Why Gulf states are urging America not to strike Iran

Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and their neighbours have spent decades under an American security umbrella. Now they are begging Washington to keep that umbrella closed—fearing they would pay the price for any attack on Tehran.

🎧 Listen to this article

The Paradox of Proximity

Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and their Gulf neighbours have spent decades purchasing American weapons, hosting American bases, and sheltering under an American security umbrella. Yet when President Trump threatens military strikes against Iran—the very adversary this architecture was designed to deter—these same states are quietly begging Washington to stand down.

This is not ingratitude. It is survival arithmetic.

The Gulf monarchies understand something that Washington’s Iran hawks do not: they would bear the costs of any American military adventure while gaining almost nothing from it. Their oil terminals, desalination plants, and glass-skinned cities lie within range of Iranian missiles. Their economies depend on the Strait of Hormuz remaining open. Their populations include millions of Shia Muslims whose loyalties become complicated when American bombs fall on Persian soil.

The pressure campaign is real. CBS News reports that Saudi Arabia, Oman, and Qatar are engaged in “intensive diplomacy between Iran and the United States, aiming to stave off a military conflict.” Arab Gulf officials have delivered explicit messages urging Washington to “refrain from strikes on Iran, citing the region’s security and economic vulnerabilities.” This is not hedging. It is a calculated bet that managed tension serves Gulf interests better than American victory.

Geography as Destiny

A map explains the Gulf states’ predicament better than any diplomatic cable. The Strait of Hormuz is twenty-one miles wide at its narrowest point. Through this chokepoint flows roughly twenty percent of the world’s oil. Iran controls the northern shore. Oman controls the southern. Every tanker leaving Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Kuwait, or Qatar must pass within range of Iranian anti-ship missiles.

The numbers are unforgiving. Saudi Arabia exports approximately seven million barrels of oil daily. The UAE exports around three million. Kuwait adds another two million. A sustained closure of the Strait—even a partial one achieved through mine-laying and harassment—would remove a quarter of global oil supply from the market within days.

Iran need not close the Strait to devastate Gulf economies. It merely needs to make insurers nervous. War risk premiums for vessels transiting the Strait of Hormuz have already begun climbing as tensions escalate. Shipping surcharges surge with each new threat. The mechanism is elegant in its cruelty: Iran can impose costs on its neighbours simply by appearing dangerous, without firing a shot.

The 2019 attacks on Saudi Arabia’s Abqaiq oil processing facility demonstrated the vulnerability with brutal clarity. Drones and cruise missiles, launched from Yemen or perhaps Iran itself, struck the world’s largest oil processing plant. Saudi air defences—American-made Patriot batteries—failed to intercept them. Production dropped by half overnight. The kingdom that had spent billions on American weapons discovered that those weapons could not protect its most valuable infrastructure from its most dangerous enemy.

That lesson has not been forgotten in Riyadh.

The Hostage Economy

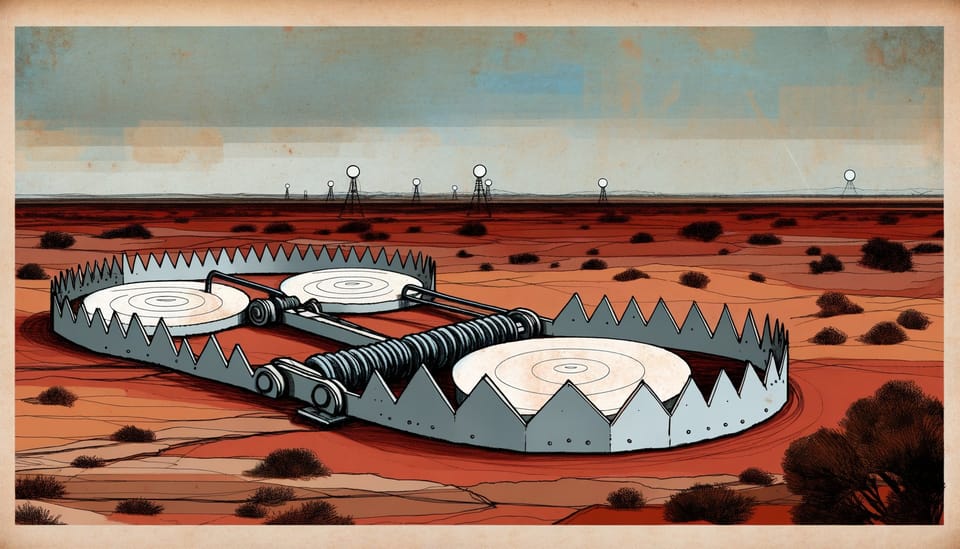

Gulf states have built economies that function brilliantly in peacetime and collapse instantly in war. Dubai’s skyline—all glass and steel and architectural ambition—represents perhaps the world’s most expensive hostage.

Consider desalination. Saudi Arabia derives roughly seventy percent of its drinking water from desalination plants clustered along its Gulf coast. The UAE is even more dependent. These facilities are large, fixed, and impossible to harden against determined attack. A single Iranian missile striking a major desalination plant would create a humanitarian crisis within days. Cyber attacks offer an even more insidious threat: the vulnerability of desalination infrastructure to digital sabotage has kept Gulf security planners awake at night for years.

The expatriate workforce compounds the fragility. Foreigners constitute roughly ninety percent of the UAE’s private sector workforce and similar proportions across the smaller Gulf states. These workers have no patriotic obligation to remain during a crisis. War risk triggers evacuation clauses in corporate contracts. The first ten percent of expatriates leaving could trigger a cascade, with the next thirty percent fleeing and collapsing the economic model that sustains Gulf prosperity.

This is not speculation. It is the scenario that Gulf planners run in their war games—and the scenario they desperately wish to avoid.

The Iranian Calculus

Tehran understands Gulf vulnerability as well as Riyadh does. Iranian strategic doctrine explicitly targets the economic foundations of American allies rather than their military forces. Why attack a heavily defended American base when you can strike an undefended water treatment plant?

Iran’s proxy network extends this reach. Hezbollah in Lebanon, the Houthis in Yemen, various Shia militias in Iraq—each represents a potential vector for retaliation that offers Tehran plausible deniability. The Houthis have already demonstrated their ability to strike deep into Saudi territory with drones and ballistic missiles. A full-scale American attack on Iran would almost certainly trigger a coordinated response across multiple fronts.

The uncertainty itself is a weapon. Gulf security services struggle to distinguish between Iranian-controlled proxies and autonomous actors operating within Iranian strategic guidance. This ambiguity creates planning impossibility: how do you defend against threats you cannot precisely identify?

Iranian strategic culture adds another layer of complexity. Twelver Shia eschatology emphasizes patient suffering and eventual vindication, enabling multi-decade resistance strategies that outlast American attention spans. Iran can absorb punishment that would collapse other regimes because its leaders genuinely believe time favours them.

The American Alliance Dilemma

Gulf states want American protection without American wars. This is not hypocrisy—it is the rational preference of any small state dependent on a great power patron.

The security architecture is extensive. The United States maintains significant military presence across the Gulf: Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar hosts the largest American military facility in the Middle East. Bahrain hosts the Fifth Fleet. The UAE, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia all host American forces under various arrangements. Status of Forces Agreements govern the legal framework for this presence.

These bases create mutual dependency. America needs them for power projection across the Middle East and into Central Asia. Gulf states need the implicit security guarantee they represent. But the guarantee has always been ambiguous: does hosting American forces mean automatic American defence, or does it mean becoming a target in American wars?

The 2023 Comprehensive Security Integration and Prosperity Agreement between the United States and Bahrain promised enhanced cooperation across defence, technology, and investment. Similar arrangements bind other Gulf states to Washington. Yet these agreements do not obligate America to defend Gulf territory, and they do not obligate Gulf states to support American offensive operations.

This ambiguity is a feature, not a bug. It allows both sides to claim the relationship they prefer while avoiding the commitments they fear.

The China Factor

Beijing’s growing presence in the Gulf complicates American calculations and expands Gulf options. China brokered the 2023 Saudi-Iranian rapprochement—a diplomatic achievement that Washington could not have managed and did not attempt.

Chinese investment in Gulf infrastructure has accelerated. China’s LOGINK logistics platform operates in ports across the region, raising concerns about data sovereignty but also creating economic ties that neither Beijing nor Gulf capitals wish to sever. The UAE-China relationship has deepened particularly rapidly, with Emirati leaders visiting Beijing and signing technology cooperation agreements that make Washington nervous.

Gulf states are not choosing China over America. They are hedging—building relationships with both powers to maximize their leverage with each. This strategy requires avoiding conflicts that would force them to choose sides.

An American attack on Iran would be exactly such a conflict. China would face pressure to support Tehran. Gulf states would face pressure to support Washington. The careful balance that allows them to profit from both relationships would collapse.

The Economic Entanglement

Iran and the Gulf states are not merely adversaries. They are also trading partners.

The UAE serves as Iran’s primary commercial window to the world. Despite American sanctions, Dubai remains a hub for Iranian trade—some legal, some less so. Diaspora entrepreneurs exploit the gaps between sanctioned Iran and open Gulf markets, pricing in “manageable” tension as part of their business model.

Qatar shares the world’s largest natural gas field with Iran. The South Pars/North Dome reservoir straddles the maritime boundary between the two countries. Qatari gas production from this field has made it the world’s wealthiest nation per capita. Any conflict that damages the shared reservoir—or that gives Iran reason to dispute extraction rights—threatens Qatar’s entire economic model.

The first meeting in ten years between UAE and Iranian economic officials, held in May 2024, produced agreements to establish joint technical task forces and explore cooperation in tourism, trade, energy, and industry. This is not the behaviour of states preparing for war. It is the behaviour of states investing in peace.

The Domestic Calculation

Gulf rulers fear their own populations almost as much as they fear Iranian missiles.

Bahrain’s population is majority Shia, ruled by a Sunni monarchy. Saudi Arabia’s oil-rich Eastern Province contains a significant Shia minority. The UAE includes Iranian-origin communities with family ties across the Gulf. An American attack on Iran would inflame sectarian tensions that Gulf security services spend enormous resources suppressing.

The social contract in Gulf monarchies exchanges political quiescence for economic prosperity. Citizens accept limited political participation in return for subsidies, jobs, and services. War disrupts this bargain. Economic shocks increase entropy faster than subsidies can respond. The rentier state model that has sustained Gulf monarchies for decades cannot pivot from “provider of luxury” to “demander of sacrifice” without triggering a legitimacy crisis.

Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman has staked his political future on Vision 2030—an ambitious economic diversification programme that requires foreign investment, tourism, and regional stability. War with Iran would destroy all three. The prince who has centralised power more thoroughly than any Saudi ruler in generations would bear personal responsibility for the failure.

The Path of Least Resistance

Gulf states are not pacifists. They have funded proxy wars, intervened militarily in Yemen, and supported regime change across the Arab world. Their objection to American strikes on Iran is not moral—it is practical.

They prefer managed tension. A hostile Iran that remains contained serves Gulf interests better than either a defeated Iran or an unleashed one. Containment allows them to justify American military presence, maintain domestic security narratives, and avoid the catastrophic costs of actual war.

The ideal outcome for Riyadh and Abu Dhabi is an Iran that remains threatening enough to keep American attention focused on the Gulf, but not threatening enough to trigger American action that would destroy Gulf infrastructure in the crossfire.

This is a delicate balance. It requires constant diplomatic effort to restrain both Iranian provocations and American responses. It requires maintaining relationships with Tehran even while publicly condemning Iranian behaviour. It requires telling Washington what it wants to hear while quietly undermining policies that might lead to war.

Oman has played this mediating role for decades. Omani diplomacy has facilitated confidential discussions between American and Iranian officials during periods of maximum tension. Sultan Qaboos, and now Sultan Haitham, have positioned their country as the Gulf’s honest broker—trusted by both sides precisely because Oman threatens neither.

Qatar’s hosting of American forces while maintaining dialogue with Iran follows similar logic. The Al Udeid base makes Qatar indispensable to American military planning. The relationship with Tehran makes Qatar useful as a back channel. Neither relationship is comfortable, but both are necessary.

What Happens Next

The current tension will likely resolve without American strikes—not because Washington has been persuaded by Gulf arguments, but because the costs of action exceed the benefits.

Iran’s domestic protests, which prompted Trump’s threats, will either succeed or fail on their own terms. American military intervention would not help protesters; it would allow the Iranian regime to rally nationalist sentiment against foreign aggression. The 1953 playbook—in which American intervention toppled an Iranian government—is not available in 2025.

Gulf states will continue their dual-track approach: public alignment with American security frameworks, private pressure against American military action. They will deepen economic ties with Iran while maintaining the diplomatic fiction of hostility. They will court Chinese investment while assuring Washington of their commitment to the alliance.

This is not a stable equilibrium. It is a managed instability that could collapse under pressure from any direction. An Iranian miscalculation, an American domestic political shift, an Israeli strike that forces American involvement—any of these could trigger the conflict that Gulf states are desperately trying to avoid.

But for now, the Gulf monarchies have made their choice clear. They built their glittering cities on the assumption of American protection without American wars. They are not willing to sacrifice those cities to test whether the assumption was correct.

FAQ: Key Questions Answered

Q: Why don’t Gulf states simply support US strikes if Iran is their main adversary? A: Gulf states would suffer the immediate consequences of Iranian retaliation—missile strikes on oil facilities, disrupted shipping, potential attacks on desalination plants—while gaining little from Iranian regime change. Their proximity makes them hostages to any conflict, regardless of which side they support.

Q: Could Iran actually close the Strait of Hormuz? A: A complete closure would be difficult to sustain against American naval power, but Iran does not need to close the Strait entirely. Mine-laying, harassment of tankers, and attacks on port facilities would spike insurance premiums and shipping costs, effectively taxing Gulf exports without a formal blockade.

Q: What role does China play in Gulf states’ calculations? A: China offers Gulf states an alternative economic partner and diplomatic channel that reduces their dependence on Washington. The 2023 China-brokered Saudi-Iran agreement demonstrated Beijing’s growing influence. Gulf states use this relationship as leverage with America while avoiding commitments that would force them to choose between the two powers.

Q: Are Gulf states genuinely afraid of Iran, or is the threat exaggerated? A: The threat is real but manageable under current conditions. Gulf states have invested heavily in missile defence and maintain significant military capabilities. Their fear is not of Iranian invasion but of Iranian retaliation—specifically, attacks on economic infrastructure that would be difficult to defend and catastrophic to absorb.

The Weight of Glass Cities

The Gulf states’ message to Washington carries an uncomfortable truth: American military power cannot protect everything Americans value in the region. The bases, the oil flows, the investment relationships, the diplomatic partnerships—all depend on a stability that American strikes would shatter.

This is the paradox of proximity. The closer you build to danger, the more you need protection. The more protection you need, the more you fear the protector’s wars. Gulf rulers have built extraordinary wealth on extraordinary vulnerability. They are asking America to remember that their cities, unlike American cities, lie within range of Iranian missiles.

It is a reasonable request. Whether Washington will honour it depends on calculations that have little to do with Gulf preferences—and everything to do with American domestic politics, Israeli security concerns, and the unpredictable decisions of leaders in Tehran. The Gulf states can pressure. They cannot control.

Their glass towers will wait, glittering in the desert sun, for an answer that may never come.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- CBS News investigation on Gulf diplomatic efforts - primary reporting on Saudi, Omani, and Qatari pressure on Washington

- Saxo Bank analysis of Hormuz risk premiums - oil market dynamics and shipping cost escalation

- ScienceDirect simulation study - modelling of US-Iran war impacts on global oil prices

- TraCCC report on Dubai as trade hub - documentation of UAE-Iran commercial ties despite sanctions

- UAE Ministry of Economy statement - official record of UAE-Iran economic committee meeting

- US State Department SOFA documentation - legal framework for American military presence

- CFR Global Conflict Tracker - timeline of US-Iran confrontations

- State Department security agreement - US-Bahrain Comprehensive Security Integration and Prosperity Agreement