Why Australia cannot stay neutral in a US-China war

Australia hosts US military facilities so critical to American warfighting that Beijing would likely strike them in any serious conflict. The infrastructure that makes Australia valuable to Washington also makes it a target—and unlike the United States, Australia cannot absorb the consequences.

🎧 Listen to this article

The Facilities That Cannot Be Moved

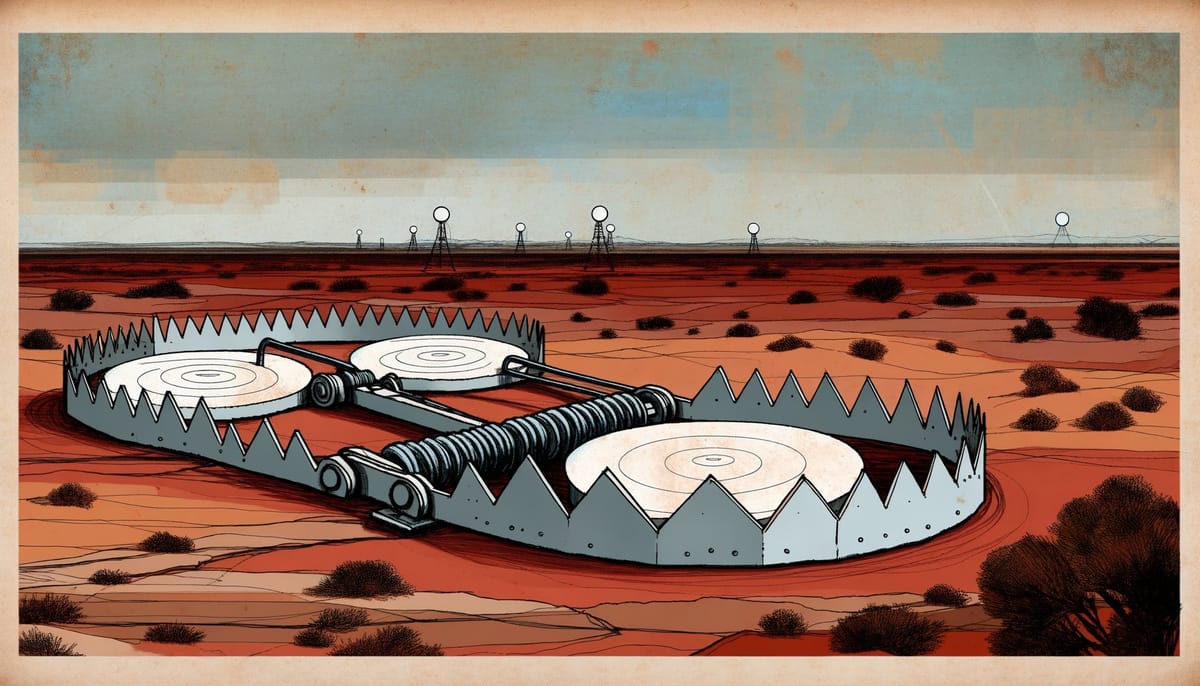

Pine Gap sits in the red centre of Australia, 19 kilometres southwest of Alice Springs, in a landscape so flat and quiet that the radomes seem to hover like white bubbles against the ochre earth. Few Australians have seen it. Fewer still understand what it does. Yet this installation—jointly operated by the CIA, NSA, and Australian intelligence services—controls geosynchronous SIGINT satellites covering more than half the planet’s surface outside polar regions. It provides real-time targeting data for US precision strikes. It tracks ballistic missiles from launch to impact. And it makes Australia, in any serious conflict between the United States and China, a target.

This is not speculation. It is geometry.

The question is not whether Australia would be drawn into a US-China war. The question is whether Australia could stay out of one—and the answer, buried in treaty language and satellite coverage maps and the physics of electromagnetic propagation, is almost certainly no.

The Architecture of Entanglement

Australia hosts a constellation of US military facilities that cannot be replicated elsewhere. This is not hyperbole dressed as analysis. It is a function of geography, physics, and decades of investment that created infrastructure with no practical substitute.

Consider the specifics. Pine Gap’s position at 23.8° south latitude enables satellite coverage from 60° east to 153° west longitude—a swath encompassing the entire Indo-Pacific, the Middle East, and the eastern Indian Ocean. Move the facility north to Guam and you lose coverage of critical areas. Move it to Diego Garcia and you sacrifice the geometric relationship that makes real-time tracking possible. The installation exists where it does because that is where it must be.

The Naval Communication Station Harold E. Holt at North West Cape operates with 1.8 million watts of radiated power, enabling one-way broadcasts to submarines that need not surface to receive orders. In a conflict where US ballistic missile submarines might need to launch on command, this facility provides the communication link. The Deep Space Advanced Radar Capability (DARC), planned for Western Australia, exploits the continent’s infrared silence—the absence of urban heat signatures and electromagnetic noise that makes certain observations impossible in more developed regions.

These facilities share a common characteristic: they require Australia’s specific geography. The southern hemisphere position, the continental scale, the distance from potential adversaries, the tectonic stability that enables precise calibration—these cannot be purchased or constructed elsewhere. As one Nautilus Institute analysis documents, Pine Gap’s satellite control functions depend on its exact location in ways that make relocation impractical within any relevant timeframe.

The result is a form of strategic dependency that flows in both directions but weighs differently on each partner.

Why Neutrality Has Already Been Foreclosed

The conventional understanding of alliance obligations treats them as choices. Australia could, in theory, invoke ANZUS provisions requiring consultation rather than automatic assistance. Article IV of the treaty states that each party “recognizes that an armed attack in the Pacific Area on any of the Parties would be dangerous to its own peace and safety and declares that it would act to meet the common danger in accordance with its constitutional processes.” This language—deliberately softer than NATO’s Article 5—preserves formal sovereignty over the decision to fight.

The problem is that formal sovereignty and practical sovereignty have diverged.

When a Chinese military planner examines the kill chain for a US precision strike, that planner sees Australian facilities as integral components. Pine Gap provides the targeting data. North West Cape transmits the launch orders. The space situational awareness installations track Chinese satellites that might otherwise provide warning. From Beijing’s perspective, these facilities are not neutral infrastructure that happens to sit on Australian soil. They are American weapons systems with Australian addresses.

International law supports this interpretation. The 1907 Hague Convention V established that neutral states cannot “avail himself of his neutrality” if they “commit acts in favor of a belligerent.” Modern legal scholarship extends this principle: a neutral state’s failure to prevent belligerent use of its territory may lead to recognition of belligerency against it. Australia cannot simultaneously host facilities that enable US strikes and claim protection as a non-combatant.

This creates what might be called imputed belligerency—a status that attaches not through Australia’s choices but through the function of its infrastructure. The moment US forces use Pine Gap data to guide a missile toward a Chinese target, Australia becomes a co-belligerent in Chinese strategic calculus regardless of what Canberra declares.

The 2014 Force Posture Agreement formalised this arrangement. It grants US forces “unimpeded access and operational control” over agreed facilities for “training, transit, refueling, maintenance, prepositioning of equipment/materiel, and deployments.” Australia retains ownership and primary security responsibility—the flag flies over the gate—but operational control in wartime rests with American commanders pursuing American objectives.

The Asymmetry of Consequences

Here is where the strategic mathematics become unforgiving for Australia in ways they simply are not for the United States.

The United States spans a continent. Its population disperses across 9.8 million square kilometres. Its industrial base, while concentrated in certain regions, maintains redundancy across multiple states. A strike on Pine Gap eliminates a valuable intelligence asset. A strike on Los Angeles ends a civilisation.

Australia’s geography inverts this logic. The country’s population clusters along a coastal ribbon, with Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Perth, and Adelaide containing the overwhelming majority of economic activity and human settlement. Australia’s defence planners acknowledge that the nation is “no longer insulated by its strategic geography” as modern technologies erode the protective value of distance.

Consider the targeting calculus from Beijing’s perspective. In a Taiwan contingency, China faces a choice: accept that Pine Gap will provide real-time intelligence enabling US forces to sink Chinese ships and shoot down Chinese aircraft, or neutralise the facility. The laws of war permit attacks on military objectives. Pine Gap is unambiguously a military objective. A precision strike on the installation would be legally proportionate under most interpretations of international humanitarian law.

The same logic applies to North West Cape, to the DARC installation, to the Submarine Rotational Force-West facilities at HMAS Stirling. Each represents a legitimate military target whose destruction would degrade US warfighting capability. Each sits on Australian soil.

The United States loses intelligence assets. Australia loses sovereignty over whether it is at war.

This asymmetry extends beyond the immediate military dimension. Australia’s economy depends on China in ways the American economy does not. In 2023, China accounted for roughly 30% of Australian exports, with iron ore alone representing a massive share of the bilateral trade relationship. Trade data confirms that China depends heavily on Australian iron ore imports, making up 82.9% of total exports—a mutual dependency that constrains both parties but offers China coercive leverage Australia cannot reciprocate.

The 2020-2021 Chinese trade restrictions demonstrated this vulnerability. Beijing imposed tariffs and informal bans on Australian wine, barley, coal, and other products in response to Canberra’s call for an independent investigation into COVID-19 origins. The restrictions caused billions in economic damage. They also revealed that Australia had no effective countermeasures beyond diplomatic protest and market diversification—a process that takes years, not months.

In a military conflict, economic coercion would intensify. China could halt all trade, freeze Australian assets, pressure third countries to avoid Australian commerce. The United States would face economic disruption; Australia would face economic collapse.

The Escalation Geometry

Chinese military doctrine emphasises what PLA strategists call “system destruction warfare”—the targeting of an adversary’s command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (C4ISR) architecture rather than its combat forces directly. Analysis of PLA doctrine reveals a consistent focus on degrading the information systems that enable US precision strike capability.

Australian facilities sit at the heart of this architecture.

The logic is straightforward. Destroying a US aircraft carrier requires penetrating layered defences with missiles that cost hundreds of millions of dollars and may not succeed. Destroying Pine Gap requires a single precision strike on a fixed target that cannot manoeuvre or shoot back. The cost-exchange ratio overwhelmingly favours attacking the intelligence node rather than the combat platform it enables.

This creates a first-strike incentive that makes Australian facilities particularly vulnerable in the early hours of a conflict. PLA planners examining a Taiwan scenario would recognise that Pine Gap’s targeting data could prove decisive in the opening naval engagements. Waiting to see whether Australia formally enters the conflict cedes a critical advantage. Striking early eliminates the capability before it can be employed.

The US Space Force’s own threat assessments acknowledge that space-based assets face increasing risk from Chinese counter-space capabilities. Ground stations that control those assets face conventional risks. Australia hosts both.

From Canberra’s perspective, this geometry presents an impossible choice. Refusing to allow US use of the facilities in a crisis would rupture the alliance—the very alliance that provides Australia’s ultimate security guarantee. Permitting their use makes Australia a target regardless of its formal belligerent status. The decision has effectively been made in advance by the infrastructure itself.

The Alliance Trap

Alliances are supposed to deter conflict by raising the costs of aggression. Extended deterrence—the promise that an attack on an ally will be treated as an attack on the protecting power—works when adversaries believe the promise. Australia’s strategic position depends entirely on Chinese belief that the United States would defend Australia against retaliation for hosting US facilities.

This belief is not irrational. The United States has substantial interests in maintaining alliance credibility. Abandoning Australia would signal to Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, and other allies that American security guarantees cannot be trusted. The reputational costs would be enormous.

But the belief is also not certain. The United States has never fought a nuclear-armed adversary to defend a treaty ally. The scenarios in which Australia faces Chinese retaliation are precisely the scenarios in which US decision-makers must weigh Australian cities against American cities. Extended deterrence works until the moment it is tested.

Survey data suggests growing Australian public ambivalence about the US alliance, with concerns about being drawn into conflicts not of Australia’s choosing competing against fears of abandonment. This ambivalence reflects an accurate reading of the strategic situation: Australia depends on the alliance for security but the alliance itself generates insecurity.

The AUKUS agreement intensifies this dynamic. The $368 billion submarine program—with an additional $122 billion contingency for cost overruns—represents the largest defence acquisition in Australian history. It purchases nuclear-powered submarines that will operate as part of integrated US naval forces in the Indo-Pacific. It deepens interoperability in ways that make independent Australian operations increasingly difficult. And it creates fiscal dependencies that make questioning the alliance politically impossible.

AUKUS is not a submarine deal. It is a sovereignty transfer disguised as a capability acquisition.

What Would Change the Trajectory

Three intervention points exist, though none offers easy solutions.

Geographic diversification of US capabilities could reduce Australian exposure. If the United States invested in alternative facilities—perhaps in the Northern Mariana Islands, in expanded Pacific island partnerships, in space-based systems that reduce dependence on ground stations—the targeting value of Australian installations would diminish. But this would require decades and hundreds of billions of dollars, and would face the same geographic constraints that made Australia attractive initially. Some capabilities cannot be relocated because the physics do not permit it.

Explicit alliance renegotiation could clarify Australian consent requirements for facility use in specific contingencies. The current arrangements grant operational control to US commanders without requiring Australian approval for individual operations. A revised framework might require joint authorisation for strikes launched using Australian-hosted intelligence, or establish scenarios in which Australia could restrict facility access without triggering alliance collapse. But such negotiations would signal doubt about alliance reliability at precisely the moment when deterrence requires certainty. The United States would resist. Australia would face accusations of abandonment.

Regional security architecture development could embed Australian facilities within multilateral frameworks that complicate Chinese targeting calculations. If Pine Gap served not just US forces but a broader coalition including Japan, South Korea, and potentially India, striking it would expand the conflict in ways Beijing might wish to avoid. But multilateralising intelligence facilities raises profound sovereignty and security concerns, and the current trajectory of Indo-Pacific security cooperation does not suggest such arrangements are imminent.

The most likely scenario is continuation of current trends: deepening integration, increasing vulnerability, and persistent hope that deterrence will hold. Australia has sold options on its sovereignty that it cannot buy back.

The Quiet Admission

Australia’s 2023 Defence Strategic Review acknowledged what previous documents obscured: the country faces “the most challenging strategic circumstances since the Second World War.” China’s military buildup proceeds “without transparency or reassurance regarding strategic intent.” The protective value of distance has eroded. The assumptions underlying decades of defence planning no longer hold.

What the review did not say—what no official document can say—is that Australia’s strategic choices have already been made. The facilities exist. The treaties are signed. The submarines are ordered. The integration is too deep to reverse without costs that no government would accept.

This is not a failure of Australian statecraft. It is the predictable outcome of a middle power seeking security through alignment with a great power, in a region where another great power is rising. The logic was sound when the facilities were built. The logic remains sound today. The problem is that sound logic can still produce dangerous outcomes.

Australia has become essential to American warfighting in the Indo-Pacific. This makes Australia valuable to Washington. It also makes Australia a target for Beijing. The value and the vulnerability are inseparable. They are the same thing.

In the red centre of the continent, the radomes of Pine Gap continue their silent work, tracking satellites that track ships that carry missiles that could reshape the Asian order. The facility operates around the clock, staffed by Australians and Americans who rarely discuss the strategic implications of what they do. The implications exist regardless.

The next war in Asia, if it comes, will not ask Australia’s permission to include it.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Could Australia legally refuse to let the US use Pine Gap in a conflict with China? A: Technically, Australia retains sovereignty over facilities on its territory. Practically, the 2014 Force Posture Agreement grants US forces operational control, and refusing access would likely trigger alliance collapse. The legal right exists; the political and strategic space to exercise it does not.

Q: Would China actually strike targets on Australian soil? A: Chinese military doctrine emphasises attacking the information systems that enable US precision strike. Pine Gap and similar facilities are legitimate military targets under international humanitarian law. Whether Beijing would accept the escalation risks is uncertain, but the targeting logic is clear.

Q: Does the ANZUS Treaty require the US to defend Australia if China retaliates? A: ANZUS requires consultation and action “in accordance with constitutional processes”—not automatic defence. Unlike NATO’s Article 5, it preserves discretion. Whether the US would defend Australia depends on circumstances, not treaty language.

Q: What would happen to Australia’s economy in a US-China war? A: China accounts for roughly 30% of Australian exports. A conflict would likely halt bilateral trade entirely, causing immediate economic crisis. Unlike the US, Australia lacks the domestic market depth to absorb such a shock.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- Nautilus Institute analysis of Pine Gap SIGINT satellites - technical assessment of satellite coverage geometry and facility functions

- Naval Communication Station Harold E. Holt documentation - specifications of VLF transmission capabilities

- Australia’s 2023 Defence Strategic Review - official assessment of strategic environment

- Force Posture Agreement text - primary treaty document

- PLA Systems Attack doctrine analysis - National Defense University assessment of Chinese military strategy

- US Space Force threat assessment - official documentation of space domain threats

- Pacific Forum analysis of Australia’s strategic triangle - examination of Australia-US-China dynamics