Taiwan's porcupine strategy has sharper quills but an uncertain heart

The island's shift toward asymmetric warfare addresses genuine tactical gaps in its defense posture. But missiles and drones cannot solve the deeper problem: whether Taiwanese society can sustain the casualties that successful resistance would require.

🎧 Listen to this article

The Porcupine’s Dilemma

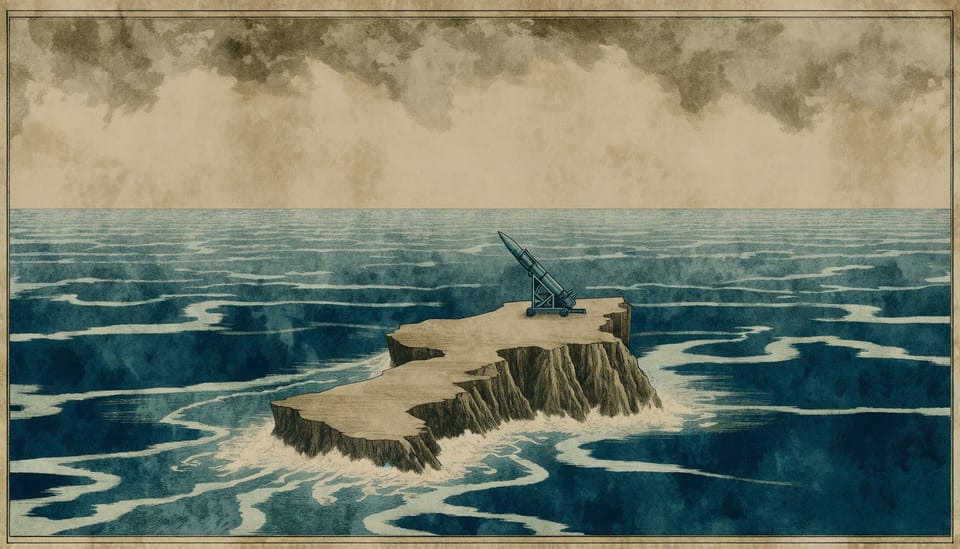

Taiwan’s military planners have embraced a seductive idea: that the island can deter a Chinese invasion by becoming too painful to swallow. The “porcupine strategy,” as it has come to be known, would replace expensive fighter jets and destroyers with swarms of missiles, drones, and sea mines—weapons that are cheap, dispersible, and deadly. The logic is elegant. China’s People’s Liberation Army may outnumber Taiwan’s forces ten to one, but an amphibious assault across 130 kilometers of open water remains the most complex military operation imaginable. Fill those waters with mobile anti-ship missiles and smart mines, and even a superpower might hesitate.

Yet elegant logic can obscure uncomfortable questions. Taiwan’s asymmetric warfare pivot assumes that the island’s real problem is tactical: that it has been buying the wrong weapons for the wrong war. But what if the deeper vulnerability lies elsewhere—in the willingness of Taiwan’s citizens and leaders to endure the casualties that any serious defense would require? The porcupine can bristle all it wants. If it lacks the nerve to hold its quills steady, the predator will simply wait.

The Doctrine That Wasn’t

Admiral Lee Hsi-min understood the problem better than most. As Taiwan’s Chief of General Staff from 2017 to 2019, he championed what became known as the Overall Defense Concept (ODC)—a systematic shift away from the traditional war of attrition toward asymmetric thinking. His vision was blunt: abandon prestige platforms, embrace “small things in large numbers,” and accept that Taiwan could never match China plane for plane or ship for ship. Victory, in Lee’s conception, meant making invasion so costly that Beijing would never attempt it.

The ODC represented genuine strategic innovation. Lee proposed building 60 micro missile boats—small, fast, and expendable—to swarm Chinese landing craft. He pushed for mobile coastal defense systems that could survive initial strikes and continue firing from concealed positions. He emphasized sea mines, which remain devastatingly effective against amphibious operations and cost a fraction of what destroyers cost to build.

Then Lee retired. His successors quietly shelved the missile boats. The military establishment, wedded to conventional platforms that confer prestige and support established career paths, reasserted itself. Taiwan’s 2023 National Defense Report still invokes asymmetric concepts, but according to defense analysts, the ODC “is not explicitly used” in current strategy—its “main ideas are included” but diluted by institutional inertia.

This pattern reveals something important. Taiwan’s military can articulate asymmetric doctrine. It struggles to implement it. The gap between strategic pronouncement and procurement reality suggests that doctrinal shifts alone cannot overcome the bureaucratic and political forces that favor traditional force structures. The porcupine’s quills exist mostly on paper.

What the Polls Actually Show

Surveys of Taiwanese public opinion offer what appears to be reassuring news. The Institute for National Defense and Security Research has consistently found that between two-thirds and three-quarters of citizens express willingness to fight if China invades. A 2024 survey found 68% either “very willing” (42%) or “somewhat willing” (26%) to defend Taiwan in case of attack. These numbers have held steady even as cross-strait tensions have intensified.

But willingness to fight in a hypothetical survey is not the same as tolerance for actual casualties. Research into Taiwanese attitudes toward battle deaths reveals a more complicated picture. Citizens respond very differently to military versus civilian casualties. They are “more likely to view affected civilians as people who could be their family members” than they are to view soldiers the same way. This asymmetry matters enormously for a conflict that would inevitably blur the line between combatant and civilian.

Taiwan’s demographic reality amplifies the problem. The island’s fertility rate has collapsed to among the lowest in the world. Each child has become precious in ways that larger societies cannot fully comprehend. Parents who might have accepted the loss of one son among four now face the prospect of losing their only child. The mathematics of grief have shifted. Per-child loss aversion has intensified precisely as the strategic situation has worsened.

Generational divides compound the challenge. Older Taiwanese, many of whom remember authoritarian rule and the genuine possibility of invasion in earlier decades, express higher willingness to fight. Younger citizens, raised in democracy and prosperity, show more ambivalence. They have more to lose and less memory of what life without self-determination looked like. A conflict that stretched beyond days into weeks would test these generational fault lines severely.

The Political Will Problem

If public opinion presents complexities, elite political will presents contradictions. Taiwan’s defense budget has increased under successive Democratic Progressive Party governments, and the extension of conscription from four months to one year represents a genuine policy shift. President Lai Ching-te has appointed Wellington Koo, a human rights lawyer with no military background, as defense minister—a signal that civilian control and institutional reform matter more than military tradition.

Yet Taiwan’s political system contains structural features that work against sustained defense investment. The Legislative Yuan operates on electoral cycles that reward short-term spending over long-term capability building. Opposition parties have repeatedly blocked special defense budgets, treating national security as a partisan football rather than a shared imperative. According to analysis of Taiwan’s defense governance, the interplay between party competition and defense policy creates systematic underinvestment in capabilities that take years to develop.

The KMT, Taiwan’s main opposition party, has historically favored engagement with Beijing and skepticism toward American security commitments. This is not treason—it reflects a genuine strategic calculation that accommodation offers better odds than confrontation. But it means that Taiwan’s defense posture swings with electoral outcomes in ways that China can observe and exploit. Beijing need not invade if it can simply wait for a more amenable government.

More troubling still is the evidence of Chinese influence operations targeting Taiwan’s political will directly. The PLA’s “three warfares” doctrine—legal warfare, media warfare, and psychological warfare—treats Taiwanese resolve as a center of gravity to be attacked. Research into cognitive warfare effects suggests that sustained disinformation campaigns are “causing mental disarray and confusion among the Taiwanese population,” eroding confidence in both the government and the possibility of successful resistance.

The Training Gap

Even if Taiwan’s leaders and citizens possessed iron will, the question remains whether its military could translate that will into effective resistance. Here the evidence is troubling. Taiwan’s reserve forces—the backbone of any prolonged defense—suffer from inadequate training, outdated equipment, and unclear mobilization procedures.

The annual Han Kuang exercises showcase Taiwan’s defensive capabilities for domestic and international audiences. But exercises that emphasize scripted scenarios and predictable outcomes do not prepare forces for the chaos of actual combat. Analysis of Taiwan’s military preparedness suggests that Han Kuang has become “performative,” satisfying political requirements for demonstrating asymmetric warfare without forcing the uncomfortable institutional restructuring that genuine capability would require.

The gap between exercise performance and combat readiness is not unique to Taiwan. But Taiwan faces an adversary that has studied its weaknesses for decades and would attack precisely where those weaknesses are greatest. A military trained through rote learning and scripted exercises will struggle to adapt when plans fail—and plans always fail on contact with the enemy.

Sleep deprivation, stress, and the psychological burden of watching comrades die degrade cognitive function rapidly. Studies of combat effectiveness show that higher mental processes collapse first under pressure. Soldiers who have never experienced genuine uncertainty in training will face it for the first time when the stakes are existential. The asymmetric weapons Taiwan has purchased assume operators who can function under these conditions. Nothing in Taiwan’s training regime prepares them for it.

The Temporal Mismatch

Taiwan’s strategic situation involves a fundamental mismatch in time horizons. China operates on generational timescales. Xi Jinping has declared that Taiwan’s unification cannot be passed to future generations indefinitely, but “indefinitely” in Chinese strategic culture means decades, not years. The PLA can afford to wait, to probe, to prepare—and to strike when conditions favor success.

Taiwan’s democracy operates on electoral cycles. Every four years, the island’s strategic direction is up for renegotiation. Defense investments that take a decade to mature must survive multiple changes in government. Weapons systems ordered today may be canceled by administrations elected tomorrow. This temporal asymmetry gives Beijing enormous advantages that no amount of missiles can offset.

The United States adds another temporal layer. American security guarantees to Taiwan remain deliberately ambiguous—a policy of “strategic ambiguity” designed to deter both Chinese aggression and Taiwanese provocation. But American attention spans are short, and American domestic politics increasingly volatile. Survey data on Taiwanese perceptions shows that willingness to fight correlates strongly with perceived American support. If that perception wavers, so might Taiwanese resolve.

Ukraine offers a cautionary parallel. Western support for Kyiv has proven more durable than many expected, but it has also proven more contested and more conditional. Taiwan cannot assume it would receive similar treatment. An island 130 kilometers from the Chinese coast presents logistical challenges that Ukraine’s land borders do not. If the first weeks of conflict went badly, American domestic politics might counsel cutting losses rather than doubling down.

What Asymmetric Warfare Actually Requires

The fundamental insight of asymmetric warfare is that weaker powers can impose costs on stronger powers by refusing to fight on the stronger power’s terms. Guerrilla movements throughout history have demonstrated that conventional military superiority does not guarantee victory against determined resistance. But guerrilla warfare requires something that Taiwan’s asymmetric doctrine has not adequately addressed: the willingness to accept enormous casualties over extended periods.

The Viet Cong lost every major engagement with American forces. They won the war because they were willing to absorb losses that American society would not tolerate. Afghan resistance to Soviet occupation succeeded not through tactical brilliance but through stubborn refusal to surrender despite devastating casualties. These examples are not encouraging templates for Taiwan—they represent the bloodiest possible path to survival.

Taiwan’s asymmetric pivot assumes that deterrence will work—that the threat of costly resistance will prevent invasion from occurring. This may be correct. But deterrence that fails becomes a war plan, and Taiwan’s war plan requires a society willing to fight building by building, block by block, accepting casualties that would dwarf anything in the island’s modern experience. Nothing in Taiwan’s political culture, training regime, or public discourse has prepared its citizens for that reality.

The porcupine strategy works only if the porcupine is willing to die with its quills extended. Taiwan has purchased the quills. It has not demonstrated the willingness.

The Path Not Taken

Alternative approaches exist. Taiwan could invest more heavily in civil defense, hardening critical infrastructure and training citizens for the chaos of urban warfare. It could reform reserve training to emphasize realistic scenarios rather than scripted exercises. It could build genuine whole-of-society resilience through programs that connect military preparation to civilian life.

Some of this is happening. The extension of conscription represents a step toward more serious military preparation. Civil defense drills have increased in frequency and realism. But these efforts remain marginal compared to the scale of the challenge. Taiwan spends roughly 2.5% of GDP on defense—significant, but not the level that existential threat would seem to warrant.

The deeper problem is that genuine preparation for high-casualty conflict requires political leadership willing to tell citizens uncomfortable truths. It requires acknowledging that deterrence might fail, that American help might not arrive in time, and that successful resistance would cost tens of thousands of lives. No democratic politician wants to deliver that message. The incentives all point toward optimism, toward reassurance, toward the comfortable fiction that better weapons will solve the problem.

Taiwan’s asymmetric warfare pivot addresses real tactical gaps. Mobile missiles are better than stationary ones. Drones are better than nothing. Sea mines genuinely complicate amphibious operations. But these improvements operate at the margin of a problem whose core is political and psychological, not technical.

What Happens Next

The most likely trajectory is continuation of current trends. Taiwan will purchase more asymmetric weapons while maintaining significant investment in traditional platforms. Training will improve incrementally without fundamental reform. Public willingness to fight will remain high in surveys and untested in practice. Political will among elites will fluctuate with electoral cycles and partisan competition.

This trajectory is not catastrophic. It may be sufficient to maintain deterrence if China concludes that the costs of invasion outweigh the benefits. But it leaves Taiwan vulnerable to scenarios where deterrence fails—where Beijing decides that the window for action is closing, or where a crisis escalates beyond anyone’s control.

The uncomfortable truth is that Taiwan’s real vulnerability—political will to sustain casualties—cannot be addressed through procurement decisions. It requires a transformation in how Taiwanese society thinks about risk, sacrifice, and national identity. That transformation would take a generation to accomplish, and Taiwan may not have a generation.

The porcupine has grown sharper quills. Whether it has grown a stronger heart remains the question that matters most.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: How long could Taiwan realistically hold out against a Chinese invasion? A: Military analysts generally estimate that Taiwan could resist an initial assault for weeks to months, depending on how effectively it employs asymmetric defenses and whether the United States intervenes. The critical variable is not military capability but societal willingness to sustain resistance as casualties mount.

Q: Does Taiwan have enough missiles and drones to implement its asymmetric strategy? A: Taiwan has significantly increased procurement of anti-ship missiles, mobile launchers, and unmanned systems, but stockpiles remain below what many defense analysts consider adequate. Domestic production capacity is expanding but cannot yet match the scale of potential Chinese attacks.

Q: Would the United States definitely defend Taiwan if China invaded? A: American policy maintains deliberate ambiguity on this question. While recent administrations have made increasingly explicit statements suggesting intervention, no formal defense treaty exists. Taiwan’s defense planning must account for scenarios where American help arrives late, arrives limited, or does not arrive at all.

Q: How do younger Taiwanese feel about defending the island compared to older generations? A: Surveys consistently show lower willingness to fight among younger Taiwanese compared to those over 50. This generational gap reflects different historical experiences: older citizens remember authoritarian rule and earlier invasion threats, while younger citizens have known only democracy and prosperity.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- Taiwan’s National Defense Report 2023 - Official Ministry of National Defense assessment of threats and strategy

- Institute for National Defense and Security Research surveys - Ongoing polling on defense attitudes and policy implementation

- Admiral Lee Hsi-min’s Hoover Institution remarks - The ODC architect’s assessment of Taiwan’s strategic challenges

- Academic research on Taiwanese casualty tolerance - Scholarly analysis of public attitudes toward battle deaths

- Global Taiwan Institute analysis - Expert assessment of asymmetric doctrine implementation

- Taiwan-US public opinion surveys - Cross-national polling on defense attitudes and alliance perceptions

- Taiwan politics research - Academic review of political will literature