Taiwan's submarine gamble: Can eight boats deter a Chinese invasion?

Taiwan is building its first indigenous submarines after decades of failed foreign procurement. The program aims to create sea denial capability against China, but faces a race between slow production schedules and rapidly improving Chinese anti-submarine warfare. The window where these boats...

🎧 Listen to this article

The Phantom Fleet

Taiwan launched its first indigenous submarine in September 2023 with considerable fanfare. The Hai Kun—named after a mythical sea creature—slipped into the waters of Kaohsiung harbor as President Tsai Ing-wen declared a “historic milestone.” The ceremony marked the end of a 30-year quest to build submarines domestically after every foreign supplier bowed to Chinese pressure. But the celebration obscured a harder question: can eight diesel-electric boats, delivered over the next decade, actually deny the Taiwan Strait to a Chinese invasion fleet?

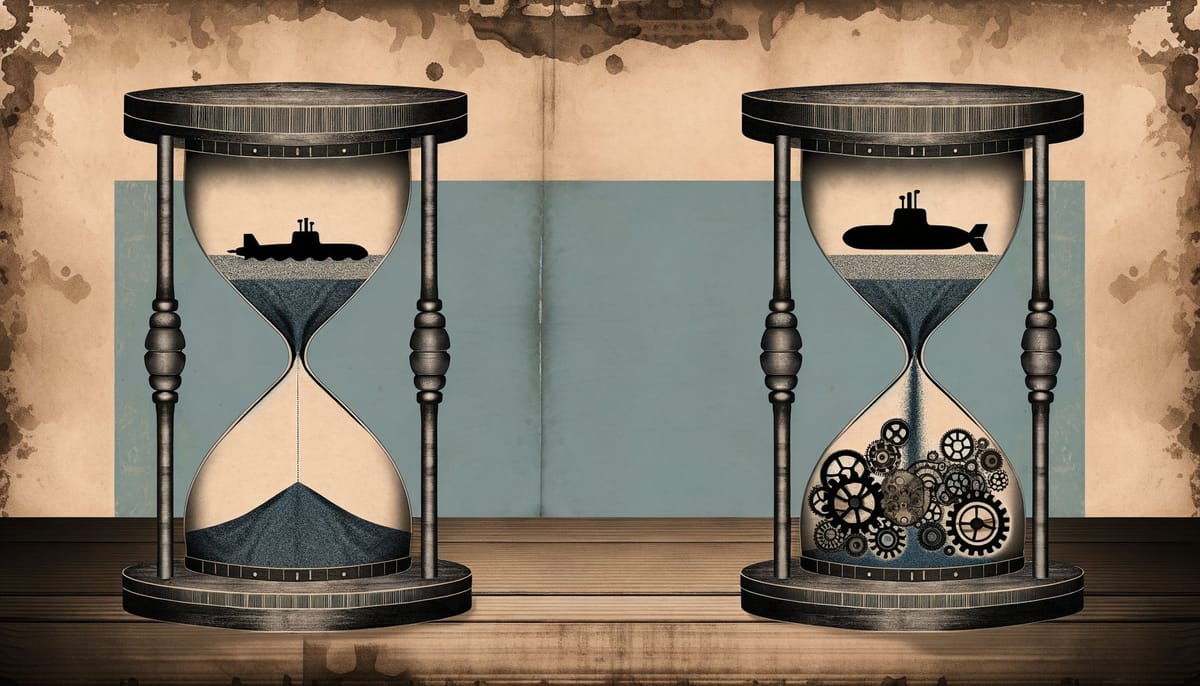

The answer depends less on the submarines themselves than on a race between two clocks. One measures Taiwan’s halting industrial progress—delays, technical setbacks, the painstaking accumulation of undersea warfare expertise. The other tracks China’s anti-submarine warfare capabilities, which are improving faster than most Western analysts expected. The window where Taiwan’s submarines could matter is neither permanently open nor irrevocably closed. It is narrowing.

What Sea Denial Actually Means

Sea denial is not sea control. A navy practicing sea denial does not need to dominate the ocean; it needs only to make the ocean unusable for an adversary. Admiral Stansfield Turner called it “guerrilla warfare at sea”—hitting and running, forcing the enemy to expend disproportionate resources protecting every convoy, every landing ship, every logistics vessel.

For Taiwan, this concept has particular appeal. The island cannot hope to match China’s surface fleet, which now exceeds 370 vessels. But submarines operate by different rules. A single boat lurking in the Taiwan Strait forces an invasion fleet to conduct time-intensive anti-submarine sweeps before every crossing. Even if the submarine never fires a torpedo, its potential presence imposes delay. Delay compounds. Amphibious operations require precise timing—tides, weather, troop readiness all must align. Every hour spent hunting submarines is an hour Taiwan’s defenders use to reinforce beaches, reposition missiles, or wait for American intervention.

The strategic logic is elegant. The operational reality is messier.

Taiwan currently operates four submarines. Two are museum pieces: the Hai Shih and Hai Pao, built during World War II for the US Navy, transferred to Taiwan in the 1970s, and now used solely for training. The other two—the Hai Lung and Hai Hu—are Dutch-built boats from the 1980s, modernized but aging. They represent Taiwan’s entire combat-capable undersea force.

The Indigenous Defense Submarine program aims to change this arithmetic. Eight new boats, the first already launched, with the remainder scheduled for delivery by 2038. Each will displace roughly 2,500 tons, carry heavyweight torpedoes and Harpoon anti-ship missiles, and incorporate technology from multiple foreign sources—American combat systems, European propulsion components, undisclosed assistance from Japan and other allies who prefer not to be named.

Eight boats sounds modest. It is. But submarine math works differently than surface ship math. Boats require maintenance cycles; at any given time, perhaps three or four might be operationally available. Against China’s submarine fleet of approximately 70 vessels—including nuclear attack boats that Taiwan cannot match—the numbers look grim.

Yet numbers alone mislead. The question is not whether Taiwan can win an undersea war. It cannot. The question is whether Taiwan can impose costs high enough to complicate Chinese planning, delay invasion timelines, and create uncertainty in Beijing’s calculations. This is a lower bar. It may still be too high.

The Acoustic Labyrinth

The Taiwan Strait presents one of the most acoustically challenging environments on Earth. Shallow waters—averaging 60 meters deep, with some areas under 40 meters—create a reverberant nightmare for sonar operators. Sound bounces off the seafloor, the surface, and the thermoclines in between. The Holocene sediments discharged by Chinese rivers add another layer of complexity: young, unconsolidated material that scatters acoustic energy unpredictably.

For Taiwan’s submarines, this environment offers both danger and opportunity. Shallow water makes submarines easier to detect from aircraft—magnetic anomaly detectors and dipping sonars can cover the water column quickly. But it also degrades the performance of hull-mounted sonars on surface ships and submarines alike. A diesel-electric boat running on batteries, creeping along the bottom at three knots, becomes extraordinarily difficult to localize. The noise of a 300-ship invasion fleet would further mask submarine signatures.

China knows this. The People’s Liberation Army Navy has invested heavily in anti-submarine warfare, but according to the US Department of Defense’s 2024 annual report, “it continues to lack a robust deep-water ASW capability.” The assessment is more nuanced than it appears. China’s weakness lies in blue-water operations—tracking American nuclear submarines in the open Pacific. In the confined waters of the Taiwan Strait, where distances are short and aircraft can saturate an area with sonobuoys, the balance shifts.

The PLAN has deployed Type 927 ocean surveillance ships, KQ-200 maritime patrol aircraft based on the Y-8 transport, and Z-20F helicopters equipped with dipping sonars and torpedoes. A China Maritime Report from the US Naval War College notes that “the PLAN clearly views fixed-wing and vertical lift ASW capabilities as a crucial component necessary for any of its amphibious based contingencies.” The doctrine is sound. The execution remains uneven.

Chinese sonar technology, by most Western assessments, lags American and NATO systems by one to two generations. Sonobuoys are less sophisticated; signal processing is less refined. But technology gaps close. Moore’s Law applies to signal processing as surely as it applies to smartphones. China’s defense budget allows sustained investment in exactly the areas where it trails.

The more troubling development is China’s undersea surveillance network—sometimes called the “Underwater Great Wall.” Fixed sensors on the seabed, networked to shore-based processing centers, could provide persistent coverage of likely submarine patrol areas. The system’s actual capabilities remain classified, but its existence changes the calculus. A submarine that must evade not only active hunting but also passive detection grids faces a fundamentally different problem.

The Production Race

Taiwan’s submarine program has suffered delays. The Hai Kun was launched in 2023 but will not achieve operational capability until 2025 at the earliest. Combat system integration—always the hardest part—has proven more difficult than anticipated. The second boat is under construction; subsequent hulls depend on lessons learned from the first.

CSBC Corporation, Taiwan’s state-owned shipbuilder, had never built a submarine before this program. The learning curve is steep. Submarine construction requires tolerances measured in millimeters, welding techniques that take years to master, and quality control systems that commercial shipbuilding does not demand. CSBC has imported expertise where it can, but institutional knowledge accumulates slowly.

The optimistic scenario: Taiwan commissions one boat per year starting in 2026, achieving a fleet of eight operational submarines by the early 2030s. The realistic scenario: production slips, technical problems emerge, and the full fleet arrives closer to 2038. The pessimistic scenario: cost overruns and political shifts slow the program further, leaving Taiwan with three or four boats when it needs eight.

Meanwhile, China’s ASW capabilities improve on a more predictable schedule. The PLAN commissions new surface combatants with integrated ASW systems. Maritime patrol aircraft accumulate flight hours and operational experience. The undersea surveillance network expands. Each year of Taiwanese delay narrows the window where submarines might matter.

This temporal asymmetry defines the strategic problem. Taiwan’s program operates on what might be called bureaucratic time—budget cycles, procurement delays, technical setbacks, political transitions every four years. China operates on what its planners call “national rejuvenation” time—a generational project with consistent funding and centralized direction. The two clocks tick at different speeds.

The Fleet-in-Being

There is a strategic concept that might save Taiwan’s submarine program from irrelevance: the fleet-in-being. The term dates to the 17th century, when an English admiral kept his ships in port rather than risk them against a superior French fleet. The mere existence of those ships—their potential to sortie at any moment—forced the French to maintain blockading forces, diverted resources, and constrained options.

Taiwan’s submarines need not sink Chinese ships to matter. They need only exist, and be believed capable of sinking Chinese ships. An invasion fleet that must assume submarines lurk in the Strait will move more slowly, protect itself more heavily, and accept greater risk. The psychological burden falls on the attacker.

This logic has limits. A fleet-in-being works only if the adversary believes the fleet might actually act. If China concludes that Taiwan’s submarines are too few, too poorly maintained, or too easily neutralized, the deterrent effect evaporates. Credibility requires demonstrated capability—exercises, occasional shows of force, evidence that crews are trained and boats are operational.

Taiwan’s navy understands this. Recent exercises have emphasized submarine operations, and the service has worked to improve crew proficiency on the existing Hai Lung-class boats. But proficiency on 1980s-vintage submarines does not automatically transfer to new platforms with different systems. The IDS boats will require years of operational experience before they achieve full effectiveness.

The deeper problem is doctrinal. Taiwan’s navy has historically focused on surface warfare and anti-surface operations. Submarine culture—the particular mindset required for undersea combat—takes a generation to develop. American submarine officers speak of “the silent service” with something approaching religious reverence. That institutional identity shapes everything from training to tactics to maintenance standards. Taiwan cannot import it; the culture must grow organically.

Integration Failures

Submarines do not fight alone. Effective sea denial requires integration with other systems: coastal defense missiles, mines, surface ships, maritime patrol aircraft, and intelligence networks. A submarine that knows where enemy ships are can position itself for ambush. A submarine operating blind must guess.

Taiwan has invested in complementary capabilities. The Hsiung Feng III anti-ship missile can strike targets at ranges exceeding 150 kilometers. Naval mines—cheap, persistent, and psychologically potent—could channel invasion routes into predictable paths. But the command-and-control architecture that would link these systems remains underdeveloped.

The Ministry of National Defense has acknowledged the problem. Taiwan’s 2025 National Defense Report emphasizes “nine precision weapon systems prioritized for mass production” as part of an asymmetric warfare strategy. The language is encouraging. The implementation is slower.

Coordination with American forces presents additional complications. In a Taiwan contingency, US submarines would almost certainly operate in the same waters as Taiwanese boats. Deconfliction—ensuring allied submarines do not torpedo each other—requires shared communication protocols, agreed patrol areas, and real-time coordination. These arrangements exist in NATO, where decades of exercises have built interoperability. The US-Taiwan relationship, constrained by diplomatic ambiguity, lacks comparable depth.

Wellington Koo, Taiwan’s Minister of National Defense and the first civilian to hold the post in over a decade, has pushed for deeper integration. His background as a lawyer, not a military officer, gives him distance from service parochialism. But institutional resistance runs deep. The navy’s surface warfare community does not naturally cede resources or prestige to submariners. Bureaucratic battles over budget share consume energy that might otherwise go to operational planning.

The Xi Factor

Chinese decision-making adds another variable. Xi Jinping has staked his legacy on “national rejuvenation,” a project that explicitly includes bringing Taiwan under Beijing’s control. The timeline is unclear—analysts debate whether Xi faces a hard deadline or merely a preference for resolution during his tenure—but the direction is not.

Xi’s psychology matters. His formative experience during the Cultural Revolution, when his family was persecuted and his father imprisoned, left deep marks. He trusts no one fully. He centralizes power obsessively. He eliminates potential rivals preemptively. These traits shape how he processes information about Taiwan.

A leader who fears betrayal may discount intelligence that suggests caution. A leader who demands loyalty may receive assessments that tell him what he wants to hear. If Xi believes Taiwan’s submarines pose minimal threat—because his admirals assure him Chinese ASW can handle them—he may authorize an invasion that a more skeptical leader would delay.

Conversely, uncertainty about submarine capabilities might reinforce caution. Xi did not rise by taking unnecessary risks. If Taiwan’s submarines create genuine doubt about invasion success, that doubt could extend the timeline for military action, buying time for diplomatic solutions or shifts in the broader strategic environment.

The interaction between Taiwan’s submarine program and Xi’s decision calculus is impossible to model precisely. But the relationship exists. Every additional submarine Taiwan deploys is a variable Xi must consider. Every improvement in crew proficiency is a factor his planners must weigh. The boats matter not only for what they can do but for what Beijing believes they might do.

The Honest Assessment

Taiwan’s indigenous submarine program will not create overwhelming sea denial capability. Eight boats cannot blockade the Taiwan Strait or prevent a determined Chinese invasion. The numbers are too small, the timeline too extended, the adversary too capable.

But “genuine” sea denial does not require overwhelming capability. It requires sufficient capability to impose unacceptable costs and create operational uncertainty. By this standard, Taiwan’s submarines could matter—if the program stays on schedule, if crews achieve proficiency, if integration with other systems improves, and if China’s ASW capabilities do not advance faster than expected.

That is a lot of “ifs.” The honest assessment is that Taiwan is attempting something extraordinarily difficult: building a credible undersea deterrent from scratch, against a rising power with vastly greater resources, on a timeline that may already be too compressed. The effort is not futile. Neither is success assured.

The submarines represent a bet—that eight boats, operated skillfully, integrated effectively, and supported by complementary systems, can complicate Chinese planning enough to extend deterrence. Whether the bet pays off depends on execution, timing, and factors beyond Taiwan’s control.

What Taiwan cannot afford is complacency. The window where submarines might matter is real but finite. Every year of delay, every budget cut, every failure to develop submarine culture narrows that window. The Hai Kun is a beginning, not an achievement. The seven boats that follow will determine whether Taiwan’s undersea gamble succeeds.

FAQ: Key Questions Answered

Q: How many submarines does Taiwan currently have? A: Taiwan operates four submarines: two World War II-era boats used only for training, and two Dutch-built Hai Lung-class boats from the 1980s that constitute the entire combat-capable force. The indigenous program aims to add eight new boats by 2038.

Q: Can Taiwan’s submarines actually sink Chinese invasion ships? A: Yes, but the greater value lies in forcing China to conduct time-consuming anti-submarine warfare operations before any crossing. Even submarines that never fire torpedoes impose delays and resource costs on an invasion fleet.

Q: Why can’t Taiwan just buy submarines from other countries? A: Chinese diplomatic pressure has blocked every foreign submarine sale to Taiwan since the 1980s. The United States has approved technology transfers but does not build diesel-electric submarines itself. Taiwan’s indigenous program emerged from necessity, not preference.

Q: How good is China’s anti-submarine warfare capability? A: Improving but uneven. China has invested heavily in ASW aircraft, surface ship sensors, and undersea surveillance networks. However, US assessments indicate Chinese sonar technology remains one to two generations behind Western systems, and deep-water ASW capability remains limited.

The Narrowing Window

The Hai Kun sits in Kaohsiung harbor, a steel promise of capabilities yet to come. Its sisters remain unbuilt, their keels not yet laid, their crews not yet trained. Across the Strait, Chinese shipyards work three shifts. ASW aircraft accumulate flight hours. The undersea surveillance network grows.

Taiwan’s submarine program is neither too little nor too late—not yet. But the margin for error has vanished. The boats must come on schedule. The crews must achieve proficiency. The systems must integrate. And Beijing must believe, despite every intelligence assessment to the contrary, that those eight submarines might be enough to turn an invasion into a catastrophe.

That belief is the real weapon. The submarines are merely its delivery system.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- US Department of Defense Annual Report on China 2024 - Primary source for assessments of Chinese ASW capabilities and limitations

- China Maritime Report No. 38: PLAN Anti-Submarine Warfare Aircraft - Detailed analysis of Chinese ASW doctrine and platforms

- Taiwan’s 2025 National Defense Report via Naval News - Taiwan’s official assessment of asymmetric warfare investments

- CSBC Corporation Background - History and capabilities of Taiwan’s submarine builder

- NAVSEA Technology Development Roadmap - US naval technology development context

- The Decibel Countdown: China’s Submarine Weakness - Analysis of temporal dynamics in undersea competition

- Taiwan’s Navy and Sea Denial - Strategic assessment of Taiwan’s naval capabilities