America's Quiet War in Nigeria

December's airstrikes in Sokoto marked the first direct US military action inside Nigeria. The intervention architecture that produced them was designed to expand. Whether Washington can control what it has started depends on understanding why the Somalia analogy misleads.

The Advisor’s Dilemma

On December 26, 2025, American aircraft struck Islamic State targets in Nigeria’s Sokoto state. The operation was quiet, clinical, and—according to the Pentagon—successful. It was also the first known direct US military strike inside Nigeria. What began as training programs and intelligence sharing had crossed into kinetic action. The question now is not whether America is intervening in Nigeria’s Islamist insurgency, but whether it can stop.

The Somalia parallel haunts Washington’s Africa policy like a phantom limb. Thirty-two years after Black Hawk Down killed eighteen American soldiers in Mogadishu’s streets, the fear of another African quagmire shapes every deployment decision. But the comparison obscures more than it illuminates. Nigeria is not Somalia. The insurgency is different. The state is different. The strategic stakes are different. What remains constant is the structural trap that ensnares every counterterrorism intervention: the gap between what advisors are permitted to do and what the mission requires them to accomplish.

The Insurgency That Isn’t Losing

Boko Haram and its Islamic State-aligned splinter group, ISWAP, have killed tens of thousands and displaced over two million people since 2009. The Nigerian military has declared victory repeatedly. The insurgency persists.

The conventional narrative frames this as a counterterrorism problem: identify extremists, kill them, stabilize the territory. But the Lake Chad Basin defies such linear logic. ISWAP generates approximately $191 million annually through Islamic taxation—ten times the revenue of Borno State’s government. This is not a terrorist organization surviving on external donations. It is a proto-state with superior fiscal capacity to the legitimate authority it contests.

The revenue asymmetry creates a perverse dynamic. When US assistance flows to Nigerian security forces, it paradoxically validates ISWAP’s claim to superior governance. The insurgents provide dispute resolution, enforce contracts, and collect taxes with greater consistency than the absent Nigerian state. American drones overhead cannot bomb legitimacy into existence.

Geography compounds the problem. Lake Chad’s hydrology generates and erases islands faster than any military can map them. Insurgent sanctuaries regenerate as quickly as they are cleared. The Nigerian military’s kinetic metrics—body counts, cleared villages—measure the wrong variables entirely. Each “successful” operation becomes raw material for grievance narratives transmitted through WhatsApp networks that function like traditional oral rumor systems, only faster.

The insurgency’s roots reach deeper than ideology. When formal pathways to adulthood collapse—education leads nowhere, employment vanishes, marriage becomes unaffordable—armed groups offer more than income. They offer a complete alternative narrative for becoming someone. Boko Haram and bandit networks provide what the Nigerian state cannot: a credible life script. No amount of American firepower addresses this structural vacuum.

The Advisor Trap

American military doctrine distinguishes sharply between advisors and combatants. Advisors train, mentor, and support. They do not fight. This distinction exists on paper.

In practice, advisors systematically violate their non-combat mandates when local forces cannot accomplish critical tasks. This is not mission creep in the traditional sense—a gradual expansion of objectives. It is a predictable structural outcome. Soviet and Cuban advisors in Angola demonstrated the pattern decades ago. When the mission requires capability that partners lack, advisors substitute themselves. The prohibition against direct combat becomes a legal fiction that constrains nothing.

The December airstrikes revealed this dynamic in compressed form. American aircraft conducted strikes that Nigerian forces could not execute with equivalent precision. The operation was framed as support. It was, functionally, combat. The distinction matters for congressional reporting requirements and domestic political optics. It matters less for understanding what American forces actually do.

Current US involvement in Nigeria operates through multiple legal authorities that create their own measurement problems. Operations classified under Section 127e are “operational” when unobserved by Congress but must be reclassified as “support” when reporting triggers observation. The legal status is not fixed—it changes based on who is watching. This architecture incentivizes opacity. What cannot be observed cannot be constrained.

The Trump administration has signaled willingness to expand military action in Africa while simultaneously threatening to withdraw from multilateral frameworks. Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth’s worldview prioritizes “lethality” over legal constraints. Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s instinct favors confrontation with authoritarian competitors. President Trump himself has demonstrated preference for limited strikes that generate political theater over sustained campaigns that require patience. This combination suggests more kinetic action with less strategic coherence.

Why Somalia Is the Wrong Lesson

The Battle of Mogadishu traumatized American military planning for a generation. Eighteen dead soldiers, bodies dragged through streets, a hasty withdrawal—the images created what analysts call “Somalia Syndrome,” an aversion to African intervention that persisted for decades. The lesson seemed clear: avoid urban combat in failed states where local dynamics are poorly understood.

But Nigeria is not a failed state. It has a functioning government, contested elections, and institutional capacity that Somalia lacked in 1993 and still lacks today. The Nigerian military, for all its dysfunction, fields over 200,000 personnel and operates sophisticated equipment including American-supplied A-29 Super Tucano aircraft. The comparison flatters neither country.

The deeper problem with the Somalia analogy is temporal. American military planning operates on rotation cycles of one to two years. Climate projections show 86 million people displaced in Sub-Saharan Africa by 2050—migration flows already locked in by atmospheric physics. The personnel designing intervention strategies will have rotated out long before the consequences of their decisions become visible. They are solving yesterday’s problem with tomorrow’s resources on a timeline that matches neither.

ISWAP explicitly frames the Nigerian state as built on the ruins of the Kanem-Bornu Empire, positioning itself not as insurgency but as restoration of legitimate Islamic governance that existed for eight centuries. This creates a temporal legitimacy claim that American counterterrorism frameworks cannot process. The designation “terrorist” requires fixed organizational identity. But seasonal rainfall patterns and cattle prices create fluid identity shifts—farmer to bandit to insurgent and back—that structurally violate the fixed-identity requirements of US legal frameworks.

The trade routes that Boko Haram uses for logistics began in prehistoric times and reached institutional maturity between the seventh and fifteenth centuries. Modern state borders are twentieth-century constructs attempting to interdict pathways that predate the concept of the nation-state. This is not a problem that additional surveillance can solve.

The Great Power Distortion

American decisions in Nigeria do not occur in strategic isolation. China invested $42 billion in Nigerian energy infrastructure in the first half of 2025 alone, including a $20 billion gas industrial park. Russia’s Africa Corps—the formalized successor to the Wagner Group—operates across the Sahel, offering security partnerships without human rights conditions. France has withdrawn from its former colonial positions, closing its final Chad base in January 2025.

This creates a gravitational shift. As Western military presence collapses across the Sahel, Nigeria’s relative mass in the regional security constellation increases. The sequential expulsion of French and American forces from Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger does not create a vacuum—it creates forced concentration. Nigeria becomes the anchor whether it wants the role or not.

US counterterrorism operations now function as audience cost generators directed at China. By deploying visible, high-tech military assets, Washington signals commitment credibility to Beijing. The actual counterterrorism effectiveness becomes secondary to the demonstration effect. This distorts intervention design toward operations optimized for visibility rather than outcomes.

Nigeria has responded by pursuing arms diversification as strategic autonomy—purchasing from China, Russia, Israel, and the EU simultaneously while investing $1 billion in domestic production capacity. This does not reduce dependency; it creates new bargaining chips that enable more external partnerships by reducing vulnerability to any single patron’s conditionality. Self-sufficiency becomes leverage for deeper entanglement, not independence from it.

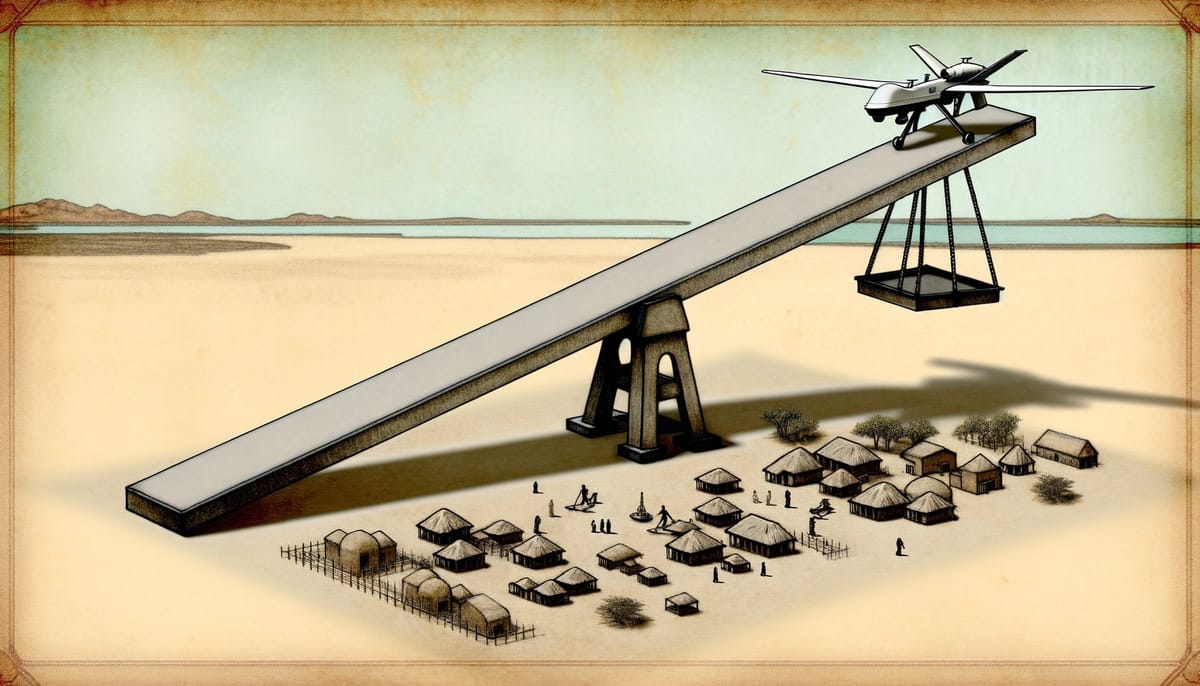

The ISR contractor economy reveals the structural priorities. MQ-9 drone contracts total $219.4 million. Humanitarian aid to the same region over ten years totaled $2.5 million. The ratio—87:1 annually—indicates that AFRICOM’s operational architecture optimizes for sustained surveillance infrastructure sales rather than stability outcomes. A single fiscal year of drone contracts exceeds a decade of humanitarian investment.

What Breaks First

The default trajectory leads toward deeper American involvement with diminishing returns. Each strike generates intelligence requirements for the next strike. Each advisor deployment reveals capability gaps that demand more advisors. The architecture is self-perpetuating.

Nigerian domestic politics will determine the ceiling. The National Assembly operates through patronage networks independent of presidential control, creating legislative veto points that can constrain or enable foreign military presence based on factional calculations rather than strategic logic. Public opinion, shaped by WhatsApp networks that amplify atrocity narratives regardless of their accuracy, can shift rapidly against visible American operations.

The humanitarian situation provides no buffer. At least 7.8 million people will need assistance in 2025. Over two million remain internally displaced. The first half of 2025 saw at least 2,266 killed by bandits or insurgents—a significant escalation from 2024’s approximately 1,400 deaths in Boko Haram and ISWAP violence. The crisis is accelerating, not stabilizing.

Climate-induced migration will compound every existing pressure. The personnel designing current interventions will not be present when their decisions mature. The institutional memory required to learn from mistakes does not exist in rotation-based deployment structures. Each new team rediscovers the same constraints and makes the same errors with fresh confidence.

The Narrow Path

Three intervention points offer leverage, each with significant costs.

First, shift resources from kinetic operations to governance capacity in contested areas. This requires accepting that ISWAP’s fiscal advantage cannot be overcome through military means alone. The Nigerian state must become a more credible provider of services than the insurgency. American assistance could support local government capacity—functional land registries, dispute resolution mechanisms, basic service delivery—rather than additional weapons systems. The cost: reduced visibility, longer timelines, and metrics that do not translate into congressional testimony. The political feasibility is low precisely because success would be invisible.

Second, condition security assistance on human rights compliance with genuine enforcement. The Leahy Law already prohibits assistance to units credibly accused of gross human rights violations, but unit-level vetting treats violations as discrete sins that can be purified through documentation. The violations emerge from institutional culture that vetting cannot address. Meaningful conditionality would require withholding assistance from entire services, not individual units. The cost: reduced Nigerian cooperation and potential pivot toward Russian or Chinese alternatives. The political feasibility is medium—the framework exists, but enforcement requires will that has historically been absent.

Third, invest in regional architecture rather than bilateral relationships. The Multinational Joint Task Force pools sovereignty across Nigeria, Niger, Chad, Cameroon, and Benin. American support for this framework would distribute both burden and legitimacy more broadly than bilateral operations that concentrate risk in a single relationship. The cost: reduced American control over operations and slower decision cycles. The political feasibility is medium-high—the Trump administration’s preference for burden-sharing could align with multilateral frameworks if framed correctly.

The most likely scenario involves none of these. The administration will continue kinetic operations that generate visible results for domestic audiences while avoiding the sustained investment required for structural change. The insurgency will persist. The intervention will expand incrementally. The Somalia comparison will remain inapt but politically useful.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Has the US conducted military strikes in Nigeria before December 2025? A: The December 2025 strikes in Sokoto state were the first known direct US military action inside Nigeria. Previous involvement consisted of training programs, intelligence sharing, and equipment sales through frameworks like the Trans-Sahara Counterterrorism Partnership, which provided over $8 million in support between 2019 and 2023.

Q: How does Boko Haram fund its operations? A: ISWAP, the Islamic State-aligned splinter group, generates approximately $191 million annually through systematic Islamic taxation (darayib), cattle rustling, kidnapping ransoms, and extortion. This revenue exceeds Borno State government income by a factor of ten, enabling the group to provide governance services that compete with the Nigerian state.

Q: What is Somalia Syndrome and why does it matter for Nigeria policy? A: Somalia Syndrome refers to American aversion to African military intervention following the 1993 Battle of Mogadishu, where eighteen US soldiers died. The trauma shaped Pentagon risk calculations for decades. However, Nigeria’s functioning government and different conflict dynamics make the comparison misleading—the real risk is not another Mogadishu but gradual mission expansion without strategic coherence.

Q: How many people are affected by Nigeria’s insurgency? A: The UN estimates 7.8 million people will need humanitarian assistance in Nigeria’s northeast in 2025. Over two million remain internally displaced. At least 2,266 people were killed by bandits or insurgents in the first half of 2025 alone, representing a significant escalation from previous years.

The Long Game Nobody Is Playing

Nigeria risks becoming what it has always feared: a theater where great powers compete while local populations absorb the costs. The insurgency offers one future. American intervention offers another. Neither offers stability.

The Somalia analogy will continue to shape Washington’s caution even as it misleads about the actual risks. The real danger is not a spectacular failure that forces withdrawal. It is a quiet expansion that commits resources without achieving objectives, year after year, rotation after rotation, until the intervention becomes its own justification.

The advisor’s dilemma has no clean resolution. When partners cannot accomplish missions, advisors substitute themselves. When substitution succeeds, it validates the approach. When it fails, it demands escalation. The only exit is strategic clarity about what American military force can and cannot achieve in Nigeria’s northeast—clarity that the current architecture is designed to obscure.

Lake Chad’s islands will continue to appear and disappear with the rains. The insurgency will adapt to whatever pressure is applied. The question is not whether America can win in Nigeria. It is whether America knows what winning would look like, and whether anyone in Washington is willing to say so out loud.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- US Department of State Security Cooperation Fact Sheet - Details of current US-Nigeria military relationship and assistance programs

- Carnegie Endowment: Stabilizing Northeast Nigeria After Boko Haram - Analysis of governance and stabilization challenges

- USIP: Civilian-Led Governance and Security in Nigeria - Research on non-state security governance

- Georgetown Journal of International Affairs: Russia in Africa - Analysis of Russian military proxies in the Sahel

- Global R2P Country Profile: Nigeria - Humanitarian situation and casualty tracking

- African Human Rights Law Journal - Legal frameworks for intervention in Africa

- UN OCHA Nigeria Humanitarian Response Plan 2025 - Current humanitarian needs assessment

- Green Finance & Development Center: China BRI Investment Report - Chinese infrastructure investment in Nigeria