society still functions.

This reveals an uncomfortable truth: the most important military technology is not a weapon system at all. It is the industrial architecture that determines how many weapon systems you can build, how quickly you can replace losses, and whether your supply chains survive contact with the enemy. The wars of the next decade will be won in factories, not laboratories.

The Velocity Trap

Modern Western defense procurement operates on a twenty-year cycle. The F-35 program launched in 2001; full-rate production began in 2019. The Columbia-class ballistic missile submarine started development in 2007; the first boat will enter service in 2031. These timelines assume peace—that adversaries will politely wait while new capabilities move through development, testing, and low-rate initial production.

They will not wait.

China’s rare earth supply chain runs from mining through magnet fabrication in a vertically integrated system that took thirty years to build. The United States imports 80% of its rare earth elements and has no domestic capacity to process them into the permanent magnets required for hypersonic missiles, advanced radar, and precision-guided munitions. When Taiwan’s TSMC stops shipping chips or China restricts rare earth exports, American weapons production doesn’t slow—it stops.

This is not hypothetical. During the Ukraine conflict, the United States discovered it could produce 240,000 artillery shells annually. Ukraine was firing 6,000 rounds per day. Russia was firing 20,000. The arithmetic is brutal: forty days of Ukrainian consumption exceeded America’s entire annual production. Scaling production required rebuilding supply chains, training workers, and reactivating facilities that had been shuttered for decades. The timeline for meaningful increases? Eighteen months minimum.

The velocity trap operates at every level. Javelin anti-tank missiles take thirty-two months from order to delivery. HIMARS rockets: twenty-four months. Patriot interceptors: thirty-six months. These are not development timelines—these are production timelines for mature, proven systems. A conflict that consumes munitions faster than industry can replace them becomes a war of attrition where the side with larger starting inventories wins by default.

This inverts the traditional calculus of military technology. The “best” weapon is not the most capable—it is the one you can field in sufficient numbers to matter. A thousand good-enough drones defeat ten exquisite fighters when the fighters run out of missiles and the drones keep coming.

The Swarm Revolution

Ukraine’s use of commercial quadcopters modified with grenades reveals the signature military innovation of this decade: attritable mass defeats exquisite precision. A $500 drone carrying a $50 grenade can mission-kill a $5 million tank. The economics are devastating. Even if the tank’s active protection system works perfectly, destroying twenty drones costs more than the tank is worth.

This is not about drones specifically. It is about the industrialization of military effects through cheap, expendable systems that can be produced at commercial scale. The United States’ Replicator initiative aims to field thousands of autonomous systems within two years—a timeline that would be impossible for traditional defense procurement but is achievable precisely because it leverages commercial manufacturing.

The swarm revolution rests on three technological foundations: commercial sensor miniaturization, AI-enabled autonomy, and mesh networking. None of these are cutting-edge military technologies. They are mature commercial capabilities being weaponized at scale. A $2,000 drone with a $200 AI chip running open-source computer vision can identify and track vehicles as effectively as systems costing a hundred times more.

But—and this matters—swarms are not wonder weapons. They are vulnerable to electronic warfare, require constant operator oversight despite “autonomy,” and face the same munitions exhaustion problem as traditional forces. A swarm of a thousand drones is useless if you cannot produce another thousand to replace losses. The advantage goes not to whoever deploys swarms first but to whoever can sustain swarm production throughout a protracted conflict.

This creates a new form of arms race: not who has the most advanced technology, but who can mobilize industrial capacity fastest. China produces 90% of the world’s commercial drones. DJI alone manufactures millions of units annually. The United States produces fewer than 100,000 military drones per year across all types. In a conflict requiring mass drone employment, America would need to either seize Chinese manufacturing capacity (impossible) or build entirely new production lines (years, not months).

The same logic applies to loitering munitions, uncrewed surface vessels, and autonomous ground vehicles. These systems work not because they are sophisticated but because they are numerous. Sophistication without scale is a museum piece.

The Invisible War

Cyber operations and electronic warfare do not destroy enemy forces—they destroy enemy knowledge. A tank with a jammed GPS, spoofed communications, and disabled fire control system is not a tank. It is thirty tons of immobile metal. The defining characteristic of modern warfare is not kinetic destruction but epistemological collapse: the progressive inability to know where you are, where the enemy is, or whether your weapons will function when needed.

GPS spoofing has already grounded civilian aircraft, disrupted shipping, and caused navigation failures across conflict zones. Military systems are more hardened but operate on the same fundamental architecture: they trust timing signals from satellites they cannot verify. Spoofing GPS time forward by even microseconds creates cascading failures in weapons systems, communications networks, and logistics tracking. The system cannot “go back” to correct time—once spoofed forward, it remains permanently desynchronized until manually reset.

This creates asymmetric advantages for defenders. China’s A2/AD (anti-access/area denial) strategy does not require destroying American carrier groups—it requires making the battlespace illegible. If U.S. forces cannot trust their navigation, cannot communicate securely, and cannot verify targeting data, they cannot operate effectively even if their platforms remain physically intact.

The counter-argument is that the United States possesses overwhelming cyber capabilities through organizations like NSA’s Tailored Access Operations. True. But TAO’s power derives from bespoke customization—each operation requires specialized tools coded for specific targets. This is the opposite of industrial scale. TAO can compromise a hundred high-value systems. It cannot compromise ten thousand low-value systems simultaneously. Mass defeats precision here too.

The deeper problem is that cyber and electronic warfare capabilities are inherently dual-use and difficult to attribute. A GPS spoofing attack could come from a state actor, a proxy force, or a criminal organization. This attribution problem creates escalation risks: if you cannot identify the attacker, you cannot calibrate your response. Overreaction triggers wider conflict; underreaction invites further attacks.

Meanwhile, the electromagnetic spectrum becomes progressively more contested. Electronic warfare systems that once provided decisive advantages now face adaptive adversaries who cycle through frequencies, use directional antennas, and employ AI-driven counter-countermeasures. The EW advantage lasts months, not years. Sustaining it requires continuous development and deployment of new systems—another industrial capacity challenge.

The Deterrence Dilemma

Nuclear weapons remain the ultimate backstop. No conventional military technology changes the fundamental calculus: escalation to nuclear use ends conflicts by making victory meaningless. But nuclear modernization programs reveal the same industrial architecture problem that plagues conventional forces.

The United States plans to spend $1.5 trillion over thirty years modernizing its nuclear triad. This is not $1.5 trillion in new capability—it is $1.5 trillion to maintain current capability as Cold War-era systems age out. The B-52 bombers that will carry new Long-Range Standoff weapons entered service in 1955. They will remain in service until 2050. This is not a sign of excellent design; it is a sign that building new bombers at scale is prohibitively expensive.

Russia’s nuclear modernization follows a different path: accepting lower reliability in exchange for higher numbers. The Poseidon nuclear-powered torpedo and Burevestnik nuclear-powered cruise missile are not precision instruments. They are systems designed to be produced in quantity despite uncertain performance. This is rational: in nuclear war, reliability matters less than numbers. Ten warheads with 70% reliability deliver more expected damage than five warheads with 95% reliability.

China’s nuclear expansion—from 200 warheads to potentially 1,500 by 2035—represents a third model: rapid buildup from a small base using industrial capacity developed for civilian purposes. China’s missile production infrastructure, rare earth processing, and precision manufacturing were all built for commercial applications. Weaponizing them is a matter of political decision, not industrial capability.

The deterrence dilemma is that nuclear weapons prevent great power war only if all parties believe they would actually be used. But the threshold for nuclear use rises with every conventional capability that promises to achieve objectives without escalation. Hypersonic missiles, cyber attacks, and drone swarms all create options that are “just below” nuclear use. This proliferation of sub-nuclear options makes deterrence more fragile, not more stable.

Worse, emerging technologies blur the line between conventional and nuclear. A hypersonic missile could carry either warhead type. A cyber attack could disable early warning systems, making nuclear forces vulnerable. Space-based sensors could provide targeting data for both conventional precision strikes and nuclear weapons. The distinction between “conventional” and “nuclear” war becomes meaningless when the same platforms deliver both effects.

The Substrate Wars

Beneath every weapon system lies a supply chain. Hypersonic missiles require rare earth magnets. AI targeting systems require advanced semiconductors. Electronic warfare pods require gallium nitride amplifiers. These materials do not appear spontaneously—they emerge from mining, refining, and manufacturing processes that take decades to build and are concentrated in a handful of nations.

China controls 60% of rare earth mining and 90% of rare earth processing. Taiwan’s TSMC produces 90% of advanced logic chips below 10nm. The Netherlands’ ASML holds a monopoly on extreme ultraviolet lithography machines required for cutting-edge semiconductor production. These are not diversified, resilient supply chains. They are single points of failure.

The United States has attempted to reshore semiconductor production through the CHIPS Act, rare earth processing through Defense Production Act investments, and general supply chain resilience through ally coordination. These efforts will take a decade to mature—if they succeed at all. Building a semiconductor fab costs $20 billion and requires three years. Training the specialized workforce requires longer. Developing rare earth processing that does not create environmental disasters requires solving chemistry problems that China spent thirty years working through.

Meanwhile, China has spent the same period integrating its supply chains vertically. Rare earth mines feed processing facilities that feed magnet manufacturers that feed weapons producers—all within a command economy that can prioritize military production over civilian consumption. When conflict starts, China can surge weapons production by redirecting existing capacity. The United States must first build the capacity, then surge it.

This is the substrate war: control over the raw materials, processing capabilities, and manufacturing infrastructure that determine who can build weapons at scale. It is being fought now, in peacetime, through export controls, investment restrictions, and industrial policy. The side that wins the substrate war before shooting starts has already won the shooting war.

The lithium example is instructive. Electric vehicle batteries and advanced military systems both require lithium-ion cells. China controls 70% of global lithium refining and 60% of battery cell production. A conflict that disrupts Chinese lithium exports would simultaneously cripple Western EV production and military electronics manufacturing. This is not a vulnerability that can be fixed quickly—building alternative supply chains requires mining rights, environmental permits, processing facilities, and manufacturing expertise that take years to assemble.

The same logic applies to every critical material: cobalt for batteries, tungsten for armor-piercing rounds, titanium for airframes, graphite for electronics. The nation that controls these substrates controls the pace of weapons production. Technology is irrelevant if you cannot source the materials to build it.

The Doctrine Graveyard

Military organizations prepare for the last war while insisting they are preparing for the next one. The United States’ Multi-Domain Operations doctrine envisions seamlessly coordinated effects across land, sea, air, space, and cyber domains. This requires communications networks that work under electronic attack, commanders who can process information faster than adversaries can disrupt it, and units that can execute complex maneuvers while under fire.

None of these requirements survive contact with reality. Communications networks are the first target in any conflict. Commanders cannot process information they do not trust. Units cannot execute complex maneuvers when GPS is spoofed and radios are jammed. The doctrine assumes a level of battlespace transparency that modern EW and cyber capabilities make impossible.

The Russian military’s experience in Ukraine is instructive. Russia entered the conflict with sophisticated doctrine emphasizing combined arms operations, electronic warfare superiority, and precision strike. Within weeks, this collapsed into artillery-heavy attrition warfare because Ukrainian EW denied Russian forces the communications and navigation required for complex operations. Doctrine became irrelevant when the technological assumptions underlying it proved false.

China’s doctrine emphasizes “systems destruction warfare”—targeting not individual platforms but the networks that enable them to function. Destroy satellite communications and air defense systems cannot coordinate. Disrupt logistics networks and forward units run out of fuel. Compromise command systems and forces cannot receive orders. This is doctrine designed around the assumption that modern militaries are fragile networks, not resilient hierarchies.

The United States’ doctrine assumes the opposite: that American technological superiority will provide battlespace awareness that adversaries lack. This assumption is a decade out of date. Commercial satellites provide near-real-time imagery to anyone with an internet connection. AI-enabled analysis tools can process this imagery faster than human analysts. The information advantage that once required billion-dollar systems now costs thousands of dollars.

What remains is not a technology gap but a decision-making gap. The side that can translate information into action faster wins. This is not about AI-enabled decision support—it is about organizational structures that empower low-level commanders to act without waiting for higher approval. The U.S. military’s hierarchical command culture is fundamentally mismatched to the tempo of modern warfare.

The Mobilization Problem

The United States has not mobilized its industrial base for war since 1945. The infrastructure for doing so—government-owned factories, surge production capacity, trained reserve workforce—has been systematically dismantled in favor of lean, just-in-time commercial manufacturing. This was rational in peacetime. It is catastrophic in war.

Mobilization is not about flipping a switch. It requires legal authorities to redirect civilian production, financial mechanisms to compensate companies for retooling, and workforce training to build complex weapons. The Defense Production Act provides legal authority but no funding. The defense industrial base consists of a handful of prime contractors with limited surge capacity and supply chains that depend on foreign sources for critical components.

Historical precedent is sobering. U.S. tank production in World War II peaked at 2,000 per month. Current production is fifteen per month. Artillery shell production in WWII exceeded 1 million per month. Current production is 20,000 per month. The gap is not just quantitative—it is qualitative. The workforce that built WWII weapons is dead. The factories that produced them are demolished. The supply chains that fed them are gone.

Rebuilding this capacity requires more than money. It requires a political decision to prioritize military production over civilian consumption—to accept inflation, shortages, and economic disruption in exchange for weapons production. No Western democracy has demonstrated willingness to make this choice in peacetime. Whether they would make it in wartime is an open question.

China faces no such constraint. Its command economy can redirect production by decree. Civilian factories producing commercial drones can produce military drones overnight. Electronics manufacturers can switch from smartphones to weapons systems. The workforce is already trained. The supply chains are already integrated. Mobilization is not a transformation—it is a reallocation.

This creates a fundamental asymmetry: China can mobilize faster than the United States can recognize the need to mobilize. By the time Western democracies build political consensus for economic sacrifice, China will have surged production to levels that cannot be matched. The war will be decided in the first six months, before American industrial mobilization can matter.

The Convergence

Three technologies are converging to create a new warfare paradigm: AI-enabled autonomy, hypersonic strike, and integrated air defense. Individually, each is evolutionary. Together, they are revolutionary.

AI-enabled autonomy allows weapons to operate in communications-denied environments. A missile that can find and engage targets without human input does not care if GPS is spoofed or communications are jammed. It continues to function when traditional systems fail. This is not artificial general intelligence—it is narrow AI trained on specific tasks. But narrow AI is sufficient for target recognition, path planning, and engagement decisions.

Hypersonic weapons compress decision timelines to minutes. A hypersonic glide vehicle launched from 2,000 kilometers away reaches its target in under ten minutes. This is faster than human decision-making processes can respond. By the time commanders recognize an attack, assess options, and issue orders, the weapons have already struck. Defense becomes impossible without automated systems that can detect, decide, and engage without human authorization.

Integrated air defense ties these together. Modern IADS combine long-range surveillance radars, networked missile batteries, and AI-enabled battle management. They create overlapping coverage zones where no aircraft can operate safely. The only way to defeat them is through saturation—launching more weapons than the defense can engage. This returns warfare to arithmetic: whoever can launch more missiles wins.

The convergence of these technologies creates a new strategic reality: the offense-defense balance tips decisively toward offense. A nation that strikes first can destroy enough enemy capability that retaliation becomes impossible. This creates incentives for preemption that are fundamentally destabilizing. When leaders believe that striking first is the only way to avoid being struck first, crisis stability collapses.

The technical counter is resilience through distribution—spreading capabilities across enough platforms that no first strike can be decisive. But distribution requires numbers, and numbers require industrial capacity. The same capacity problem that plagues every other aspect of modern warfare.

The Endgame

The next global conflict will be decided by industrial architecture, not battlefield technology. The side that can produce munitions, platforms, and critical components at scale while its economy continues functioning will win. The side that exhausts its arsenals and cannot replenish them will lose, regardless of how sophisticated its weapons are.

This is not a prediction—it is a mathematical certainty. Modern weapons are consumed faster than they can be replaced. Supply chains are fragile and concentrated in adversary nations. Mobilization infrastructure has been dismantled and cannot be rebuilt quickly. The side that enters conflict with larger inventories and greater production capacity has already won.

The United States is not that side.

China controls the substrates, commands the supply chains, and can mobilize industrial capacity at speeds that Western democracies cannot match. American technological superiority matters only if it can be fielded in conflict-relevant quantities. It cannot. The F-35 is an engineering marvel. It is also produced at seventy units per year. China produces 200 fourth-generation fighters annually and is ramping up fifth-generation production. Quality matters. Quantity matters more.

The path forward requires choices that no Western democracy has been willing to make: accepting higher defense spending, rebuilding domestic supply chains, maintaining surge production capacity, and prioritizing military readiness over economic efficiency. These choices are expensive, politically unpopular, and economically disruptive. They are also necessary.

The alternative is losing the next war before it starts—not on the battlefield, but in the factories, mines, and supply chains that determine who can sustain combat operations and who cannot. Military technology is irrelevant without the industrial capacity to produce it at scale. The nation that learns this lesson first wins. The nation that learns it second becomes a historical footnote.

The arsenal paradox is this: the most advanced military in history cannot produce enough weapons to fight the war it has prepared for. Technology without industrial capacity is performance art. The next global conflict will be won by whoever solves this problem first. Current trajectories suggest it will not be the West.