Can America strike Iran without Gulf bases? The uncomfortable arithmetic of Middle East deterrence

When B-2 bombers hit Iranian nuclear facilities in January 2025, they flew from Missouri—not Qatar or the UAE. Gulf allies are hedging, and Washington's regional leverage is narrower than it admits.

🎧 Listen to this article

The Geography of Constraint

In January 2025, when the United States launched Operation Midnight Hammer against Iran’s nuclear facilities at Fordow, Natanz, and Isfahan, the B-2 bombers flew from Missouri. Not from Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar. Not from Al Dhafra in the UAE. From Whiteman Air Force Base, 11,000 kilometers away, requiring multiple aerial refueling cycles over international waters.

The strikes worked. The IAEA confirmed extensive damage to underground tunnels and enrichment facilities. But the operation revealed something Washington prefers not to discuss: America’s Gulf allies had quietly made themselves unavailable.

This was not a surprise. For years, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Qatar, and Bahrain have been hedging—maintaining American bases while signaling to Tehran that those bases will not become launchpads for regime-threatening attacks. The result is a peculiar arrangement. Some 40,000 to 50,000 US troops occupy at least 19 sites across the Gulf. Eight permanent bases span the region. Yet when Washington needed to strike Iran, it operated as if those bases existed on a different planet.

The question now consuming defense planners is whether this arrangement can sustain American deterrence—or whether the United States has purchased an expensive fiction.

The Dependency Inversion

The conventional understanding runs like this: Gulf states need American protection against Iranian aggression, so they host American forces. In exchange for this protection, they provide basing access for regional operations. Both sides benefit. Both sides understand the arrangement.

This understanding is incomplete.

The relationship has inverted. American military spending created what analysts call a “dependency pathway” in Gulf economies—not dependency of the Gulf on American protection, but dependency of American force projection on Gulf acquiescence. The United States cannot easily relocate its Central Command forward headquarters from Qatar. It cannot quickly replicate the Fifth Fleet’s infrastructure in Bahrain. It cannot reproduce the logistics networks built over three decades of continuous presence.

Gulf monarchies understand this leverage. They also understand that Iran has 150,000 missiles and rockets capable of devastating their cities. Saudi Arabia’s oil infrastructure at Abqaiq and Khurais was struck by Iranian-backed drones in 2019. The UAE’s capital was hit in 2022. Both countries absorbed the lesson: American protection is valuable, but not if it transforms them into primary targets for Iranian retaliation.

The result is strategic hedging of remarkable sophistication. According to analysis from the Middle East Institute, Gulf states have learned to “keep the US close while hedging against it”—maintaining security partnerships while developing parallel relationships with Beijing and pursuing direct diplomatic channels to Tehran. China brokered the Saudi-Iranian rapprochement in March 2023. That agreement did not end the Saudi-American relationship. It gave Riyadh options.

For American planners, the implications are stark. Gulf bases provide peacetime presence, training capacity, and crisis-response infrastructure. They do not provide assured access for offensive operations against Iran. The distinction matters.

What Remains When Bases Disappear

Military operations against Iran without Gulf basing remain feasible. They become more expensive, more complex, and more dependent on capabilities that exist in limited quantities.

Start with the bomber force. B-2 Spirit aircraft can reach any target on Earth from continental American bases, given sufficient tanker support. The January 2025 strikes demonstrated this capability. Diego Garcia, the British-controlled atoll in the Indian Ocean, provides a forward staging point that reduces refueling requirements. B-2s operating from Diego Garcia can strike Iranian targets with fewer tanker cycles than missions from Missouri.

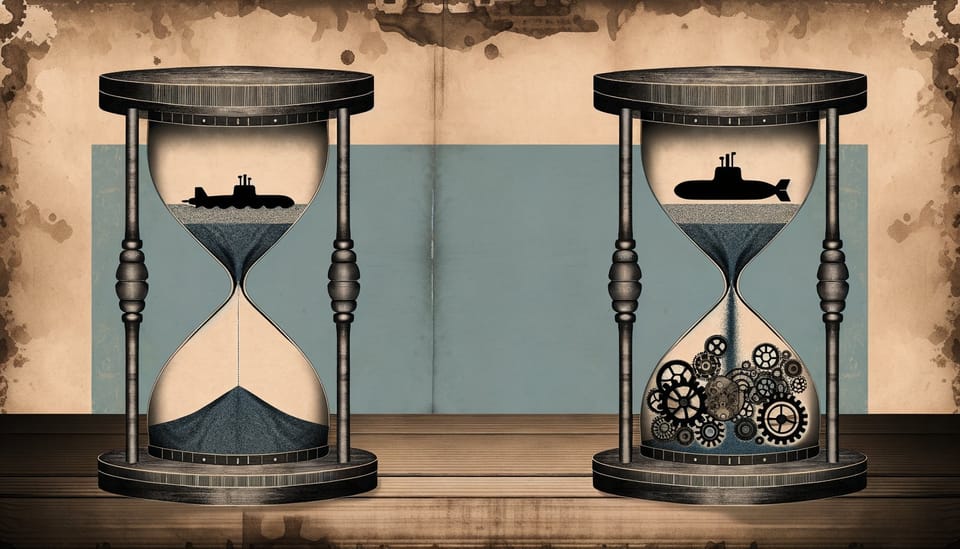

But the B-2 fleet numbers 20 aircraft. The B-21 Raider, its successor, is entering service slowly. These are strategic assets with global commitments. Dedicating them to sustained Iran operations means accepting risk elsewhere.

Carrier strike groups offer another option. The Arabian Sea provides international waters from which aircraft can reach Iranian targets without requiring overflight permissions from Gulf states. A carrier air wing can generate significant strike capacity—RAND analysis suggests that electromagnetic launch systems can increase sortie rates by 33% over legacy catapults. But carriers operate within range of Iranian anti-ship missiles. The Strait of Hormuz, through which carriers must transit to reach optimal launch positions, presents a chokepoint Iran has spent decades preparing to contest.

Submarine-launched cruise missiles provide a third pathway. Tomahawk missiles can be fired from positions Iran cannot easily target. Yet submarines carry limited magazines. A Virginia-class submarine holds perhaps 40 Tomahawks. Destroying hardened nuclear facilities requires sustained bombardment, not single salvos. The Massive Ordnance Penetrator—the 30,000-pound bunker-buster designed specifically for facilities like Fordow—cannot be delivered from submarines. Only B-2s and B-52s can carry it.

The arithmetic becomes uncomfortable. Without Gulf basing, the United States can execute strikes. It cannot sustain campaigns.

The Credibility Equation

Deterrence depends on adversary belief. Iran must believe that American threats carry consequences. This belief rests on demonstrated capability, demonstrated will, and demonstrated access.

The January 2025 strikes established capability. American precision weapons can penetrate Iranian defenses and destroy hardened facilities. That message was received.

Will remains contested. Congressional Research Service analysis notes that Iran “suffered repeated defeats across the Middle East since the beginning of 2024,” including damage to regional proxies and “underwhelming performance” of its ballistic missile program. Yet these defeats have not produced Iranian capitulation. They may be pushing Tehran toward nuclear weapons as the ultimate guarantor of regime survival.

Access is where deterrence frays. Gulf states’ hedging signals to Iran that American operations face political constraints beyond Washington’s control. Every diplomatic visit by Gulf leaders to Tehran, every Chinese-brokered agreement, every public statement emphasizing regional stability over confrontation—these communicate that American bases exist on sufferance.

The effect resembles what deterrence theorists call “extended deterrence” failure. The United States can protect itself. Whether it can protect allies—or use allied territory to project power—becomes uncertain. Heritage Foundation analysis of the Abraham Accords suggests these normalization agreements have created new cooperation channels, but also new constraints. Gulf states with economic ties to Israel have additional reasons to avoid becoming staging grounds for regional wars.

Iran’s calculus adjusts accordingly. If American strikes require 36-hour bomber missions from Missouri, Tehran gains warning time. If carrier operations in the Arabian Sea face anti-ship missile threats, Tehran gains escalation leverage. If every American military option carries political costs with Gulf allies, Tehran gains negotiating space.

Deterrence has not collapsed. It has become conditional.

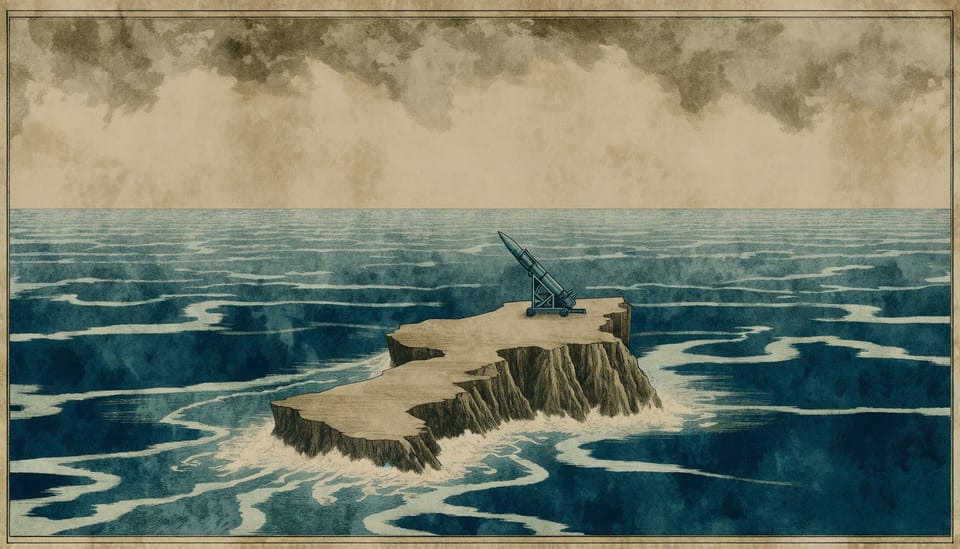

The Diego Garcia Question

One facility deserves particular attention. Diego Garcia, the horseshoe-shaped atoll 1,600 kilometers south of India, hosts the most important American base that most Americans have never heard of.

The base exists because of a legal arrangement that may not survive the decade. Britain leased Diego Garcia to the United States in 1966, after forcibly removing the indigenous Chagossian population. In 2019, the International Court of Justice ruled that British sovereignty over the Chagos Archipelago was illegal. In 2024, Britain announced negotiations to transfer sovereignty to Mauritius.

The United States has sought guarantees that any sovereignty transfer will preserve base access. But the precedent matters. Diego Garcia demonstrates that American power projection depends on arrangements with third parties—arrangements that can be contested, renegotiated, or withdrawn.

For Iran operations, Diego Garcia provides irreplaceable value. B-2 bombers stationed there can reach Iranian targets with significantly less tanker support than CONUS-based missions. The base sits beyond Iranian missile range. Its isolation provides operational security that Gulf bases cannot match.

Lose Diego Garcia, and the geometry of Iran strikes changes fundamentally. The United States would depend entirely on carrier operations and ultra-long-range bomber missions. Both options work. Neither provides the sustained capacity that deterrence requires.

The Iranian Response

Tehran has not passively observed these dynamics. Iranian strategy has evolved to exploit precisely the constraints that Gulf hedging creates.

Iran’s proxy networks operate on what analysts describe as rhizomatic principles—decentralized, redundant, capable of regenerating after losses. The Houthis in Yemen, Hezbollah in Lebanon, militias in Iraq and Syria—these forces can threaten Gulf infrastructure regardless of where American bombers launch from. The September 2019 Abqaiq attack demonstrated that Iranian-aligned forces can strike Saudi oil facilities with precision. The message to Riyadh was clear: hosting American strikes means accepting Iranian retaliation through channels Washington cannot easily interdict.

Iran’s missile forces have multiplied. Estimates suggest over 3,000 ballistic missiles of various ranges, plus thousands of shorter-range rockets and drones. These weapons cannot prevent American strikes. They can impose costs on any Gulf state that enables them.

Most significantly, Iran has developed what might be called “strategic patience.” The Islamic Republic operates on timescales that American political cycles cannot match. Supreme Leader Khamenei has survived since 1989. The Revolutionary Guards’ senior leadership thinks in decades. They can wait for American attention to shift, for Gulf hedging to deepen, for the costs of confrontation to accumulate.

The January 2025 strikes set back Iran’s nuclear program. They did not end it. IAEA reporting confirms that enrichment activities had not restarted as of early 2026—but the knowledge base remains intact, the scientific personnel survived, and the political motivation for nuclear weapons may have strengthened.

The Structural Bind

American strategists face a problem without clean solutions.

Option one: Accept Gulf constraints and optimize for limited operations. This means investing in long-range strike capabilities, expanding Diego Garcia infrastructure, developing new basing arrangements in less constrained locations. The approach is expensive and time-consuming. It concedes that American power projection in the Gulf depends on platforms that exist in small numbers and require years to produce.

Option two: Pressure Gulf allies to provide assured access. This risks the relationships themselves. Saudi Arabia and the UAE have alternatives. Chinese arms sales are expanding. Russian diplomatic engagement continues despite Ukraine. If Washington demands unconditional basing access, Gulf capitals may calculate that diversification serves their interests better than dependence.

Option three: Reduce commitments and accept diminished deterrence. This is the path of least resistance and greatest risk. If Iran concludes that American threats are hollow, nuclear breakout becomes more attractive. If Gulf allies conclude that American protection is unreliable, their hedging accelerates. The equilibrium unravels.

The most likely trajectory combines elements of all three. Washington will invest in standoff capabilities while maintaining the fiction of Gulf cooperation. Gulf states will host American forces while quietly constraining their use. Iran will probe the boundaries of acceptable behavior, advancing its nuclear program incrementally while avoiding the bright lines that might trigger American action despite political costs.

This is not deterrence collapse. It is deterrence decay—a gradual erosion of credibility that no single decision causes and no single decision can reverse.

The Deeper Pattern

The Gulf basing dilemma reflects something larger than regional politics. American power projection has always depended on forward presence—bases in allied territory that transform theoretical capabilities into operational realities. This model assumed that allies would remain allies, that access would remain assured, that the costs of hosting American forces would remain acceptable.

These assumptions are weakening everywhere. Not just in the Gulf. The Philippines renegotiated base access in 2023. South Korea faces domestic pressure over American troop presence. Even Japan, the anchor of American Pacific strategy, debates the terms of alliance.

The pattern is not anti-Americanism. It is multipolarity. States with options exercise them. States that once depended entirely on American protection now cultivate alternatives. The unipolar moment, when American preferences faced no serious competition, has passed.

For military planners, this means rethinking the relationship between capability and access. Hypersonic weapons, autonomous systems, and space-based assets may eventually reduce dependence on forward bases. But “eventually” spans decades. The technologies are immature. The industrial base to produce them at scale does not exist. The doctrines for employing them remain theoretical.

In the meantime, deterrence rests on what can be done with what exists. And what exists requires access that allies may not provide.

What Comes Next

The honest answer is uncomfortable. American deterrence against Iran is not hollow—but it is thinner than Washington acknowledges.

The United States can execute devastating strikes against Iranian targets without Gulf basing. It demonstrated this capability in January 2025. But strikes are not campaigns. Campaigns require sustained operations. Sustained operations require infrastructure that Gulf allies control.

This does not mean Iran can act with impunity. The January strikes imposed real costs. Iranian nuclear facilities will take years to rebuild. The regime understands that American patience has limits.

But limits cut both ways. Iran knows that every American military option carries political costs—with Gulf allies, with European partners, with domestic audiences weary of Middle Eastern entanglements. Tehran can calibrate its provocations to stay below thresholds that would justify those costs.

The result is a new equilibrium, less stable than the old one. American deterrence remains credible for catastrophic scenarios—an Iranian nuclear test, a direct attack on American forces, an attempt to close the Strait of Hormuz. It becomes less credible for incremental provocations—gradual enrichment advances, proxy attacks on Gulf infrastructure, regional destabilization that stops short of bright lines.

Gulf allies will continue hedging. They have no incentive to stop. American protection remains valuable; American wars do not. The rational strategy is to maintain the relationship while constraining its most dangerous implications.

Iran will continue probing. The regime has survived sanctions, strikes, and isolation. It will not abandon its nuclear ambitions because of a single operation, however successful. The question is whether it concludes that the final step—actual weapons—is worth the risk.

The answer depends on whether American deterrence remains credible enough to make that calculation negative. Right now, the margin is narrower than it should be.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Can the US military strike Iran without using bases in Saudi Arabia, UAE, or Qatar? A: Yes. The January 2025 strikes on Iranian nuclear facilities used B-2 bombers flying from Missouri with aerial refueling over international waters. Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean provides a closer staging point. Carrier strike groups can operate from the Arabian Sea. These options work for limited strikes but cannot sustain prolonged campaigns.

Q: Why are Gulf states reluctant to allow US strikes on Iran from their territory? A: Gulf monarchies fear Iranian retaliation. Iran possesses over 3,000 ballistic missiles capable of reaching Gulf cities and critical infrastructure like oil facilities. The 2019 attack on Saudi Arabia’s Abqaiq facility demonstrated this vulnerability. Gulf states prefer to maintain security ties with Washington while avoiding actions that would make them primary targets.

Q: What would happen to US military operations if Diego Garcia became unavailable? A: Losing Diego Garcia would significantly complicate Iran operations. B-2 bombers would need to fly from continental US bases, requiring more aerial refueling and longer mission times. The US would depend more heavily on carrier operations within range of Iranian anti-ship missiles. No other facility in the region offers comparable security and capability.

Q: Is US deterrence against Iran still effective? A: Deterrence remains credible for major provocations—nuclear weapons development, direct attacks on American forces, attempts to close the Strait of Hormuz. It is less effective against incremental advances and proxy operations that stay below escalation thresholds. The gap between American capability and assured access creates uncertainty that Iran can exploit.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- Congressional Research Service: “Iran: Background and U.S. Policy” - Comprehensive assessment of Iranian military capabilities and US policy options

- RAND Corporation: “Future Aircraft Carrier Options” - Technical analysis of carrier strike capabilities and sortie generation

- Heritage Foundation: “The Abraham Accords Five Year Report” - Assessment of normalization agreements and regional security implications

- Middle East Institute: “The Abraham Accords” - Analysis of Gulf state diplomatic strategies and hedging behavior

- IAEA: “Update on Developments in Iran” - Official reporting on Iranian nuclear facility status post-strikes

- Army University Press: “The Role of Forward Presence in U.S. Military Strategy” - Doctrinal analysis of forward basing requirements

- Emirates Diplomatic Academy: “Abraham Accords: Legal Interpretation” - Legal framework governing Gulf state security arrangements