Taiwan's gray-zone dilemma: How to fight fishing boats without starting a war

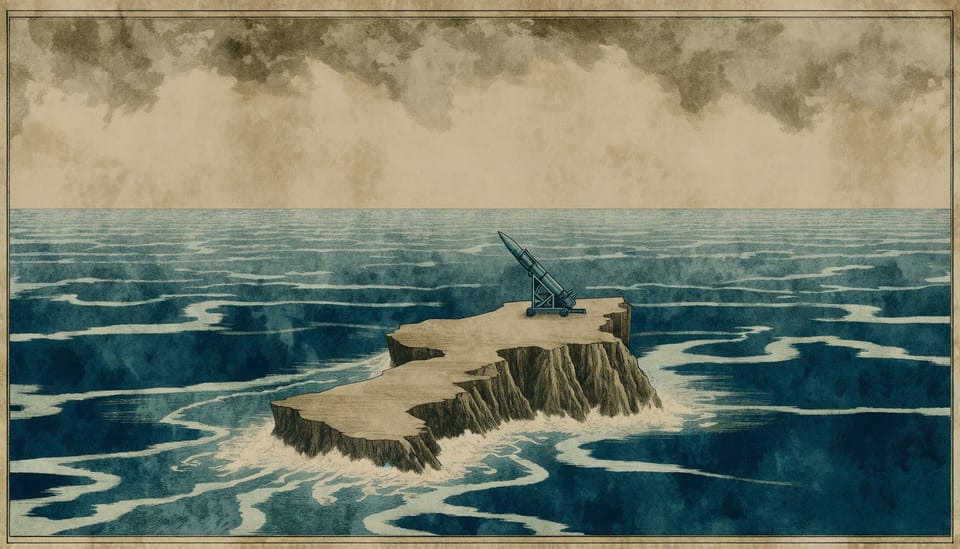

China's maritime militia can strangle Taiwan's economy without firing a shot. The island's military has tools to respond—but every option risks the escalation Taipei desperately wants to avoid. In the narrow space between capitulation and catastrophe, Taiwan must find a path that may not exist.

🎧 Listen to this article

The Floating Cordon

China’s maritime militia presents Taiwan with a problem that no military manual adequately addresses. The vessels look like fishing boats. Their crews hold fishing licenses. They carry no visible weapons. Yet when hundreds of them converge on Taiwan’s waters in coordinated formations, they function as an instrument of state coercion as effective as any warship—and far harder to counter without appearing the aggressor.

This is the essence of gray-zone warfare: coercion calibrated to remain just below the threshold that would justify a military response. Taiwan’s challenge is not whether it can sink Chinese vessels. It can. The question is whether it can break a quasi-blockade without handing Beijing the narrative victory of “Taiwanese aggression” that might justify the very escalation Taipei seeks to avoid.

The answer is uncomfortable. Taiwan possesses tools to contest militia pressure, but each carries escalation risks that compound with use. The island’s best options lie not in dramatic confrontation but in the patient accumulation of advantages: better surveillance, faster response times, international legitimacy, and economic resilience. None of these guarantee success. All of them buy time—and time, in this contest, may be the most valuable currency of all.

What a Militia Blockade Actually Looks Like

Forget the cinematic image of warships enforcing a declared blockade. China’s maritime militia operates through a different logic entirely. The People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia—what Andrew Erickson of the Naval War College calls China’s “third sea force”—consists of fishing vessels that double as instruments of state power. Some are purpose-built militia craft; others are ordinary fishing boats recruited through government subsidies. All operate under PLA command while maintaining the appearance of civilian activity.

The 2012 Scarborough Shoal standoff demonstrated the model. Chinese fishing vessels, backed by coast guard ships, occupied waters claimed by the Philippines. Manila’s navy withdrew after a diplomatic standoff. The fishermen stayed. A decade later, the Philippines still cannot access the shoal.

Taiwan would face a more sophisticated version. Hundreds of vessels converging on shipping lanes. Not blocking ports directly—that would constitute a formal blockade under international law, requiring declaration and enforcement. Instead, creating what might be called a “flotilla of inconvenience”: vessels that impede navigation, crowd anchorages, and force commercial ships to choose between costly delays and risky passage through congested waters.

The effect would be economic strangulation without the legal clarity of blockade. Taiwan imports 98% of its energy by sea. Its semiconductor industry—the island’s strategic crown jewel—depends on continuous flows of chemicals, gases, and equipment. A militia presence that merely slows shipping would cascade through supply chains within weeks.

Insurance markets would accelerate the damage. War risk premiums for Taiwan Strait transits would spike the moment militia vessels massed in commercial lanes. Shipping companies, already operating on thin margins, would reroute or suspend service. The blockade would become self-enforcing through commercial calculation rather than naval firepower.

This is the strategic elegance of militia operations. They achieve coercive effect while preserving deniability. Beijing can claim its fishermen are merely exercising traditional fishing rights. Any Taiwanese response that damages a “civilian” vessel becomes an act of aggression. The burden of escalation shifts to the defender.

Taiwan’s Toolkit and Its Limits

Taiwan is not defenseless. Its Coast Guard Administration operates 139 vessels over 20 tons, and the service has developed new rules of engagement for what officials delicately term “unscripted combat scenarios.” The navy fields 36 missile boats capable of rapid response. Shore-based Harpoon anti-ship missiles provide a credible deterrent against any escalation to conventional naval combat.

The problem is not capability but calibration. Every response option carries escalation risk.

Water cannons and non-lethal measures can disperse individual vessels but prove ineffective against mass formations. When hundreds of boats operate in coordinated patterns, dispersing one merely shifts the problem. The militia’s numerical advantage overwhelms point responses.

Ramming or shouldering—the physical jostling that coast guards worldwide use against intruders—works in isolated incidents. Against a militia trained in close-quarters harassment, it invites the very collisions that could provide Beijing with propaganda footage of “Taiwanese aggression.” Human fatigue compounds the risk. Research on maritime accidents shows that fatigued crews exhibit degraded judgment precisely when split-second decisions matter most.

Arresting militia crews sounds satisfying but creates its own problems. Detaining fishermen who claim civilian status forces Taiwan into a legal thicket. Are they prisoners of war? Criminal suspects? Unlawful combatants? Each classification carries different obligations under international law. Mass detentions would strain Taiwan’s judicial system while providing Beijing with hostages for diplomatic leverage.

Lethal force remains the ultimate option and the most dangerous. Taiwan’s navy could sink militia vessels. Doing so would cross a threshold from which retreat becomes impossible. Beijing’s domestic nationalism—already a constraint on Chinese leadership flexibility—would demand response. The militia’s very expendability makes it useful precisely because losing vessels costs China little while forcing Taiwan to bear the moral and diplomatic burden of killing “fishermen.”

This asymmetry defines Taiwan’s dilemma. Every effective response risks escalation. Every restrained response accepts erosion.

The Escalation Ladder’s Missing Rungs

Classical escalation theory, developed for nuclear standoffs, assumed clear thresholds between peace and war. Herman Kahn’s famous ladder had 44 rungs, each representing a distinct level of conflict intensity. Gray-zone operations exploit the gaps between rungs.

The militia blockade occupies a space that international law struggles to categorize. Under the San Remo Manual on armed conflict at sea, merchant vessels lose protected status only when they directly participate in hostilities. Fishing boats that merely obstruct navigation exist in legal limbo. They are not combatants, but neither are they innocent passage.

This ambiguity is a feature, not a bug. Beijing’s strategists understand that Western legal frameworks create exploitable seams. The U.S. Naval Institute has noted that “China’s maritime militia often acts in ways consistent with either piracy or naval forces”—a deliberate blurring that paralyzes response.

Taiwan faces what might be termed the “first-mover disadvantage.” Whoever escalates first bears the narrative cost. A Taiwanese vessel that fires on a militia boat—even in self-defense—becomes the aggressor in Beijing’s telling. International audiences, unfamiliar with the militia’s military command structure, see fishing boats attacked by naval vessels. The optics favor China regardless of the underlying reality.

The escalation dynamics grow more dangerous with duration. Prolonged confrontation exhausts crews, depletes supplies, and accumulates grievances. Minor incidents—a collision, a crew member lost overboard, a mechanical failure in congested waters—can cascade into crises that neither side intended. Research on allostatic load shows that sustained stress degrades decision-making, increasing the probability of miscalculation precisely when precision matters most.

The International Dimension

Taiwan cannot win this contest alone. Its strategic position depends on convincing outside powers—particularly the United States and Japan—that intervention serves their interests.

The Taiwan Relations Act provides the legal framework but not the commitment. Washington must “determine, in accordance with constitutional processes, appropriate action” in response to threats against Taiwan. That language permits everything from diplomatic protest to military intervention. It guarantees nothing.

A militia quasi-blockade tests American resolve in uncomfortable ways. Unlike a Chinese naval attack—which would trigger clear alliance obligations—the slow strangulation of Taiwan’s economy offers no obvious intervention point. When does harassment become blockade? When does blockade become act of war? The ambiguity that protects Beijing also paralyzes Washington.

Japan faces similar constraints with additional complications. U.S. forces operating from Japanese bases would require Tokyo’s consent. That consent depends on domestic politics shaped by Okinawan sovereignty concerns and war-weariness. A militia operation that avoids clear military confrontation may not meet Japanese thresholds for supporting American intervention.

The allies’ dilemma mirrors Taiwan’s. Doing too little invites Chinese success. Doing too much risks the broader war everyone claims to want to avoid. Beijing’s strategists have studied this dynamic carefully. The militia exists precisely to exploit it.

The Temporal Dimension

Time operates differently for each party. China can sustain militia pressure indefinitely. The vessels require minimal logistics. Crews rotate through fishing communities accustomed to long deployments. The economic cost to Beijing is trivial compared to the strategic gains.

Taiwan operates under compression. Energy reserves, food supplies, and semiconductor production inputs all have finite buffers. The island’s economic resilience depends on continuous flows that even partial disruption would interrupt. Weeks of quasi-blockade could accomplish what months of formal blockade might not.

This temporal asymmetry shapes strategic options. Taiwan’s best moves are those that extend its endurance while raising China’s costs. Stockpiling critical supplies. Diversifying shipping routes. Pre-positioning inventory in third-country facilities. None of these prevent a blockade, but they buy the time necessary for international response to coalesce.

The danger is that preparation itself becomes provocation. Taiwan’s stockpiling efforts are simultaneously interpreted by PLA planners as evidence of war preparation. Measures intended to reassure Taiwanese citizens signal to Beijing that Taipei anticipates conflict—potentially accelerating the timeline China’s leadership might otherwise defer.

This is the paradox of deterrence in the gray zone. Strength invites testing. Weakness invites aggression. The narrow path between requires calibration that no doctrine adequately captures.

What Actually Works

Taiwan’s most effective responses avoid the kinetic entirely. They operate in domains where the militia’s numerical advantage cannot translate into coercive effect.

Maritime domain awareness represents the critical first investment. Taiwan cannot respond to what it cannot see. The island’s radar coverage, satellite access, and signals intelligence capabilities determine whether militia movements can be tracked, classified, and anticipated. Knowing that 200 vessels are converging on a shipping lane twelve hours before they arrive transforms the response calculus.

Information operations matter as much as naval operations. The militia’s effectiveness depends on maintaining the fiction of civilian status. Documenting command relationships, intercepting communications, and publicizing the military nature of “fishing” activities erodes the deniability that makes gray-zone tactics attractive. Every militia vessel photographed receiving instructions from PLA officers is a vessel that becomes harder to deploy without international cost.

Economic resilience provides strategic depth. Taiwan’s semiconductor industry gives the island leverage that pure military calculations miss. A blockade that disrupts chip production harms China’s own technology sector and triggers global supply chain crises. This interdependence is not a vulnerability but a form of deterrence—provided Taiwan can survive long enough for the economic pain to register in Beijing.

Legal warfare—what Chinese strategists call “lawfare”—cuts both ways. Taiwan can invoke international maritime law, environmental regulations, and fishing agreements to constrain militia operations. Environmental crimes like coral reef destruction by militia vessels provide grounds for international prosecution. The legal arena offers asymmetric advantages to the defender willing to exploit them.

None of these responses is decisive. All of them accumulate advantage over time. The contest is not a single battle but a campaign of attrition in which the side that maintains coherence longest prevails.

The Unspoken Variable

Every analysis of Taiwan’s options must acknowledge what cannot be calculated: the role of chance, miscalculation, and human decision under pressure.

A militia captain, exhausted after days at sea, misjudges distance and rams a Taiwanese coast guard vessel. A Taiwanese sailor, nerves frayed by harassment, fires a warning shot that strikes a Chinese crewman. A typhoon scatters both formations, creating confusion that one side interprets as attack. The scenarios multiply endlessly.

Gray-zone warfare assumes rational actors calibrating responses to avoid escalation. History suggests that assumption is optimistic. Wars begin through miscalculation as often as intention. The very ambiguity that makes militia operations attractive also makes them unpredictable. Neither Beijing nor Taipei fully controls the forces they deploy.

This uncertainty is not an argument for paralysis. It is an argument for building systems resilient to failure—response protocols that degrade gracefully, communication channels that survive crisis, and decision-making structures that can absorb shock without shattering.

Taiwan’s military can contest a militia blockade. Whether it can do so without triggering the broader conflict both sides claim to fear depends less on capability than on wisdom—and wisdom, in the fog of gray-zone confrontation, is the scarcest resource of all.

FAQ: Key Questions Answered

Q: Could Taiwan legally fire on Chinese fishing vessels conducting a quasi-blockade? A: International law permits defensive action against vessels participating in hostilities, but the militia’s civilian appearance complicates legal justification. Taiwan would need to demonstrate military command relationships—possible but diplomatically costly—before lethal force could be defended internationally.

Q: How long could Taiwan sustain essential imports under a partial blockade? A: Taiwan maintains strategic petroleum reserves of approximately 90-120 days and has been expanding stockpiles of critical materials. However, semiconductor production depends on continuous chemical and gas supplies with much shorter buffers, potentially measured in weeks rather than months.

Q: Would the United States intervene in a militia-only blockade scenario? A: The Taiwan Relations Act requires the President and Congress to determine “appropriate action” but does not mandate military response. A quasi-blockade that avoids clear acts of war would test American resolve and likely produce diplomatic and economic responses before military ones.

Q: What distinguishes China’s maritime militia from ordinary fishing fleets? A: Militia vessels operate under PLA command, receive government subsidies for construction and operations, conduct coordinated training exercises, and perform surveillance and harassment missions on behalf of state objectives—while maintaining the legal status of civilian fishing vessels.

The Narrow Strait

Taiwan’s predicament admits no clean solution. The island cannot match China’s capacity for sustained gray-zone pressure. It cannot ignore that pressure without accepting gradual strangulation. It cannot respond forcefully without risking the escalation it seeks to avoid.

What remains is the patient work of building resilience, documenting aggression, and maintaining the international relationships that give Taiwan’s resistance meaning beyond its shores. The militia blockade is not a problem to be solved but a condition to be managed—indefinitely, carefully, and with clear eyes about the stakes.

The Taiwan Strait has been called the most dangerous waterway in the world. That danger lies not in the weapons that might be used but in the ambiguity that makes their use both possible and catastrophic. In this narrow passage between peace and war, Taiwan must navigate without maps, against currents it did not choose, toward a destination no one can guarantee.

The voyage will be long. The only certainty is that stopping is not an option.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- Understanding China’s Third Sea Force: The Maritime Militia - Andrew Erickson’s foundational research on PAFMM structure and operations

- The Law of Naval Warfare and China’s Maritime Militia - Naval War College analysis of legal frameworks governing militia activities

- China’s Maritime Militia and Fishing Fleets: A Primer for Operational Staffs - Military Review assessment of tactical implications

- The Navy Needs a Gray-Zone Strategy - U.S. Naval Institute analysis of response options

- CSIS China Power: Could China Blockade Taiwan? - Comprehensive assessment of blockade scenarios and Taiwan’s vulnerabilities

- San Remo Manual on International Law Applicable to Armed Conflicts at Sea - International Committee of the Red Cross legal framework

- Gray Zone Threats to Undersea Infrastructure - Analysis of infrastructure vulnerabilities in gray-zone scenarios