Taiwan's outlying islands and the HIMARS gamble: hours, not days

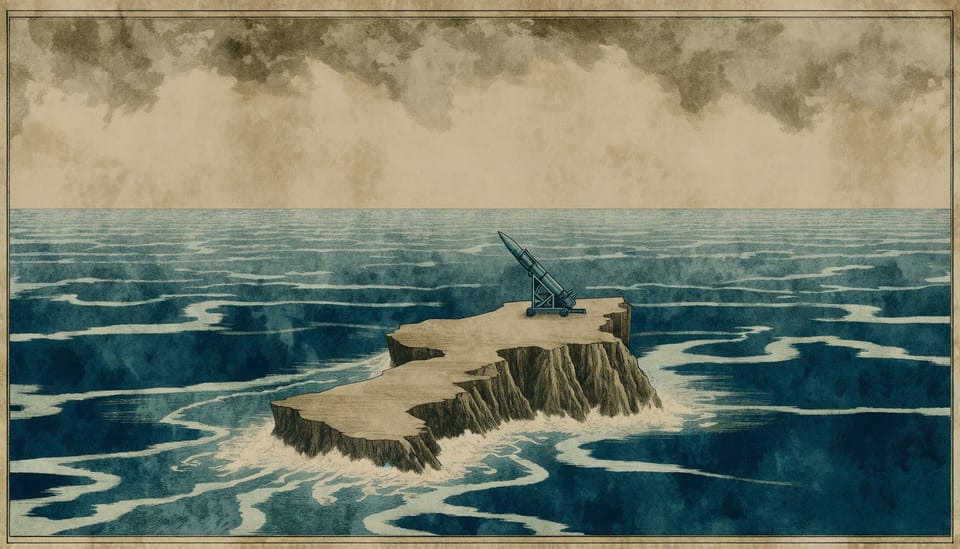

Taiwan plans to deploy HIMARS launchers to islands within sight of the Chinese coast. The launchers could devastate an invasion fleet—if they survive long enough to fire. Military logic and political reality collide in a space measured in minutes.

🎧 Listen to this article

The Twelve-Mile Bet

Taiwan’s military planners face a problem that resembles a chess puzzle with a ticking clock. Deploy HIMARS launchers to the outlying islands—Kinmen, Matsu, Penghu, Dongyin—and you gain the ability to strike Chinese invasion fleets and staging areas in Fujian within seven minutes of launch. Keep them on the main island, and they survive longer but arrive too late to matter. The question is not whether forward-deployed HIMARS would be effective. It is whether the islands can remain functional long enough for the launchers to fire.

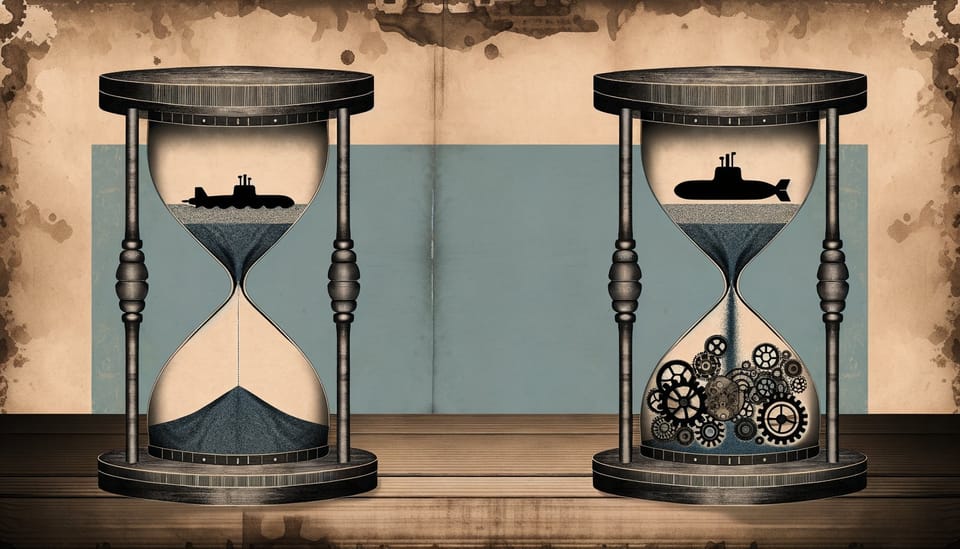

The answer depends on hours, not days. And the hours favor China.

Geography as Destiny

Kinmen sits six miles from Xiamen. On a clear day, residents can see the Chinese coastline without binoculars. Matsu perches similarly close to Fuzhou. Penghu, farther out in the Taiwan Strait, offers more breathing room but less cover. Dongyin, the northernmost garrison, watches the approaches like a lighthouse that shoots back.

These islands are not defensible in any conventional sense. They are defensible briefly. The distinction matters.

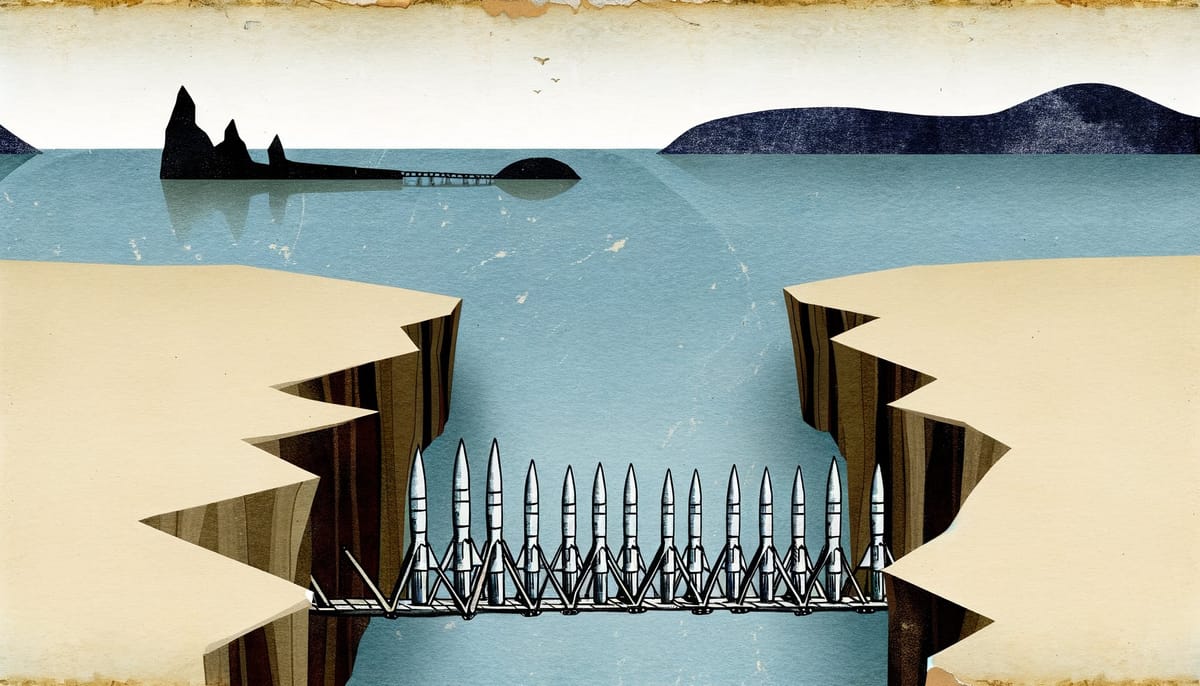

Taiwan’s 2025 National Defense Report emphasizes “Resolute Defense and Multi-Domain Deterrence”—bureaucratic language for a simple idea: make the opening hours of any invasion so costly that Beijing hesitates. HIMARS fits this doctrine precisely. Armed with ATACMS missiles, a single launcher can reach targets 300 kilometers away. According to Focus Taiwan, that gives Taiwan its most time-efficient counterstrike option, matching the flight time of Chinese rockets heading the other direction.

The operational logic is seductive. Forward-deploy HIMARS to the islands. When invasion preparations become unmistakable—amphibious ships massing, troops loading, aircraft surging—launch everything. Hit the ports. Hit the staging areas. Hit the ships before they sail. Buy time for the main island’s defenses to activate.

But the logic contains a trap. HIMARS must survive long enough to fire. And the People’s Liberation Army has spent two decades ensuring that nothing on those islands survives the opening salvo.

The Suppression Calculus

The PLA Rocket Force maintains an inventory purpose-built for this problem. The DF-11, DF-15, and DF-16 short-range ballistic missiles can saturate small island targets with precision that Cold War planners would have found fantastical. According to NDU Press analysis, China’s missile forces have evolved from area-denial weapons to precision strike instruments capable of targeting individual hardened facilities.

The cost-exchange ratio favors the attacker overwhelmingly. A DF-15 costs roughly $1.5 million. A HIMARS launcher costs $5.1 million, and the ATACMS missiles it fires cost over $1 million each. China can afford to expend ten missiles to destroy one launcher. Taiwan cannot afford the reverse.

This creates what defense economists call an “attrition trap”—though that phrase understates the violence of the arithmetic. Taiwan’s HIMARS inventory is measured in dozens. China’s relevant missile inventory is measured in hundreds. Even if every HIMARS launcher on the outlying islands fires its full load before destruction, the aggregate effect on Chinese invasion capacity remains modest. The PLA can absorb the losses. Taiwan cannot replace the launchers.

The survivability window shrinks further when you account for PLA intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities. Satellites, drones, coastal radars, and signals intelligence create what military planners call “persistent ISR coverage.” A HIMARS launcher that moves emits signatures. A HIMARS launcher that fires emits more. The shoot-and-scoot tactics that proved effective in Ukraine against Russian forces face a different adversary here—one with shorter engagement distances, denser sensor coverage, and no supply line vulnerabilities to exploit.

The Tunnel Paradox

One factor complicates the pessimistic calculus: Kinmen and Matsu are honeycombed with tunnels.

During the Cold War, Taiwan fortified these islands against the invasion that never came. The tunnel networks were built to shelter troops and supplies from artillery bombardment. They were not surveyed with GPS. They were not mapped with modern precision. And they remain, decades later, largely intact.

Research on Kinmen’s geostrategic significance notes that these irregular, difficult-to-map networks may survive precision strikes better than modern GPS-surveyed facilities. The irony is structural: obsolescence becomes an asset. Chinese targeting algorithms optimize for known coordinates. Unknown coordinates cannot be targeted.

A HIMARS launcher that disappears into an unmapped tunnel after firing presents a genuine problem for PLA kill chains. The launcher must emerge to fire again, but the emergence point becomes unpredictable. Multiply this across multiple launchers and multiple tunnels, and the suppression problem grows more complex.

But complexity is not immunity. The tunnels buy time. They do not buy victory. A launcher that fires once and hides can fire again—if it has missiles to fire, crews to operate it, and communications to receive targeting data. Each of these dependencies creates vulnerabilities that the PLA can exploit.

The Logistics of Isolation

HIMARS launchers consume ammunition at rates that strain peacetime logistics. In combat, the strain becomes existential.

Each launcher carries six GMLRS rockets or one ATACMS missile. Reloading requires a specialized vehicle, trained crews, and—critically—missiles to load. The outlying islands have limited storage capacity. Resupply under blockade conditions ranges from difficult to impossible.

Taiwan’s military reportedly plans to pre-position ammunition stocks on the islands. According to Taiwan News, the deployment to Penghu and Dongyin would include forward-positioned munitions. But pre-positioning creates its own vulnerabilities. Ammunition depots become priority targets. Hardened storage facilities resist destruction but not indefinitely. And once the stocks are exhausted, the launchers become expensive decoys.

The resupply problem compounds under realistic invasion scenarios. Chinese naval and air superiority in the immediate vicinity of the outlying islands would be established within hours of hostilities beginning. Surface vessels attempting resupply would face anti-ship missiles, submarines, and aircraft. Airlift would require air superiority that Taiwan cannot guarantee. The islands would be, in military terminology, “isolated”—cut off from the main island’s resources and forced to fight with what they have.

This isolation transforms the operational question. Forward-deployed HIMARS are not a sustained capability. They are a one-time expenditure. The question becomes: what can Taiwan accomplish with that single expenditure?

The Seven-Minute Window

The answer lies in timing.

An ATACMS missile launched from Penghu reaches targets in Fujian in approximately seven minutes—roughly the same time Chinese missiles need to reach Taiwan proper. This creates a narrow window of mutual vulnerability. If Taiwan’s forward-deployed HIMARS can launch before Chinese suppression fires destroy them, the missiles will arrive before the invasion fleet sails.

The targets matter. Ports, staging areas, fuel depots, command nodes, air defense radars—these are the critical vulnerabilities of an amphibious operation. An invasion force loading troops and equipment presents concentrated targets that precision munitions can devastate. The same force dispersed at sea becomes harder to engage. The same force landed on Taiwan’s beaches becomes a ground war.

Taiwan’s optimal strategy, then, is not to preserve its forward-deployed HIMARS for sustained operations. It is to fire them immediately upon confirmed invasion indicators, accept their destruction, and use the damage inflicted to delay Chinese timelines.

This is not a defensive strategy in any traditional sense. It is a spoiling attack. The islands become expendable platforms for a one-time strike that buys hours—perhaps a day—for the main island’s defenses to activate and for international responses to materialize.

The Political Dimension

But islands are not merely military platforms. They are populated territory.

Kinmen has over 140,000 residents. Matsu has approximately 14,000. Penghu exceeds 100,000. These are not garrison populations; they are civilians with homes, businesses, and lives that predate any military consideration.

The Institute for the Study of War analysis notes that China could pursue a “short-of-war coercion campaign” against Kinmen specifically, exploiting its proximity and the political costs of defending it. The islands exist in a legal gray zone: the Taiwan Relations Act, which governs U.S. security commitments to Taiwan, defines “Taiwan” in ways that may exclude Kinmen and Matsu. This ambiguity is not accidental. It provides Washington flexibility—and Taipei uncertainty.

Forward-deploying HIMARS to these islands raises the stakes for everyone. Taiwan signals resolve but also accepts that the islands may be sacrificed. China must decide whether to suppress the launchers preemptively—an act of war—or accept the damage they will inflict. The United States must determine whether attacks on the outlying islands trigger its security commitments or fall outside them.

The political calculus interacts with the military calculus in ways that neither side fully controls. A Chinese decision to suppress HIMARS on Kinmen before any invasion of Taiwan proper might be intended as limited coercion. Taiwan might interpret it as the opening of general war. The escalation dynamics are unstable precisely because the islands occupy ambiguous territory—militarily valuable, legally contested, politically symbolic.

The Deception Option

One alternative to accepting destruction is avoiding detection.

Military deception has a long history, and HIMARS launchers are not uniquely difficult to disguise. Decoy launchers, thermal signature management, and dispersal across multiple concealed positions can complicate Chinese targeting. The tunnels provide natural concealment. The islands’ terrain—particularly Kinmen’s granite ridges—offers additional cover.

Research on military mimicry concepts suggests that deception works best when the cost of verification exceeds the cost of the decoy. If China must expend multiple precision missiles to destroy each potential HIMARS position, and most positions are empty, the cost-exchange ratio shifts. Taiwan cannot win the attrition war, but it can make the war more expensive.

The limitation is sensor density. Chinese ISR capabilities over the Taiwan Strait are not comparable to Russian capabilities in Ukraine. The distances are shorter. The coverage is denser. The integration is tighter. Deception that works for hours may not work for days. And the suppression campaign would not be a single strike but a sustained effort to eliminate all potential launcher positions.

Deception buys time. Everything buys time. The question is whether the time purchased exceeds the time required.

What Actually Happens

The most likely scenario unfolds in phases.

Phase one: Taiwan detects unmistakable invasion preparations—troop movements, naval surges, aircraft positioning. Political leaders face the decision to launch preemptively or wait for the first Chinese strike. Waiting preserves international legitimacy but sacrifices military advantage. Launching first maximizes HIMARS effectiveness but risks being blamed for starting the war.

Phase two: Chinese suppression fires target the outlying islands. The first salvos prioritize known military positions—air defense sites, command facilities, ammunition depots, and suspected HIMARS locations. Some launchers survive in tunnels or through deception. Others are destroyed before firing.

Phase three: Surviving HIMARS launch against pre-planned targets in Fujian. The missiles arrive within minutes. Damage to ports and staging areas delays the invasion timeline by hours to perhaps a day. Chinese second-wave suppression fires destroy remaining launchers and supporting infrastructure.

Phase four: The outlying islands are isolated and effectively neutralized. The invasion proceeds against the main island, delayed but not prevented. The forward-deployed HIMARS have accomplished their mission—buying time—but the time purchased is measured in hours, not weeks.

This is not a satisfying conclusion. It offers no decisive victory, no elegant solution, no comfortable assurance that the islands can “survive long enough.” The honest answer is that they probably cannot survive long enough to make forward-deployed HIMARS a sustained capability. They can survive long enough to make them a one-time spoiling attack.

Whether that is enough depends on what Taiwan does with the hours purchased. And that question extends far beyond the outlying islands.

FAQ: Key Questions Answered

Q: How many HIMARS launchers does Taiwan have? A: Taiwan has received or ordered approximately 29 HIMARS launchers from the United States, though deliveries have been delayed by supply chain constraints and competing demands from Ukraine. The exact number currently operational and their deployment locations remain classified.

Q: Could the United States defend Taiwan’s outlying islands directly? A: The Taiwan Relations Act commits the U.S. to provide Taiwan with defensive weapons but does not guarantee direct military intervention. The Act’s definition of “Taiwan” may exclude Kinmen and Matsu, creating legal ambiguity about whether attacks on these islands would trigger U.S. security commitments.

Q: Why not keep all HIMARS on the main island where they’re safer? A: Launchers on the main island would survive longer but arrive too late to disrupt invasion preparations. The seven-minute flight time from forward islands allows strikes against Chinese forces before they embark; strikes from the main island would hit dispersed forces at sea or already landed.

Q: What happens to civilians on the outlying islands during an attack? A: Taiwan has evacuation plans, but the islands’ proximity to China—Kinmen is six miles from the mainland—makes evacuation under combat conditions extremely difficult. Most civilian casualties in a Taiwan Strait conflict would likely occur on these forward islands in the opening hours.

The Uncomfortable Truth

Taiwan’s outlying islands cannot survive a determined Chinese assault. They were never designed to. Their value lies not in what they can hold but in what they can cost.

Forward-deployed HIMARS transform these islands from symbolic territory into kinetic platforms. The transformation is irreversible once the launchers arrive. China must then decide whether to tolerate the threat or eliminate it—and elimination means war.

This is deterrence through entanglement, not through defense. The islands become tripwires rather than fortresses. Their survival is measured not in days of resistance but in salvos delivered before destruction.

Whether this constitutes “operational effectiveness” depends on how you define the term. If effectiveness means sustained combat capability, the answer is no. If effectiveness means inflicting costs that delay invasion timelines and complicate Chinese planning, the answer is yes—briefly.

The twelve miles between Kinmen and Xiamen compress all the ambiguities of great-power competition into a space small enough to see with the naked eye. Taiwan bets that the hours its forward forces can buy will be enough. China bets that they will not. Neither side knows who is right.

The islands will answer the question. They will not survive the answering.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- Beyond the Median Line: Reassessing Kinmen’s Geostrategic Significance - Foundation for Strategic Research analysis of Kinmen’s evolving military and political significance

- Exploring a PRC Short-of-War Coercion Campaign to Seize Taiwan’s Kinmen Islands - Institute for the Study of War scenario analysis of Chinese coercion options

- Making Sense of China’s Missile Forces - NDU Press assessment of PLA Rocket Force capabilities and doctrine

- People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force Order of Battle 2023 - James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies inventory analysis

- Taiwan: China’s Gray Zone Doctrine in Action - Small Wars Journal examination of Chinese pressure tactics

- Focus Taiwan: ATACMS Counterstrike Analysis - Reporting on Taiwan’s precision strike timelines and capabilities

- ROC National Defense Report 2025 - Taiwan Ministry of National Defense official strategy document

- Commander’s Toolkit: PLARF - Air University China Aerospace Studies Institute assessment