Britain cedes Diego Garcia sovereignty—but America keeps the base

The UK-Mauritius agreement transfers sovereignty over the Chagos Archipelago while preserving a 99-year US military lease. Critics warn of strategic disaster. The operational reality is far more mundane—and the legal foundations far stronger.

🎧 Listen to this article

The Footprint That Won’t Fade

On October 3, 2024, the British government announced it would cede sovereignty over the Chagos Archipelago to Mauritius. Within hours, American commentators declared this the beginning of the end for US power projection in the Indian Ocean. Senator Marco Rubio called the deal “a serious strategic mistake.” Heritage Foundation analysts warned of a Chinese foothold emerging in waters Washington had dominated for half a century. The rhetoric suggested Diego Garcia—the remote atoll hosting America’s only military base in the Indian Ocean—was about to slip from Western control.

The hysteria was misplaced. Under the UK-Mauritius agreement, Britain retains a 99-year lease on Diego Garcia, with options for renewal. The base will continue operating “well into the next century.” American bombers will still take off from its 12,000-foot runway. American submarines will still resupply in its lagoon. The sovereignty transfer changes the flag flying over administrative buildings. It does not change the strategic geography of the Indian Ocean.

Yet the panic reveals something important: a profound misunderstanding of how American military power actually works in the twenty-first century, and what China containment requires. Diego Garcia matters. But not in the way its loudest defenders claim.

What Diego Garcia Actually Does

The base earns its nickname—“the Footprint of Freedom”—through geography rather than firepower. Positioned roughly 1,000 miles from the nearest landmass, Diego Garcia sits at the crossroads of three continents. From its runway, B-52 bombers can reach the Persian Gulf, the Horn of Africa, and the South China Sea. Its lagoon can shelter an entire carrier strike group. Its pre-positioned ships carry enough equipment to sustain a Marine brigade for thirty days without resupply.

This makes Diego Garcia what military planners call a “lily pad”—a logistics hub enabling power projection across vast distances. During Operation Desert Storm, B-52s flew from Diego Garcia to strike Iraqi positions. During the Afghanistan campaign, the base served as a critical refueling point for bombers conducting missions over Central Asia. More recently, it has supported operations against Houthi forces in Yemen.

The base’s value lies in its remoteness. Unlike facilities in the Middle East or Southeast Asia, Diego Garcia faces no host-nation political constraints. No local population protests American operations. No allied government demands consultation before strikes. The atoll offers what strategists call “strategic depth”—distance from potential adversaries combined with freedom of action.

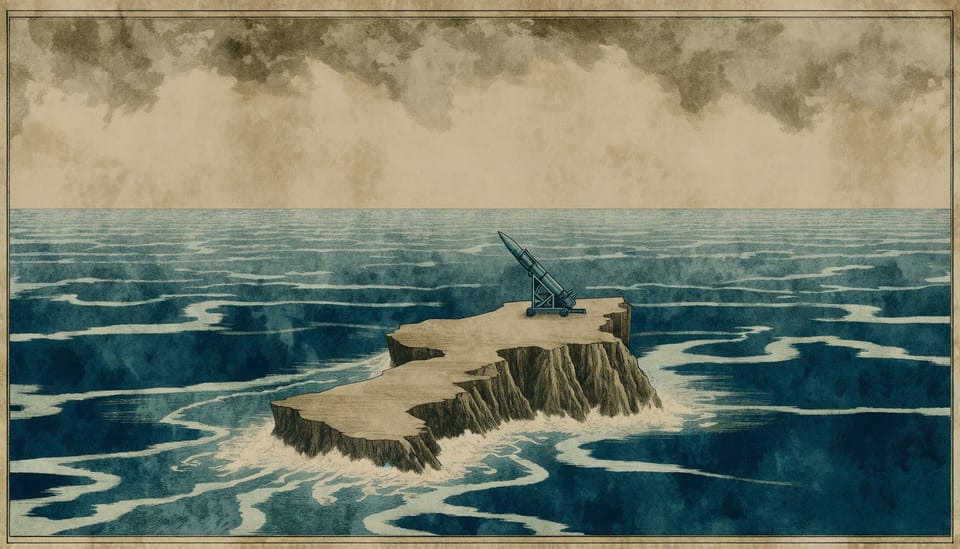

But this same remoteness creates vulnerabilities. Diego Garcia is, as Chatham House noted, “one of two critical U.S. bomber bases in the Indo-Pacific region, alongside Andersen Air Force Base in Guam.” Two bases. For an ocean spanning 28 million square miles. This is not a network. It is a pair of isolated outposts separated by 4,500 miles of water.

The Containment That Isn’t

The question of whether Diego Garcia is “critical for China containment” assumes a strategy that does not exist in the form its proponents imagine. American planners do not speak of containing China the way Cold War strategists spoke of containing the Soviet Union. The 2022 Indo-Pacific Strategy emphasizes “decentralized force posture” and “expanded partnerships”—language that deliberately moves away from the fortress-basing model Diego Garcia represents.

There are good reasons for this shift. China’s military modernization has made fixed bases increasingly vulnerable. The DF-26 intermediate-range ballistic missile—nicknamed the “Guam Killer”—can strike targets 4,000 kilometers away with precision guidance. Diego Garcia lies within range of similar systems deployed from Chinese positions in the South China Sea or, potentially, from facilities China might access through its network of commercial port investments across the Indian Ocean.

The US military has responded by developing concepts like Agile Combat Employment, which disperses aircraft across multiple austere locations rather than concentrating them at major bases. The logic is simple: a single missile strike on Diego Garcia could destroy dozens of aircraft and years of accumulated logistics. The same missiles spread across twenty locations would need to find and hit twenty separate targets.

This does not make Diego Garcia irrelevant. It makes the base one node in a network rather than the network’s irreplaceable center. The distinction matters enormously for assessing what sovereignty transfer actually threatens.

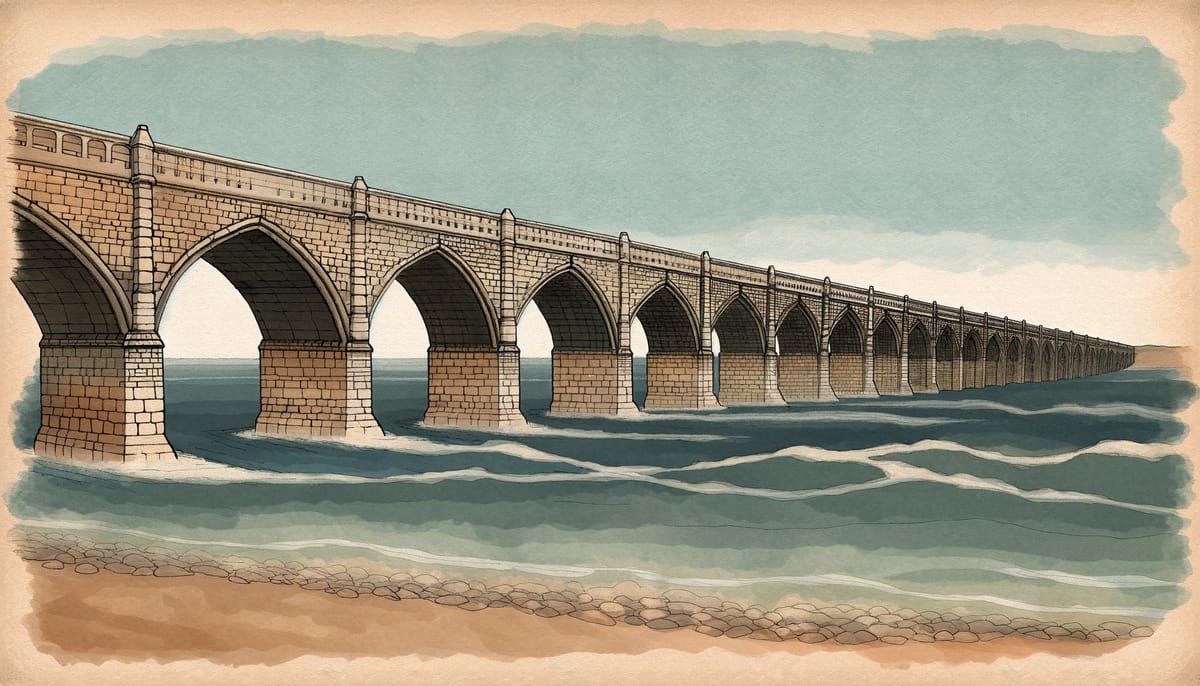

The Legal Architecture Beneath the Runway

The 2024 agreement emerged from a legal reckoning decades in the making. In 2019, the International Court of Justice ruled by 13-1 that Britain’s separation of the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius in 1965 violated international law. The decolonization process, the court found, “was not lawfully completed when Mauritius was granted independence in 1968.” The UK, it concluded, was “under an obligation to bring to an end its administration of the Chagos Archipelago as rapidly as possible.”

The opinion was advisory, not binding. But it carried weight. The UN General Assembly subsequently voted 116-6 demanding British withdrawal within six months. Britain ignored the deadline. Yet the legal pressure created a legitimacy deficit that complicated London’s position with every passing year.

For the United States, this created an uncomfortable dynamic. Washington had helped engineer the original separation, securing British agreement to establish the base in exchange for a discount on Polaris missiles. American diplomats knew the legal foundations were shaky. They also knew that defending a colonial-era territorial arrangement sat poorly with Washington’s rhetoric about a “rules-based international order.”

The 2024 agreement resolves this tension. Mauritius gains sovereignty. Britain gains a 99-year lease with renewal options. The United States gains legal legitimacy for a base it intends to operate indefinitely. The Chagossians—the indigenous population forcibly removed to make way for the military facility—gain the right to return to outer islands, though not to Diego Garcia itself.

What China Actually Gains

Critics of the sovereignty transfer warn that Mauritius might eventually evict American forces or invite Chinese ones. The scenario deserves examination.

Mauritius is a small island nation of 1.3 million people. Its economy depends heavily on tourism, financial services, and fishing. Its military consists of a coast guard and a few patrol vessels. The country has no capacity to project power and no history of confrontational foreign policy.

More importantly, Mauritius negotiated the agreement precisely because it wanted the lease payments and international legitimacy that come with resolving the sovereignty dispute—not because it wanted to host Chinese military facilities. The £3.4 billion financial package accompanying the deal creates strong incentives for Mauritius to maintain the arrangement.

Could a future Mauritian government change course? Theoretically. But the 99-year lease includes provisions for extension, and breaking it would forfeit substantial financial benefits while inviting American displeasure. Small nations rarely antagonize superpowers without compelling reasons.

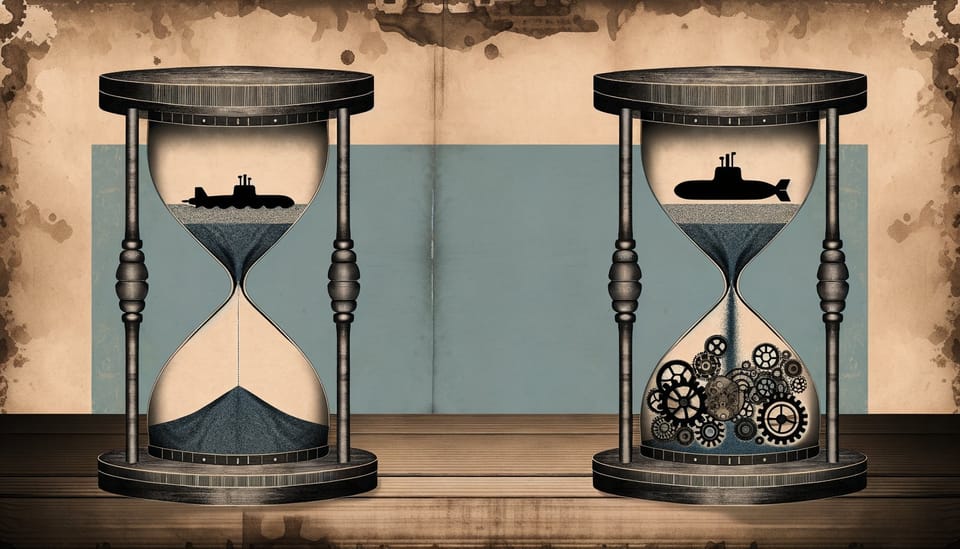

China’s Indian Ocean strategy, meanwhile, does not depend on acquiring Diego Garcia or its equivalent. Beijing has pursued a different model: commercial port investments that create access without sovereignty. Facilities at Gwadar in Pakistan, Hambantota in Sri Lanka, and Kyaukpyu in Myanmar give Chinese vessels potential resupply points across the ocean. The naval base at Djibouti—China’s only acknowledged overseas military facility—demonstrates that Beijing can establish presence without displacing existing powers.

This network approach offers advantages Diego Garcia cannot match. Chinese ships can access multiple ports under varying political arrangements. They face no single point of failure. The loss of any one facility inconveniences rather than cripples operations.

The comparison illuminates a deeper asymmetry. American strategy in the Indian Ocean depends on a small number of high-value fixed assets. Chinese strategy depends on a large number of lower-value distributed relationships. The sovereignty transfer does not change this structural difference. It merely highlights it.

The Redundancy Question

If Diego Garcia were destroyed tomorrow, what would the United States lose?

The honest answer: significant but not irreplaceable capability. B-52s could operate from bases in Australia, Guam, or—with aerial refueling—from the continental United States. Pre-positioned equipment ships could relocate to facilities in Singapore, Bahrain, or Darwin. Intelligence collection platforms could shift to other locations or to space-based systems.

The adjustments would be costly. Response times would lengthen. Logistics would grow more complex. Some operations that currently launch from Diego Garcia would become impractical. But the United States would retain the ability to project power into the Indian Ocean.

This is not speculation. American military planners have conducted exactly these assessments. The shift toward distributed operations reflects their conclusions: single points of failure are vulnerabilities, not strengths.

India’s growing naval capabilities add another dimension. New Delhi has invested heavily in indigenous technologies, including autonomous systems and maritime surveillance networks. Indian facilities at Port Blair in the Andaman Islands, at Karwar on the western coast, and at various points across the island chain provide potential alternatives or supplements to American basing.

The relationship remains complicated. India maintains strategic autonomy and avoids formal alliance commitments. But shared concerns about Chinese expansion have driven unprecedented cooperation. Joint exercises have expanded. Intelligence sharing has deepened. The possibility of American access to Indian facilities in crisis—while politically sensitive—is no longer unthinkable.

The Politics of Perception

The loudest opposition to the Chagos agreement came not from military planners but from politicians. The distinction matters.

For figures like Senator Rubio, Diego Garcia serves a symbolic function that transcends its operational role. The base represents American global reach, the ability to project power anywhere on earth. Ceding sovereignty—even while retaining operational control—suggests retreat. It feeds narratives of decline that resonate with domestic audiences primed to see weakness in any accommodation.

The Trump administration’s initial rejection of the agreement reflected this dynamic. “We will not give away our military base,” officials declared, framing the issue as territorial loss rather than legal regularization. The fact that the base would continue operating unchanged received less attention than the sovereignty transfer itself.

This creates a peculiar situation. The agreement strengthens America’s legal position while appearing to weaken its strategic one. The perception gap matters because it shapes political constraints on future decisions. An administration that accepts the Chagos deal faces accusations of appeasement. An administration that rejects it faces accusations of colonialism. Neither framing captures the operational reality.

The Thermodynamics of Basing

Military logistics follow patterns that resemble physical laws. Distance creates friction. Concentration creates vulnerability. Dispersion creates coordination costs. Every basing decision involves trade-offs among these forces.

Diego Garcia optimizes for reach at the cost of redundancy. Its central location minimizes transit times to multiple theaters. Its isolation minimizes political friction with host nations. But these advantages come with a single point of failure that modern precision weapons can exploit.

The shift toward distributed operations accepts greater coordination costs in exchange for greater resilience. Instead of one base doing everything, multiple smaller facilities each handle portions of the mission. The network degrades gracefully rather than failing catastrophically.

This transformation was underway before the Chagos agreement and will continue regardless of its outcome. The sovereignty transfer accelerates nothing. It merely occurs against a backdrop of strategic evolution that would proceed with or without it.

What Actually Changes

The practical effects of the agreement can be stated simply. Mauritius gains sovereignty and substantial payments. Britain resolves a legal embarrassment and maintains operational access. The United States continues using the base under the same arrangements that have governed it for decades. The Chagossians gain limited return rights that fall far short of their demands but exceed what they had.

China gains nothing it could not have obtained through other means. The Indian Ocean’s strategic geometry remains unchanged. American power projection capability remains intact.

What changes is the legal foundation beneath American presence. The base now rests on a negotiated lease rather than a contested colonial arrangement. This matters for legitimacy, for alliance relationships, and for America’s ability to criticize others’ territorial claims without obvious hypocrisy.

The critics who warn of strategic disaster misunderstand what Diego Garcia provides and what threatens it. The base’s value lies in geography, not sovereignty. Its vulnerabilities stem from military technology, not political arrangements. The agreement addresses the latter while leaving the former untouched.

FAQ: Key Questions Answered

Q: Will China be able to use Diego Garcia after the sovereignty transfer? A: No. The 99-year lease explicitly reserves the base for UK-US military operations. Mauritius has no authority to grant access to third parties, and the financial incentives strongly favor maintaining the current arrangement.

Q: Can Mauritius cancel the lease early? A: The agreement includes provisions making early termination extremely costly. Mauritius would forfeit substantial ongoing payments and face American diplomatic pressure. No Mauritian government has indicated interest in such action.

Q: What happens to the Chagossian people? A: The agreement permits Chagossian return to outer islands of the archipelago but not to Diego Garcia itself, where the military base occupies most usable land. A resettlement trust fund will support those who choose to return.

Q: Does this set a precedent for other US overseas bases? A: The Chagos situation was unique—a colonial-era territorial dispute with an ICJ ruling against British sovereignty. Most US bases operate under status-of-forces agreements with recognized governments, creating different legal dynamics.

The Long Game

Diego Garcia will remain an American military facility for the foreseeable future. Bombers will continue launching from its runway. Ships will continue sheltering in its lagoon. Intelligence analysts will continue monitoring communications across the Indian Ocean from its listening posts.

The sovereignty transfer changes the political frame around these activities without changing the activities themselves. This is not nothing—legal legitimacy matters for a power that claims to uphold international rules. But it is far less than the strategic catastrophe critics describe.

The real challenges to American power in the Indian Ocean come from elsewhere: from Chinese military modernization that threatens fixed bases, from alliance relationships that require constant maintenance, from the fiscal constraints that limit how much the United States can invest in distant facilities. The Chagos agreement addresses none of these challenges. It also creates none of them.

What it does is resolve a decades-old legal dispute in a way that preserves operational capability while acknowledging historical wrongs. In a world of difficult trade-offs, this counts as a reasonable outcome. The footprint of freedom remains. Only the paperwork has changed.

Sources & Further Reading

The analysis in this article draws on research and reporting from:

- UK-Mauritius Agreement on the Chagos Archipelago - Full text of the May 2025 treaty establishing sovereignty transfer and lease terms

- ICJ Advisory Opinion on Chagos - The 2019 International Court of Justice ruling on decolonization obligations

- UN General Assembly Resolution 73/295 - The 2019 resolution demanding British withdrawal

- House of Commons Library Briefing - Comprehensive analysis of the 2024 UK-Mauritius agreement

- Chatham House Analysis - Assessment of Diego Garcia’s strategic role and the Trump administration’s response

- BIOT Government History - Official account of the territory’s creation and administration

- ASIL Insights on Chagos - Legal analysis of the ICJ advisory opinion’s implications