China's Antelope Reef signals a strategic shift from deterrence to denial in the South China Sea

Beijing's latest artificial island is not another territorial marker. It is a weapons platform designed to make American operations in the western Pacific prohibitively costly—a shift from threatening retaliation to eliminating options.

🎧 Listen to this article

The Concrete Archipelago

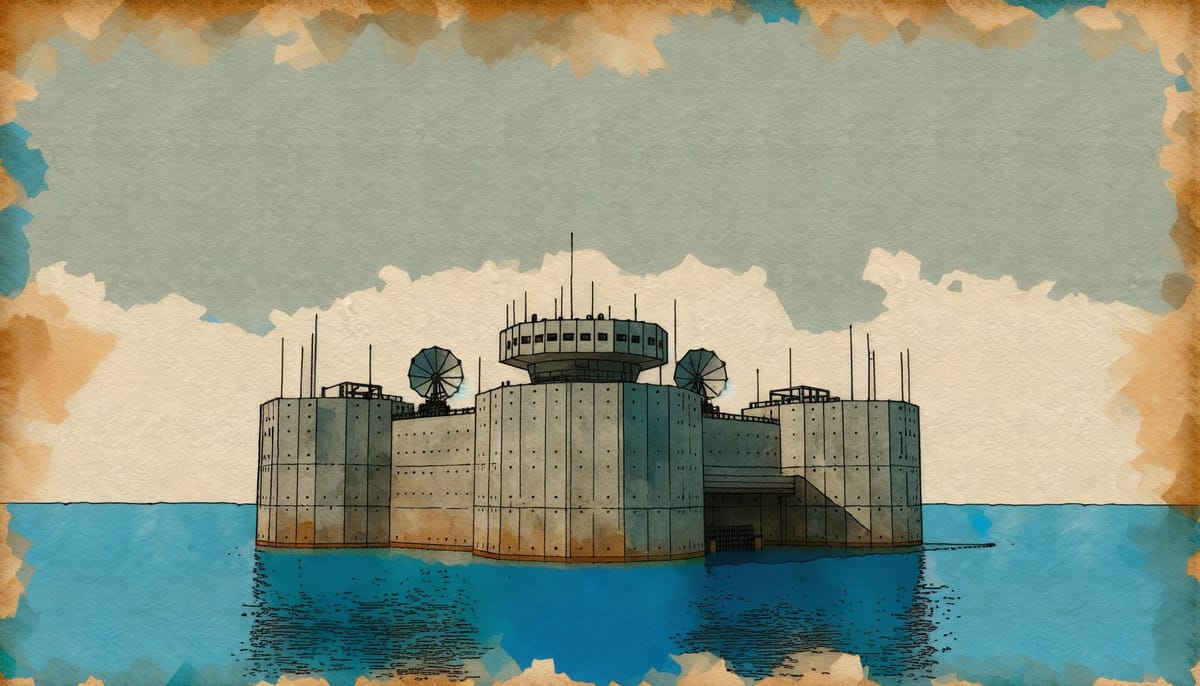

In late 2025, Chinese dredgers arrived at Antelope Reef, a sandbar in the Paracel Islands so unremarkable that even Vietnamese fishermen rarely bothered to anchor there. Within weeks, satellite imagery showed the familiar pattern: sand pumped onto coral, berms rising from the sea, the geometry of runways and helipads taking shape. Beijing had done this before—at Mischief Reef, Subi Reef, Fiery Cross—yet something fundamental had changed. The earlier islands were statements. This one is a sentence.

The distinction matters. For a decade, analysts debated whether China’s artificial islands represented expensive propaganda or genuine military capability. The 2016 arbitration ruling declared them legally meaningless—artificial structures cannot generate territorial seas or exclusive economic zones under international law. Western observers took comfort in this verdict. Beijing, it seemed, was building monuments to a claim the world refused to recognize.

That reading was always incomplete. Antelope Reef reveals its error. China has stopped trying to convince anyone of anything. It is now simply making the South China Sea unusable for adversaries.

From Flags to Fire Control

The shift from deterrence to denial is not semantic. Deterrence operates through psychology: credible threats that change an adversary’s calculations. It requires signaling, communication, the possibility of backing down. Denial operates through physics: capabilities that make certain actions impossible regardless of an adversary’s intentions. One seeks to influence decisions. The other seeks to eliminate options.

China’s early island-building served deterrence logic. The installations on Fiery Cross and Subi Reef—with their airstrips, radars, and ceremonial garrisons—announced presence and resolve. They were expensive ways of saying “we are here, and we will not leave.” The message targeted Washington, Hanoi, Manila, and domestic audiences in equal measure. Success meant adversaries choosing not to challenge Chinese claims because the costs seemed too high.

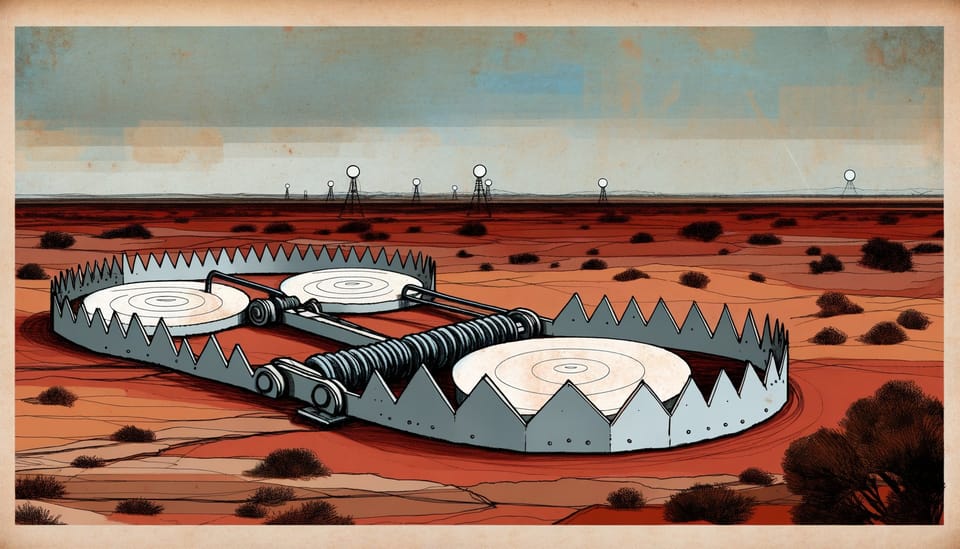

Antelope Reef operates differently. Its location in the Paracels—already under de facto Chinese control since 1974—adds nothing to Beijing’s legal claims. Vietnam and Taiwan dispute ownership, but neither can contest it militarily. The reef’s value lies elsewhere: it plugs a gap in China’s sensor and weapons coverage, creating overlapping fields of fire that transform the northern South China Sea from a space where American and allied forces can operate with risk into a space where they cannot operate at all.

The technical details illuminate the strategic shift. China’s existing installations in the Spratlys—some 1,200 kilometers to the south—can host HQ-9 surface-to-air missiles with ranges of 200 kilometers and YJ-12B anti-ship missiles reaching 400 kilometers. But coverage degrades with distance. Aircraft approaching from the Philippine Sea face detection and engagement from Fiery Cross; those approaching from the north, near Taiwan or Japan, encounter thinner defenses. Antelope Reef, positioned in the Paracels, extends the kill chain northward. Combined with installations on Woody Island, it creates a layered defense that forces adversary aircraft and ships to fly through overlapping engagement zones rather than around them.

This is denial architecture. The goal is not to deter American carrier strike groups from entering the South China Sea—that ship has sailed—but to make their operations inside it so costly that commanders must assume unacceptable losses before achieving objectives.

The Grammar of Grey Concrete

Understanding why this matters requires grasping how denial reshapes conflict. Deterrence preserves options for both sides. It says: “Don’t do this, or we will hurt you.” The threat is conditional. If the adversary complies, nothing happens. If they defy, escalation follows. Both parties retain agency.

Denial removes agency. It says: “You cannot do this, regardless of what you choose.” A ship that cannot survive transit through a weapons engagement zone cannot transit, full stop. The decision has been made by physics, not politics. This is why denial strategies tend toward permanence. Deterrent threats can be withdrawn; concrete cannot.

China’s artificial islands embody this logic in literal form. The 2016 arbitration tribunal ruled that artificial islands “are explicitly denied the legal status of natural islands” and cannot generate maritime zones. Beijing ignored the ruling, but the legal finding contained an unintended insight: because artificial islands have no legal standing, they need not pretend to civilian purposes. They exist purely as military infrastructure. The pretense of fishing shelters and weather stations that accompanied early construction has faded. Antelope Reef is being built as what it is: a weapons platform.

The construction timeline reinforces this interpretation. China’s earlier island-building proceeded in phases—dredging, then infrastructure, then militarization—with pauses that allowed diplomatic management. Antelope Reef is being built rapidly and without the usual theatrical denials. Satellite imagery analyzed by Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative shows simultaneous work on multiple structures, suggesting pre-positioned materials and a construction plan designed for speed rather than ambiguity. Beijing is not waiting to see how the world reacts. It is racing to establish facts before reactions matter.

The Network Effect

A single artificial island is a target. A network of artificial islands is a system. This distinction explains China’s persistence despite the obvious vulnerabilities of fixed installations.

Critics have long noted that artificial islands cannot move, hide, or repair themselves. In a conflict, American long-range strike capabilities could destroy them in hours. This is true but incomplete. The islands’ value lies not in their individual survivability but in their collective effect on operational planning.

Consider the geometry. Before China’s island-building campaign, American forces could approach the South China Sea from multiple vectors with relative freedom. Surface ships could transit the Luzon Strait, aircraft could stage from bases in Japan or Guam, submarines could operate throughout the region with minimal risk of detection. Each Chinese installation narrows these options. Fiery Cross covers the southern approaches. Subi Reef extends coverage eastward. Woody Island dominates the Paracels. Antelope Reef fills the remaining gap.

The result resembles what military planners call an integrated air defense system—overlapping radar coverage feeding centralized fire control, with multiple engagement opportunities for any target. But China’s version extends beyond air defense to include anti-ship missiles, electronic warfare systems, and intelligence collection. The network does not need every node to survive; it needs enough nodes to force adversaries into predictable corridors where concentrated firepower awaits.

This creates a dilemma for American planners. Destroying the islands requires entering the engagement zones they create. Entering the engagement zones means accepting losses. Accepting losses requires political authorization that may not come until the conflict has already been decided. The islands thus achieve denial not through invulnerability but through the decision calculus they impose on adversaries.

Temporal Asymmetries

The shift from deterrence to denial also reflects a temporal calculation. Deterrence requires continuous credibility—the threat must remain believable over time, which demands ongoing investment in signaling and the willingness to escalate if challenged. Denial requires only construction. Once the concrete sets, the capability exists regardless of political will.

This asymmetry favors China in several ways. American defense planning operates on four-year electoral cycles. Administrations change, priorities shift, budgets fluctuate. The Trump administration’s emphasis on great-power competition may give way to different priorities; the Biden administration’s focus on allies may not survive the next election. China’s artificial islands do not care. They will still be there in 2030, 2040, 2050.

The asymmetry extends to alliance management. American strategy in the Indo-Pacific depends on access to bases in Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, and Australia. Each host nation has its own politics, its own vulnerabilities to Chinese economic pressure, its own domestic debates about the wisdom of hosting American forces. China’s denial architecture does not require allied cooperation. It requires only that Beijing maintain control of features it already occupies.

There is a deeper temporal dimension. The “century of humiliation” remains central to Chinese strategic culture—the period from the Opium Wars to the Communist victory in 1949 when foreign powers carved up Chinese territory and imposed unequal treaties. Xi Jinping’s government frames the South China Sea as a space where this humiliation was enacted and where it must now be reversed. The artificial islands are not temporary expedients; they are monuments to permanence. Removing them would require not just military action but the political will to undo what Beijing presents as historical justice.

The Costs of Denial

Denial strategies carry their own vulnerabilities. By foreclosing options, they also foreclose flexibility. China’s artificial islands cannot be moved if strategic circumstances change. They cannot be traded in negotiations because their value is existential rather than instrumental. They cannot be abandoned without catastrophic loss of face.

This creates what economists call a commitment device—a mechanism that binds future behavior by eliminating alternatives. Commitment devices can be powerful: by demonstrating that retreat is impossible, they may convince adversaries not to test resolve. But they also trap their creators. China has invested billions in artificial islands that generate no revenue, serve no civilian purpose, and create ongoing maintenance costs. The sunk cost fallacy applies to nations as well as individuals. Having built the islands, Beijing must defend them.

The environmental costs compound the strategic ones. Dredging destroys coral reefs that took millennia to form. Studies published in Nature document severe damage to marine ecosystems across the Spratlys. The irony is precise: China claims the South China Sea as ancestral waters while systematically destroying the ecosystems that made them valuable. The fish that sustained generations of Chinese, Vietnamese, and Filipino fishermen are disappearing. The reefs that protected coastlines from storms are dying. What remains is concrete and weapons.

Regional Recalculations

China’s shift toward denial forces regional states into uncomfortable choices. Vietnam has responded with its own reclamation activities, expanding outposts in the Spratlys at an accelerating pace. The logic is defensive—if China controls the sea, at least Vietnam can control some islands—but the effect may be counterproductive. By investing in static features, Hanoi locks its response into predictable nodes that fit neatly into China’s surveillance and targeting architecture.

The Philippines faces a different dilemma. Manila won the 2016 arbitration but cannot enforce the ruling. American security guarantees theoretically cover Philippine forces in the South China Sea, but the Mutual Defense Treaty’s application to disputed features remains ambiguous. President Marcos has tilted toward Washington, allowing expanded American base access and conducting joint patrols. Yet Philippine forces remain vastly outmatched. In a crisis, Manila must hope that American intervention arrives before Chinese denial capabilities eliminate the forces it is supposed to protect.

For the United States, Antelope Reef crystallizes a strategic problem that has been building for two decades. The American military retains overwhelming global power projection capability, but that capability depends on access—to bases, to airspace, to sea lanes. China’s denial architecture does not challenge American power globally; it challenges American power specifically in the waters where Beijing’s core interests lie. The asymmetry favors the defender. China need not match American capabilities worldwide; it need only exceed them locally.

The Geometry of Escalation

The most dangerous aspect of denial strategies is their effect on crisis dynamics. Deterrence creates space for signaling, negotiation, and de-escalation. Denial compresses that space. When capabilities rather than intentions determine outcomes, the incentive to strike first increases. If Chinese denial systems can prevent American forces from operating effectively, American planners must consider destroying those systems before a conflict begins. If American planners are considering preemption, Chinese planners must consider striking first to prevent it.

This is the logic of instability that concerned Cold War strategists. Mutual vulnerability created stability because neither side could win by striking first. Denial capabilities threaten to restore the first-strike advantage—not through nuclear weapons but through the ability to neutralize an adversary’s conventional forces before they can be employed.

Antelope Reef alone does not create this dynamic. But Antelope Reef plus Woody Island plus Fiery Cross plus Subi Reef plus the submarines and aircraft and missiles that operate from them—this network approaches the threshold where American commanders must assume significant losses in any South China Sea operation. Once that assumption takes hold, the temptation to escalate early or avoid engagement entirely becomes overwhelming.

What Comes Next

The trajectory is clear. China will complete Antelope Reef and integrate it into its existing network. Additional features may follow—the Paracels contain other reefs suitable for development. Each addition extends coverage, increases redundancy, and raises the costs of American intervention.

Regional states will continue hedging. Vietnam will build more outposts while maintaining economic ties with Beijing. The Philippines will deepen security cooperation with Washington while avoiding actions that might trigger Chinese retaliation. Australia, Japan, and South Korea will invest in their own denial capabilities—longer-range missiles, more submarines, better surveillance—while hoping they never need to use them.

The United States faces a choice it has avoided for years: accept that the South China Sea is becoming a Chinese lake, or invest in the capabilities needed to contest that outcome. The first option means abandoning allies and conceding regional hegemony. The second option means spending hundreds of billions on weapons designed for a war that might never come—and might prove catastrophic if it does.

Neither option is attractive. Both are available. What is no longer available is the comfortable assumption that American power can be projected into the western Pacific without serious opposition. Antelope Reef, that former sandbar now rising from the sea in steel and concrete, has foreclosed that possibility.

The question is not whether China has shifted from deterrence to denial. The dredgers have answered that. The question is what the United States and its allies will do about it—and whether they will decide before the concrete sets.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Why can’t artificial islands generate territorial waters under international law? A: UNCLOS Article 60(8) explicitly denies artificial islands the legal status of natural islands. They cannot generate territorial seas, exclusive economic zones, or continental shelf claims—only a 500-meter safety zone. The 2016 arbitration tribunal confirmed this applies to China’s South China Sea constructions.

Q: How many artificial islands has China built in the South China Sea? A: China has constructed or significantly expanded seven features in the Spratly Islands (Fiery Cross, Subi, Mischief, Johnson South, Cuarteron, Gaven, and Hughes Reefs) plus installations in the Paracels including Woody Island and now Antelope Reef. Together these host over 3,000 acres of artificial land.

Q: What weapons has China deployed to its artificial islands? A: Confirmed deployments include HQ-9 surface-to-air missile systems (200km range), YJ-12B anti-ship cruise missiles (400km range), radar installations, and military-grade runways capable of hosting fighter aircraft. The 2024 Pentagon report documents continued expansion of these capabilities.

Q: Could the US military destroy China’s artificial islands? A: Technically, yes—American long-range strike capabilities could damage or destroy fixed installations. Practically, doing so would require entering Chinese weapons engagement zones, accepting significant losses, and triggering a conflict with unpredictable escalation dynamics. The islands’ value lies partly in the political costs they impose on such decisions.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative - Satellite imagery analysis and tracking of South China Sea developments

- Nature: Evidence of Environmental Changes - Scientific documentation of ecological damage from island construction

- MARSAFE Law Journal - Legal analysis of artificial island status under UNCLOS

- RAND Corporation - Scenario analysis for protracted conflict with China

- South China Sea Probing Initiative - Tracking of Vietnam’s reclamation activities

- Pacific Forum - Analysis of undersea infrastructure threats

- Paradigm Shift - Historical context on Chinese strategic culture

- Military Strategy Magazine - Assessment of distributed maritime operations