India's hypersonic missile creates mutual vulnerability with China, not strategic advantage

New Delhi's successful test of a Mach 10 anti-ship missile demonstrates technological prowess but enters an arms race India cannot win on industrial terms. The weapon compresses crisis decision-making without shifting the Indian Ocean's fundamental power dynamics.

🎧 Listen to this article

The Mach 10 Mirage

India’s successful test of a hypersonic anti-ship missile in November 2024 sparked predictable headlines about a “game-changer” in the Indian Ocean. Defence analysts proclaimed a new era of naval deterrence. Indian officials spoke of closing the capability gap with China. The missile, traveling at speeds up to Mach 10, would render Chinese surface vessels vulnerable across vast stretches of ocean.

The reality is more complicated—and more interesting.

What India has achieved is technically impressive but strategically ambiguous. The Long-Range Anti-Ship Missile represents a genuine technological leap: a boost-glide system capable of executing terminal maneuvers at hypersonic speeds, evading conventional ship defenses. Yet possession of such a weapon does not automatically translate into altered power balances. China already deploys multiple hypersonic anti-ship systems. India’s entry into this club creates symmetry, not advantage.

The deeper question is whether hypersonic weapons fundamentally change maritime competition—or merely add another layer to an already unstable deterrence relationship. The answer depends less on missile specifications than on geography, industrial capacity, and the psychology of crisis decision-making.

Geography’s Stubborn Arithmetic

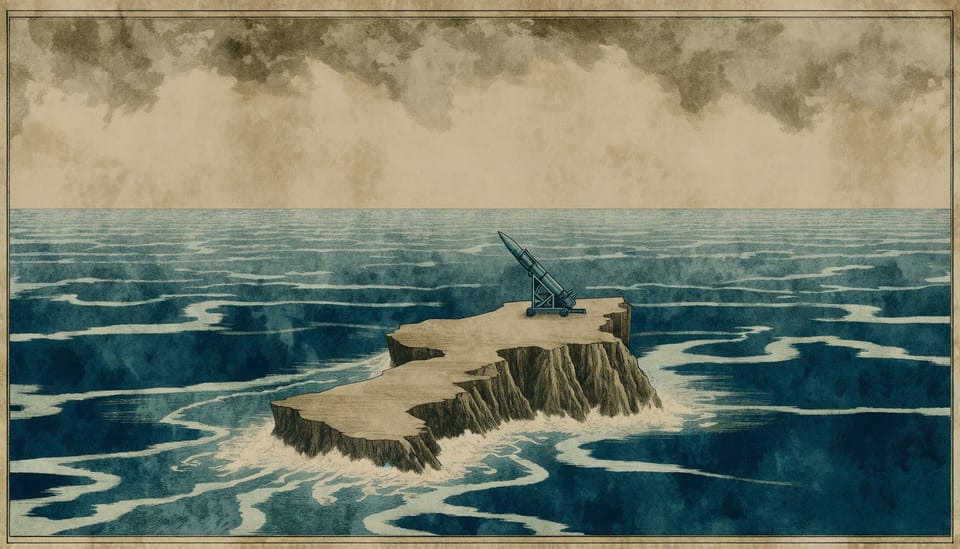

The Indian Ocean is not the South China Sea. This distinction matters more than any missile’s speed.

China’s naval presence in the Indian Ocean operates at the end of extraordinarily long supply lines. The People’s Liberation Army Navy must project power through chokepoints—principally the Strait of Malacca—that India can threaten without firing a shot. Chinese surface vessels operating west of Singapore are, in strategic terms, already vulnerable. India’s geographic position astride these sea lanes provides inherent advantages that no weapon system can replicate for Beijing.

Consider the numbers. India maintains approximately 145 surface combatants and submarines, including two aircraft carriers. The Indian Navy operates from bases spanning the subcontinent’s 7,500-kilometer coastline, plus forward positions in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands—sitting directly athwart Chinese access routes to the Indian Ocean. China’s navy is larger by every metric: over 370 platforms, including major surface combatants and submarines. But size deceives. The bulk of Chinese naval power concentrates in the Western Pacific, where Taiwan and the South China Sea demand attention.

For sustained operations in the Indian Ocean, China depends on a handful of overseas facilities—Djibouti’s small base, port access in Pakistan’s Gwadar, and commercial arrangements elsewhere. These represent footholds, not foundations. India, by contrast, fights in its home waters.

This geographic reality shapes what hypersonic weapons can and cannot accomplish. India’s new missile extends the range at which it can threaten Chinese surface vessels—potentially beyond 1,500 kilometers. But India could already threaten Chinese ships transiting the Malacca Strait using conventional anti-ship missiles, submarines, and land-based aircraft. The hypersonic capability adds speed and penetration probability. It does not create a threat that previously did not exist.

The Speed Paradox

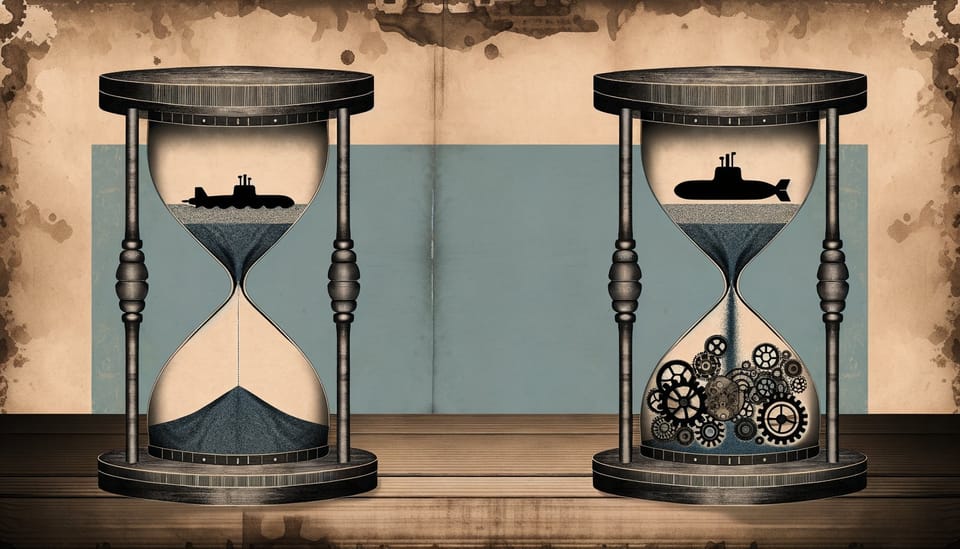

Hypersonic weapons compress time. This is their defining characteristic and their most destabilizing feature.

A conventional anti-ship missile gives defenders minutes to detect, track, and engage. A hypersonic weapon traveling at Mach 8-10 reduces this window to seconds. Ship-based radars cannot see beyond the horizon—roughly 40 kilometers for surface targets. A hypersonic missile appearing over that horizon arrives at its target in under 20 seconds. No existing ship defense system can reliably intercept such a threat.

This creates what strategists call a “use it or lose it” pressure. If your adversary possesses weapons capable of destroying your fleet before you can respond, the incentive to strike first intensifies. Crisis stability analysis has long recognized this dynamic: weapons that favor offense over defense make crises more dangerous.

But here lies the paradox. Both India and China now possess hypersonic anti-ship capabilities. China’s DF-21D and DF-26 anti-ship ballistic missiles have been operational for years. The YJ-21 hypersonic cruise missile entered service more recently. India’s new weapon does not give New Delhi a capability Beijing lacks. It creates mutual vulnerability.

Mutual vulnerability can stabilize—or destabilize—depending on context. During the Cold War, mutual assured destruction between the United States and Soviet Union produced a grim equilibrium. Neither side could strike first without suffering annihilation. But naval warfare operates differently than nuclear deterrence. Ships can be replaced. Losses can be absorbed. The threshold for using anti-ship missiles is far lower than for nuclear weapons.

The result: hypersonic weapons make naval confrontation more dangerous without making it unthinkable. They compress decision timelines during crises while leaving the underlying political disputes unresolved.

What China Actually Worries About

Beijing’s strategic calculus in the Indian Ocean has never centered on defeating the Indian Navy in pitched battle. China’s interests are economic: protecting the sea lanes through which 80% of its oil imports transit. The “Malacca Dilemma”—the vulnerability of Chinese trade to interdiction at this narrow strait—has driven Chinese naval expansion for two decades.

India’s hypersonic missile does not solve this dilemma for New Delhi. It intensifies it for Beijing.

Chinese strategists must now account for the possibility that Indian forces could destroy high-value surface vessels—including any aircraft carrier venturing into the Indian Ocean—before they could be effectively defended. This raises the cost of Chinese naval operations in the region. It does not eliminate China’s ability to operate there.

The more significant effect may be psychological. Research on the reciprocal fear of surprise attack suggests that crisis instability increases when both sides believe the other might strike first. If Chinese commanders perceive Indian hypersonic missiles as a decapitation threat to their Indian Ocean task forces, they face pressure to disperse assets, limit forward deployments, or—in a crisis—strike preemptively against Indian launch platforms.

This dynamic cuts both ways. India must now worry about Chinese preemptive strikes against its hypersonic missile batteries. The weapons designed to enhance deterrence create new vulnerabilities requiring protection. Each side’s attempt to secure advantage generates insecurity for the other.

The Industrial Foundation

Weapons exist only when factories produce them. Here, the asymmetry between India and China is stark.

China’s defense industrial base can manufacture hypersonic weapons at scale. The country produces the specialized materials—tungsten-rhenium alloys, ablative composites—that hypersonic systems require. Chinese production capacity for precision munitions exceeds India’s by an order of magnitude.

India’s situation is different. The successful test demonstrated technological capability. Serial production is another matter. Reports indicate that “further trials and refinements will be required before the missile is ready for production and deployment.” The timeline from successful test to operational deployment typically spans years. During this period, China’s existing hypersonic arsenal grows.

Moreover, every rupee allocated to hypersonic development competes with other naval priorities. India’s submarine fleet ages. Its aircraft carrier program proceeds slowly. Surface combatant construction lags behind stated requirements. The opportunity cost of hypersonic weapons is measured in ships not built and submarines not modernized.

China faces no such trade-offs. Its naval construction program has delivered more tonnage in the past decade than any navy since World War II. Hypersonic weapons represent one component of comprehensive naval modernization, not a substitute for it.

This industrial asymmetry suggests that India cannot win a symmetric arms race with China. The attempt to match Chinese capabilities system-for-system leads to exhaustion, not equilibrium.

The Third Parties

India and China do not compete in isolation. The Indian Ocean hosts multiple actors whose choices shape the regional balance.

The Quad—comprising the United States, Japan, Australia, and India—provides a framework for coordinating responses to Chinese expansion. The Indo-Pacific Maritime Domain Awareness initiative aims to create shared surveillance capabilities across the region. American submarine and surface forces operate regularly in the Indian Ocean. Japanese and Australian naval deployments have increased.

These partnerships offer India something hypersonic missiles cannot: strategic depth through alliance. A Chinese naval task force in the Indian Ocean faces not only Indian forces but the potential intervention of the world’s most capable navy. This changes Beijing’s calculations more than any single weapon system.

Yet alliance dynamics create their own complications. India has historically resisted formal military alliances, preferring “strategic autonomy.” The Quad remains a consultative mechanism, not a mutual defense pact. Whether American forces would intervene in an India-China naval confrontation depends on circumstances no treaty guarantees.

Smaller regional states face acute dilemmas. The Maldives, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh must navigate between Chinese economic inducements and Indian security concerns. Hypersonic weapons do not help these countries; they threaten to make the Indian Ocean more dangerous for everyone. Small island nations increasingly frame hypersonic deployments as existential threats to their climate-stressed societies—another layer of instability the missiles create.

Escalation’s Shadow

The most troubling aspect of hypersonic anti-ship missiles is their ambiguity. A hypersonic weapon in flight looks identical whether it carries a conventional or nuclear warhead. The defender cannot know until impact—if then.

This creates what analysts call “entanglement.” Conventional and nuclear capabilities become intertwined in ways that complicate crisis management. A defender detecting an incoming hypersonic missile must decide whether to treat it as a conventional strike to be absorbed or a nuclear attack requiring retaliation. The compressed decision timeline—seconds, not minutes—makes careful deliberation impossible.

Studies on AI integration with nuclear systems warn that autonomous targeting and launch systems increase the risk of miscalculation. Both India and China are developing AI-enabled command and control capabilities. The combination of hypersonic speed, nuclear ambiguity, and automated decision-making creates pathways to escalation that neither side may intend.

India and China are both nuclear-armed states with histories of border conflict. The 2020 Galwan Valley clash—which killed soldiers on both sides for the first time in 45 years—demonstrated that violence between them remains possible. Hypersonic weapons do not cause such conflicts. But they make managing them more dangerous.

The Verdict

Does India’s hypersonic anti-ship missile shift the Indian Ocean balance of power? Marginally, and not in the direction New Delhi might hope.

The weapon enhances India’s ability to threaten Chinese surface vessels at extended ranges. It complicates Chinese operational planning for Indian Ocean deployments. It demonstrates technological sophistication that may have diplomatic value.

But it does not alter the fundamental asymmetries between India and China. It does not solve India’s industrial limitations or China’s geographic disadvantages. It creates mutual vulnerability without creating stability.

The Indian Ocean balance of power rests on factors that hypersonic weapons cannot change: geography that favors India, industrial capacity that favors China, and alliance relationships that could favor either depending on American choices. India’s missile adds one more variable to this equation. It does not solve it.

What the weapon does accomplish is acceleration—of arms racing, of crisis instability, of the erosion of decision time during confrontations. Both sides now possess the capability to destroy the other’s surface fleet before meaningful defense is possible. This is not deterrence in any stable sense. It is mutual hostage-taking at sea.

The Indian Ocean’s future will not be determined by which side possesses faster missiles. It will be determined by whether either side develops the wisdom to manage competition without stumbling into conflict. On that score, hypersonic weapons offer no assistance whatsoever.

FAQ: Key Questions Answered

Q: How fast is India’s new hypersonic anti-ship missile? A: The Long-Range Anti-Ship Missile can reach speeds between Mach 8 and Mach 10—approximately 6,000 to 7,500 miles per hour. At these velocities, the missile can cover 1,500 kilometers in roughly 12 minutes, giving defenders minimal warning time.

Q: Does China already have hypersonic anti-ship missiles? A: Yes. China has deployed the DF-21D and DF-26 anti-ship ballistic missiles for years, along with the more recent YJ-21 hypersonic cruise missile. India’s new weapon creates parity rather than advantage in this capability class.

Q: Can existing ship defenses stop hypersonic missiles? A: Current naval defense systems cannot reliably intercept hypersonic weapons. The combination of extreme speed and terminal maneuverability defeats most existing interceptor missiles and close-in weapon systems. This is why hypersonic weapons are considered destabilizing.

Q: What does this mean for commercial shipping in the Indian Ocean? A: For peacetime operations, the immediate impact is minimal. The risk emerges during crises, when the presence of hypersonic weapons on both sides creates pressure for preemptive strikes. Commercial shipping through chokepoints like the Strait of Malacca could face disruption if India-China tensions escalate militarily.

The Uncomfortable Equilibrium

India has joined a club it did not need to enter. The hypersonic anti-ship missile represents technical achievement and strategic ambiguity in equal measure. It threatens Chinese vessels without securing Indian waters. It accelerates an arms race India cannot win on industrial terms. It compresses crisis decision-making without providing tools for crisis resolution.

The Indian Ocean will remain contested space. China will continue expanding its presence. India will continue resisting. The missiles flying at Mach 10 change the character of this competition—making it faster, more dangerous, more prone to miscalculation. They do not change its outcome.

What would actually shift the balance? Sustained investment in submarine forces, which operate below the hypersonic threat plane. Deeper integration with Quad partners, which multiplies Indian capabilities without matching Chinese production. Diplomatic engagement with littoral states, which denies China the basing infrastructure it seeks.

None of these alternatives generate headlines about game-changing weapons. All of them would do more to secure India’s position than missiles that arrive too fast for anyone to think clearly about what comes next.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- A Measure for Crisis Instability - Foundational analysis of how weapons characteristics affect crisis stability

- The Reciprocal Fear of Surprise Attack - Classic RAND study on preemption dynamics

- Integration of AI in Nuclear Systems and Escalation Risks - Analysis of AI-enabled command systems

- Controlling the Danger: Managing AI-Enabled Nuclear Systems - CNAS assessment of emerging risks

- Crisis Stability and Nuclear Exchange Risks - NDU analysis of South Asian nuclear dynamics

- Reclaiming Strategic Stability - Carnegie Endowment framework for stability analysis

- AI and ML for the Indian Navy - Assessment of Indian naval modernization priorities