How China could neutralise US bases in Australia without firing a shot

Beijing's strategists have studied the facilities that enable American power projection from Australian soil. Their doctrine suggests disruption, sabotage, and psychological pressure may achieve more than missiles ever could—without triggering the war China wants to avoid.

🎧 Listen to this article

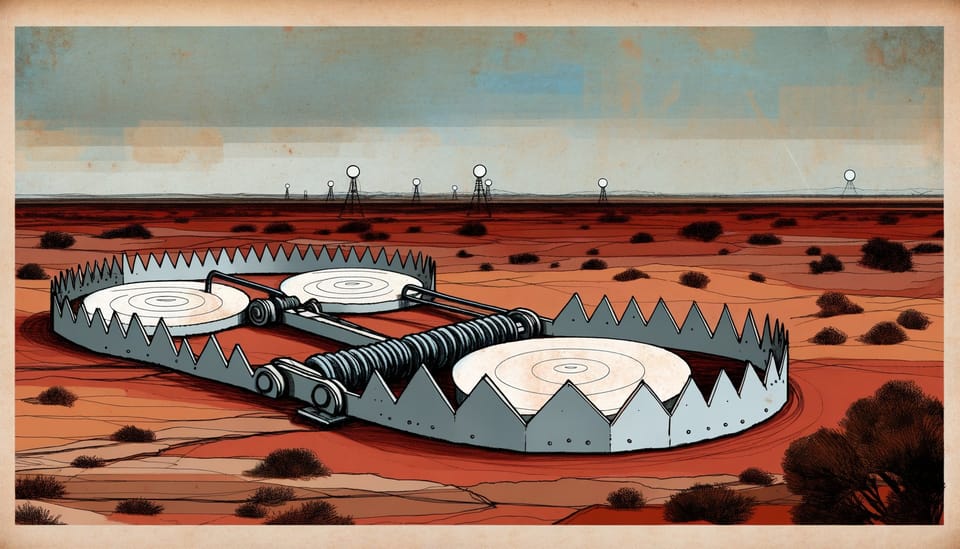

The Shadow Campaign

Pine Gap sits 18 kilometres southwest of Alice Springs, in country the Arrernte people have inhabited for perhaps 40,000 years. Today it hosts one of the most important American intelligence facilities outside the continental United States—a joint signals intelligence station that provides real-time targeting data for US military operations across the Indo-Pacific and beyond. If China sought to blind American power projection in the region without triggering a war that would devastate its own economy and territorial ambitions, this facility and others like it across Australia would present an irresistible logic problem.

The logic runs like this: kinetic strikes on Australian soil would almost certainly invoke ANZUS, drawing America into direct conflict with China. But what if the facilities could be rendered unreliable, their operators uncertain, their host nation politically fractured—all without a single missile being fired? The answer lies in understanding why disruption, sabotage, and psychological coercion may prove more strategically valuable than destruction.

The Invisible Architecture

Australia hosts a constellation of US-linked facilities that collectively form the nervous system of American power projection in the Indo-Pacific. Pine Gap provides signals intelligence and satellite ground control. Naval Communication Station Harold E. Holt near Exmouth handles very low frequency communications to submarines. The Joint Defence Facility at Nurrungar (now largely superseded by Pine Gap’s expanded role) once provided early warning of missile launches. The Jindalee Operational Radar Network (JORN) extends Australia’s surveillance horizon thousands of kilometres into the approaches from the north. American forces rotate through Darwin, Tindal, and other northern bases under the 2014 Force Posture Agreement.

These facilities share three characteristics that shape Chinese targeting logic. First, they are irreplaceable on relevant timescales. According to research by the Nautilus Institute, Pine Gap is “perhaps the most important United States intelligence facility outside that country.” There is no backup. Second, they depend on infrastructure—power grids, telecommunications, supply chains—that was never designed with military resilience in mind. Third, their operation requires Australian political consent that must be continuously renewed.

This last point matters most. The ANZUS Treaty commits parties to “act to meet the common danger in accordance with constitutional processes”—language deliberately vaguer than NATO’s Article 5. Australian governments have historically interpreted this as requiring consultation, not automatic involvement. A China seeking to neutralise these facilities need not destroy them. It need only make their continued operation politically untenable or operationally unreliable.

The Doctrine of Controlled Pressure

Chinese military thinking has evolved a sophisticated framework for achieving strategic objectives below the threshold of armed conflict. PLA colonels Qiao Liang and Wang Xiangsui articulated this in “Unrestricted Warfare”, which outlined how a rising power might challenge a dominant one through non-traditional means: cyberattacks, economic coercion, legal warfare, media manipulation. The goal is not to win a war but to make the war unnecessary by achieving objectives beforehand.

More recently, the PLA has developed what the Jamestown Foundation describes as “Cognitive Domain Operations”—a framework that treats the information environment, public opinion, and decision-maker psychology as legitimate battlespaces. This is not mere propaganda. It represents a systematic effort to shape the conditions under which adversary decisions are made.

Applied to Australia’s US-linked facilities, this doctrine suggests a target logic organised around three objectives: degrading technical capability, eroding political will, and fracturing alliance cohesion. Each objective can be pursued through non-kinetic means that preserve deniability and avoid triggering the escalatory thresholds that would unite Western response.

The technical objective is the most straightforward. Modern military facilities depend on systems of systems—power grids that rely on civilian infrastructure, communications networks that traverse commercial cables, supply chains that source components globally. RAND Corporation research defines gray zone tactics as “coercive activities beyond normal diplomacy and trade but below the use of kinetic military force.” Cyberattacks on supporting infrastructure, supply chain interference, and exploitation of legacy systems all fall within this definition.

The political objective requires understanding Australian domestic dynamics. Pine Gap has long attracted protest from peace activists and Indigenous groups who object to its presence on Arrernte land. ASIO has warned of Chinese state-backed hackers targeting Australian critical infrastructure, but the more sophisticated threat may be influence operations that amplify existing domestic divisions. A population uncertain about whether hosting these facilities serves Australian interests is a population that may demand their closure—or at least impose operational constraints that degrade their utility.

The alliance objective exploits what strategists call the abandonment-entrapment dilemma. Australia fears being abandoned by America in a crisis; it also fears being entrapped in American conflicts that don’t serve Australian interests. Chinese strategy can work both sides of this tension. Demonstrating that America cannot protect Australian infrastructure from non-kinetic attack feeds abandonment fears. Highlighting how Australian facilities make the country a target feeds entrapment concerns. Either dynamic weakens the alliance without requiring China to fire a shot.

The Toolbox of Ambiguity

What specific tools might China employ? The menu is extensive and the categories blur.

Cyber operations offer the most obvious vector. Australia’s Security of Critical Infrastructure Act 2018 now regulates critical infrastructure across eleven key industries, including defence assets. But regulation creates compliance burdens without eliminating vulnerabilities. Legacy SCADA systems controlling power distribution were designed for reliability, not security. Telecommunications networks serving remote facilities like Pine Gap depend on infrastructure that spans thousands of kilometres of sparsely monitored terrain.

The psychological dimension of cyber operations may matter more than the technical. A successful intrusion into systems supporting Pine Gap—even one that extracts no useful intelligence and causes no lasting damage—demonstrates capability. It plants doubt. Operators begin second-guessing their systems. Policymakers begin questioning whether the facilities can be defended. The attack’s success lies not in what it destroys but in what it reveals about vulnerability.

Supply chain sabotage operates on similar principles. Modern defence facilities depend on components sourced globally, maintenance performed by contractors, and logistics chains that span continents. The Chinese-owned Landbridge Group’s lease on the Port of Darwin—secured in 2015 for 99 years—illustrates how commercial relationships create potential pressure points. The national security review of that lease remains secret, but the strategic concern is obvious: a facility’s operational capability depends on infrastructure its adversary may influence.

Hardware trojans represent a particularly insidious threat. Unlike software vulnerabilities that can be patched, malicious modifications to physical components may lie dormant for years before activation. Detection requires inspecting every component in a system—a practical impossibility for complex facilities. The mere possibility of hardware compromise creates uncertainty that degrades operational confidence.

Influence operations complete the toolkit. These need not be crude propaganda. Research on cognitive domain operations suggests the PLA aims to shape “the cognitive foundations of adversary decision-making.” In Australia, this might mean amplifying legitimate concerns about alliance obligations, highlighting costs of hosting US facilities, or exploiting divisions between security elites and broader publics who question whether American interests align with Australian ones.

Why Disruption Beats Destruction

The strategic logic favouring non-kinetic approaches over kinetic strikes is overwhelming.

A missile striking Pine Gap would be an act of war. It would unify Australian public opinion behind the alliance, trigger ANZUS consultations, and likely draw America into direct conflict with China. It would also destroy a facility that took decades to build and cannot be quickly replaced—but at the cost of triggering exactly the war China would prefer to avoid.

Disruption achieves similar operational effects without these costs. A facility whose operators cannot trust their systems, whose power supply is unreliable, whose supply chains are compromised, whose host nation debates whether to maintain it—such a facility is already partially neutralised. Its data becomes suspect. Its operators become cautious. Its political support erodes.

The temporal dynamics matter enormously. Chinese strategic culture, as multiple analysts have observed, operates on longer timescales than Western democracies. Xi Jinping can pursue a twenty-year strategy to degrade alliance cohesion. Australian prime ministers face elections every three years. American presidents every four. This temporal mismatch creates opportunities for patient, cumulative pressure that never crosses thresholds triggering decisive response.

There is also the attribution problem. A cyberattack can be traced to servers in China, but proving state direction is difficult. Supply chain interference may be indistinguishable from commercial decisions. Influence operations exploit legitimate domestic debates. Each action preserves deniability. Each response risks escalation against an adversary that can claim innocence.

The legal ambiguity compounds the strategic advantage. Australia’s legal framework on cybersecurity and international law of armed conflict was designed for a world of clear distinctions between peace and war. Gray zone operations exploit the gap between what is clearly illegal and what triggers military response. A cyberattack that causes no physical damage may violate domestic law but falls short of armed attack under international law. The victim faces the choice of absorbing the blow or escalating against an adversary that has technically done nothing warranting military response.

The Cascade Logic

The most sophisticated Chinese targeting would recognise that facilities exist within systems, and systems have dependencies that create cascade vulnerabilities.

Consider JORN, the over-the-horizon radar network that provides Australia’s primary early warning of air and maritime approaches from the north. Its transmitters and receivers are hardened against direct attack. But they depend on power from grids that serve civilian populations. They depend on communications through networks that handle commercial traffic. They depend on personnel who live in communities that can be influenced.

An adversary seeking to degrade JORN need not attack JORN. It might target the power infrastructure serving the Northern Territory. It might compromise the telecommunications carrying JORN data to analysis centres. It might conduct influence operations in communities hosting JORN personnel, creating social pressure that affects recruitment and retention. Each approach degrades capability without triggering the responses that direct attack would invite.

The same logic applies to Pine Gap’s relationship with American satellite systems, to Harold E. Holt’s role in submarine communications, to the northern bases hosting rotational American forces. Each facility is a node in a network. Each network has dependencies. Each dependency is a potential pressure point.

The Alliance Fracture

Perhaps the most consequential target is not any facility but the alliance itself.

ANZUS rests on assumptions that have never been tested in a Taiwan contingency. Would Australia permit American forces to operate from Australian soil in a conflict China considers defensive? Would Australian publics support involvement in a war over an island most Australians couldn’t locate on a map? Would Australian governments risk economic devastation—China remains Australia’s largest trading partner—for American strategic objectives?

These questions have no clear answers, which is precisely the point. Chinese strategy can exploit the uncertainty. Influence operations can amplify Australian doubts about American reliability. Economic pressure can remind Australians of their vulnerability to Chinese retaliation. Information campaigns can highlight how Australian facilities make Australia a target while providing benefits that flow primarily to Washington.

Japan’s backing of Australia against Chinese economic coercion demonstrates that regional allies recognise the threat. But recognition is not solution. The alliance network in the Indo-Pacific—ANZUS, the Quad, AUKUS—lacks the institutional depth of NATO. Each bilateral relationship has different terms. Each member has different vulnerabilities. Each can be pressured separately.

The Defender’s Dilemma

Australia faces an uncomfortable strategic reality. The facilities that make it valuable to America also make it vulnerable to China. The alliance that provides security guarantees also creates entrapment risks. The geographic distance that once protected Australia now makes it a forward operating location in great power competition.

Defending against the threat requires capabilities that Australia has only begun to develop. Cyber resilience demands investment in systems, training, and redundancy that successive governments have underfunded. Supply chain security requires mapping dependencies that span global networks and reducing vulnerabilities that may be commercially inconvenient. Counter-influence operations require capabilities that democratic societies are uncomfortable wielding.

More fundamentally, defence requires political consensus that the facilities are worth defending. This cannot be assumed. The 2023 Defence Strategic Review acknowledged that Australia faces “the most challenging strategic environment since World War II,” but public debate about what this means for hosting American facilities remains muted. A population that has not considered the costs of alliance may not be willing to bear them when the bill comes due.

What Comes Next

The trajectory is toward increasing pressure with decreasing clarity. China will continue developing gray zone capabilities that test Australian and American responses without triggering them. Australia will continue investing in resilience while hoping the investments prove unnecessary. The alliance will continue providing security guarantees whose credibility cannot be verified until crisis arrives.

The most likely scenario is not dramatic confrontation but gradual degradation. Facilities become less reliable. Operators become less confident. Publics become less supportive. The alliance frays not through rupture but through accumulated doubt. China achieves its objective—neutralising American power projection from Australian soil—without ever crossing the threshold that would unite its adversaries in response.

This is the genius of the gray zone: it makes the defender’s choices harder while making the attacker’s choices easier. Australia can harden facilities, but not the politics that sustain them. It can detect intrusions, but not prove attribution that justifies response. It can maintain alliance commitments, but not eliminate the doubts that erode them.

The question is not whether China will pursue this strategy. The doctrine is clear, the capabilities are developing, the incentives are aligned. The question is whether Australia and its allies will develop responses adequate to a threat designed to evade the responses they have.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Could China actually disable Pine Gap without military attack? A: Not completely, but partial degradation is achievable. Cyber operations could compromise supporting systems, supply chain interference could affect maintenance, and sustained pressure on power infrastructure could force operational limitations. The goal is not destruction but doubt—making the facility’s outputs less trusted and its operation more costly.

Q: Would attacking Australian facilities trigger ANZUS? A: The treaty’s language is deliberately ambiguous. Article IV commits parties to “act to meet the common danger in accordance with constitutional processes”—not automatic military response. Gray zone operations exploit this ambiguity by staying below thresholds that clearly constitute armed attack while still degrading capability.

Q: How vulnerable is Australia’s critical infrastructure to cyberattack? A: Significantly vulnerable. Legacy systems controlling power and water were designed for reliability, not security. The Security of Critical Infrastructure Act 2018 has improved regulation, but compliance varies and determined state actors possess capabilities that exceed most defensive measures.

Q: What is China’s “cognitive domain operations” concept? A: It is a PLA framework that treats information, public opinion, and decision-maker psychology as legitimate domains of warfare. Rather than simply destroying enemy capabilities, cognitive domain operations seek to shape the conditions under which adversaries make decisions—ideally making them choose options that serve Chinese interests.

The Quiet Threshold

In 1984, when Pine Gap’s existence was still officially secret, protesters gathered at its perimeter fence to demand transparency about what the facility did and why Australia hosted it. Four decades later, the facility’s role is publicly acknowledged, its importance to American operations openly discussed, and its vulnerability to non-kinetic attack increasingly apparent.

The protesters were asking the wrong question. The issue was never what Pine Gap does—it collects signals intelligence, supports satellite operations, provides targeting data for American military operations. The issue is what its presence costs, and whether Australians have consented to pay that price.

Gray zone strategy is designed to make that price visible without making the threat clear enough to justify paying it. Each cyber intrusion, each supply chain compromise, each influence operation adds to the ledger. The bill accumulates in degraded confidence, eroded trust, and fractured consensus. When the moment of decision arrives—when Australia must choose whether to permit American operations from Australian soil in a Taiwan contingency—the groundwork will already have been laid for the answer China prefers.

The facilities will still be standing. They may simply no longer matter.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- Nautilus Institute: Pine Gap Introduction - Comprehensive overview of Pine Gap’s role in US intelligence operations

- RAND Corporation: Systems Confrontation and System Destruction Warfare - Analysis of Chinese military doctrine on targeting adversary systems

- Jamestown Foundation: Cognitive Domain Operations - Examination of PLA concepts for influence operations

- CISC: Security of Critical Infrastructure Act 2018 - Australian regulatory framework for critical infrastructure protection

- ABC News: Darwin Port national security review - Reporting on strategic concerns about Chinese infrastructure investment

- ASPI Strategist: Future of US facilities in Northern Australia - Strategic analysis of US force posture in Australia

- Unrestricted Warfare (PDF) - Original PLA text on asymmetric strategy against superior powers

- START: Escalation Management in the Gray Zone - Academic research on gray zone conflict dynamics