Taiwan's HIMARS gamble: Why Taipei is deploying missiles it cannot protect

Taiwan plans to station American-supplied precision weapons on islands within easy reach of Chinese missiles. The systems will likely be destroyed within hours of any conflict. That may be exactly the point.

🎧 Listen to this article

The Artillery Altar

Taiwan’s outlying islands have always served a dual purpose: military outposts and political symbols. Now they may become something else entirely—sacrificial offerings on the altar of deterrence theory.

The planned deployment of M142 HIMARS launchers to Penghu and Dongyin islands represents Taiwan’s most significant forward positioning of American-supplied precision strike systems. Proponents argue these weapons will complicate Chinese invasion planning, forcing the People’s Liberation Army to account for threats from multiple directions. Critics see expensive targets waiting to be destroyed in the opening hours of any conflict. Both perspectives miss what matters most.

The real question is not whether HIMARS can survive on these islands. They almost certainly cannot—not for long. The question is whether their presence changes Chinese calculations before the first shot is fired, and what happens to escalation dynamics if Beijing decides to test that proposition.

Geography as Constraint

Kinmen sits ten kilometers from the Chinese mainland. Residents can see Xiamen’s skyline on clear days. Matsu lies even closer to Fujian province. Penghu occupies the Taiwan Strait’s midpoint, roughly fifty kilometers west of Taiwan proper. Dongyin, the northernmost garrison, watches the approaches from the East China Sea.

These are not defensible positions in any conventional sense. Kinmen’s 140,000 civilians live under the shadow of thousands of PLA rockets and missiles. Matsu’s 12,000 residents share that exposure. The islands offer no strategic depth, no room for maneuver, no terrain to exploit. What they offer is proximity—to Chinese shipping lanes, to PLA staging areas, to the psychological boundary between peace and war.

HIMARS changes the military arithmetic on these islands without changing the geography. A single launcher carries one pod with six GMLRS rockets or one ATACMS missile. GMLRS reaches 92 kilometers with precision guidance. ATACMS exceeds 165 kilometers. From Penghu, this puts Chinese naval vessels in the Strait at risk. From Dongyin, it threatens amphibious staging areas along the Fujian coast.

The December 2024 arms package—$4.05 billion for 82 HIMARS launchers, 420 ATACMS missiles, and 756 GMLRS rocket pods—represents the largest single American weapons sale to Taiwan. The systems will take years to deliver and integrate. But the political signal arrives immediately.

The Survivability Problem

Taiwan’s defense ministry understands the vulnerability calculus. The 2025 National Defense Report emphasizes “precision, mobility, lethality, dispersion, survivability and cost effectiveness” as requirements for weapons systems. HIMARS satisfies most of these criteria on Taiwan’s main island, where road networks allow shoot-and-scoot tactics and terrain provides concealment. On the outlying islands, the equation inverts.

Kinmen’s road network is constrained. Matsu’s is worse. Penghu offers slightly more room to maneuver, but satellite reconnaissance and drone surveillance compress the hide-and-seek window to hours rather than days. The PLA’s counter-ISR capabilities have matured dramatically. Synthetic signatures from drone swarms can confuse defenders, but they cannot hide a HIMARS launcher from persistent overhead surveillance.

Russian electronic warfare systems have demonstrated the ability to jam GPS guidance on GMLRS rockets in Ukraine. The PLA’s electronic warfare capabilities exceed Russia’s in sophistication and density. Terrain-referenced navigation provides backup, but degraded accuracy undermines the precision that makes HIMARS valuable. A system that cannot hit its targets becomes an expensive liability.

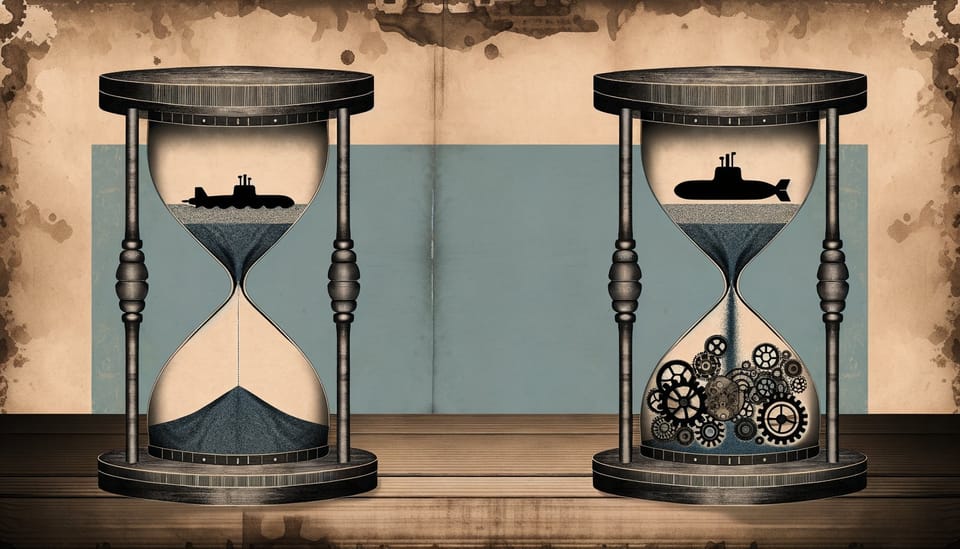

The operational lifespan of forward-deployed HIMARS in a shooting war compresses toward hours, not days. This is not speculation—it is the consensus assessment of analysts who have studied PLA strike capabilities against fixed and semi-mobile targets. Taiwan’s military planners know this. They are deploying anyway.

The Logic of Vulnerability

Why place expensive weapons systems where they cannot survive? The answer lies in what military theorists call “tripwire” deployments—forces positioned not to win battles but to guarantee involvement.

American troops in South Korea during the Cold War served this function. Too few to repel a North Korean invasion, they ensured that any attack would kill Americans and trigger a full U.S. response. The vulnerability was the point. Dead Americans meant American escalation.

Taiwan’s HIMARS deployment follows similar logic, but with crucial differences. American forces are not stationed on the outlying islands. American contractors may be present for maintenance and training, but the Taiwan Relations Act carefully excludes Kinmen and Matsu from its scope while including Penghu. The legal architecture creates ambiguity precisely where clarity would matter most.

The 1979 act requires the United States to “provide Taiwan with arms of a defensive character” and “maintain the capacity” to resist coercion. It does not commit American forces to intervene. This distinction matters enormously. A Chinese strike on Penghu-based HIMARS kills Taiwanese soldiers operating American equipment. It does not automatically trigger the response that dead American soldiers would.

Yet the presence of American-supplied precision weapons creates what scholars call “organic, rhizomatic obligation networks”—informal commitments that accumulate through equipment integration, training relationships, and shared operational planning. These networks contradict formal treaty-based alliances while generating their own binding force. Washington may not be legally obligated to respond to an attack on Penghu. It may find itself politically unable to avoid responding.

Deterrence by Denial or Deterrence by Punishment?

The distinction matters. Deterrence by denial aims to convince an adversary that military objectives cannot be achieved—that invasion will fail. Deterrence by punishment threatens unacceptable costs even if the invasion succeeds. Taiwan’s overall defense concept emphasizes denial: make the island too costly to take and hold.

HIMARS on the outlying islands fits awkwardly into this framework. The systems cannot deny China control of Kinmen or Matsu—they can only impose costs during the seizure. This is punishment, not denial. And punishment-based deterrence requires credible follow-through that Taiwan alone cannot provide.

The asymmetry runs deeper. China operates on what analysts describe as “generational imperial memory cycles.” The Century of Humiliation narrative shapes strategic culture in ways that Western observers consistently underestimate. Taiwan represents unfinished business from the civil war, a wound that festers across decades. Xi Jinping has staked personal legitimacy on reunification, though the timeline remains deliberately ambiguous.

Taiwan’s democratic government resets strategic priorities every four years. Defense budgets face domestic political constraints—the current backlog of approved arms purchases reflects legislative gridlock, not lack of American willingness to sell. Public opinion shifts with each election cycle. The temporal mismatch creates structural vulnerability that no weapons system can address.

The Blockade Scenario

Full-scale amphibious invasion is not China’s only option. Military planners increasingly focus on blockade scenarios—quarantine operations that strangle Taiwan economically without the massive casualties of a beach assault. The outlying islands become crucial in this context.

A blockade of Taiwan proper while leaving Kinmen and Matsu untouched creates legal and political ambiguities that favor Beijing. The islands remain technically accessible. International shipping faces inspection rather than interdiction. China can claim defensive measures rather than acts of war.

HIMARS on Penghu complicates this calculus. Precision strikes against Chinese naval vessels enforcing a blockade transform a gray zone operation into open conflict. The weapons system forces binary choices where Beijing prefers gradual escalation. This may be exactly what Taiwan’s planners intend.

But the forcing function cuts both ways. China might decide that HIMARS deployments require preemptive strikes before the systems become operational. The weapons intended to deter conflict could instead accelerate its arrival. Timing and sequencing matter enormously. Peacetime basing sends different signals than crisis reinforcement. A launcher moved to Penghu during heightened tensions reads as provocation where the same launcher positioned years earlier reads as established fact.

Japan’s Shadow

Taiwan’s outlying islands do not exist in isolation. Japan’s southwestern islands—the Ryukyu chain stretching toward Taiwan—host their own expanding missile capabilities. Tokyo’s reinterpretation of Article 9 constitutional constraints enables collective self-defense arrangements that would have been unthinkable a decade ago. American intermediate-range missiles may soon deploy to Japanese territory.

The result is an emerging “missile archipelago” that creates overlapping threat envelopes across the Taiwan Strait and East China Sea. HIMARS on Taiwan’s islands integrates into this broader architecture, whether or not formal coordination exists. Interoperability between American, Japanese, and Taiwanese systems generates capabilities that exceed the sum of individual deployments.

This integration also generates escalation risks. Japan’s pacifist legal structure means that any decision to engage Chinese forces becomes “a historic, identity-shattering rupture that must be overcompensated for.” The threshold for Japanese involvement is high. Once crossed, the response may be disproportionate to the triggering event. HIMARS on Taiwan’s islands becomes part of a system that nobody fully controls.

The Domestic Politics of Deterrence

Taiwan’s divided government complicates every defense decision. President Lai Ching-te brings hardened views on sovereignty—his formative experience includes witnessing China’s 1996 missile launches during Taiwan’s first free presidential election. Defense Minister Wellington Koo, the first civilian to hold the position since 2000, pushes asymmetric warfare concepts against military establishment resistance.

Public opinion on defense spending remains ambivalent. Tourism revenue from mainland Chinese visitors—once substantial for Kinmen especially—has collapsed amid rising tensions. Local economies suffer. The abstract benefits of deterrence compete with concrete losses in livelihoods. Kinmen residents did not ask to become tripwires.

The $11.1 billion December arms package requires years of delivery and integration. Taiwan’s defense budget cannot absorb unlimited American weapons sales. Choices must be made between HIMARS launchers for outlying islands and other capabilities—submarines, mines, drones—that might better serve the “porcupine strategy” of making Taiwan itself indigestible.

What Changes, What Doesn’t

HIMARS on Taiwan’s outlying islands changes Chinese operational planning. The PLA must now account for precision strikes against amphibious forces, naval vessels, and logistics nodes within range of forward-deployed launchers. This complication has value even if the systems cannot survive sustained combat.

The deployment does not change the fundamental military balance. China’s advantages in mass, proximity, and escalation dominance remain intact. The PLA can destroy HIMARS launchers. The question is whether doing so triggers consequences Beijing wishes to avoid.

The deployment does not resolve American strategic ambiguity. The Taiwan Relations Act’s careful exclusions and inclusions persist. Washington retains the option to respond—or not respond—to attacks on different islands based on circumstances that cannot be predicted in advance.

The deployment does not address Taiwan’s temporal vulnerability. Democratic politics, budget constraints, and public opinion continue to operate on cycles that differ fundamentally from Beijing’s planning horizons. Weapons systems cannot substitute for political will sustained across decades.

The Ritualized Logic

There is something almost ceremonial about forward-deploying precision weapons to positions where they cannot survive. The deployment resembles what anthropologists call “ritualized sacrificial spaces”—locations that derive meaning precisely from their vulnerability, not despite it.

The outlying islands have served this function before. The 1958 Taiwan Strait Crisis saw artillery duels that both sides understood as symbolic rather than decisive. Mao Zedong and Chiang Kai-shek tacitly agreed to maintain Kinmen as a “contingent anchor”—contested enough to justify continued conflict, stable enough to prevent actual resolution. The shelling was theater. The casualties were real.

HIMARS deployment updates this ritual for precision-guided munitions. The weapons are too valuable to waste, too vulnerable to survive, too symbolic to omit. Their presence announces that Taiwan takes defense seriously. Their destruction would announce that China takes reunification seriously. The exchange of signals matters more than the exchange of fire.

This logic has limits. Advances in ISR and precision make “symbolic shelling and warning fires catastrophically outdated.” What worked in 1958 may not work when every launcher can be tracked in real time and destroyed within hours. The ritual depends on both sides understanding the rules. It is not clear that either side’s current leadership shares that understanding.

FAQ: Key Questions Answered

Q: Can HIMARS actually threaten Chinese invasion forces from Taiwan’s outlying islands? A: Yes, but briefly. ATACMS missiles can reach 165+ kilometers, putting Chinese naval vessels and staging areas at risk. However, PLA counter-battery capabilities would likely destroy forward-deployed launchers within hours of conflict initiation. The threat is real but temporary.

Q: Does the Taiwan Relations Act commit the U.S. to defend Taiwan’s outlying islands? A: The act explicitly excludes Kinmen and Matsu from its scope while including Penghu. This creates deliberate legal ambiguity—Washington retains discretion over which attacks trigger which responses. The presence of American-supplied weapons does not automatically trigger American military involvement.

Q: Why would Taiwan deploy expensive weapons to positions where they can’t survive? A: Forward deployment serves political and psychological functions beyond military utility. It signals resolve, complicates Chinese planning, and creates informal obligations that may influence American responses. The vulnerability is partially intentional—tripwire forces derive value from the consequences of their destruction.

Q: How does Japan’s military buildup affect Taiwan’s outlying island deployments? A: Japan’s southwestern islands host expanding missile capabilities that create overlapping threat envelopes with Taiwan’s forward positions. This emerging “missile archipelago” generates integrated deterrence effects while also creating escalation risks that no single government fully controls.

The Altar’s Price

Taiwan’s outlying islands will host HIMARS launchers. The deployment will complicate Chinese planning without fundamentally altering the military balance. It will create informal obligations without formal alliance commitments. It will signal resolve while exposing vulnerability.

The weapons themselves matter less than what their presence reveals about the strategic choices facing all parties. Taiwan cannot defend the outlying islands in any meaningful sense. It can only make their seizure costly—and hope that cost deters. China cannot ignore forward-deployed precision weapons. It can only decide whether to destroy them preemptively or accept the constraints they impose. The United States cannot commit to defending positions the Taiwan Relations Act explicitly excludes. It can only watch as American equipment and perhaps American contractors become entangled in conflicts Washington did not choose.

The altar awaits its offerings. Whether the ritual produces deterrence or catastrophe depends on calculations that none of the participants can make with confidence. That uncertainty is not a bug in the system. It is the system.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- Taiwan Relations Act - Primary legal document governing U.S.-Taiwan defense relations

- Taiwan’s 2025 National Defense Report - Official articulation of Taiwan’s defense strategy and requirements

- HIMARS Technical Specifications - Manufacturer specifications for system capabilities

- Asia Society Policy Institute analysis - Assessment of island seizure contingencies

- George Mason University Taiwan Security Monitor - Visualization of planned HIMARS deployment locations

- Army War College deterrence analysis - Framework for understanding deterrence in Taiwan context

- Air University Press on tripwire forces - Analysis of forward-deployed force concepts

- Forum on the Arms Trade - Documentation of U.S. arms sales to Taiwan