Diego Garcia's new landlord: How Mauritius gains leverage over America's most valuable Indian Ocean base

Britain's transfer of Chagos sovereignty to Mauritius preserves US military operations under a 99-year lease—but gives a small island nation with growing Chinese ties quiet leverage that compounds over decades.

The Footprint’s New Landlord

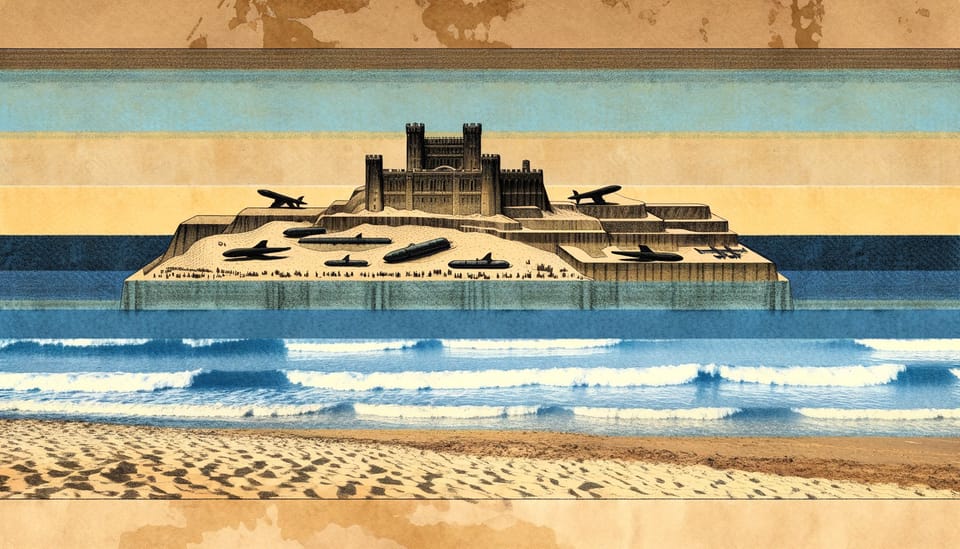

Diego Garcia looks, from the air, like a horseshoe dropped in the Indian Ocean. For fifty years, that horseshoe has been America’s most valuable piece of real estate between the Persian Gulf and the Strait of Malacca. On May 22, 2025, the United Kingdom signed away sovereignty over this atoll to Mauritius—a nation of 1.3 million people that has never operated a military base, but maintains a free trade agreement with China.

The panic in Washington is understandable. Diego Garcia hosts the only runway between Guam and the Gulf capable of launching B-52 bombers. Its deep-water lagoon can shelter aircraft carriers and nuclear submarines. The base has supported every American military operation from Desert Storm to recent strikes against Houthi targets in Yemen. Losing it would punch a 3,000-mile hole in US power projection.

But the panic is also premature. The treaty grants Britain—and by extension America—a 99-year lease with full operational control, extendable for another 40 years. China cannot simply walk in. The real question is subtler: does the change in ownership create leverage that accumulates over time? The answer depends less on what Beijing wants than on what Port Louis needs.

Sovereignty as Financial Derivative

The UK-Mauritius agreement creates something novel in international law: a sovereignty derivative. Mauritius holds the underlying asset. Britain holds operational control. The value of each position depends on the other.

This structure has precedent. Guantánamo Bay operates under a 1903 lease that Cuba has contested for decades without effect. America pays $4,085 annually—a check Havana refuses to cash—and maintains complete control. But the Chagos arrangement differs in one critical respect: it was negotiated, not imposed. Mauritius chose this deal. That choice came with leverage.

The treaty includes provisions for “appropriate financial support” to Mauritius, though precise figures remain undisclosed. British officials describe the package as covering “infrastructure, investment, and resettlement.” Translation: Mauritius extracted a price for legitimizing a base that the International Court of Justice declared illegal in 2019.

That ICJ advisory opinion matters more than its non-binding status suggests. The court ruled 13-1 that Britain’s 1965 separation of the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius was unlawful. The UN General Assembly subsequently demanded British withdrawal by 116 votes to 6. For years, London ignored these rulings. The new treaty represents capitulation dressed as statesmanship.

Why capitulate now? The legal pressure had become operationally awkward. Third countries increasingly questioned whether hosting a base on disputed territory violated international law. The Starmer government, led by a former human rights lawyer who once defended death row inmates pro bono, proved susceptible to arguments about legal legitimacy that his predecessors dismissed.

The result is a 99-year lease that sounds permanent but isn’t. Every lease contains renegotiation points. Every landlord eventually wants more rent.

The Mauritius Variable

China’s relationship with Mauritius operates on multiple frequencies. The most audible is economic. Bilateral trade reached $1.102 billion in 2024. The China-Mauritius Free Trade Agreement, signed in 2019 and effective since 2021, was Beijing’s first with any African nation. Chinese investment flows through Mauritius into the broader African continent, using the island’s tax treaties and financial infrastructure as a gateway.

The less audible frequency is political. Mauritius maintains diplomatic ties with Taiwan—one of only thirteen countries that do—while simultaneously deepening economic integration with Beijing. This balancing act reflects Mauritian pragmatism rather than ideological commitment. Port Louis will deal with whoever offers the best terms.

Prime Minister Navin Ramgoolam embodies this pragmatism. The son of Mauritius’s founding father, he inherited a political machine built on coalition flexibility. His Labour Party has governed in alliance with partners across the ideological spectrum. Ramgoolam’s approach to Diego Garcia follows the same logic: extract maximum value from competing powers without permanently alienating either.

The question is whether China can offer enough to shift Mauritian calculations. Beijing’s playbook in the Indian Ocean relies on infrastructure investment creating dependency. Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port, leased to China for 99 years after Colombo defaulted on loans, provides the template. Pakistan’s Gwadar, Djibouti’s military base, Myanmar’s Kyaukpyu—the “String of Pearls” strategy builds leverage through construction contracts.

Mauritius presents a harder target. The country’s economy depends on tourism, financial services, and textile exports—sectors where Chinese investment offers marginal advantage. Its infrastructure needs are modest compared to larger African nations. Most importantly, Mauritius already has what China typically offers: a functioning port, reliable electricity, and stable governance.

What Mauritius lacks is leverage over a superpower. Diego Garcia provides that.

The Geometry of Access

The base’s military value derives from geography that cannot be replicated. Diego Garcia sits roughly equidistant from the Persian Gulf, the Strait of Malacca, and the East African coast. Its 12,000-foot runway can handle any aircraft in the American inventory. Its lagoon offers protected anchorage for carrier strike groups. Its isolation—1,000 miles from the nearest landmass—provides natural security against surveillance and sabotage.

For US Indo-Pacific strategy, Diego Garcia performs three irreplaceable functions. First, it enables bomber operations that would otherwise require aerial refueling chains stretching across allied territory. B-52s based on Diego Garcia can strike targets from Yemen to the South China Sea without overflight permissions from nervous partners. Second, it supports submarine operations throughout the Indian Ocean, providing maintenance facilities and communications infrastructure that nuclear boats require. Third, it anchors the Satellite Control Network—the ground stations that command American military satellites.

The Pentagon’s distributed operations concept, known as Agile Combat Employment, theoretically reduces dependence on any single base. Aircraft disperse across multiple locations, complicating enemy targeting. But ACE requires a hub from which to disperse. In the Indian Ocean, that hub is Diego Garcia. Lose it, and the spokes have nowhere to connect.

Alternative basing options exist but impose costs. Australia’s Cocos Islands offer proximity but lack infrastructure and face sovereignty sensitivities of their own. Expanding facilities at Djibouti would concentrate assets in a location where China already operates a military base. Singapore and Japan host American forces but are thousands of miles from the Indian Ocean’s western reaches.

The arithmetic is unforgiving. Every alternative adds flight time, reduces payload, and complicates logistics. Diego Garcia’s value lies not in what it can do that others cannot, but in what it can do efficiently that others do expensively.

China’s Indirect Approach

Beijing’s Indian Ocean strategy does not require acquiring Diego Garcia. It requires degrading America’s ability to use it.

The most obvious vector is lease renegotiation. Mauritius cannot evict American forces during the initial 99-year term without violating the treaty. But treaties contain implementation details that require ongoing negotiation. Environmental regulations, labor standards, port access for civilian vessels—each provision offers friction points where Mauritian officials can extract concessions or create delays.

Chinese influence operates through these friction points. A Mauritian government dependent on Chinese investment might interpret environmental provisions strictly, requiring lengthy impact assessments before runway expansions. Officials educated at Chinese universities might staff the agencies overseeing base compliance. Business networks connecting Port Louis to Beijing might lobby for restrictions on military activities that interfere with commercial shipping.

None of this requires Chinese military presence on Diego Garcia. It requires only that Mauritius find Chinese friendship more valuable than American goodwill. Given the disparity in what each power can offer economically, that calculation could shift over decades.

The 68% of Mauritians who trace ancestry to the Indian subcontinent complicate this picture. India views the Indian Ocean as its strategic backyard and maintains close defense ties with Mauritius, including a 2015 agreement to develop facilities on Agalega Island. Every Mauritian bureaucrat with relatives in Gujarat or Tamil Nadu represents a potential counterweight to Chinese influence. India’s “Necklace of Diamonds” strategy explicitly aims to encircle Chinese positions with Indian-aligned facilities.

The result is not a binary choice between American and Chinese alignment but a triangular competition where Mauritius plays each power against the others. This is exactly the game small states play best.

The Chagossian Wildcard

Between 1968 and 1973, Britain forcibly removed the entire population of the Chagos Archipelago to make way for the American base. Approximately 1,500 people were deported to Mauritius and the Seychelles, where many fell into poverty. Their descendants, now numbering around 10,000, have spent five decades demanding the right to return.

The UK-Mauritius treaty addresses this grievance partially. It establishes a “programme for Chagossians to return to the outer islands of the Chagos Archipelago”—but not to Diego Garcia itself, which remains under military control. Resettlement funding forms part of the financial package, though details remain sparse.

This compromise satisfies no one fully. Chagossian activists argue that excluding Diego Garcia perpetuates the original injustice. British parliamentarians question whether the deal adequately protects the community’s interests. American military planners worry that any civilian presence in the archipelago creates security vulnerabilities.

The Chagossian factor constrains all parties’ options. Mauritius cannot appear to abandon the islanders’ cause without domestic political cost. Britain cannot ignore human rights obligations that UN bodies continue to highlight. America cannot dismiss the moral dimension without undermining the “rules-based order” rhetoric that justifies its presence.

For China, Chagossian rights provide a useful rhetorical weapon. Beijing can position itself as supporting decolonization and indigenous rights while Western powers maintain what critics call a “colonial relic.” This framing costs China nothing and complicates Anglo-American messaging throughout the Global South.

The deeper risk is that Chagossian resettlement, once begun, proves difficult to contain. Outer island communities will require supply chains, communications, and administrative presence. Each requirement creates interaction points between civilian and military spheres. Over time, the “sterile” security environment that military planners prefer becomes impossible to maintain.

The Temporal Mismatch

American defense planning operates on four-year cycles tied to presidential elections. Chinese strategy operates on generational timescales. The 99-year lease exists somewhere between these temporal frames—too long for American political attention spans, too short for Chinese patience.

The Trump administration’s return to power in January 2025 accelerated this mismatch. President Trump views international agreements through a transactional lens, questioning arrangements that constrain American freedom of action while providing benefits to partners. His skepticism toward the UK-Mauritius deal—which his predecessor’s administration tacitly supported—reflects broader doubts about whether allies can be trusted to protect American interests.

British domestic politics add another layer of uncertainty. The Diego Garcia agreement requires parliamentary ratification, which Conservative opponents have sought to delay. Parliamentary debates reveal deep divisions over whether the deal adequately protects British strategic interests. A future Conservative government might seek renegotiation, introducing uncertainty that neither Washington nor Port Louis welcomes.

Mauritius faces its own electoral rhythms. Ramgoolam’s coalition depends on delivering economic benefits to constituencies that care little about geopolitics. If Chinese investment offers more visible returns than American lease payments, political incentives shift accordingly. The next Mauritian election could produce a government less accommodating to Western military presence.

These overlapping cycles create what might be called civilizational timescale mismatch. A 99-year lease sounds permanent to politicians serving four-year terms. To strategists thinking in decades, it represents a single renegotiation away from fundamental change.

What Actually Changes

The sovereignty transfer does not give China a base. It does not give China access rights. It does not give China veto power over American operations. What it gives China is time.

Every year that passes, Mauritius accumulates leverage. Infrastructure ages and requires renovation—renovation that needs Mauritian approval. Personnel rotate through the base—personnel who need Mauritian visas. Supplies flow through Mauritian customs. Environmental regulations tighten. Labor standards evolve. Each adjustment offers opportunities for friction.

China need not orchestrate this friction directly. Market forces suffice. As Chinese economic weight in the Indian Ocean grows, Mauritian businesses increasingly orient toward Beijing. As Chinese tourists replace European visitors, Mauritian politicians increasingly court Chinese favor. As Chinese infrastructure projects reshape regional logistics, Mauritian ports increasingly serve Chinese shipping.

The compound effect resembles erosion more than conquest. No single event triggers alarm. No single concession crosses red lines. But over decades, the operational environment degrades. Flight operations face more restrictions. Port calls require more notice. Intelligence activities attract more scrutiny. The base remains, but its utility diminishes.

This is China’s theory of victory in the Indian Ocean: not to seize American positions but to make them progressively less useful. Diego Garcia under Mauritian sovereignty fits this strategy perfectly. The base continues operating, reassuring Washington that nothing fundamental has changed. Meanwhile, the conditions enabling that operation slowly erode.

The Counterplay

American strategists are not oblivious to these dynamics. The response involves three tracks: redundancy, relationship, and reassurance.

Redundancy means reducing dependence on any single facility. The Pentagon’s Pacific Deterrence Initiative funds infrastructure improvements across Guam, Australia, and Japan. Agreements with India expand access to ports and airfields on the subcontinent. New technologies—longer-range aircraft, autonomous systems, space-based logistics—promise to reduce the tyranny of geography that makes Diego Garcia essential.

Relationship means competing for Mauritian alignment. American investment in Mauritius remains modest compared to Chinese flows, but Washington can offer what Beijing cannot: security guarantees, intelligence sharing, and integration into Western financial systems. The challenge is making these offers tangible to Mauritian voters who see Chinese construction projects but not American security umbrellas.

Reassurance means convincing allies that the Diego Garcia arrangement remains stable. Japan, Australia, and India all depend on American power projection capabilities in the Indian Ocean. If these partners doubt American staying power, they may hedge toward accommodation with China. The sovereignty transfer, whatever its legal merits, sends an uncomfortable signal about Western willingness to defend strategic positions.

Each track involves trade-offs. Redundancy costs money that Congress may not appropriate. Relationship-building requires sustained attention that American politics rarely provides. Reassurance demands confidence that the administration may not feel.

The most likely outcome is muddling through. Diego Garcia continues operating much as before. Mauritius collects its payments and maintains studied neutrality. China expands economic influence without dramatic moves. The strategic balance shifts incrementally, noticed only in retrospect.

FAQ: Key Questions Answered

Q: Can China actually build a military base on Diego Garcia? A: Not under the current treaty. The UK-Mauritius agreement grants Britain exclusive operational control for 99 years, with provisions explicitly designed to prevent third-party military access. China would need Mauritius to violate treaty terms—an action that would trigger British and American responses and destroy Mauritian credibility as a treaty partner.

Q: Why did Britain agree to give up sovereignty? A: Legal and political pressure accumulated over years. The 2019 ICJ ruling declared British control illegal. The UN General Assembly demanded withdrawal. The Starmer government, sensitive to international law arguments, concluded that legitimizing the base through negotiated agreement served British interests better than defending an increasingly isolated legal position.

Q: What happens to the Chagossians? A: The treaty permits resettlement on outer islands but not Diego Garcia itself. Funding for resettlement programs forms part of the financial package, though implementation details remain unclear. Chagossian activists continue demanding fuller recognition of their rights, ensuring this issue will resurface in future negotiations.

Q: Could a future US administration withdraw from the arrangement? A: The US is not a direct party to the UK-Mauritius treaty, though American interests shaped its terms. Washington could theoretically refuse to operate under Mauritian sovereignty, but this would mean abandoning a base with no equivalent replacement. The more likely pressure point is demanding treaty modifications that Mauritius may resist.

The Long Game

Sovereignty is a patient weapon. It does not strike; it accumulates. The UK-Mauritius treaty transfers legal title while preserving operational reality. For now, American bombers still launch from Diego Garcia’s runway. American submarines still shelter in its lagoon. American satellites still receive commands from its ground stations.

But legal title matters in ways that compound over time. Every contract requires renegotiation. Every regulation requires compliance. Every incident requires adjudication. In each interaction, the sovereign holds advantages that the tenant lacks. Mauritius may never exercise these advantages dramatically. It may never need to. The mere possibility shapes behavior, constrains options, and creates uncertainty where certainty once existed.

China understands this dynamic better than most. Beijing’s Indian Ocean strategy has never depended on acquiring bases—it depends on making American bases less reliable. A Diego Garcia that operates under Mauritian sovereignty, subject to Mauritian regulations, dependent on Mauritian goodwill, serves this purpose admirably. The base remains American in practice. Its foundation becomes Mauritian in law.

The footprint of freedom now rents from a landlord with options. That changes everything. That changes nothing. Both statements are true, and the tension between them will define Indian Ocean security for the next century.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- UK Government Joint Statement with Mauritius - Primary document announcing the October 2024 political agreement

- UK-Mauritius Treaty Text - The formal agreement signed May 2025

- ICJ Advisory Opinion on Chagos - The 2019 ruling declaring British administration unlawful

- UN General Assembly Resolution 73/295 - The resolution demanding British withdrawal

- Fair Observer Analysis of Chagos Geopolitics - Contextual analysis of displacement and strategic implications

- UK Parliamentary Debates on Diego Garcia - Record of political divisions over ratification

- Oxford Reference on Chagos and Indian Ocean Geopolitics - Academic analysis of the archipelago’s strategic significance

- Satellite Control Network Overview - Technical background on Diego Garcia’s space operations role