Australia's alliance dilemma: What happens when the US builds alternatives to Australian bases

The United States is quietly constructing military and intelligence alternatives across the Indo-Pacific that could bypass Australian political constraints in a crisis. Australia risks remaining a target while losing influence over the decisions that make it one.

🎧 Listen to this article

The Phantom Alliance

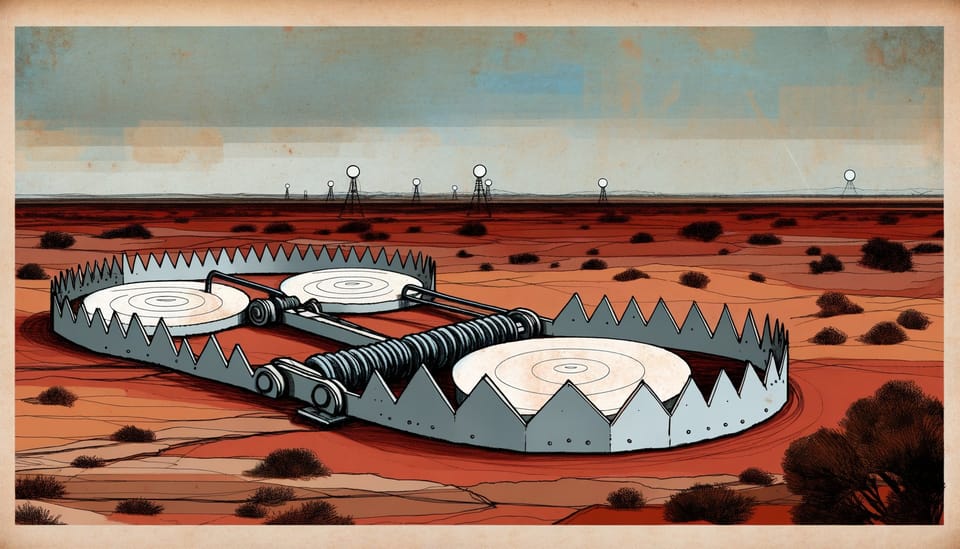

Pine Gap sits in the red dust of Australia’s Northern Territory, 18 kilometres southwest of Alice Springs. The facility’s radomes—white spheres rising from the desert like surveillance mushrooms—track signals across the Indo-Pacific with a precision that makes it irreplaceable. Or so Canberra has long assumed.

The assumption deserves scrutiny. American strategic planners have spent the past decade quietly building what might be called replacement architecture: alternative basing arrangements, intelligence pathways, and logistics networks that could bypass Australian political constraints in a crisis. The Philippines now hosts nine American military sites under an expanded defence cooperation agreement. Japan maintains fourteen US bases. Guam is absorbing a $9 billion military buildup through 2028. The constellation of alternatives grows denser each year.

This presents Australia with a paradox that few in Canberra wish to articulate. The more comprehensively the United States prepares to operate without Australian consent, the more Australia risks becoming what strategic theorists call a “phantom limb”—still attached to the alliance body, still exposed to retaliation, but no longer connected to the nervous system that controls escalation. The brain makes decisions; the limb absorbs consequences.

The parallel is not merely rhetorical. Research on phantom limb pain reveals that maladaptive brain plasticity causes pathology: the reorganisation itself becomes the disease mechanism. Australia’s strategic position may be undergoing similar reorganisation. The alliance architecture is adapting around Australian constraints, and that adaptation could prove more dangerous than the constraints themselves.

The Architecture of Alternatives

Begin with what the United States actually requires from Australia. Three capabilities matter: signals intelligence collection, space-based surveillance, and logistics depth for sustained Indo-Pacific operations. Pine Gap delivers the first two. Darwin’s rotating Marine presence and port access contribute to the third. Everything else—the rhetorical solidarity, the diplomatic alignment, the AUKUS submarines that won’t arrive until the 2030s—is secondary to these operational realities.

Now consider how each could be replicated.

Signals intelligence presents the hardest substitution problem. Pine Gap’s geographic position allows it to monitor satellite communications, detect missile launches, and provide targeting data across a vast arc from the Indian Ocean to the Western Pacific. The facility is classified as a Joint Defence Facility, but the US military, through the National Reconnaissance Office, fully funds and controls it. Australia provides the real estate and the political cover. In exchange, Canberra receives intelligence products whose provenance and completeness it cannot independently verify.

Could this capability move elsewhere? Partially. The United States has expanded ground-based signals collection across the Pacific, including new facilities in Palau and upgraded stations in Japan. Space-based alternatives are proliferating faster. The shift toward low-earth orbit satellite constellations—what one analyst described as “sand mandala architecture” that dissolves and reconstitutes continuously—reduces dependence on any single ground station. The National Reconnaissance Office now operates systems designed for resilience through redundancy rather than concentration.

Logistics substitution is more straightforward. The Pacific Deterrence Initiative received $14.71 billion in congressional authorisation for fiscal year 2024, significantly exceeding the Pentagon’s $9.1 billion request. Much of this funding flows toward distributed basing infrastructure across Micronesia, the Philippines, and Japan. Fuel storage, ammunition prepositions, runway extensions, port upgrades—the physical substrate for sustained operations is spreading across multiple jurisdictions rather than concentrating in any single allied territory.

The pattern suggests deliberate risk distribution. Not abandonment of Australia, but insurance against Australian hesitation.

What Canberra Cannot Control

Australia’s political constraints on crisis participation are real but poorly understood, even within Australia. The constitutional position is stark: there is no requirement for parliamentary approval before the executive commits military forces to operations. The Prime Minister and Cabinet can authorise war without legislative consent. This sounds like maximum flexibility. It isn’t.

The constraint operates through democratic legitimacy rather than legal requirement. Any Australian government committing forces to a Taiwan contingency without broad public support would face political destruction. The Australian Greens have stated they “fundamentally oppose the AUKUS political deal and the outcomes it will have on Australian sovereignty”. Polling shows Australians increasingly perceive the alliance as a constraint on foreign policy independence even while supporting its continuation. This creates a peculiar dynamic: strong alliance support coexisting with deep ambivalence about alliance obligations.

The ANZUS Treaty itself offers less commitment than commonly assumed. Article IV requires each party to “act to meet the common danger in accordance with its constitutional processes.” The phrase was deliberately chosen to avoid automatic intervention obligations. It creates, as one legal scholar noted, “significant political constraints on enforcement.” The treaty is a framework for consultation, not a tripwire for war.

American planners understand this. They have watched Australian governments hedge on Iraq, calibrate involvement in Afghanistan, and maintain studied ambiguity about Taiwan scenarios. The lesson absorbed is simple: Australian participation cannot be assumed, therefore Australian participation cannot be required.

This recognition drives replacement architecture investment. Not as punishment, but as prudence.

The Tempo Problem

Crisis timelines have compressed beyond what democratic deliberation can accommodate. A Taiwan contingency would unfold in hours and days, not weeks and months. Missile flight times measure in minutes. Cyber operations execute in milliseconds. The gap between decision speed and democratic process has become structurally unbridgeable.

Consider what this means for Australian influence. By the time Canberra convenes its National Security Committee, assesses intelligence, debates options, and reaches consensus, the first phase of any major Indo-Pacific conflict would already be decided. Pre-positioned forces would have engaged or not engaged. Targeting data from Pine Gap would have flowed to weapons systems or been routed through alternative channels. The moment for Australian input would have passed.

This is not hypothetical. War powers in the missile age are, as one analyst put it, “functionally irrelevant” because “pre-approved plans, rules of engagement, and machine-speed command and control” determine outcomes before political deliberation begins. Australia’s formal right to consent becomes a phantom right—legally intact but operationally meaningless.

The United States has adapted to this reality by building decision architectures that can function with or without allied political approval. Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2) connects sensors, shooters, and decision-makers across services and nations. The system is designed for speed, not consultation. Australian officers may sit in the command centres, but the architecture does not pause for Australian parliamentary debates.

Targeting Without Influence

Here lies the core asymmetry. Australia remains in the crosshairs regardless of its participation level. Chinese military planners do not distinguish between facilities that Australia controls and facilities that merely sit on Australian soil. Pine Gap processes targeting data. Darwin hosts American Marines. North West Cape communicates with submarines. From Beijing’s perspective, these are American military installations that happen to have Australian flags flying nearby.

The targeting calculus is straightforward. In any serious conflict with the United States, China would face pressure to degrade American intelligence and logistics capabilities across the Indo-Pacific. Australian facilities would be on that target list whether or not Canberra had approved their use, whether or not Australian forces were participating, whether or not the Australian parliament had even convened.

This creates what might be called the phantom limb condition. The limb remains attached to the body and exposed to trauma, but the neural pathways that once connected it to central decision-making have been rerouted. Australia absorbs risk without proportionate influence over the decisions generating that risk.

The condition worsens as replacement architecture matures. Every new facility in the Philippines, every upgraded base in Japan, every additional satellite in the American constellation reduces Washington’s dependence on Australian cooperation. Reduced dependence means reduced leverage. Canberra’s ability to shape American decisions declines precisely as its exposure to the consequences of those decisions remains constant.

Some Australian strategists argue that AUKUS reverses this dynamic—that nuclear-powered submarines will restore Australian relevance and influence. The argument misunderstands the timeline. AUKUS submarines will not enter service until the mid-2030s at earliest. The replacement architecture is being built now. By the time Australia operates its first nuclear-powered submarine, the strategic geometry may have already crystallised around Australian marginality.

The Sovereignty Paradox

A deeper irony operates beneath these strategic calculations. The more Canberra asserts its sovereign right to withhold consent, the more Washington invests in architectures that make Australian consent unnecessary. Australian sovereignty becomes self-limiting: exercising it accelerates the conditions that render it irrelevant.

This resembles what legal theorists call the dormant commerce clause problem in American constitutional law—the negative implications that arise from non-exercise of powers. Australia’s political constraints on base usage may violate an unwritten “dormant alliance clause” that expects reliable access in exchange for security guarantees. The guarantee remains formally intact while the substance hollows out.

The concept of relational sovereignty offers a more productive frame. Sovereignty is not a fixed quantum that one either possesses or surrenders. It exists in relationships, shaped by mutual dependencies and reciprocal constraints. Australia’s sovereignty within the alliance has always been relational—meaningful only to the extent that it could be exercised without triggering American alternatives.

That relational balance is shifting. Not through dramatic rupture, but through quiet infrastructure investment that creates options. The United States is not abandoning Australia. It is preparing for scenarios in which Australia abandons the United States—or more precisely, scenarios in which Australian political constraints prevent timely cooperation.

The Risk Redistribution

What does this mean for Australian security? Three consequences deserve attention.

First, Australia’s deterrence posture weakens. Deterrence depends on adversary beliefs about allied cohesion and response certainty. If China believes that Australian political constraints will delay or prevent American use of Australian facilities, the deterrent value of those facilities declines. Replacement architecture signals that the United States shares this assessment. The signal itself may encourage Chinese risk-taking.

Second, Australia’s escalation influence diminishes. Alliance relationships involve implicit bargaining over when and how to escalate conflicts. Partners with irreplaceable capabilities have more bargaining power than partners with substitutable capabilities. As American alternatives multiply, Australian preferences carry less weight in escalation decisions. Canberra may find itself informed of decisions rather than consulted about them.

Third, Australia’s post-conflict position becomes more precarious. If a major Indo-Pacific conflict occurs and Australia limited its participation due to political constraints, the alliance relationship would face fundamental reassessment. American domestic politics would not forgive an ally that hedged during crisis. But if Australia participated fully despite public ambivalence, the domestic political costs could prove equally severe. Either path leads to diminished Australian autonomy.

The phantom limb metaphor captures this condition precisely. The limb experiences pain from injuries to a body it no longer controls. Cortical reorganisation in phantom limb patients shows that the brain adapts to absent input by remapping neural pathways—but the remapping itself causes chronic pain. Australia may be undergoing analogous strategic reorganisation, adapting to reduced influence while experiencing the persistent pain of undiminished exposure.

What Leverage Remains

Australia is not powerless, but its leverage operates in domains that Canberra has been reluctant to exploit.

Geographic position remains genuinely irreplaceable for certain functions. No amount of alternative basing can replicate Pine Gap’s coverage angles for satellite tracking across the Indian Ocean. The facility’s value is geometric, not just technological. Australia could theoretically leverage this irreplaceability into greater influence over facility operations and intelligence sharing arrangements. It has not done so.

Economic relationships offer another lever. Australia supplies critical minerals essential to American defence manufacturing. Rare earths, lithium, cobalt—the material substrate of advanced weapons systems flows substantially through Australian extraction and processing. This creates interdependence that could translate into strategic influence. Again, Canberra has been hesitant to connect economic and security bargaining.

The most significant lever may be political. Australia shapes American domestic perceptions of Indo-Pacific alliance health. A visible Australian distancing from American strategy would create political problems in Washington that no amount of Philippine or Japanese cooperation could offset. The United States needs Australia to appear committed even if operational alternatives exist. This appearance has value that Australia has not fully monetised.

None of these levers operates automatically. Each requires deliberate Australian strategy that Canberra has been reluctant to articulate, let alone implement. The default trajectory is continued drift toward phantom limb status—formally allied, operationally marginal, strategically exposed.

The Uncomfortable Conversation

Australia faces a choice it has avoided naming. It can accept reduced influence as the price of maintaining political flexibility, understanding that replacement architecture will continue expanding and that Australian preferences will carry diminishing weight in American decisions. Or it can accept reduced flexibility as the price of maintaining influence, committing more explicitly to crisis scenarios and accepting the domestic political costs of that commitment.

What it cannot do is maintain both flexibility and influence simultaneously. The strategic geometry no longer permits that combination. Every Australian hedge incentivises American alternatives. Every American alternative reduces Australian leverage. The cycle is self-reinforcing.

The conversation Australia needs is not about submarines or bases or intelligence sharing arrangements. It is about what kind of ally Australia intends to be, and what risks it is prepared to accept for what benefits. That conversation requires honesty about trade-offs that Australian political culture has systematically avoided.

Pine Gap’s radomes will continue rising from the red dust, tracking signals across the Pacific, feeding data into systems that may or may not pause for Australian consent. The question is whether Australia will remain connected to the decisions those systems enable, or whether it will become what it has always feared: a target without a voice, a partner without influence, a limb that feels pain but cannot move.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Could Australia actually refuse to let the US use Pine Gap in a crisis? A: Legally, yes—Pine Gap operates under a joint agreement that theoretically requires Australian consent for specific operations. Practically, the facility’s command-and-control systems are so integrated with American networks that “consent” becomes a formality. The more relevant question is whether refusal would matter operationally, given expanding American alternatives.

Q: What would China actually target in Australia during a conflict? A: Chinese military doctrine prioritises degrading adversary command, control, communications, and intelligence capabilities. Pine Gap, North West Cape, and Darwin’s military facilities would likely face early attention. Whether China would strike Australian population centres depends on escalation dynamics that no one can predict with confidence.

Q: Does AUKUS change Australia’s strategic position? A: AUKUS submarines will enhance Australian independent capabilities in the 2030s and beyond. They do not address the near-term replacement architecture problem. The submarines may actually reinforce Australian marginality by consuming strategic bandwidth that could otherwise focus on influence-preservation within existing alliance structures.

Q: Is the US actually building alternatives to Australian facilities? A: Yes, though framed as “distributed posture” rather than “replacement.” The $14.71 billion Pacific Deterrence Initiative, expanded Philippine basing, Guam buildup, and proliferated satellite constellations all reduce American dependence on any single allied jurisdiction. Whether this constitutes “replacement” or “redundancy” is largely semantic.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- Privacy International’s Five Eyes Analysis - documentation of intelligence-sharing arrangements and oversight gaps

- Red Flag’s Pine Gap Investigation - detailed examination of facility control and funding structures

- Australian Parliament AUKUS Dissenting Report - documented political opposition to alliance arrangements

- Pentagon Pacific Deterrence Initiative Budget - official documentation of Indo-Pacific infrastructure investment

- JSTOR Relational Sovereignty Analysis - theoretical framework for understanding sovereignty in alliance contexts

- LSU Dormant Commerce Clause Study - legal analysis of negative implications from non-exercise of powers

- JAMA Neurology Phantom Limb Research - foundational research on neural plasticity and maladaptive reorganisation